Читать книгу Racial Immanence - Marissa K. López - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

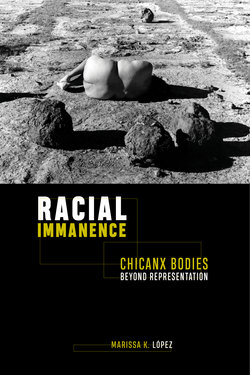

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Santa Anna’s Wooden Leg and Other Things about the Chicanx Body; or, What Are We Really Talking about When We Talk about Chicanx Literature?

You know, you have a lot of academics and you have a lot of politicians, and you have a lot of people sitting around saying, there’s no such thing as a Latino identity. And then … you look around and you’re like, “Nah that’s nonsense.” I think that I belong, and you all belong, to a moment when our community is knitting a larger identity in a really interesting and nuanced way. It completely escapes the politicians and the intellectuals.

—Junot Díaz

In conversation with hosts Felix Contreras and Jasmine Garsd on NPR’s music podcast alt.Latino, Junot Díaz, a Dominican American author, argues that despite diversities of class, race, and geography, there is still a tie that binds US Latinxs. That was not the case in the 1980s, he continues, when he was growing up listening to primarily English-language hip-hop. In 2016, Díaz marvels, his young goddaughters have plenty of Spanish-language music in their collections and feel free to embrace the salsa, merengue, and bachata upon which Díaz and his friends turned their backs in their youth.

For Díaz this is a sign of something that politicians and intellectuals cannot see, something that transcends market shares and voting blocs. To those, for example, who would argue that a Cuban American politician from Florida could never speak to the concerns of, let alone be embraced by, Chicanx activists in the Southwest, Díaz presents the language of music and the intangible filiations it conjures.1 There is something that unites us all, Díaz asserts, even though Latinxs come from many different places. But what is this thing that evades the intellectual’s grasp? What does nuanced knitting entail, and what is Díaz referring to when he talks about “identity”? What, most importantly, are the stakes of, and what role do the arts play in, pulling “identity” together?

These questions motivate Racial Immanence. In the following chapters I explore what it means to talk about Chicanx literature in a political and intellectual climate that minimizes at the same time it dangerously maximizes the value of human difference. Despite increasingly visible state violence against people of color as we move further into the twenty-first century, many still believe that the election of an African American president in 2008 heralded the dawn of a post-racial United States, a belief the US Supreme Court reinforced in Shelby County v. Holder (2013). “Our country has changed,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in the majority opinion for that case (Roberts).2 Critical theory has changed, too. Having confronted the internal contradictions of humanism, scholars now explore the posthuman. The planetary consciousness of the anthropocene, cyborgs, technoculture, and the formal utopias of object-oriented ontology are all philosophical domains where race, ethnicity, and inequality appear to have little purchase.

Alongside these political and intellectual attempts to render raced bodies invisible or insignificant, the number of Latinx bodies in the United States has been steadily increasing. In 2014 Latinxs accounted for 17.3 percent of the total US population, compared to just 6.5 percent in 1980 (Stepler and Brown). Latinxs are currently the largest minority group in the United States, and by 2060 the US Census Bureau expects Latinxs to make up 28.6 percent of the total US population (US Census Bureau). This population growth, moreover, has since the early 2000s been fueled more by US births than by immigration, inflammatory rhetoric notwithstanding. Latinxs are a constitutive and increasingly unavoidable segment of the US population, and they are overwhelmingly (63.9 percent) of Mexican origin (Stepler and Brown).

These statistics have, since the 1980s, motivated a range of projects—political, commercial, and intellectual—aimed at generating knowledge about this growing population. The data motivate me as well and illuminate my approach to untangling the questions raised by Díaz’s observations about Latinx identity and the stakes of Latinx cultural production. Data show both that there are many Latinxs in the United States and that our numbers will continue to grow. We must, therefore, pay attention to Latinx voices, and, comprising the significant majority they do, in the general population if not in academia, Chicanx voices can be taken as illustrative, if not exemplary, of broader Latinx trends.3 Beyond pure numbers, though, the historical, social, and political connections between the United States and Mexico condition twenty-first century latinidad. I am thinking here specifically of the militarization of the US-Mexico border, which I turn to in the fourth and final chapter of this book, and the structural impact it has had on what it means to be Latinx (not just Chicanx) in the United States, regardless of national origin. If for no other reason than this, it behooves us to attend to Chicanx voices in particular. But how can we listen if, as Díaz contends, Chicanxs and Latinxs are speaking at inaccessible frequencies? How do we—and why should we—attend to the invisible and the inaudible?

Problems

Our current strategies for reading literature by people of color do not directly answer this challenge. In The Social Imperative, for example, Paula Moya argues that textual analysis is key to racial understanding. In her introduction she describes being “challenged by faculty colleagues working in the social and natural sciences to demonstrate how literary criticism might contribute to an understanding of” race and gender, and even to explain “the value of literary criticism for the production of knowledge generally” (1). This she connects to a general sense of the humanities in crisis, especially in literary studies, where scholars struggle with increasing doubts that “literature or its criticism can provide the keys to our liberation” (5). In response to this crisis Moya proposes a return to basic principles, asserting the value of close reading “in the context of a changing American society in which literacy about race and ethnicity will be needed more than ever” (5). Close reading, she argues, is key to understanding how “race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality structure individual experience and identity,” and this, in her final analysis, is why it is important to read and study literature (6).

Moya believes that literature has ideological impact because close reading influences a reader’s perception of the worlds and peoples represented in a text. While scholars of Chicanx and Latinx literature may not all share Moya’s faith in close reading’s ability to promote “racial literacy” (6), they do tend to share her assumption that literature represents things in the world and that one of its primary functions is to communicate these things to readers.4 This is what I mean when I refer to “reading representationally” or “reading for representation,” and in Racial Immanence I argue that such an interpretive mode marks a division between reader and text that can preclude meaningful engagement.

While Moya asserts that race must be represented in order to be understood, Mel Chen argues the opposite. In Animacies, a study of the “alchemical magic of language,” Chen shows how language forms, hierarchizes, and coerces matter (23). “Words more than signify; they affect and effect,” writes Chen (54). Language, that is, does not just reflect the world; it makes, breaks, and shapes it. In a parallel theoretical vein, both Walter Benn Michaels and Jodi Melamed see representational reading as an impediment to social change. To read as Moya suggests performs a version of what Michaels in The Beauty of a Social Problem calls “neoliberal aesthetics,” which he defines as a way of looking that reduces art to its subject, to “hierarchies of vision” that occlude their underlying economic conditions (63). Melamed makes a similar argument in Represent and Destroy when she notes that “liberal terms of difference have depoliticized economic arrangements” by shifting the meaning of race away from material inequalities toward representational otherness (xvii). As Michaels links this to developments in aesthetic theory, Melamed similarly associates this formal anti-racism with literary multiculturalism as practiced in US universities that, she argues, destroys the potential of anti-racist knowledge (xi).

These pitfalls notwithstanding, I believe that we can attend to race without destroying it. To do so, however, we must reimagine the relationship between bodies, words, and the world. In any given moment of reading, texts are doing so much more than representing experiences, the appreciation of which will produce better, more empathic citizens. Reading for representation anticipates learning what we already think we know. By contrast, the works I bring together in Racial Immanence gesture rather than represent, and gestures, as Juana María Rodríguez reminds readers, “are where the literal and the figurative copulate” (4); gesture “highlights intentions, process, and practice over objectives and certainty” (Rodríguez 5). The bodies encountered in Racial Immanence gesture; they do not look, behave, or signify as anticipated. In these deviations they disrupt the temporality of expectation; they force a lingering that redefines politics as “something we await” rather than “something we arrive at,” to borrow Sandra Ruiz’s formulation (337).

In the following pages, for example, I read race as the unseen, unheard, and ineffable unifier that Díaz describes. The artifacts I explore are less interested, however, in the visible, external signs of race and more in the materiality of race as a physical condition of experience. My interest in matter continues a lively conversation around the multiple significances of race and ethnicity begun by Michael Omi and Howard Winant when they first published Racial Formation in the United States in 1986. As they make abundantly clear in their now classic and foundational study, race is both a process and product of modernity. It is, they assert, an idea, a “fundamental concept that has profoundly shaped, and continues to shape, the history, polity, economic structure, and culture of the United States” (106). In their third edition Omi and Winant admit that “the body was largely under theorized in our earlier accounts” (viii), but their more recent attempts to foreground the racial body rely on the ocular dimensions of race, on how the visual differences between bodies acquire social meaning through racial projects (109). While I concur with Omi and Winant that race is as pervasive and consequential as the air we breathe, I am not content to see bodies as passive and inert objects of racial formation. Omi and Winant understand bodies as “visually read and narrated in ways that draw upon an ensemble of symbolic meanings and associations” (111), but I prefer to grant the body and biology more active agency in the making of race.

For many years, though, and for good reason, scholars have operated under the assumption that race is not biological. It is a slippery slope from materiality to colonial eugenics, as Omi and Winant remind readers (24). To navigate that slipperiness, I take inspiration from Michael Hames-García, who wonders “what race might be beyond a means for oppression and exploitation” (331). Taking as a starting point the assumption that the body “is an agential reality with its own causal role in making meaning,” Hames-García explores the mutual constitution of biology and culture in order to argue a biological theory of race as a temporally variable phenomenon that emerges from the interplay of matter and socioeconomic forces (327). Likewise, I read the body not as a sign, or token, of subjectivity but as something more like the oscillation of current and voltage upon which, as Jane Bennett describes in Vibrant Matter, the US electrical grid is based (26). Race, in this analogy, is like the play of active and reactive power guiding the rhythms of current and voltage, intangible, but very, very real.

Omi and Winant, similarly, say that they “cannot dismiss race as a legitimate category of social analysis by simply stating that race is not real” (110). Race has real social consequences, they argue, even if it lacks a biological root; for them, race is both “located on the body” and “the means by which power is ‘made flesh’” (247). Like Omi and Winant, I see race as both noun and verb but understand it to be in rather than on the body. Race, this is to say, might not be locatable in the biological real, but it is nevertheless, I argue, a form of physical, affective experience that catalyzes personal and political change in the world. If race is merely an abstraction of geopolitical power, and the human body is a mutable, historically contingent phenomenon, then what, I ask in Racial Immanence, to make of the attention to disease, disability, abjection, and sense experience increasingly visible in Chicanx visual, verbal, and performing arts at the turn of the 1980s into the 1990s? What can this attention to physicality tell us about the real, political stakes of Latinx cultural production?

Answering questions like these demands a reading method that neither privileges nor essentializes the distinction between reader and text, that sees their imbrication and understands that Díaz’s “larger identity” is a red herring. Though it has received the most critical attention, identity is not what matters in Díaz’s Pulitzer Prize–winning tour de force The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007), which explores the history of the Dominican Republic through a science fiction–obsessed Dominican American protagonist. The titular Oscar is ni de allí ni de allá, from neither here nor there, steeped in US popular culture but living always in the shadow of his skin and the story of his mother’s country. Oscar’s identity is a distraction from the real matter of latinidad, which asserts itself less as a matter of content than of form.

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao suffers, charmingly, from a near total lack of nuance. It tells the reader exactly what to think of it, Oscar, and the Dominican Republic in didactic prose and with even more aggressive footnotes glossing the action and explaining the many historical and popular culture references. Even after the novel’s publication Díaz did not stop unpacking for his readership, annotating, for example, sections of the novel online.5 These notes enjoyed a warm reception in the popular and scholarly press, but they can be read as obfuscating just as much as they reveal. What if we thought about them as resisting, rather than inviting, interpretation?

Díaz’s footnotes in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao prioritize the act as much as the subject of writing, and on alt.Latino Díaz emphasizes the knitting as much as the knitted. His formulation shifts the focus of the conversation from object to action. This is the same move that political theorist Cristina Beltrán makes in The Trouble with Unity when she titles her conclusion “Latino Is a Verb.” People identified as Latinx, she writes, “do not represent a preexisting community just waiting to emerge from the shadows. Instead ‘Latino politics’ is best understood as a form of enactment, a democratic moment in which subjects create new patterns of commonality and contest unequal forms of power” (157). On the one hand, Beltrán sounds here like one of Díaz’s clueless intellectuals; on the other hand, her discussion of “enactment” as creating new modes of political community grants import to Díaz’s knitting and provides a new way of understanding his politics of form.

In Racial Immanence I attend to form as a mode of political action along the lines Beltrán describes. My primary vehicle for these explorations is the human body and the role it plays in Chicanx cultural production at the turn of the 1980s into the 1990s. Of course, artists attended to the body before the 1980s, but bodily meditations increase so significantly by the end of the twentieth century that, in addition to establishing a genealogy of corporeal musings, Racial Immanence asks what about this period prompts such marked attention to physicality in Chicanx arts. By theorizing Chicanx artists’ uses of the body, Racial Immanence makes a historical argument about how Chicanx cultural production responds to late twentieth-century neoliberal encroachments on the economic, political, and social lives of communities of color. In so doing, I also put forward different models for thinking through how “Chicanx” and “Latinx” signify in the twenty-first century and how these concepts can be socially and politically leveraged.

Abstractions

Interlude 1: The Leg

The Battle of San Juan de Ulúa began in the early morning hours of December 5, 1838, when the French navy landed 1,500 men on the shore at Veracruz. It led to a decisive French victory in the 1837–1838 “Pastry War” between France and Mexico.6 In the frenzy of the fight, General Antonio López de Santa Anna, commander of the Mexican forces at Veracruz, was severely wounded in his left leg with shrapnel from a cannonball that also killed his horse. The leg was amputated below the knee the next day and returned to Mexico City, where it was blessed with a Te Deum and buried (East, “Wooden Leg” 51). Some time after that, Santa Anna visited the New York City offices of Charles Bartlett, a prosthetics manufacturer, who built a custom-designed leg for the general (Carl Johnson 1).

It was a beautiful leg made of lightweight, easy-to-maneuver cork, and fitted with a swivel joint at the ankle to allow for natural range of motion (Carl Johnson 3). Santa Anna was surely sorry to lose it on April 18, 1847, when Samuel Rhoades, John Gill, and Abraham Waldron, members of the Fourth Illinois Infantry, stole it at the Battle of Cerro Gordo during the 1846–1848 US-Mexico War.7 The Fourth Infantry was assigned to attack Santa Anna’s troops, who held a key mountain pass blocking the US Army’s advance into Mexico City. Santa Anna escaped the surprise attack, but was forced to desert his carriage, which held, along with his leg, $18,000 in gold and a lunch of roast chicken. Upon discovery of the carriage, Rhoades, Gill, and Waldron ate the chicken, turned the gold over to their superior officers, and took the leg back to Illinois as a spoil of war.

Santa Anna’s amputated leg suffered the vagaries of his political misfortunes. After he lost political power, the leg was reportedly stolen from its tomb, dragged through city streets, and left at a garbage dump (East, “Cork Leg” 169). His prosthetic leg, however, remained in private, US hands for decades, enjoying adventures of its own. Its captors charged ten cents a head to view it in Illinois, but the leg also apparently traveled. Correspondence suggests that it was displayed in London’s Crystal Palace (East, “Cork Leg” 169) and news reports indicate that P. T. Barnum had it on view in his American Museum in the years immediately following the war (Harris 62). The State of Illinois gained possession in the early twentieth century, and the leg received little attention until 1942, when the state assembly passed a resolution to return the leg to Mexico. This much-protested resolution was never carried out. Instead, the leg was put into storage until 1974, when the Illinois National Guard included it in a mobile historical display that traveled to Washington, DC, in observance of the American Bicentennial (Carl Johnson 5). After that it was put on permanent display in the Illinois adjutant general’s office in Springfield, in which city visitors today can see Santa Anna’s wooden leg presented in a diorama replicating its scene of capture at the Illinois State Military Museum.

The story of Santa Anna’s wooden leg comprises most of the elements of my argument in Racial Immanence. The leg could be read as a parable of US-Mexico relations, but Mexico has its own conflicted relationship with Santa Anna and never launched an aggressive campaign for the leg’s repatriation. The leg on display in Illinois, moreover, is prosthetic, not flesh of Santa Anna’s flesh, and it was made in the United States. The Fourth Illinois Infantry captured a representation of a representation (figure I.1). P. T. Barnum presented America with a vision of its desire to possess a Mexico of its own manufacture, undermined by the ambiguous “nature” of the leg and the controversial character of the man to whom it was attached. The leg, therefore, cannot be read representationally. Let us consider it instead as an occasion to accept Hames-García’s invitation to think of race beyond subjection and disempowerment, to see the prosthetic limb as an unknowable illusion, a shade of human form that cannot be grasped, the circulation of which knits other objects together in ever-shifting patterns of the real.

A key question for me in Racial Immanence, then, is whether or not it is possible to think of race as something more than a human construct, to see Santa Anna’s leg as something other than a surrogate limb. What if, I wonder, inspired by the artists gathered within these pages, race is something real and material that nevertheless eludes language? Can we think of race without subjection? Can we imagine the body—can we imagine Santa Anna’s leg—not as indexing a racially managed subject but as an object among objects? How does Chicanx cultural production help us think of race as something that exceeds the individual, and what are the political and ethical implications of that imagining?

Figure I.1. A life-sized diorama at the Illinois State Military Museum in Springfield, of US soldiers capturing Mexican general Antonio López de Santa Anna’s wooden leg. Photo courtesy of the author.

To explore these questions, in writing Racial Immanence I have had to fight my own desire to interpret; I have instead forced myself to linger in the experience of reading to sense how chicanidad is not represented but produced in moments of textual engagement. Rather than make meaning, I have tried to honor texts’ resistance to interpretation. Modeling a transportable method, I have crafted readings as moments of what political scientist William Connolly theorizes as “emergent causality.” He defines this as “the dicey process by which new entities and processes periodically surge into being” (179). Doing this, I have responded to Antonio Viego’s call in Dead Subjects for revised notions of ethnic subjectivity that are “guided by the refusal of what we are currently made to be” (29).8 We should not, Viego argues, expect twenty-first-century Latinxs to act like or be guided by the behavior of historical Latinx subjects. He sees Latinx studies projects as motivated by a desire to root the future in a continuation of the past, a move that he says “drains the future into the past and burrows the past into the future” (22). Such historicist expectations produce, according to Viego, “dead subjects” unable to move forward in time, whereas he advocates for the flourishing of Latinx subjectivities that refuse to perform institutionally recognized latinidad.

Santa Anna’s leg, I contend, refuses to perform the drama of the US-Mexico border. Such refusals, I argue, are where the progressive potential of Chicanx and Latinx cultural production lies. Latinidad rests on a set of social expectations that must be upended if latinidad is to be anything other than an ethnic performance dictated by an Anglo-dominant majority.9 If, as Connolly argues, political change relies on intervening in how people perceive the world, rather than on changing what they perceive, latinidad must create moments of experiential dissonance wherein Latinxs refuse, in Viego’s words, “what we are currently made to be” (29).10 Viego finds that dissonance in Lacan’s refutation of ego psychology; for Cristina Beltrán, embodied political action is crucially dissonant; and Juana María Rodríguez reads queer gestures, either literal movements of the body or figurative manipulations of “how energy and matter flow in the world,” as dissonantly performative (4). Such moments disrupt the temporality of expectations; they render the future perennially surprising, impeding linearity and suspending time.11

That suspension can be the work of latinidad. Parallel efforts can also be made in Latinx studies if scholars create moments of intellectual dissonance wherein we refuse to look at and for that which our institutions have come to expect. Viego argues that “Latino,” a famously empty signifier eluding specific class and race distinctions, occupies a liminal time between a future knowledge and an always already knowing. “The temporal paradox,” explain Joshua Guzmán and Christina León, “collapses the demand for knowledge with an anticipation that forecloses any serious encounter with the object” (271). The now of latinidad is always already lost, constantly performing itself in the present moment of Anglo consumption, allowed neither past nor future.

Guzmán and León conjure “another ‘now’ for latinidad” (263) and in Racial Immanence I answer their summons to linger in the ambivalent present of latinidad, “to slow down the work of understanding latinidad and instead to dwell in the space of its many times and places” (272). To linger in the now of latinidad is to draw back from the desire to know and to turn toward the appreciation of an embodied present that does not necessarily point toward a future understanding. Lingering means embracing the future contingent as an emergent causality that halts the linear flow of an appreciation of the other that already knows what it wants to know.

Instead of learning what they already know, readers of Racial Immanence will witness the objects gathered herein fostering networks of connection that deepen human attachment to the material world. Readers will be challenged to think of text as a physical engagement and to see reading as a process of connection rather than interpretation. To consider reading as merging with the stuff of the world opens the door, as I explain more fully in my final chapter, to an ethics of shared vulnerability that reimagines the political.

Methods

Interlude 2: The Zine

In 2015 Maricón Collective, a group of queer artists and activists from East Los Angeles, produced a limited run of exact replicas of the first two issues of Joey Terrill’s Homeboy Beautiful. Maricón Collective were known as public historians who organized community-building dance parties with publicity materials featuring its members’ queer Chicanx art. They produced a zine of their own, but with the Homeboy Beautiful reissues, they paid homage to a pioneering queer Chicanx artist.

Terrill’s life, explains Richard T. Rodríguez, “represents a remarkable archive of Chicano, gay male cultural and political engagement consistently ignored or rendered nonexistent by revisionist scholars and activists” (467). Since the 1960s Terrill has performed politics through his art and activism, building, as Rodríguez describes, a “repertoire of interlocking lived, artistic, and activist practices” that made it possible to be queer and Latinx in the public sphere (467). Homeboy Beautiful, which Terrill printed and circulated in the late 1970s, was one such performance.

A tongue-in-cheek satire of popular women’s magazines, Homeboy Beautiful includes segments on fashion such as, in issue 2, “Leather for Homegirls” and a “Homeboy Makeover” in which a group of homeboys kidnap “Joseph Cornish,” an Anglo librarian, and make him over so he looks like a “native of Lincoln Heights.” Included are photos of a violent beating described as massages to Cornish’s back and neck with a two-by-four and “fancy footwork to ease away tension in the pec area.” There is an advice column, and, in issue 2, there are journalistic pieces like “Exposé: E.L.A. Terrorism,” in which Santo, an investigative journalist, embeds with a “radical homeboy terrorist group” engaged in “White-people kidnappings!!!!” In this photo essay the group kidnaps a couple from their home in West Los Angeles. The group finishes the couple’s board game before taking them back to East Los Angeles and forcing them to eat tortillas, chilies, and menudo. They are then made to watch Spanish-language television before the group leaves the couple dazed and confused on the streets of East Los Angeles.

The violent silliness of issue 2 culminates in the takeover of the Homeboy Beautiful editorial offices by the “homo-homeboy terrorists,” who put up political banners and spray-paint slogans across the walls. “We the Homo-Homeboys of Los Angeles,” they declare, will hold the Homeboy Beautiful editor hostage until “we feel that Homeboy Beautiful magazine sincerely attempts to represent the ‘ambiente’ of Homo-Homeboys in their publication.” Even as the zine pushes against Anglo-dominant representations of chicanidad—placing a newspaper clipping declaring, “In case you hadn’t heard, Chicanismo has come of age” next to an announcement, “Next Issue: Passing into White Society”—it recognizes intra-communal tensions over hetero- and homonormativity.

Even as it makes these explicit arguments about representation, the zine’s overall playfulness and convoluted narratives of undermined editorial control make it difficult to read as an argument for accurate reflections of a community. Even as it offers imagistic and textual windows onto queer Chicanx life, those words and images drip with a sarcasm that highlights representational struggles rather than represented objects. Homeboy Beautiful does not, in other words, represent queer chicanidad so much as it performs the struggle for survival and visibility. Maricón Collective’s exact copies of Terrill’s originals, by extension, do not so much assert a genealogy of queer chicanidad as argue that the struggle for visibility continues in the twenty-first century in terms not so different from Terrill’s in the 1970s.

Because Maricón Collective’s copies of Terrill’s zine do not use the past moment of Terrill’s production to anchor a progress narrative leading to their present-day Chicanx cultural expression, their twenty-first-century reissues of Homeboy Beautiful linger in an eternal now of queer chicanidad (figure I.2). The collective performs a perpetually self-ironizing struggle for visibility that anticipates never arriving at the moment of being seen. This refusal of linear time is also present in the content of the original zine; for instance, issue 2 opens with an editorial apology for its own lateness, refuses the coming of age of “Chicanismo,” has no formal indications of its date of issue save for references to California propositions 6 and 13, and characters in vignettes are usually late or pressed for time, operating—like the zine itself—beyond the bounds of temporal expectation.12 Homeboy Beautiful awaits itself, and Maricón Collective’s reissues are an iterative performance of a performance of lingering.

Figure I.2. Maricón Collective, Homeboy Beautiful cover (reissue 2), undated. Illustrator unknown. © Maricón Collective. Courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

As a genre, zines demand reading that lingers, that focuses on process over product, on representational strategies rather than represented objects. Zines, as Stephen Duncombe explains, are “noncommercial, nonprofessional, small-circulation magazines,” which their creators produce, publish, and distribute by themselves (6). They are products of passion that “communicate the range, however wide or narrow, that makes up the personal interests of the publisher” (Duncombe 10). Zines are a means without end; nonnarrative, noncommercial, they are modes of creative self-expression requiring, according to Todd Honma, neither technical skill nor adherence to any particular ideology or aesthetic. Zines are often thought of as individual endeavors, but they can be, as Honma argues, important community-building tools that promote a “participatory culture, in which everyone is encouraged to contribute according to their own capacities towards a shared collective experience.” Terrill’s Homeboy Beautiful and Maricón Collective’s reissues function both ways, as individual expression that is then cultivated, continued, and circulated by and through a collective of artists, activists, and community members.

To read Homeboy Beautiful as a work of Chicanx literature, then, demands considering the zine not as a representation of queer chicanidad but as both archive and actant of a particular social movement. This mode of reading must be nonrepresentational while also recognizing that Chicanx texts often have real stakes that matter in the real world. In Racial Immanence I limn this contradiction with a way of reading built around how racialized bodies flicker between indexical and materialist understandings of language. Homeboy Beautiful, to illustrate, hovers, with words and images, between meaning and mattering, yet the zine’s investments in race and gender linger. It remains socially and politically aware, that is, but refuses to clearly signify. That refusal makes sense only if we read in a way that brings both text and the human body into the fleshy folds of the stuff of the world.

I do this in Racial Immanence by mediating a philosophical argument between object-oriented ontology (OOO) and new materialism, whose disagreements open a radical space in which it is possible to read literature by people of color for things besides representation. OOO insists on the reality of things that can be neither known nor seen, but it flattens the work of language and prevents readers from achieving any great textual insight. New materialist theories of language, on the other hand, greatly expand our textual imaginations but offer no way to appreciate the significance of chicanidad. In this introduction I represent these fields in the work of Graham Harman and Karen Barad, respectively. From their points of tension and overlap I draw the building blocks of my own method.

A cornerstone of my approach is to insist on the reality of race despite its lack of genetic basis.13 Omi and Winant do this as well, but Harman’s work makes possible a consideration of race beyond the bounds of human sociality, and Barad offers the tools for keeping race rooted in the material world. Things exist whether or not we know about them, says Harman, rejecting the notion that things that cannot be thought do not, for all intents and purposes, exist. In fact, Harman writes, “the vast majority of relations in the universe do not involve human beings” (Immaterialism 6). If we thought of race as one such relation, it might be possible to read a Chicanx text, for example, for the ways it consciously resisted all attempts to “know” it instead of expecting it to teach readers something about Mexican Americans. Harman calls this “a weird [as opposed to naïve] realism” in which things actively resist interpretation (“Hammer” 187). Harman sees this as a form of what he calls “withdrawal,” a denial of substantive connection between words, things, and reality. This keeps him from seeing texts as active agents in the world, however, and leads to his substituting language games for textual analysis (“Hammer” 201).

Karen Barad, on the other hand, with whom Harman takes explicit issue (Immaterialism 14, 16), postulates “intra-action” over “interaction” as a way of understanding the relationship between words and entities. “Why,” she asks, “do we think that the existence of relations requires relata?” (130). What are the political and metaphysical stakes, she wonders, of dissolving the discrete boundaries around words? “Discursive practices are not … linguistic representations,” Barad contends, thus reimagining language as an agential intra-action catalyzing the emergence of matter into time-limited discursive practices (139). Barad rejects Harman’s distinction between ontology and epistemology, arguing that knowledge is gained not through observation but through embodied presence, by being in the world.

Drawing on both Barad and Harman, but mindful of their significant differences, in Racial Immanence I read in a mode best described as “choratic.” Doing so, I extend Rebekah Sheldon’s generative work on “chora,” which Plato describes in the Timaeus as both the place in which and the stuff from which a supreme craftsman formed the universe. “Chora’s” status as both space and stuff has long puzzled philosophers.14 Sheldon’s contribution to this conversation is to deploy “choratic reading” as a strategy for discussing the “emergent property” of matter that works “in the gaps between its actants” but “slips the noose” of language (Sheldon 209). This is, at bottom, what I mean to evoke with “racial immanence,” a method of reading choratically that emphasizes form as both the matter and energy of text.

“Racial immanence,” which receives a fuller explication in my first chapter, entails understanding race as animating the infolding of matter that coalesces into the cultural production at hand, as both constituting and being constituted by text. Reconceived in this way, language, human bodies, and all the matter of the world become intra-actional performances. Homeboy Beautiful appears as enacting political struggle rather than representing politicized subjects. Reading representationally stakes political claims built around subjectivity, rights, and human agency. What is the impact on reading, then, if we, as Guzmán, León, Beltrán, and Connolly do, pursue a radically different understanding of politics as affective moments of lingering and potentiality in productive tension? This brings me to the question I pose in my introduction’s subtitle: what are we talking about when we talk about Chicanx literature?

In Racial Immanence I treat texts as things rather than objects, not as things that represent other things, but as things in and of themselves. Homeboy Beautiful, for instance, forces a reading of itself as a thing that enacts and performs political struggle without resolution; it is an event that asks us to broaden the scope of actions that constitute “reading,” and it embodies the kinds of resistance to neoliberal aesthetics that runs as a thread through my chapters. To read it and the various other things gathered within these pages, I take as my methodological starting point Bruno Latour’s challenge in “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam?” to revivify criticism by shifting our attention away from matters of fact to matters of concern. “What if, ” Latour asks, “explanations resorting automatically to power, society, discourse had outlived their usefulness?” (229). What would it mean to read Chicanx literature, then, if not as verbally indexing the ways that oppressed social subjects experience power? Such a reading strategy requires thinking of literary texts not as reflective objects consumed by reflecting subjects, but as events in and of themselves that exist in and make the world.

I build readings that eschew a distinction between subjects and objects in favor of considering texts as “things” as Latour defines them: as either object, event, or place, as a “gathering” or an “issue” that launches a “multifarious inquiry” into the nature and motivations of a particular coming together. Homeboy Beautiful, to illustrate, does not represent actual queer Chicanxs from the 1970s. It deploys highly ironized stereotypes who sometimes appear in frame but sometimes, as in the case of “Homeboy Makeover” from issue 2, remain largely off-stage to indicate their status as figments of an Anglo-American imaginary. In the zine, queer Chicanx concerns linger in the province of text and drawing, awaiting their emergence into the photographic real, just as the broader queer political debates hover in the background of issue 2 as so many spray-painted slogans signaling a political future at which queer Chicanxs have not yet arrived and adumbrating a political present in which they are not fully seen. Their invisibility, though, is rendered not as disempowerment but as an effect of intra-communal struggles over the plurality of queer chicanidad reminiscent of Beltrán’s insistence on the impossibility of Latinx politics.

Homeboy Beautiful makes room for a queer Chicanx future that had not in 1978, and still has not as of this writing, arrived. In bringing the zine together with Santa Anna’s leg to introduce the things in my chapters, I aim to critique, as Latour suggests, not as “one who debunks, but as one who assembles” (“Critique” 246). The interludes in which I present the leg and the zine suspend the time of reading to invite reflection, to encourage looking without interpreting. I have avoided analyzing the leg and zine in favor of appreciating them as events, as flashpoints illuminating my methodology and gesturing toward the theories that ground it. These interludes also indicate how I am thinking about the human body in this book, as stuff existing in synergistic relation to other stuff, not bound by narrative constraints. This approach—critique by assemblage—proffers a way to think about Chicanx cultural production as doing something other than reflecting history or subjectivity. Approaching texts as events and bodies as confederations of things pushes us to think about what else Chicanx literature might be doing.

I write “something other than reflecting history,” but it is true that the literary texts at the core of Racial Immanence emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which also saw the consolidation of a “Hispanic” middle class in the United States and the promotion of the “Decade of the Hispanic.” This was a time of high visibility and increased rhetoric around Latinx concerns, but also a time of decreasing household incomes and heightened political antagonism (Stepler and Brown). In literary historical terms, this period corresponds with the emergence of queer mestizaje in the very influential writings of Cherríe Moraga, Gloria Anzaldúa, and others whose work depicts subjects in contradistinction to bourgeois white heteronormativity. While Anzaldúa does write extensively about the unruly body as a conduit for philosophical revisions of subjectivity—as I discuss in chapter 4—she remains most known, valued, and anthologized for the queer subject she ushered into print. In bringing together a very different set of texts from the same moment, by contrast, I propose another way of characterizing this period of Chicanx literary history. The authors in Racial Immanence respond to the corporate consolidation of “Hispanic” identities not by asserting counter-subjectivities but by undermining representation and visibility as political and aesthetic strategies.

Praxis

I tease out this undermining in my readings by connecting textual bodies to a series of extralinguistic objects. Though the literary works I discuss were produced mainly in the 1980s and 1990s, the material objects in my study trace a chronological sweep from fifteenth-century Aztec stone carvings to twenty-first-century Chicanx punk rocker Álvaro del Norte’s accordion. My argument in Racial Immanence works both chronologically and by accretion, simultaneously providing and interrupting a temporal structure by unfolding a specific historical period into interlocking moments of lingering. First, I trace a microhistory of racialized objects, beginning with the central premise that objects always resist, in one way or another, the desire to own them. Though this looks different at different points in time, from it can be extrapolated an enduring truth about our inability to know “things.”

I follow this idea through a series of accretive chapters that reimagine political community and the work of reading and writing. Communities comprise bodies, and Racial Immanence is about how bodies create choratic networks that are both in and of the world. In each chapter the body is an occasion to linger, and in these moments the intersections of race with time, visuality, the planet, and the extraterrestrial are figured anew. Attending to the machinations of the body, I argue across my readings, posits the body as a portal through which the imbrications of the political and the aesthetic can be reconceived. In this I have been inspired by Stacy Alaimo’s germinal work on transcorporeality, her neologism for the ways “the human is always intermeshed with the more-than-human world” (Bodily Natures 2). I turn to Alaimo most explicitly in chapter 3’s discussion of AIDS and the Latinx political imaginary, but her influence is apparent across the entirety of this book.

Chapter 1 takes up the work of Dagoberto Gilb and the compromised bodies that inhabit his fiction. Here I am interested in the relationship between sensation and language in Gilb’s work and how bodies produce their own temporality, their own lingering moments during which race becomes an immanent condition of his protagonists’ experience of time. I frame my analysis with a discussion of the discovery in 1790 of the Aztec calendar stone in Mexico City. There is no clear anthropological consensus on the purpose or meaning of the stone’s markings, which convey time as well as events of geologic, religious, and political significance. In its fusing of time and space, the stone allows me to present temporality and materiality as intertwined and race as the chora from which these concepts issue in Gilb’s fiction.

These ideas ground my explorations of the body in the remaining three chapters. In chapter 2 I postulate the body as mediator of form as well as stuff. Reading Cecile Pineda’s novel Face (1985) together with contemporary art and commercial photography, I argue that the body is both form itself and a thing through which form passes; it mediates between forms by being both the subject and the structure of the photographs in the novel and the photo projects I read alongside Face. In addition to choratically mediating things and forms, the body marks a crisis of signification in my reading of Chicanx AIDS fiction in chapter 3. There, my framing object is barbasco, the wild Mexican yam from which synthetic hormones were first derived, thus enabling the development of, among other things, oral contraceptives. In addition to interrupting the linear time of heterosexual reproduction, barbasco’s size, root structure, and resistance to commercial cultivation occasion a rethinking of indigeneity and global markets. I use this reimagined indigeneity as a lens through which to read Gil Cuadros’s and Sheila Ortiz Taylor’s depictions of the body as mediating sex, death, and the roots of culture in City of God (1994) and Coachella (1998) respectively.

Chapter 4, finally, moves from Cuadros’s and Taylor’s earthly concerns to ponder the body’s mediation of technology and the extraterrestrial. Using the work of contemporary Mexican digital installation artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s idea of “participation platforms” to ground my reading of two Chicanx science fiction novels—Alejandro Morales’s The Rag Doll Plagues (1992) and Lunar Braceros, by Rosaura Sánchez and Beatrice Pita (2009)—in chapter 4 I explore how bodies interact with and mediate geographic, planetary, and political spaces. In chapter 3 I consider what it means to ground the body in specific places or to depict bodies as being out of place, but the novels in chapter 4 inspire an exploration of what it means for the body to both physically constitute and be physically constituted by space.

Situating the body as an object among objects, my chapters create a material archive, a network through which to reimagine the racialized body. Each chapter advances a way of reading the body in relation to different epistemes—time, form, planetary consciousness, and bio- and cyber-technology—that bring us back to at the same time they appear to move us away from racial considerations. I offer, within these pages, a way of reading that sees the body as doing something other than representing a set of racialized experiences. Santa Anna’s wooden leg may be directly tied to the experiences of a specific community, but racial immanence and the ways of reading that it makes possible are transportable.

To illustrate that claim, and by way of closing, I turn to King of the Hill, the animated series about the Hill family, their friends, and their adventures in the fictional town of Arlen, Texas, which ran on the Fox network from 1997 to 2009. “The Final Shinsult,” the thirtieth episode of King of the Hill, aired on March 15, 1998, just a few years after the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994.15 In “The Final Shinsult,” Santa Anna’s leg is making a cross-country tour of the United States before being returned to Mexico, and Arlen will be its last stop. Bobby Hill’s middle school is performing a play about the leg and planning a field trip to visit it at the Arlen Museum. Bobby’s father, Hank, convinces his own father, Cotton, to help chaperone the trip. Cotton, who has recently failed an eye exam to renew his driver’s license, is thrown into even more of a rage when he learns of the leg. “You see, Bobby,” he yells, “your daddy’s generation is giving away everything we fought for!” The “Shinsult” of the episode’s title refers to Cotton’s anger about the leg as well as the ongoing humor the series finds in Cotton’s diminutive stature. “A man who gave his shins to win the Second World War,” explains Hank’s friend Dale, “has earned the right to drive an automobile.”

Later in the episode, the museum director stops the school bus as it is leaving and accuses the children of having stolen the now-missing leg. Hank heaves a beleaguered sigh and tells the children that he will now close his eyes and wants to see the leg when he opens them. He turns his head and opens his eyes to gaze into the distance, where he sees Dale and Cotton sneaking away from the museum. Cotton has Santa Anna’s leg strapped to one of his own, the other is strapped to Dale’s, and the two men hobble toward Dale’s car as if competing in a three-legged race. When Hank later confronts them, Cotton and Dale refuse to tell Hank where the leg is, revealing, after Hank leaves, the leg’s hiding place on a makeshift altar in a broom closet, sporting a fuzzy pink slipper, surrounded by holiday lights and empty beer bottles.

When the police finally come for the leg, Cotton tells them, as he resists arrest, “I need that leg for leverage in my negotiations with the Mexican government!” The leg is, however, eventually returned to Mexico in a ceremony at the Arlen Museum. City officials formally hand the leg to a retired Mexican army captain who, like Santa Anna, is missing a leg. “When he straps on Santa Anna’s leg and walks it from our flag to his it will be officially returned to the Mexican people,” Bobby’s mother, Peggy, tells him. The captain straps on his leg and begins to walk, but before he can reach the Mexican flag the leg shatters under his weight. “Hey, wait a minute,” says Bobby’s friend Joseph. “That’s the leg I made for the play.” The episode closes with Cotton in Mexico exchanging the original leg for a driver’s license.

We can read “The Final Shinsult” as exemplifying how Santa Anna’s leg continues to resonate as a sign of NAFTA-induced economic anxiety, the giving away to Mexico of everything the United States feels it has rightfully earned. We can also see the leg in this episode as the objective correlative of national desire. As Cotton’s body fails him, his investment in the Mexican prosthesis increases, with the result that his desire for the leg tells us more about his own feelings of inadequacy than it does about US-Mexico relations. Such insights are not novel, nor do they employ novel methods. I offer these analytic options as a call to reconsider the work of reading.

In King of the Hill Santa Anna’s wooden leg gestures toward the collective frailty from which grounds a new political imaginary might emerge. Joseph’s papier-mâché leg cannot support the political theater of international relations surrounding its return. A different kind of theater surrounds the original leg, however. Dale and Cotton’s altar is a performance of devotion demanding embodied, cooperative action that remains off camera. We do not see them building it together, but the way they clink their cocktail glasses together as they look at the altar suggests that it was a joint effort. The original leg binds characters to each other, draws them into a web of historical and physical concerns. In a moment of comic relief, the leg physically unites Dale and Cotton as their bodies stumble awkwardly as one. Similarly, the idea of the leg unites Cotton with the Mexican captain at the ceremony in Arlen, and both men are connected—across time, space, and national borders—with Santa Anna. At the same time, the episode flatly refuses maudlin readings of disability by depicting the leg as a token of material exchange that allows Cotton to finally get his driver’s license, thus achieving his longed-for freedom and mobility.

Desire is tricky, though, and how can we ever really be sure what Cotton longs for? “The Final Shinsult” reminds us that if we are reading to learn about the other, we are reading, most likely, to learn what we already think we know, to see what we want to see. What, then, does Santa Anna’s leg mean? That, at the end of the day, is not a particularly useful question. Whether in P. T. Barnum’s circus or on King of the Hill, representations of the leg will tell us about their representative moments, not the leg itself. And yet, there is still a leg there. An encounter with the leg produces a certain kind of affective experience with Chicanx resonance. What can we say about that experience? About the leg? Why do they matter?

These are the questions I grapple with in Racial Immanence. This book is a critique of representational reading and a searching out of other ways to think about the value of race and ethnicity in the arts. Within these pages, race becomes immanent and speculative, a historical node or catalyzing agent of the different trajectories my objects trace. The corporeal in Racial Immanence becomes transcorporeal; the human body becomes not a metaphor for subjectivity, but a way to articulate a philosophy of transformative and leveling interconnection.