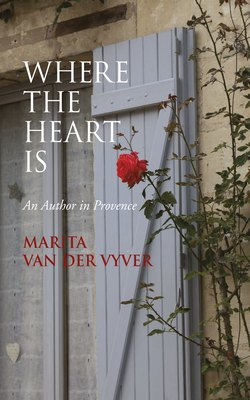

Читать книгу Where the heart is - Marita van der Vyver - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5 Marry at leisure

Оглавление‘Shouldn’t we just get married?’ Alain asked one afternoon when I once again lay crying in a miserable bundle on the bed. ‘It will at least solve a few of your problems with the bureaucracy.’

Not exactly what you’d call a romantic proposal, is it?

But at this stage nothing in my life was exactly romantic. I was living in the loveliest Provençal landscape, but I was so vehemently battling the French bureaucracy that I scarcely noticed the landscape. I was still hunting for official papers, and like any hunter worth his salt I had my eye on the prey rather than the scenery.

‘It won’t help,’ I sobbed with red eyes and a wet nose. ‘They won’t give me a driver’s licence just because I’m married to someone who has a driver’s licence.’

For that was what this afternoon’s crying bout was all about.

Well, actually it was about more than a driver’s licence. Let’s call it a cultural problem. National legislation leading to international misunderstandings. All symbolised by that shred of paper you need to drive a car.

I needed an insurance policy for the 15-year-old Golf I’d recently bought from a neighbour. The insurance company wasn’t satisfied with the temporary international driver’s licence I’d managed with until now. If I wanted to insure the rusty little car with its torn seats, I needed a French driver’s licence. But with this new French driver’s licence I’d have to pay exorbitant monthly premiums on the policy – because as a ‘new’ driver I’d be considered a danger on the road.

I therefore had to prove that I’d been a responsible driver for two decades. All I needed was a photocopy of my twenty-year-old South African driver’s licence. Did I say all? In the New South Africa the new government had just introduced a new system of driver’s licences in the form of laminated cards. Therefore my South African driver’s licence was also brand-new.

My previous driver’s licence was, alas, in my previous identity document. This identity document had been replaced the previous year with the new identity document for which everyone in the New South Africa had to apply. In short, I had no proof that I’d been driving for years on some of the most dangerous roads in the world.

Of course I couldn’t blame the French for the new laws of my fatherland. I’d simply have to put up and pay up.

But I did blame the French for refusing to issue my French driver’s licence unless I relinquished my (brand-new! expensive!) South African driver’s licence. I have to travel to South Africa regularly, sometimes at short notice, and over there I need a local driver’s licence. The alternative, which is to apply for an international driver’s licence every time I travel to South Africa, is too awful to contemplate. Here in France it’s not a matter of quickly popping into the nearest AA office and walking out with your international driver’s licence. Here you have to complete forms, as for anything you want to do here except go to the toilet (and for all I know you’ll soon have to start completing forms for that), and then you have to wait. Sometimes for months on end.

It was this checkmate situation that made me sob my heart out that afternoon. And all it produced was a marriage proposal.

Of course it wasn’t the first time that the word ‘marry’ had come up in our conversation. I’d moved to France boots and all because I was crazy about this man, but I’d resolved to get all my official papers in order, and only then we’d talk about marriage or no marriage. Just in case the man might think I was marrying him to make the paper trail easier.

But how was I to know that the paper trail would continue for more than two years? Or that in the meantime we would have a baby girl who would be crawling all over the house when I was still crawling around in front of French officials trying to get my hands on yet another essential document? To be completely honest, by now I didn’t mind quite so much that my husband might one day reproach me because my reasons for marriage hadn’t been entirely noble. I was beginning to think that I might be able to live with such a reproach.

And then my brother came to visit and Alain and I looked at each other and said, pourquoi pas? Why not pop over to the mairie and ask the mayor to marry us? Then at least I’d have a relative from South Africa as witness to the event.

Maybe I’d gone temporarily insane. Maybe I was imagining that I was living in Las Vegas where you could marry just like that, on the spur of the moment. Surely I should’ve known that no official transaction could be so effortless in this part of the world.

If I’d known how difficult it would be to arrange a simple wedding at the mairie – just the bridal pair and their children, I foolishly thought, just the briefest little ceremony imaginable – then I’d bloody well have remained unmarried.

Does anyone still remember the terrifying slogan for the movie Jaws II? Just when you thought it was safe to go back into the water … Indeed, just when I thought that it was safe to live in France, that there couldn’t possibly be an official document left to complete, I decided to get married.

Then I was exposed to a new torrent of forms and papers.

One of the many requirements was a complete birth certificate – requested from Pretoria and translated into French by an official translator – with a date stamp less than three months old. Sound familiar? Don’t forget that I’d been on this absurd merry-go-round before when I had to prove that I was my own child’s mother. By now I knew that it took three months to get your hands on such a certificate.

By which time my brother would have been back home, his French visit little more than a memory.

And if by some miracle the certificate arrived before the three-month deadline, we’d have to get married straightaway – no time to invite friends or family from afar – or we’d have to apply for the certificate again. And again hope in vain that it would reach us within three months. And again …

In the end we asked a family friend in Pretoria to collect the certificate in person and send it by express delivery, and so gained a week or three. But we were still rushing around to collect the rest of the papers.

As a prospective bride from a foreign country I needed, for example, to hand in a doctor’s certificate at the mairie. The prospective groom wasn’t expected to visit a doctor. It made no sense to me. Why? I wanted to know. Remember, by now I’d already given birth on French soil, and before I could do that, I was tested for every possible and impossible disease and complaint. The French really can be overly efficient when it comes to health.

But if I was found to be suffering from some mysterious condition that hadn’t emerged during all those prenatal medical examinations, I asked Nathalie of the mairie – could the mayor refuse to marry me? Not as far as she knew, Nathalie said with her usual Gallic shrug. So what was the use of such a doctor’s certificate? She wouldn’t know, Nathalie said, she was just doing her job. Look, there it was on the official form, at the bottom of the extensive list of required documents: All foreign women under the age of 50 who want to marry in France have to submit a medical certificate.

Maybe it’ll be easier to wait until you’re fifty before you marry, was my brother’s laconic comment.

I would be fifty anyway by the time I’d assembled the entire stack of papers, was how it seemed to me.

And when at last we walked into the mairie, triumphantly, with a plastic bag full of papers to set a date for the wedding, Nathalie’s face fell as if she had to give us news of someone’s death. The mayor wouldn’t be able to marry us the coming Saturday. Or the next one. Nor probably on the Saturday after that. It was harvest time, you see, les vendanges as they call it in this wine region, and the mayor wasn’t just the mayor. He was also the owner of a vineyard. And of the village’s only wine

cellar.

Les vendanges is something to experience in the French countryside. Because most of the farmers don’t have permanent workers helping on their farms, every available body has to pitch in during the harvest. This means all the housewives in the village, all the unemployed men in the area, the adolescent children, the nephews and nieces. Even the barflies like Jean-Pierre tear themselves away from the bar counter for the sake of this communal task. (Not entirely without self-interest, since they’re going to be drinking quite a lot of the wine that will be pressed from these grapes.) Hakima sends word that for a week or three she won’t be able to come help in our house because she must help in the vineyard. (Unlike the barflies, she’s doing it for purely economic reasons. Her Muslim family are about the only people in the village who don’t drink wine.) Until a few years ago even Madame Voisine did her share – although she’s so frail that you wonder how she ever managed to lift a basket of grapes. She was driven by neither economic reasons nor intemperance. She just did it out of curiosity. Now that she’s too old to stand crouched all day long, she misses out on the juicy stories that are spread so literally through the grapevine.

Seasonal workers appear from every direction overnight. Large families from Spain and the poorer East European countries, dark wandering gypsies and bored university students from the cities, Rastafarians and backpackers, Algerians and other North Africans. The green vineyards instantly turn into a kind of United Nations, a confusion of tongues from the crack of dawn till the sun sets, for seven days a week, until the last bunch has been picked. And then, just as suddenly as the Babylonian business began, it’s over. You wake up one morning to find all the seasonal workers gone, the housewives back in their houses, Jean-Pierre back in the bar, and the vineyards empty and still.

Until next year.

I like the vendanges. I even feel a little melancholic every year when it ends. But it isn’t a good idea to get married during the harvest – especially not if your mayor is a wine farmer. Even if you managed with some effort to convince him to take a one-hour break from the vineyard, there’s still the risk that the official witnesses to your wedding ceremony won’t arrive on time. Their car will probably be delayed by the rows of tractors on their way to the cellars with their wagonloads of grapes.

Our witnesses, two of Alain’s colleagues, arrived so late that we almost had to cancel the wedding. Our mayor, short and round with a pair of wild black eyebrows and a head of black hair standing permanently upright as if he’s just been electrocuted, walked up and down impatiently and kept frowning at his watch. There were still a lot of grapes to be picked that day.

And because France is France, we couldn’t simply ask two other friends (our only guests aside from our children) to take over the role of official witnesses. Among the many forms we had to complete beforehand, there were two for all the information about our witnesses that you could think of: full names, where and when and why they had been born, that sort of thing. In other words: if your witnesses don’t arrive, you might as well go home to change out of your wedding dress and start filling in forms again for permission to get married on another Saturday.

In our case that would definitely have been after the harvest.

The main reason why the mayor did after all agree to marry us on this inconvenient Saturday in September was that, for the first time in years, possibly decades, there had been two requests for wedding ceremonies. The other couple were, just like my less-than-radiant groom and me, not exactly spring chickens either. It was also a second wedding for them both and they also came to be wed in the presence of their children. The only difference was that they had more guests than children.

And oh yes, the other bride also looked decidedly more bridal than I did. She arrived in a smart hat, with a beautiful bouquet and a professionally made-up face. I was still feeding the baby half an hour before the wedding, with a dishcloth tied around my neck to keep my ‘wedding gown’ more or less clean. I’d bought the dress at a flea market a few days before – after briefly considering wearing the magnificent silk creation in which I’d embarked on my first marriage more than a decade earlier.

Like many inexperienced brides (you know better the second time round), I’d hung my designer wedding dress in a wardrobe years before in Cape Town, in the vague hope that it might one day enjoy another existence as an elegant evening gown. The problem was that I was never really invited to the kind of glamorous events where you’d need an elegant evening dress. A few literary award ceremonies were more or less the highlights of my social calendar, and a writer doesn’t want to look like a bride when she’s receiving a literary prize. Or worse, when she’s not receiving the prize. So the wedding dress stayed in the wardrobe year after year.

When I moved to France, the wedding dress came along, partly for sentimental reasons, partly because I thought that it might finally be revived in another country, where no one knew my wedding dress or me. Alas, in the French countryside my social life was even more limited than in Cape Town. And after my daughter was born it disappeared completely. My second wedding therefore seemed like the very last chance I’d ever have to wear my beautiful wedding gown. Although I shuddered in advance at what any guide to etiquette would say of a bride who got married in the same dress twice.

And yet I knew from the start that it wouldn’t work. You couldn’t wear such an immodest dress to such a modest wedding. And I was determined that the wedding would be modest. My first marriage had begun with an impressive dress and ended with an impressive lawyer’s bill. This time I would do it differently.

Besides, the groom didn’t even own a tie, let alone a smart suit or a pair of suitable shoes.

However, my brother decided to lend his new brother-in-law a suit and, as my brother is also not really the suit-wearing type, it was a fairly flamboyant one with a collar of black brocade and a lining of scarlet satin, something that dated from London’s Carnaby Street in the sixties. Such a wedding suit encouraged the groom’s sense of the theatrical, and underneath the red satin lining he wore the frilly shirt he’d worn in an amateur theatre production a few months earlier.

It was therefore one of those rare weddings where the bride’s outfit drew less attention than the groom’s.

And because it was such a historical day for our little village, the local correspondent for the newspaper La Provence came to take our picture, which was published the following week under the headline, ‘Two in one day’. The other couple’s picture didn’t appear along with ours, which unfortunately created the impression that Alain had married two women in one day. It led to many jokes in the local bar, particularly as we were surrounded in the picture by a crowd of children that couldn’t possibly all belong to one woman. Besides the four children which Alain and I had brought into the world separately and together, there were also the two children of our official witnesses, plus a few of the village children who happened to be hanging around outside the mairie (probably because their mothers were all picking grapes), and who posed with us uninvited.

It certainly didn’t resemble a traditional wedding picture, more like a children’s choir with their two tired middle-aged chaperones.

I didn’t mind. All that mattered was that all those months of filling out forms and signing papers were finally over.

Or that’s what I thought. Soon afterwards we decided to buy a house. And then the paper chase started all over again …