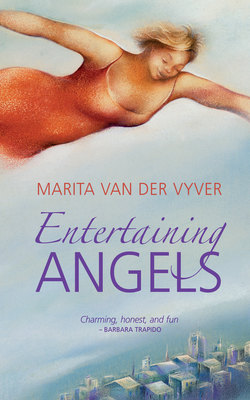

Читать книгу Entertaining Angels - Marita van der Vyver - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6

ОглавлениеI’ll Huff and I’ll Puff and I’ll Blow Your House Down

Griet felt like crying when she saw the house she’d lived in for so many years. Home is where the heart is, she thought as she walked through the neglected garden. And if you no longer have a heart, home is probably where your books and your music and your most precious memories are kept.

The clivias burned like orange flames under the bedroom window. A powerful antidote to impotence, according to old wives’ tales, and protection against evil. Although a small forest of clivias couldn’t protect the inhabitants of this house from impotence or evil.

She unlocked the front door carefully, and felt her knees weaken as she stepped inside. She could smell her husband, she realised in a panic in the hallway, next to the table with the telephone and the answering machine. But he couldn’t be here. She’d made certain that he wouldn’t be here. It was only his smell lingering in the house: the smell of his toasted cigarettes and his body after a game of tennis and the red soap he used every morning in the shower. She could smell him because the memories in this house sharpened all her senses, because she had crept back like a dog to dig up old bones.

Grandma Hannie’s house was a House of the Senses, a small labourer’s cottage on a Karoo farm, cool and dark as a cellar, especially on Sunday afternoons when everyone was supposed to be sleeping. There was a front door used by nobody but the dominee, and a back door that stood open day and night with a screen door that slap-slapped continually. One hard slap, deafening until you grew accustomed to it, and two softer slaps like echoes, every time someone came in or went out of the kitchen.

There were a number of other noises around the house, especially on a hot Sunday afternoon. The crack of the dog’s jaw as he snapped at flies, the complaints of the windmill in a sudden gust, the drone of a lorry far, far away on the highway. The creak of Grandpa Big Petrus’s bed when he rolled his giant frame over.

And at night there were inexplicable gurgling noises in the attic. Grandma Hannie said it was rats or something; Grandpa Big Petrus said: Impossible, rats don’t gurgle, it was Something. Grandma Hannie shook her head and held her peace.

The most memorable sound was the hymn they sang in their bedroom at dawn each day, after they’d read a passage from the Bible and said a few prayers. Grandpa Big Petrus’s confidently pure bass, followed by Grandma Hannie’s hesitant falsetto. She didn’t care much for singing, she only did it to make him happy.

Griet looked through the pile of unopened mail on the telephone table, found a few envelopes addressed to her, mostly accounts that she thrust into her handbag and Reader’s Digest Sweepstakes which she crumpled up. She went to the kitchen to throw them away. Really just an excuse to postpone braving the bedroom.

She’d left in a hurry, just throwing a toothbrush and a few items of clothing into a suitcase in the middle of the night after her husband had told her she was the most pathetic specimen of humanity he’d ever come across. She’d spent the rest of the night sitting in her car down at the beach, feeling just as pathetic as her husband said she was. At five the next morning she’d gone to her office – the security guard in the entrance foyer stared at her creased clothes and uncombed hair – and rung Louise in London.

‘I need your flat for a couple of weeks, until I find a place of my own.’

‘What’s wrong?’ Louise mumbled drowsily – it was still dead of night in London. ‘What’s going on?’

‘George has thrown me out.’

She tried to sound businesslike, not to saddle Louise with her personal problems, but her voice wouldn’t co-operate. The night in the car had been unreal, a nightmare she’d wake from, but now she was awake: she didn’t have a fairy godmother, she told herself in front of her word processor in the grey morning light. She couldn’t think of anyone able to turn a pumpkin into a flat.

‘Shit.’ Louise’s usual response to any communication out of the ordinary. After a long moment of silence during which Griet expected the dreaded ‘I told you so’, Louise sighed dramatically, ‘Marriage stinks, that’s all I can say.’

‘Can I use your flat, please, Louise?’

Her voice was trembling dangerously.

‘Of course.’ Louise was wide awake now. ‘Stay as long as you like but don’t be surprised if I join you in a couple of months. My husband’s driving me up the wall.’

Louise had married a British citizen because she wanted to get rid of her South African passport – as she admitted unblushingly – but she was sceptical enough about the arrangement to hang on to her Cape Town flat. You never know, she said. It’s best to keep the back door open. She’d learnt her lesson with her first divorce. Griet thought her friend was far too cynical to make any marriage work.

‘Is it that bad?’

‘It’s like being married to the Pope. And not being able to tell him he doesn’t have any clothes on.’

‘That was the emperor.’

‘No, the fucking Pope! It’s the righteousness that gets me down, the holier-than-thou attitude that Brits like him are apparently born with. He won’t even fart in front of me. As though only we barbarians from Africa have such basic needs. But when he’s in the shower, he farts so loudly I can hear him in the living room.’

‘Where’s he now?’

‘Don’t worry, he still doesn’t understand a word of Afrikaans. Anyway, I just wanted to let you know that you’re not alone in the struggle. Marriage is a great institution, as they say, but who wants to live in a fucking institution?’

Despondent, Griet got up from the phone and again passed the confused security guard. It was going to be a miserable day, she thought while her car lights sliced through the wisps of mist that hung low over the quiet streets. Welcome to reality, Louise had said.

And now, three months later, she was still in limbo. Alone in a strange flat with a kitchen full of cockroaches.

When other people split, she thought as she squirted the hole in the ozone layer bigger and bigger in her Struggle against the cockroaches, the man is normally the one who moves out of the house.

The woman is, after all, the one who looks after the house, she thought resentfully, who’s responsible for everything from the colour contrast of the living room cushions to the choice of toilet paper. Not always because she wants to be responsible for everything. Sometimes she’s just too tired to make a feminist last stand in front of the stove. Anyway, Griet acknowledged bitterly, it’s humiliating to wipe your bum with newspaper while you and your husband argue about Germaine Greer and Gloria Steinem. In the end it’s less trouble simply to go out and buy the toilet paper yourself.

But everyone knows it’s easier for a man to live out of a suitcase. What do you do if you begin menstruating in the middle of the night and you discover you didn’t pack your Lil-lets? Or if you forget your imported nightcream and you don’t have enough money to buy another jar, and every morning when you face a borrowed mirror you have to stare in horror at the new wrinkles that have formed round your eyes overnight?

What is a house without a woman? Griet wondered as she walked through her house for the first time in weeks. What is a woman without a house? What is a woman without her husband’s razor? She’d always used George’s – infuriating him – to shave her armpits. He didn’t like hairy women. Of course, she could have bought her own razor during the last three months, but somehow she hadn’t got round to it.

You’re the only woman alive at the end of the twentieth century, Louise had written to her last week, who still believes that frogs turn into princes. And now you’re disillusioned because the opposite happened. So what, Louise wrote. Join the club.

Griet wished she could be as cynical as her friend. But she wanted to cry over her house that felt as abandoned as an Afrikaans church on a weekday. She stood in the kitchen where she’d never been plagued by cockroaches and stared moodily at the unwashed clutter in the sink. Mostly glasses, she noticed, wine glasses and whisky glasses and almost all the other glasses in the drinks cabinet. It looked as though her husband had had a party every night since she left. Or was drinking himself to death in remorse, she thought hopefully.

For a moment she contemplated turning on the tap and doing the dishes, but she managed to stop herself in the nick of time. It was too late to play the kind fairy now. As if he’d ask her to come back if he came home to a clean kitchen tonight.

It didn’t look as though he was eating much. There were only three plates in the sink. In the fridge she found a dozen cans of beer, a couple of bottles of wine, a box of milk (sour: she sniffed against her will), a heel of mouldy cheese and four eggs. She wondered what the children ate when they came for the weekend. She wondered whether there was toilet paper in the bathroom. And whether he’d remembered to pay the telephone account in time and water the rosemary bush near the back door regularly and to leave a window open at night for the neighbour’s peripatetic cat.

It had nothing to do with her any more. She’d only come to get clean clothes and a couple of books, she reminded herself. She suddenly noticed that he’d removed all her photographs and postcards from the pinboard next to the fridge. It’s fucking final, she realised, and fled blindly from the kitchen.

In the bedroom she could smell him again, the unlikely combination of sweat and soap and smoke. But she didn’t smell another woman, thank God. She wouldn’t have been brave enough to cope with that. Not while her own smell still lingered in the corners.

Grandma Hannie’s house had always smelt of food, of baked bread and stewed quinces, and sometimes also of animal carcasses on the butcher’s block. The smell of blood always took Griet back to that house. That was where she’d smelt her own blood for the first time, on the day of Grandpa Big Petrus’s funeral.

Symbolic, she thought afterwards, but at the time she hadn’t seen anything symbolic in the situation. Just the cruelty of fate to choose the day she had to wear a lily-white funeral dress. The family thought she wouldn’t stand up in church to sing with the congregation because she was so heartbroken. Shame, the local women whispered sympathetically, she was the apple of her grandpa’s eye.

She left the church after everyone else, thankful and relieved that the dress was still unstained.

That night she felt that her life was over, as though she’d been buried along with her grandfather. She was still thirteen, just like yesterday, but suddenly she had to behave like a grown-up. Tomorrow she’d have to sit with the women in the kitchen, sweating under the strips of yellow fly-paper that dangled from the ceiling, while the other children squealed in the farm dam.

She tossed and turned and was roused from her uneasy sleep in the early morning by the saddest sound she’d ever heard. Grandma Hannie was singing a hymn, her reedy voice quite out of tune without her husband’s lead, but determined to soldier on alone. ‘On mountains and vales, the Lord is o’er all …’ Somewhere, Griet thought, Grandpa Big Petrus was smiling satisfiedly. And it was only then she could weep for his death for the first time.

Griet looked longingly at the double bed, the heart of the house, the hub that her life had turned on for seven years. She and her husband had never sung in their bedroom. She’d inherited her grandmother’s tuneless voice and her husband preferred philosophising to singing. He believed it was only emotional Italians and sentimental Germans who liked to sing.

Griet yanked the wardrobe open, suddenly in a hurry, and threw a bunch of hangers on to the bed. She had to get out of this house as quickly as possible and never come back. It was like Pandora’s box, the memories that crept out all over from the moment she’d unlocked the front door. It was worse than Pandora’s box. Pandora had at least kept hope.