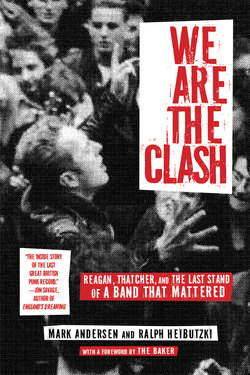

Читать книгу We Are The Clash - Mark Andersen - Страница 9

Оглавлениеchapter two

what is clash?

Strummer and Simonon return to their punk roots, late 1983. (Photo by Mike Laye.)

Bernard Rhodes and Kosmo Vinyl, with Peta Buswell, head of the NYC Clash office at center. (Photo by Bob Gruen.)

We have two choices. We can give in and watch social destruction and repression on a truly horrific scale, or we can fight back . . . Faced with possible parliamentary destruction of all that is good and compassionate in our society, extra-parliamentary action will be the only recourse left for the working class.

—Arthur Scargill, NUM conference, July 4, 1983

We’ve been away for two years—and I’ve been trying to come to a decision. I’ve been thinking, What the fuck am I doing living? What am I supposed to do with it? How come you all come see it? Where is it going, what was it going, what is Clash, where is Clash, who is Clash?

—Joe Strummer, Barrowlands Ballroom, February 10, 1984

On Saturday, September 10, 1983, readers of New Musical Express (NME) were startled to learn that The Clash—as they had known it—had ceased to exist.

A band statement read simply, “Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon have decided that Mick Jones should leave the group. It is felt that Jones had drifted away from the original idea of The Clash. In future it will allow Joe and Paul to get on with the job The Clash set out to do in the beginning.”

Clash biographer Marcus Gray later wrote that the news “hardly came as a surprise,” but it was to at least one person: the author of the NME press release, Kosmo Vinyl. “I was shocked by this,” the Clash spokesperson insisted years later. “I was not part of the process that decided whether or not this was going to happen—or maybe I was, but I wasn’t aware of it.”

Vinyl was well acquainted with the tensions, but never believed it would come to this. Yet it now fell to him to somehow help reassemble that most alchemical of creations: an ambitious and successful rock band that had ejected the authors of two and a half of its three hit singles in slightly more than a year.

Vinyl: “In the end, the situation was presented in a certain way: ‘Are you on board with this, or not?’ And I decided to go with that. The band, what it represented—it all was too important for me to stand aside.”

This was no small decision—and other members of the Clash camp made different ones in the “him or us” atmosphere that developed after the purge of Jones. The Baker recounts, “I decided to wash my hands of the whole situation. I never told Joe or Paul that I quit, but I said goodbye and left. They never called me, and I never called them.”

Equally committed partisans came to different conclusions. Like Johnny Green, The Baker had been suspicious of the upstart. Vinyl, however, had earned their grudging respect. Now, as Rhodes’s consigliere and a band mouthpiece second only to Strummer, Vinyl was key to meeting the challenges ahead.

“Now Mick’s gone, and we’re thinking, ‘We have Joe and Paul and a drummer,’ you know?” Vinyl recalls. “So we’re not starting from scratch here. How are we gonna go forward now?” If the exact path wasn’t immediately apparent, one agenda item was: a new guitar-slinger, with both the needed skills and of sufficiently stalwart ideological stock.

* * *

Five days after the news of Jones’s expulsion, seven people gathered for a meeting at 10 Downing Street. If far less publicized than the internecine strife in The Clash, the meeting would prove considerably more consequential.

The public would only learn about this secret conclave more than thirty years later via a newly released document, marked, “Not to be photocopied or circulated outside the private office.” Attended by Margaret Thatcher and her closest aides, the meeting concerned Ian MacGregor’s plans for the British coal industry.

British Steel had already undergone drastic layoffs. Now coal mines—known in the UK as “pits”—were on the bull’s eye. According to the meeting notes, MacGregor’s closure program had “gone better this year than planned: there had been one pit closed every three weeks,” with the workforce shrinking by 10 percent.

This was wrenching amid the worst downturn since the Great Depression, but the Coal Board now meant to go much further: “Mr. MacGregor had in mind that over the years 1983–85 a further seventy-five pits would be closed . . . The manpower in the industry would be down to 138,000 from its current level of 202,000.” Almost one-third of all coal miners stood to lose their jobs in the next two years.

This was political dynamite, as was made clear by the precautions taken to avoid disclosure of the plan: “There should be no closure list, but a pit-by-pit procedure,” the notes record before coming to the final paragraph: “It was agreed that no record of this meeting should be circulated.” Another memo written a week later stated that the group would continue to meet regularly, but that there should be “nothing in writing which clarifies the understandings about strategy which exist between Mr. MacGregor and the secretary of state for energy.”

The secrecy was essential, for the plan was ruthless. As the BBC reported in 2014, “Two-thirds of Welsh miners would become redundant, a third of those in Scotland, almost half of those in northeast England, half in South Yorkshire and almost half in the South Midlands. The entire Kent coalfield would close.”

It was precisely this sort of wholesale assault that Arthur Scargill feared. While some disliked him as a Marxist firebrand, Scargill’s landslide victory for the union presidency in 1981 reflected both his popularity and the rank-and-file sense that a decisive showdown with the government was coming.

The sweeping Tory election victory raised the stakes. In 1981 Thatcher had backed down before a NUM challenge; now her position was strengthened considerably.

At the NUM national conference held shortly after the Tory landslide, Scargill issued a call to action. Warning that Thatcher sought to destroy the industry not only due to lack of profits, but for revenge, he evoked the specter of fascism in 1930s Germany: “We have two choices. We can give in and watch social destruction and repression on a truly horrific scale, or we can fight back.”

NUM president Arthur Scargill, with United Mineworkers of America hat. (Photographer unknown.)

Scargill made his position clear: “I am not prepared to quietly accept the destruction of the coal-mining industry, [or] to see our social services utterly decimated. Faced with possible parliamentary destruction of all that is good and compassionate in our society, extra-parliamentary action will be the only recourse left for the working class and the Labour movement.”

These were powerful words—and they would be used against him. Scargill matched Thatcher as a polarizing figure, with the same air of righteousness. Like the Tory leader, he inspired fanatical followers, but also bred determined enemies and could alienate less-convinced sectors.

Scargill’s call for “extra-parliamentary action” was simple reality: Thatcher controlled Parliament, so the only way to resist now lay outside that institution. Still, darker notions of a Communist coup d’état would be spun out of the same thread, as the Tories portrayed the matter as a struggle for democracy, not jobs.

Thatcher was not above fearmongering, sketching Scargill as a dangerous radical out of step not just with Britain but with his own rank and file. MacGregor echoed this, describing Scargill’s speech as “a declaration of war” from an antidemocratic bully seeking to overturn the duly expressed will of the country.

This conveniently overlooked the fact that a majority of British voters had never pulled the lever for Thatcher. Even though the vagaries of the UK system had awarded the Tories a veto-proof majority in Parliament, their support in 1983 had actually dipped to 42.4 percent, some 700,000 less votes than in 1979.

Moreover, if Thatcher was so assured of the legitimacy of this path, why not share the plans with the public? Clearly she feared the consequences—so she and her minions would subvert the open discussion essential for democracy by never admitting to the true scope of the sweeping mine-closure program.

While there were reasonable arguments to be made over the economic health and future of coal as an industry, the central thrust of the Tory scheme was political, as was made clear by the existence of something titled, “The Final Report of the Nationalised Industries Policy Group.”

Nicknamed “The Ridley Report” for its author, Nicholas Ridley—Tory free-market evangelist and close Thatcher ally—this plan was drawn up in June 1977, just as punk was exploding across Jubilee-era Britain. The report contained many contentious suggestions, but most explosive was a two-and-a-half-page “Confidential Annex” entitled, “Countering the Political Threat.”

This addendum identified the nature of the “threat” and suggested a solution. Like Thatcher, Ridley took for granted that the NUM—by virtue of its organized militant strength and unique importance as the provider of electricity that ran the entire British economy—had become even more dangerous than the Labour Party itself. Any successful Conservative government in the future would need to tread carefully, aware that confrontation was more than likely.

Ridley did not fear this struggle. But he did seek to ensure that the battle would come on terms favorable to—or even chosen by—the Tories.

Ridley urged that coal stocks be increased to prevent power cuts in the event of a prolonged strike. Plans should be made to import coal from nonunion foreign ports, with nonunion drivers recruited by trucking companies, and with dual coal-oil generators installed. While these measures would increase costs, they would significantly reduce the miners’ leverage.

Police would also need to be equipped with riot gear and trained in mobile tactics to counter “violent picketing,” i.e., the flying pickets. Legislation should be passed to make such picketing illegal to whatever extent possible. The police force was to be readied to use as a blunt instrument in what was ultimately a political battle.

The Ridley Report was a map for winning a war with the unions, especially the NUM. Such inflammable material is hard to keep secret, and the plan was soon leaked, appearing in the UK press in early 1978.

That error had become a learning experience. Now that the game was afoot, a much tighter lid was clamped on preparations for the coming war. The election had given the leverage needed to put the Tory plans into action—all that stood in the way of the free-market renaissance they craved was the NUM.

* * *

While Thatcher was drawing up battle plans, so was Joe Strummer—and his weapon was The Clash. But for many people, that entity no longer existed: The Clash was Strummer-Jones-Simonon-Headon. Vinyl called this the “John-Paul-George-Ringo Syndrome”—a band was certain people; no less, no more.

This purist idea was widely flouted in an industry ever more fixated on money. Still, it spoke both to an artistic reality—the mix of certain people could have a unique magic—as well as a compellingly romantic notion of rock bands made of friends who rise from the garage to the world stage together.

Jones himself had raised this question with rock journalist Mikal Gilmore in June 1982 by noting that the post-Headon Clash “feels like a new band now,” even wondering aloud if they should be called “Clash Now” or “Clash Two.” Such musing seemed odd given that The Clash had started out with their then-current drummer Terry Chimes, recording their first record with him. Moreover, The Clash had played the landmark “Anarchy” tour with Sex Pistols, Heartbreakers, and the Damned—as well as other key shows—with drummer Rob Harper.

Jones’s idealism shines here, as such attachment to specific members had become unusual. By the 1980s, most bands freely shed members, even losing central catalysts like Syd Barrett (Pink Floyd) and Brian Jones (Rolling Stones), but still rolling forward on artistic and, of course, commercial terms.

But what if “The Clash” was more than a band—if it was an idea? Was it the specific people or the mission that mattered? Jones’s rival Clash cofounder Rhodes believed in the latter notion, which was, in its way, just as idealistic as its opposite.

Rhodes was taken by the idea that The Clash could be like an army platoon, with no soldier irreplaceable and the shared objective paramount—a metaphor that Strummer and Simonon also embraced at the time. Indeed, Strummer would soon go so far as to argue, “I hope that if I start acting funny, I’d be fired, and The Clash would roll on without me.”

This could be taken to an extreme. The Baker skeptically recalled Rhodes’s admiration of the Puerto Rican bubblegum pop band Menudo whose members shifted at the whim of their producer/creator Edgardo Diaz. He later laughed: “Of course, Bernie would like that—it gave him all the control!”

This comparison might seem ridiculous. Yet the original Clash had hardly come together as teenage friends in some mythical garage. It was manufactured out of Jones’s striking musical vision, but equally assembled by Rhodes’s instincts and ideology. Miraculously, this fairly mechanistic mating had actually worked.

The Clash coalesced more deeply than Malcolm McLaren’s Sex Pistols, whose self-destruction was more or less assured. Strummer and Jones had chemistry as a writing team and—with Simonon added to the onstage mix—as an arresting live juggernaut. Headon soon added to this, helping to propel their ascent.

Could lightning strike again? For Strummer this was no academic matter. While marching in step with Rhodes, he also knew there was something more mysterious and organic required; more than anyone else, it would be up to him to make the new “platoon” cohere as an artistic and spiritual entity.

The pressure was immense. Strummer admitted he “was thinking all the time . . . maybe too much.” He had a depressive nature and in 1982 had spoken of “some bad times, dark moments when I came close to putting a pistol to my head and blowing my brains out”—an ominous admission given his brother’s suicide.

Although Strummer hastened to add, “If you ain’t got anything optimistic to say, then you should shut up,” his bouts with darkness might have been the natural result of a brain that refused to shut off. He now had more than usual to contemplate, as doubts about his decision to eject Headon and Jones nagged him.

The burden had a practical aspect. After his exit, Jones would pointedly question how The Clash might forge ahead without him, saying, “I hope that their new guys help them write the material.” Strummer hardly needed to be reminded of the hole in the band’s creative core, acknowledging, “If your song ain’t good, you ain’t gonna triumph.” He was already hard at work to meet this challenge.

Michael Fayne, the young recording engineer brought in by Rhodes in 1981 to work at Lucky Eight, the studio at their Camden haunt, Rehearsal Rehearsals, saw the pressure on Strummer up close. “Joe would come in to demo a song, you could tell he was nervous. He would run through the song, just him and guitar. As he did, he’d kind of sneak a peek at me, see how I was reacting.”

Fayne didn’t remember being that impressed by the new songs, but did recall that one tune with the words “This Is England” caught his ear. If Strummer picked up on the lukewarm reaction, he was not deterred. The singer continued to knock out new tunes, to be fleshed out once the band was whole again.

Strummer’s plans were helped when a new guitar player was found via auditions hastily arranged by Vinyl: Nick Sheppard, former lead guitarist of the Cortinas, a defunct first-wave punk band from Bristol in southwest England.

Though the auditions were for an unnamed band, Sheppard had a pretty good idea who it was. As the guitarist recalls, “I was out at a pub not long before the audition came up and ran into Joe, Paul, and Kosmo. I happened to overhear them talking a bit, going on about ‘he’s got to go.’ Had no clue at the time, but in retrospect, it was pretty clear who the talk was about.”

Hundreds came to the auditions, but Sheppard stood out. He was from the same original punk generation as Strummer, Simonon, and the rest. The Cortinas had been popular enough to earn their own brief liaison with CBS in the late seventies, but not so high profile as to be a distraction. Sheppard: “We had the same influences, came up in the same school, if you will . . . We understood each other.”

While the Cortinas scarcely shared The Clash’s politics, Sheppard had solid left-wing credentials: “I grew up in a family of trade unionists and Labour supporters, and I was, in that respect, politically aware—I knew what side I was on.” Finally, Sheppard was a big Clash fan, having seen the band live many times.

Once Sheppard was in the fold, the band went into intense rehearsals. Strummer unveiled more than a dozen new songs, which the new lineup began to hammer into shape. Their work, however, was shadowed by rumors that Jones and Headon were readying their own version of The Clash.

While this prospect gnawed at Strummer’s self-doubt, a less sentimental Rhodes saw it as a direct threat. Jones had been critiqued for working through lawyers while in the band; how much more likely was legal action now?

In strictly commercial terms, “The Clash” had become a lucrative brand, and Rhodes wanted to preempt counterclaims. He urged Strummer to make it clear in song that nothing from Jones and Headon could be the real item.

Sheppard witnessed the dynamic: “You got the sense then that some new songs were ‘made to order’ in a way, that Bernie had said to Joe, ‘We need a song called this or about that.’ Joe would listen, but he is a serious writer, right? So what he would come up with would be his own vision in the end.” The process produced a song that would define the new band to fan and foe alike: “We Are The Clash.”

The title was a bit obvious. Even for a band renowned for self-referential anthems like “Clash City Rockers,” “Radio Clash,” “Last Gang in Town,” and “Four Horsemen,” it seemed a step too far. Predictably, it would be swiftly lampooned as a laughable echo of “We Are The Monkees,” the theme song of another manufactured band favored by Rhodes.

While the song may have started out in that territory, Strummer took it to a deeper and more resonant place. He understood Rhodes’s desire to protect the Clash “brand,” but such an angle struck him as altogether too businesslike. For Strummer—as with Rhodes, ultimately—The Clash was something far more profound than a commercial venture, more than even a band . . . but exactly what?

The surge of right-wing power added urgency. “The world is marching backward fast all the time!” Strummer declared at the time. “Everything I read is bad news, apart from the Sandinista thing in Nicaragua.” A tantalizing idea began to percolate out of his soul-searching. Strummer’s thoughts intersected with Rhodes’s directive, but went beyond.

Strummer’s inspiration began with the Clash audience. Ever eager to engage with fans, Strummer had been touched by encounters on the 1982 tour of the Far East. In Japan, for example, one conversation had turned to family members killed in the US atomic attacks on Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Strummer was already riveted by the nuclear danger; this made it even more real.

Strummer shared another anecdote from the tour with Sheppard, who recalls: “These aboriginal guys came to talk to him after the [Queensland, Australia] show about their situation. And then he got a phone call saying that the police had gone and busted up their house, because they’d dared to go backstage and talk to these white guys.” The ugliness of the incident, the deep racism it represented, and the courage of the fans “really left an impression on him,” according to Sheppard.

The Clash had once articulated voices from Brixton, Camden Town, Notting Hill, the West Way. Now they had come to embody something broader, rising up from the global grassroots: a rainbow of peoples, united by a shared spirit. The fans’ enthusiasm and ability to relate their struggles to themes in Clash songs affected Strummer, fueling the band’s own ambitious musical and topical trajectory.

This growing fusion also reflected the fact that The Clash came alive in concert—in Strummer’s words, “working together with the audience.” Keeping all of this in mind, the singer wrote a couplet that became the central metaphor of the new song: “We can strike the match / if you spill the gasoline.”

First heard as a demo recorded at Lucky Eight in November 1983, “We Are The Clash” utilized blunt yet cannily arranged butcher-block chords to stake its claim. Propelled by Howard’s powerful drumming, its chorus asserted, “We are The Clash / we can strike the match” with the follow-up line “if you can spill the gas” repeated twice and drawn out, the focus shifting from artist to audience, to what could be created together. Fittingly, it seemed designed for a gigantic sing-along.

The song was now less about “protecting the brand” than making it clear that—as Strummer would later insist—“when I say that ‘we are The Clash,’ I’m talking about considerably more than five people.” The song was an example of how a nudge from Rhodes could result in something profound in Strummer’s hands.

This exploded the concept of The Clash, launching it past the realm of “rock band.” If the song embodied Strummer’s punk populism, other lyrics tied the fate of this fusion to larger global struggles. “We don’t want to be treated like trash,” the song insisted—yet across the world so many were, in so many ways.

The end of 1983 was a particularly powerful moment in this regard, for reasons both practical and symbolic. Strummer had long been a fan of writer George Orwell. This independently minded British socialist had authored the dystopian classic 1984, which portrayed a suffocatingly oppressive world where language itself had been corrupted to serve as a tool of social control.

Orwell’s blistering critique—aimed equally at fascism and Stalinism—reflected his belief that relentlessly seeking and speaking truth was central to human liberation. The idea resonated with Strummer, as did Orwell’s critiques of British imperialism and the violence of poverty, and his desire to abandon his privileged background to be in solidarity with the poor and working classes. The singer’s emphasis on truth telling as the core of The Clash’s revolutionary mission echoed Orwell’s own imperatives.

The references were everywhere: the band’s debut single “1977” ends with a spooky echoed “1984!” On the embattled “Anarchy” tour, Strummer had refitted “Protex Blue” with lyrics that warned, “Big Brother is watching you.” Graphics from the film versions of 1984 and another Orwell masterpiece, Animal Farm, appeared in The Clash songbook and on the cover of 1978’s “English Civil War” 45, respectively. Strummer had even revised history once, suggesting that the 101ers’ name was a reference to Room 101, 1984’s torture chamber.

Orwell had intended 1984 less as prophecy than as a warning of what was already unfolding in the late 1940s when the book was written. Still, its impact imbued the year 1984 with a sense of destiny. Much like 1977—the year when “two sevens clash,” according to some Rastas—the fast-approaching new year had an ominous sense of converging, perhaps even world-rupturing forces.

“The Clash,” then, might not simply be a band and its audience, but also this charged moment, carrying the sense of an era’s turning, for good or for ill.

This conception of The Clash could seem pretentious, yet was of a piece with the band’s immense ambition. It suggested why, in Strummer’s mind, The Clash was urgently needed right now, not simply as a politicized pop group, but as a cocreated project of artist and audience, as a spirit of struggle.

The high stakes and global sweep involved were evoked by the existing words of “We Are The Clash.” The song opened with a list of peoples—“Russians, Europeans, Yankees, Japanese, Africans”—invited to a “human barbecue,” where “twenty billion voices / make one silent scream.” This Edvard Munch–like image suggested worldwide nuclear war, a final showdown that no one could truly win.

To Strummer, Reagan appeared to be preparing for just such a conflagration, embarking on the largest military buildup in post–WWII history, while cutting taxes for the rich and slashing programs for the poor. Furthermore, never-ending war against a shadowy enemy provided the justification for 1984’s totalitarian control. This, in part, already existed. Both US and Soviet military planners justified their massive budgets by pointing to the danger posed by the other, a circular logic that drove ever greater expenditures and made war all the more likely.

* * *

On September 1, 1983, tensions between the US and the USSR hit a scary crescendo with the downing of Korean Airlines flight 007 (KAL 007). A commercial flight from Alaska to South Korea, KAL 007 strayed into Soviet airspace for unknown reasons and was shot down, with a loss of 269 lives.

The Soviets had made a terrible error—one repeated when the US shot down Iran Air flight 655 in July 1988, killing 290—out of paranoia fanned by US bellicosity. This meant no less in terms of human suffering, but it mitigated the supposed barbaric intent, and highlighted the perils created by superpower tensions.

Amid all of this, the US invaded the Caribbean island of Grenada in October 1983. Touting a supposed Communist threat to the region, Reagan used the chaos following a bloody coup against Grenadian leader Maurice Bishop—a Cuban ally—to intervene. The supposed aim was protecting American students on the island; the result was the installation of a new US-friendly regime.

For the first time since the Vietnam War, the US was asserting its imperial prerogatives over its “backyard.” The message to the Sandinistas and their Cuban and Soviet supporters was clear.

George Orwell’s 1984 hung heavy over Clash-land. (Artwork by Eddie King.)

As 1984 approached, catastrophic confrontation seemed increasingly inevitable. Strummer expressed this fear in another new song, “Are You Ready for War?” Musically, this was one of the strongest of the new batch, and analogous to the bracing punk-reggae of “Police and Thieves.” The song rose off a funky groove but also brought the punk hammer down, creating something new and exciting. Sheppard contributed cutting-edge “DJ scratch” hip-hop guitar noise.

The demo’s other dozen songs cataloged additional concerns. Some were new takes on old topics: the personal and political dangers of drugs (“Glue Zombie” and “National Powder”) and US foreign policy (“The Dictator”). Others like “Sex Mad War”—an attack on rape and pornography from a feminist perspective, riding on a hopped-up rockabilly chassis—explored newer lyrical territory.

A notable focus on the trials of the British working class came through in a trio of hard-hitting songs. “This Is England”—the song that had caused Fayne’s ears to prick up—began as a folky dirge spinning out dark images of “a gang fight on a human factory farm,” only to rev up by song’s end, with galloping guitars, bass, and drums driving home a bleak commentary on Thatcher’s Britain.

The use of the term “factory farm” was striking. These words had been popularized by UK animal rights activist Ruth Harrison: “Factory farms are often owned or highly influenced by corporations and the guiding principle of these businesses is efficiency, producing the most produce and hence profit for the least expense,” with little regard for the consequent suffering—a trenchant critique of Thatcher’s aims.

A second song, “In the Pouring Rain,” opened with clarion chords, followed by words that portrayed a gray vista, drenched in a downpour that evoked the hopelessness settling over the depressed north of England: “I could see as I rode in / the ships were gone and the pit fell in / a funeral bell tolled the hour in / a lonely drunkard slumbering . . .” While the music started off a bit stiff, not quite bringing the aching words to life, dynamic guitar interplay after the chorus lifted the song.

Best of all—musically and lyrically—was the blistering “Three Card Trick,” which likened the capitalist system to a famously fixed card game, three-card monte. The song opened with crushing power chords propelling a stark indictment: “Patriots of the wasteland / torching two hundred years.” Strummer struck directly at the claims of Thatcher and Reagan to be making their countries “great” again, while creating a desert of deindustrialization and unemployment.

This was not overstated. Journalist William Kleinknecht would later describe Reagan as “the man who sold the world,” a critique that could just as easily apply to Thatcher. The duo preached the gospel of “creative destruction”: clearing away the old and exhausted to make way for that which was new and improved.

Such claims were not far from punk’s “Year Zero” rhetoric, but Strummer was having none of it. His focus was on people, on their pain, as “Trick’s” follow-up lines show: “Bring back crucifixion / cry the moral death’s head legion / use the steel nails / manufactured by the slaves in Asia.”

As with the best of Strummer’s lyrics, these lines pack a book’s worth of critique into nineteen words. Subtly equating the Nazis and the Moral Majority, the Clash frontman undercuts the right-wing Christian “law and order” agenda by evoking their crucified founder, while tearing the veil off the interconnected realities of first-world deindustrialization and third-world exploitation.

A more succinct indictment of the Thatcher-Reagan project was hard to imagine. More concretely, the steel references in both “Three Card Trick” and “This Is England”—as well as earlier in “Straight to Hell”—show how Strummer was aware of the devastation of British industry, and what it represented: the unraveling of a social compact forged in the fires of the Industrial Revolution.

Strummer was ambivalent about the cost of that bargain, as his lyrics elsewhere comparing factory work to slavery suggest. The singer argued, “For the past two hundred years we’ve all been had by an industrial society . . . that only needs workers to fuel its factories and furnaces and whatever. I feel [humanity] has a better destiny . . . There’s a better life to be lived for everybody and by everybody.”

Yet Strummer saw the immense suffering created when factories, mills, and other enterprises closed, taking jobs with them: “Supposedly technology and science was going to save the world, and we should be going forward into a bright future, but [instead] it’s recession, close a factory down, put people out of work.”

To be fair, these trends had predated Thatcher and Reagan, and resulted from globalizing forces that were extremely difficult to resist. But Thatcher in particular was an unapologetic defender of cutting the lifelines for many struggling industries—and those who worked there—in the name of efficiency.

In “This Is England,” Strummer encounters a female mugger holding a blade made of “Sheffield steel,” referring to the most renowned UK steel town, now devastated by cuts. The reference was clear: most of those workers left jobless saw Thatcher as the one who had slashed their industry’s throat.

Steel had been one of the pillars of the British economy since the Industrial Revolution, and its decline could rightly be viewed as a national tragedy. Still, there was one commodity that was even more fundamental: coal.

Orwell noted this in Road to Wigan Pier: “Our civilization is founded on coal. The machines that keep us alive, and the machines that make machines, are all directly or indirectly dependent upon coal. In the metabolism of the Western world the coal miner is a sort of caryatid upon whose shoulders nearly everything is supported.” Even steel depended on coke—a coal derivative—for its manufacture. Without coal, the lights went out, metaphorically and literally.

The work could be horrific. Untold thousands had been lost in mining disasters and from diseases like black lung. This underlined the cost at which our world had been built, and who paid the price. As such, coal miners’ rights to better conditions and pay resonated across history—especially in British society.

Once British miners had built a strong union, their unique combination of moral claim and practical power gave them a status unmatched in the country’s workers’ movement. Given their historic role, the miners would tend to have public opinion on their side, and a direct way to inflict pain on the government by causing power cuts—unless proper preparations were made in advance.

By late 1983, Thatcher was keen to complete just this. According to Charles Moore’s authorized Thatcher biography, “Preparations for the inevitable confrontation continued. ‘The first priority,’ Mrs. Thatcher told the meeting, ‘should be to concentrate on measures which would bring benefit over the next year or so.’”

Aware of the growing tension, the miners took action. As Moore notes, “The first rumbles of confrontation were felt on 31 October 1983, when the NUM began an overtime ban in protest at the current pay offer and rumors of pit-closure plans. In a meeting of ministers two days later, which Mrs. Thatcher chaired, it was agreed that the danger of a strike was ‘likely to increase in the second half of 1984.’”

If anything, the NUM’s prohibition of overtime—which would effectively cut miners’ pay, but also slow government efforts to build up surplus coal stocks to guard against a strike—was late in coming. Although Moore reports, “Ministers assumed that the NUM would not be so foolish as to begin a strike in the spring just when demand for coal would fall,” this seems disingenuous, for the Tories would surely seek to provoke a strike at the most advantageous moment.

* * *

As Thatcher baited her traps, The Clash seemed to have bounced back in record time. While a couple of cuts on the demo seemed hardly advanced from the rattletrap grit of the 1976 Clash—or even the 101ers—the tape as a whole suggested a promising new unit. Far from a narrow punk fundamentalism, the songs conveyed a stronger rock foundation while still leaving room for other flavors.

Strummer knew that, despite any loftier intent, The Clash would rise or fall on its power as a band. Interviewed at Lucky Eight after the demo’s completion, he seemed resurgent, offering paeans to rock’s power: “The real things came off the street, invented by lunatics, madmen, and individuals, they’re the ones that last. I’m talking about your actual rock and roll, rockabilly, even psychedelic insanity rock and punk rock—these things weren’t created by the industry. The industry was running after these things, going, ‘What is it? Where can I get some?’”

The singer sounded ebullient about the new lineup: “In this place, seven years ago, we decided we were going to be bigger than anybody else—but still keep our message. And, in a way, there was no way of avoiding those things that we fell into. So, it’s been good rebuilding The Clash here because we’ve really come full circle, starting out here and coming back here now.”

Strummer then turned philosophical: “You mentioned that it was ‘unfortunate’ that we had to go through these things but I think that is the wrong word. I think it was inevitable. You don’t get issued with a map about how to avoid these things. I think it’s a question of learning, of being burned by life and learning from it.”

Asked finally to share his greatest thrill about The Clash, the singer said: “I get a kick out of it when someone comes up to me and says, ‘Because of your group I went and retook those exams that I failed and passed them all!’ I get a kick of hearing how we influenced people’s lives. ‘Because of your group I am majoring in political science.’ I get a lot of stuff like that.”

This power was real, but the responsibility it entailed was immense. For now, Strummer laughed at the thought that this role might bring him unbearable pressure.

Pieces seemed to be falling into place. Not long after the demo’s completion, however, a wild card was introduced: Greg White, who was living in Finsbury Park, was suddenly drafted as the second guitarist in the new Clash.

This most likely began as an effort by Rhodes to reduce Strummer’s burden. Vinyl was startled but supportive: “I don’t remember exactly where it came from, but I’m thinking it came from Bernard. Joe would not play guitar as much onstage and we would get two guitar players.” And, Vinyl noted, “there were five in the original Clash lineup,” recalling the early guitarist Keith Levene.

Vinyl was surprised by this sudden turn, but it hit Sheppard much harder: “Was I happy? Of course not. One day it was just announced that another guitarist would be joining us. I had no say, and it was hard not to take it personally, even if it made some sense musically, and there had been five in the beginning.”

The move acknowledged another reality: Strummer was a spirited but rudimentary guitar player who, by his own admission, was able to “jam out a few chords but couldn’t do any fiddly bits.” In the heat of a performance, his playing could become even more hit-and-miss, as he lost himself in the moment, “looking for the ultimate wipe-out,” as he once described his attitude toward performing.

In 1982, Jones noted this challenge: “Joe stops playing the guitar a lot, and those are moments where the instrumentation could use a bit of embellishment, so me hands are going all the time.” Though Jones tried “to hold it all together,” he did so with only mixed success, as live tapes from that era sometimes showed.

Live performance is not entirely about hitting all the right notes. Nonetheless, there was wisdom in the idea that songs written for two guitars should be played by such. This interplay was part of the power generated “when two guitars clash” as Belfast’s Stiff Little Fingers put it in a tribute to the band.

This promised to be a boon to Strummer, who was now freed “to go loopy,” as he laughed later. The rub came in finding the right person for this job.

If Sheppard had been a somewhat known commodity, White was anything but. Later Sheppard would admit to uncertainty about whether White had ever played publicly before his gigs with The Clash. White actually had, but he acknowledged the largest pre-Clash crowd he had faced was perhaps less than two dozen. Even so, he had the skills and the looks—and a serious attitude. That’s likely what won him the job.

Feeling lost in a dead-end life, working at a warehouse, White was intrigued and annoyed in equal measure by a NME ad in that read, “Wild Guitarist Wanted.” He passed an initial telephone interview, and joined dozens of guitarists summoned to audition for an anonymous band.

Unlike Sheppard, White only had a vague notion of what band he might be joining. “They kept it very hidden,” he recalls. “I wasn’t totally sure, but there was a rumor that it was [The Clash]. Some people were saying it was Tenpole Tudor, and a few people were saying it was somebody else.”

Auditions took place on The Clash’s Camden Town stomping grounds, at the Electric Ballroom. There, White and the others cooled their heels until it was time to play with a prerecorded backing track. Strummer and Simonon were nowhere to be seen, leaving Rhodes and Vinyl to run the proceedings.

Bored by the process, White entertained himself with a few beers he had smuggled in. He took the stage angry and a bit drunk, swiftly breaking a string, but playing straight through what White later described as “a load-of-crap electronic rhythm-and-blues track,” then stalking off in a huff.

By musical standards, it was hardly a successful audition. But while White’s skills couldn’t match those of some of the other players, his aggro caught the attention of Rhodes and Vinyl, who tailed him outside to get contact information. Later Rhodes triumphantly told Strummer and Simonon, “We found a real street punk!”

The move was not entirely ludicrous, as White had been a fervent fan of the band and often in its audience. He no longer dressed “punk,” but that was easy to address. As White later laughed, “When I joined The Clash, I basically reverted to how I had looked a few years before, as a teenage punk!”

This daring choice showed how unbusinesslike The Clash remained in key regards, operating by punk instinct rather than commercial calculation. Yet it was not without danger. Sheppard noted a bit ruefully later, “The problem is, when you choose someone for their attitude, that’s what you get: their attitude.”

There was little time for reflection, for Rhodes was not allowing much time for the new platoon to solidify. His aim was to get back on the road quickly, returning to the vicinity of their embattled last show with a tour of California in late January.

The original idea had been to play a free gig to erase the lingering bad taste of the US Festival. That was now deemed impractical, given legal worries and the need to make money to fuel the retooled Clash machine, so a seven-date tour was planned instead. As White officially joined the band just days before Christmas, this gave them less than a month to get ready.

One further adjustment was needed. “Greg” was deemed an insufficiently punk name, so White was redubbed “Vince” in honor of early rock heroes Gene Vincent and Vince Taylor. White went along with the change grudgingly, seeing it as evidence of a controlling—and superficial—image consciousness. It was not the last time that he would be dissatisfied with life in The Clash.

The new Clash amid the worst joblessness since the Great Depression, early 1984. (Photo by Mike Laye.)

Less irksome to White was a rigid antidrug line, newly instituted within the band. The edict did have some omissions. “Since alcohol was not on the list of banned substances, it was no skin off my nose, really,” White later recalled with a chuckle. Sheppard: “We were set down early on as a group and Joe and Paul made it clear that we weren’t to be doing these things.” Dropping drugs beyond alcohol was also not a big issue for Sheppard: “I had been considering giving [pot] up anyway, for what it does to your short-term memory.”

This stand made sense, given the desire for a new start for the band. Yet the ban was striking because it included marijuana, a longtime Clash staple.

Some were skeptical, suspecting a Rhodes edict or yet another dig at Jones, whose fondness for pot and cocaine was well known. Perhaps these dynamics played a role, but more likely this was a natural evolution out of long-standing concerns.

Early punk had denounced drug-addled hippies and similarly impaired rock stars. Some in the movement like Rhodes and Vinyl saw such stances as serious and self-evident, but many punks simply seemed to disdain “other people’s drugs” while indulging in their own faves.

The Clash had long inhabited this ambivalent space. Strummer critiqued heroin in 1976’s “Deny,” and “Complete Control” took a swipe at “punk rockers controlled by the price / of the first drugs we must find.” Yet the singer referred to himself as a “drug-prowling wolf” in “White Man in Hammersmith Palais.” Speed came up matter-of-factly in “London’s Burning” and “Cheat” had similarly offhand chemical references. Strummer’s relationship with drugs was clearly complicated.

During a spring 1977 interview with NME journalist Tony Parsons, Strummer even defended drug use, claiming he “can’t live without it,” yet admitting, “If I had kept doing what I was, I’d be dead.” This could have been just a bluff; Strummer is noticeably aloof during the interview, and letting down his guard with the media would have been off the Clash party line at the time. Still, there may have been more truth than sullen bravado in Strummer’s admission.

One of the few substances Strummer roused himself to critique to Parsons—who would later slam all drugs save speed in The Boy Looked at Johnny, the 1978 punk broadside cowritten with fellow NME writer Julie Burchill—was glue sniffing, then widespread in Scotland and various lower-income environs.

The new song “Glue Zombie” picked up that thread, reading almost as a belated rejoinder to the Ramones’ “Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue” and “Carbona Not Glue.” Its riff mimics the unsteady lurch of a member of the living dead, with words sketching an unsparing portrait of addiction’s deadly grip: “I am the rebel with the stare of the glue bag / I lost my friend to the smell of gasoline . . .”

Headon’s crisis had pushed Strummer along the antidrug path, as had his own addictive tendencies. According to Chris Salewicz, on the same 1982 tour where Strummer confronted Headon over heroin, the singer—and Jones—had burst into tears upon arriving in Japan to discover pot would be nearly impossible to get.

This new Clash antidrug line joined with a “Sex Mad War” critique of the sexual revolution to bluntly challenge the common “sex, drugs, and rock and roll” mantra. This stance came from a deep if unexpected source.

In Strummer’s revealing chat with Mikal Gilmore in June 1982, he grounded his growing opposition to drugs in rock idealism: “Music’s supposed to be the life force of the new consciousness, talking from 1954 to present, right? A lot of rock stars have been responsible for taking that life force and turning it into a death force. What I hate about so much of that sixties and seventies stuff is that it dealt death as style . . . To be cool, you had to be on the point of killing yourself.

“What I’m really talking about,” Strummer continued, “is drugs. If the music’s going to move you, you don’t need drugs. If I see a sharp-looking guy on a street corner, he’s alive and he’s making me feel more alive—he ain’t dying—and that’s the image I’ve decided The Clash has to stand for these days. I think we’ve blown it on the drug scene. It ain’t happening, and I want to make it quite clear that nobody in The Clash thinks heroin or cocaine or any of that crap is cool.”

“I just want to see things change. I don’t want it to be like the sixties or seventies, where we saw our rock stars shambling about out of their minds, and we thought it was cool, even instructive. That was death-style, not lifestyle. Those guys made enough money to go into expensive clinics, get their blood changed—but what about the poor junkie on the street? He’s been led into it by a bunch of rock stylists, and left to die with their style.”

In the end, Strummer sounded humble yet committed: “I guess we each have to work it out in our own way—I had to work it out for myself—but The Clash have to take the responsibility to stand for something better than that.”

Simonon echoed this when Gilmore asked why The Clash had been able to persist: “You’re talking about things like corruption, disintegration, right? I tell you what I’ve seen do it to other groups: drugs. I’ve been through all sorts of drugs. At one time I took them just for curiosity, and I learned—it’s not worth it. It’s like a carrot held in front of you, and it’s the downfall of a lot of bands we’ve known.”

The bassist bluntly stated a new Clash directive: “We just cut it out—we don’t deal with that stuff anymore. I’d much rather use the money to buy a record, or a present for me girlfriend, or phone me mum up from Australia.” Asked if the band would share that position with Clash fans, Simonon was again direct: “Sure. I don’t see why not. I think that’s part of what we’re about, is testing our audience.”

Neither Simonon nor Strummer was addressing drugs here in a facile, practiced way, as if under orders. These parallel insights, shared separately in mid-1982, when Jones was still in the band, suggested why the duo continued on together.

This orientation could help to purify a Clash sullied by drugs and rock-star behavior, and provide solid footing amid the moment’s immense challenges. It suggested deep soul-searching about what The Clash was meant to be, for what it should stand. Of course, the spirit could be willing, but the flesh might yet prove weak.

The test was to begin when the new Clash met its old audience, beginning at the 2,000-seat Arlington Theatre in Santa Barbara on January 19, 1984. To some, this California tour made little sense. Sheppard: “I thought it was ridiculous that we went straight onto big stages. I said, ‘Why don’t we do some small club gigs, unannounced, just to find our feet?’” Rebuffed, Sheppard was nonetheless excited to play live, which tended to wash away his doubts.

His equanimity was not universal. While the band had begun to click in practice, White was nervous about playing out. Sensing this, Strummer took the young guitarist aside. As White wrote later, “Joe began talking about a return to basics . . . a new blistering Clash burning with the fire they’d had at the beginning. A new Clash rising up from the ashes with a bunch of short, sharp songs that would redefine what the band was about and reestablish its credibility.”

This was Strummer’s new gospel, soon to be shared wherever he went, and it was galvanizing. That the singer segued quickly from inspiration to asking the guitarist to get a haircut didn’t matter. “I was convinced,” White later wrote.

Having conviction helped, but playing with The Clash—even in a relatively cozy venue like the Arlington Theatre—was an enormous jump for the twenty-three-year-old guitarist. White winces at the memory, recalling missed chords and blown cues, overwhelmed by the hurricane of sound and humanity, not able to move and jump as he wanted while trying to play the songs.

Sheppard recognized the challenge: “Vince was completely out of his depth . . . I had played in big spaces as a support act in the Cortinas, but those stages are huge. You can just get lost.” White nonetheless found the show amazing, partly for the same reason—everything was so hectic and very nearly out of control. As it happened, “Out of Control” was the name of one of the band’s most rocking new numbers, one that White favored.

While the song had not made the cut for the live set, “Out of Control” became the motto of this tour and the new Clash in general. Its energy appealed to White, and reflected the lack of commercial calculation involved with the ejection of Jones and Headon and the return to raw, unfashionable punk rock.

As Simonon would later explain, “We feed off the reaction we get from the audience, then we send it right back out, and the whole thing just spirals out of control in a good way. The tour is called Out of Control and that’s kind of why. It’s really a bit of a wind-up of the press.”

There was another meaning as well, reflecting the band’s unsettled legal situation. According to Clash graphic artist Eddie King, “The Out of Control logo was simply photocopied from a Commando comic book and was placed next to The Clash in all flyers and posters in case of possible lawsuits over the use of the band name. Bernard wanted the possibility to either have the word are flyposted between The Clash and Out of Control so that they could tour as Out of Control, or simply have The Clash cut from the top of posters rather than have to set up a whole new print run.”

Taking aim at those who saw the new Clash as wrecking its commercial future, Simonon continued: “We’re portrayed as this band that goes about smashing shit up, and for us . . . the music is the only thing that’s out of control. We like it to be. What good would it be if we just stood there like dead men onstage?”

Backstage after the show, Strummer perched uneasily next to Simonon for a TV interview, smoking a cigarette and wearing a military hat with Out of Control emblazoned on it. Despite postgig exhaustion, the singer was bursting with a barely contained energy, seemingly ready to leap out at the interviewers.

Asked how the show went, Strummer took a drag, made a fist, and launched: “This is the first of many, now we begin. We wanted to strip it down to punk-rock roots and see what’s left, see how it progressed from there.” Slicing the air with his hands, Strummer went on: “I looked around over the past year at all the folks doing shows and making records and I realized that they’d all gone overproduced . . . I realized there wasn’t any piece of vinyl I could hold on to and leap out of a space shuttle with yelling, feel satisfied with like some real piece of rhythm and blues, a Bo Diddley record.” The singer grimaced and balled his fists intently. “You could just hold it in your hands forever!”

Asked how fans responded to this new, raw Clash, Strummer responded, “I think they were took aback a bit maybe because they see us rushing, rushing with the nerves showing in our faces. But we want to take that nervous energy and turn it into power . . . We want our music to deal with reality, and not skip around it.”

As the interview progressed, Strummer’s targets were varied—corporations, drugs, Reagan, Thatcher, current pop music, heavy metal, musical imperialism—and the verbal blows didn’t always connect. Still, the passion was palpable, and the central message clear: “People want something real . . . everything is blando, blando, blando—let’s have a revolt from the bottom up!”

After Strummer rattled off a long list of upcoming tour dates, the interviewer innocently asked about vacation plans. Strummer reared back in disgust, while Simonon retorted, “We haven’t got time for vacation, we’re there for working!”

Strummer jumped in: “There is no time for vacation! Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, their fingers are like that over the button”—hands shaking, mocking an orgasmic eagerness to set off nuclear hell—“there is no time for vacation. It’s time to get down to it, to have responsibility, to use your vote!”

When the interviewer commented that both musicians seemed happy with the new Clash, Strummer agreed: “We are excited, because at last we don’t have to waste our energy on internal arguments. We don’t have to waste our time begging someone to play the damn guitar!”

After more whipping of Jones’s ghost by both musicians, Strummer unleashed a storm of words: “Now is the time to cut out everything that has been wasting your time, time to get serious. You should have high standards . . . I wish everyone would run into street and smash all their records and burn every record store down . . . tell the business we don’t want something they invented . . . Our flesh is about to be flayed off our faces by a firestorm, we haven’t got time to listen to white people play fake black music . . . Don’t support stadium dog rock!”

The fervent, jumbled rant leaped from Strummer’s mouth as if a dam were bursting. The singer was desperate to communicate—to justify the new Clash? To address this scary moment? To rally the troops to action? It’s hard to tell.

Yet both Strummer and Simonon—in his gentler way—communicated an urgency that was far too often missing from the popular music of 1984. Indeed, more passion was on display in this interview than many of their contemporaries evidenced onstage. As Simonon curtly noted, “So much music these days is so tame, you might as well just go back to bed!”

If Strummer and Simonon sensed an impending “Armagideon time,” others acted as if 1984 was nonstop party time. Culture Club’s Boy George and bands like Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet, and Wham! celebrated jet-set lifestyles and club-land glamour, spinning out lightweight synth-pop dance tunes that were highly profitable but eminently dispensable.

Sheppard later dismissed such music: “It’s like people watching the big musicals in the thirties—it’s escapism, isn’t it? People trying to avoid thinking about the hard times.” Mick Jones had aligned himself on the “dance” side of the “dance vs. riot” polarity, illuminating what helped lead to the break as 1984 approached.

While The Clash disdained the club crowd, the band also had to account for its own misadventures—beginning with a confrontational appearance on America’s pop showcase, Entertainment Tonight (ET), filmed during the California tour.

ET cohost Dixie Whatley laid it out: “The Clash have returned to the concert trail for the first time in two years. In that time the politically outspoken group has lived up to their name both inside and outside the band. Two members left, with one of them embroiling the group in a bitter lawsuit. The Clash has also had to endure severe criticism stemming from . . . last year’s US Festival where they accepted a payment of $500,000 in the face of their stance as revolutionaries.”

A defensive Strummer first responded with a shot at Boy George and the new pop scene, then unleashed a passionate sermonette: “There are people out there [who] are sick to their souls. They have been at a party too long, they have been taking drugs too long . . . Drugs are over from this minute now!”

A skeptical Whatley shot back: “You don’t take any drugs at all?”

Strummer raised his hands as if to wave the thought away: “I stopped . . . Six months ago I wouldn’t have any more damn pot!”

Whatley: “Is that true for your whole band?”

Strummer: “They’re not into it either. And we’ve come over here and we are telling people if they want to listen.”

Simonon leapt in: “To get sharp, there is no use in taking a spliff or anything like pot, because it just clouds your mind up.”

Whatley shifted gears, but stayed on the attack: “You’ve been a very outspoken group, but some people say it’s a gimmick.”

Strummer: “Look, there is no time for gimmicks . . . There is only one thing that young people are listening to. They aren’t reading Sartre, poetry is a bore, in school they don’t listen . . . They are only listening to one medium, and that is rock and roll.”

The frontman’s vehemence, paired with live footage of the new band doing “Clampdown” and “I Fought the Law,” made a powerful statement, despite the interviewer’s skepticism. As a snarling Strummer said at the outset of the segment, with the rest of the band flanking him: “Something should be started. We are here to bring up reality and push you in the face with it!”

The Clash brought that confrontational attitude to seven thousand people at San Francisco’s Civic Auditorium. The set was not lacking for rough spots—“Safe European Home” opened as a discordant mess, grating feedback marred “Dictator,” guitars repeatedly went out of tune, and a Simonon-led “Police on My Back” came off flat. While Sheppard did a fine job taking lead on “Should I Stay or Should I Go,” the song’s inclusion struck a false note, even to its singer: “To be honest, I didn’t feel comfortable singing it . . . [I felt] a bit stupid, really.” The Jones-linked song would soon largely disappear from the set list.

Strummer was in fine form, bantering with the crowd. Not all was lighthearted; he introduced “Sex Mad War” by shushing the crowd and urging them “to focus all your minds on sex!” Perhaps anticipating racy rock talk, the crowd cheered.

Strummer cut savagely through the revelry: “Every boy in this world has gone sex mad, there ain’t no satisfaction. This is dedicated to all the victims of the sex-mad war—the women, the women, the women . . .” On cue, the song exploded to life, earning its place on a set list heavy with the band’s early anthems.

Likewise, Strummer segued from joking about the uncontrollable feedback—“We have no intention of playing avant-garde music that sounds like this . . . so we’ll just have to drown it out by some old-fashioned human and wood stuff”—to railing against “Ronald Reagan’s favorite hobby: smashing Central America to fuck!”

Having blitzed through the first show on “pure adrenaline, pure nerve,” Sheppard felt better about the outcome in San Francisco. So did White, whose opening-night jitters—“I didn’t know what I was doing onstage”—gave way to utter abandon: “I just threw caution to the wind. I remember cutting my hand to pieces . . . doing these Pete Townshend windmill things, just fuckin’ going mad.”

The intent was to present a rougher version of The Clash, with Strummer’s passion cranked up to cover the band’s raggedness. The patchy parts were to be expected, given that the five had been playing together for a month.

Some observers were unconvinced. In the San Francisco Examiner, Phillip Elwood argued that the “new Clash lacks some of the old fire,” faulting the new lineup for lack of identity overall, and Strummer for erratic onstage delivery. The San Francisco Chronicle’s Joel Selvin hammered Sheppard and White: “Neither proved exceptional . . . Even keeping their guitars in tune proved a problem for these two green additions to the world’s most famous punk band.”

The quintet continued on the road, playing spaces as out of the way as the Spanos Center in Stockton, California, and as massive as the Long Beach Arena—capacity 13,500—followed by Santa Monica’s Civic Auditorium. Mixed reviews continued, with Ethlie Ann Vare complaining that the new lineup “shows more energy than finesse.” Her verdict was stark: “Yes, the new Clash are taking off in a direction. Trouble is . . . that direction seems to be backward.”

Such slams didn’t discourage the new recruits, who hadn’t been tasked with replacing Jones as much as staking a new claim with punk bravado. Sheppard: “With hindsight, we went out very much challenging what The Clash had done before. [At this point] we weren’t being as musical. We were very in-your-face.”

Some critics reveled in the defiant energy. After seeing the San Francisco and Santa Cruz shows, Johnny Whiteside of Beano fanzine declared, “This is The Clash, with their beauty and firepower intact, albeit bruised and scabby . . . The [absence] of Jones makes barely a shred of difference.” The Los Angeles Times’ Richard Cromelin agreed, saying Jones’s loss “hardly seems as crucial as the departure of Keith Richards would be from the Rolling Stones.”