Читать книгу Gemini - Mark Burnell - Страница 6

Marrakech

ОглавлениеThe first time I came to Marrakech I was a French tourist. I was also one half of a couple in love. Or so it must have seemed to those who saw us together. He was a lawyer from Milan, who told me that he’d been married but was now divorced. He never mentioned his second wife, though, or that she still considered their marriage idyllic, blessed, as it was, with three children, a house by Lake Como and a villa in Sardinia. Then again, I never mentioned that I intended to steal Russian SVR files from the wall-safe in his company apartment in Geneva. Or that having an affair with me might cost him his life.

Dishonesty was the blood that surged through the veins of our brief relationship. Without it there would have been no relationship. Without dishonesty I can never have a relationship because, after the truth, who in their right mind would have me?

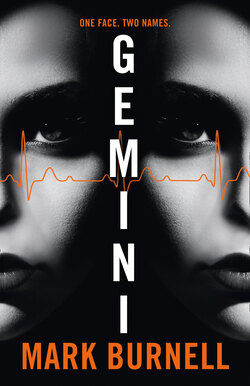

The lawyer from Milan knew me as Juliette. The man who will meet me on the roof terrace of Café La Renaissance in seven minutes will know me as Petra Reuter. Around the world my face has many names, none of them real. Long ago, when I was a complete person – a single individual – I was someone called Stephanie Patrick. But almost nobody remembers her now.

Sometimes, not even me.

Dressed in black cotton trousers, a navy linen shirt and a pair of DKNY trainers, Petra Reuter crossed Avenue Mohammed V and took the lift to Café La Renaissance’s roof terrace, which overlooked Place Abdel Moumen ben Ali. Sprawled before her, Marrakech shimmered in the parching heat; eleven in the morning and it was already close to forty centigrade. She took off her sunglasses, swept long, dark hair from her eyes and was forced to squint. Above her the sky was deep sapphire, but the horizon remained bleached of colour. Beneath her, drowsy in the scorching breeze, the city murmured: the rasp of old engines, the squeal of a horn, of a shuddering halt, the bark of a dog from a nearby rooftop. She was surprised how much green there was among the terracotta and ochre, full trees throwing welcome shade onto baking pavements. She put her sunglasses back on.

There were some tables on the roof terrace with cheap metal chairs, their turquoise paint chipped and faded. At one table two soft, pear-shaped women were hunched over a map. Petra thought they sounded Canadian. At another table an elderly man in a crumpled grey suit sat in the shade, reading an Arabic newspaper. His walnut skin was peppered with shiny pink blotches. On a section of roof terrace overlooking Place Abdel Moumen ben Ali there were three large, red plastic letters hoisted on blue poles: b – a – r. Four French tourists were taking photographs of themselves with the reverse side of the letters as a backdrop.

Petra bought a Coke and sat at a secluded table. A fortnight had elapsed since her TGV had pulled into Marseille. She’d felt uneasy on that muggy afternoon, but she felt worse now. She’d arrived in Marseille from Ostend, via Paris. In Ostend she’d gone to the bar where Maxim Mostovoi had once been a regular. A charmless place with bright overhead lights and two dilapidated pool tables, one with a torn cloth. With a shrug of regret the proprietor said that Mostovoi hadn’t been in for at least six months; the traditional first line of defence. But Petra had come prepared, and a phrase contained within a question yielded an address in Paris: an apartment on the Rue d’Odessa in Montparnasse which, in turn, led to Marseille. From Marseille she’d travelled to Beirut, then Cairo. In Cairo two addresses – a Lebanese restaurant on Amman Street in Mohandesseen and a contemporary art gallery on Brazil Street in Zamalek – had finally delivered her to this rooftop terrace in Marrakech.

With each city, with each day, her suspicion hardened: that she was no closer to Mostovoi than she had been in Ostend. Or even in London, for that matter. Not that it made much difference. The pursuit might be pointless, but she knew that she would not be allowed to abandon it.

‘Petra Reuter.’

He’d lost weight. His hair was long, lank and greasy, greying at the temples. The whites of his bloodshot eyes were a sickly yellow, his skin waxy and loose. His red T-shirt hung limply from his skeletal frame, dark sweat stains marking points of contact. Creased linen trousers were secured by a purple tie threaded through the belt-loops. His fingers were trembling. Through cigarette smoke, Petra smelt decay.

She had only met Marcel Claesen twice before. The last time had been in a dacha outside Moscow. That had been less than two years ago, but the man in front of her appeared ten years older.

‘You look sick.’

‘Nice to know you haven’t lost your charm, Petra.’

‘Do you want to know what I really think?’

His feeble smile revealed toffee-coloured teeth. ‘It must be the water here. Or the food, maybe …’

‘Or the heat?’

He missed the subtext and shrugged. ‘Sure. Why not?’

‘What are you doing here?’

They sent me to make contact with you.’

Claesen, the Belgian intermediary. That was what he had been the first time they met. Then, as now, he’d radiated duplicity. He was a man who materialized in unlikely places for no specific reason, a man who didn’t actually do anything. Instead, he simply existed in the spaces between people. A conduit, Claesen was the stained banknote that hastened a seedy transaction.

He sat down opposite her and crossed one bony leg over the other. ‘Mostovoi thought it would be better to have a familiar face. You know, someone you could trust …’

Petra raised an eyebrow. ‘So he thought of you?’

He wiped the sweat from his brow with the heel of his hand, then shook his head and attempted another smile. ‘The things I’ve heard about you, Petra. They say you killed Vatukin and Kosygin in New York. They say you killed them for Komarov.’

‘How exciting.’

‘Others say you killed them for Dragica Maric. That the two of you are in love, each of you a reflection of the other.’

‘How imaginative.’

‘How true?’

‘You’d like that, wouldn’t you? The idea of me and another woman. Especially a woman like her.’

Claesen’s shrug was supposed to convey indifference but his eyes betrayed him. ‘You mean, a woman like you, don’t you?’

A black Land Cruiser Amazon with tinted windows was waiting for them at the kerb. Petra sat in the back, keeping Claesen and the driver in front of her. They headed for Palmeraie, to the north of the city centre, where extravagant villas were secreted in secure gardens. Most of the properties belonged to wealthy Moroccans, but in recent years there had been an influx of rich foreigners. At one of the larger walled compounds the driver pulled the Land Cruiser off the tarmac onto a dirt track. Ahead, heavy electric gates parted. Above them, two security cameras twitched.

Outside the compound the ground had been arid scrub between the palm trees. Inside it was lush lawn. Sprinklers sprayed a fine mist over the grass. Men tended flowerbeds, their backs bent to the overhead sun. On the right there were two floodlit tennis courts and a large swimming pool with a Chinese dragon carved from stone at each corner.

The villa was centrally air-conditioned and smelt like an airport terminal. There were two armed men in the entrance hall. Both were fair-skinned, their faces and arms burnt bright red. One carried a Browning BDA9, the other a Colt King Cobra. Without a word they led Claesen and Petra down a hall, the Belgian’s rubber soles squeaking on the veined marble floor. The room they entered had a thick white carpet, four armchairs – tanned leather stretched over chrome frames – positioned around a coffee table with a bronze horse’s head at its centre and, in one comer, an enormous Panasonic home entertainment system. Wooden blinds had been lowered over the windows. A curtain had been three-quarters drawn across a sliding glass door that opened onto a covered terrace. The door was partly open, allowing some natural air to infiltrate the artificial. Beyond the terrace she saw orange trees, lemon trees and perfectly manicured rose beds.

‘That’s far enough.’

He was sitting on the other side of the room, his back to the source of partial light, a man reduced to silhouette. Dark trousers, a white shirt, open at the neck, dark sunglasses. Petra was surprised he could even see her.

‘You want something to drink? Some tea? Or water?’

‘Nothing.’

There were two men to his right. The shorter and leaner of the two had a bony face like a whippet: a mean mouth with thin lips, a pointed nose, sharp little eyes. His hands were restless but his gaze was steady, never leaving her. With Claesen and the pair behind her, the men numbered six, two of them definitely armed.

‘Where’s Mostovoi?’

The man in the chair said, ‘Max has been detained.’

‘Detained?’

Incorrectly, he thought he detected anxiety in her tone. ‘Not in that sense of the word.’

‘I’m not interested in the sense of the word. If he’s not here, he’s not here.’

‘He sent me instead.’

‘And you are?’

‘Lars. Lars Andersen.’

Her eyes had adjusted to the lack of light. Andersen had short, dark, untidy hair, prominent cheekbones and olive skin that was lightly pockmarked; a Mediterranean look for a Scandinavian name, Petra thought.

‘No offence, Lars, but I don’t know you.’

‘You don’t know Max, either.’

‘I know what business he’s in. Which is why I’m here. But I’m starting to think I made a mistake. I’m running out of patience. That means he’s running out of time. It’s up to him. There are always others. Harding, Sasic, Beneix …’

‘They’re not as good.’

‘As good as what? A man who never shows? What could be worse than that?’

Andersen appeared surprised by her contempt. He glanced at the short one and said, in Russian, ‘What do you reckon, Jarni? Not bad, huh?’

‘Not bad.’

‘You think she could play for Inter?’

‘No problem.’

‘Where?’

‘Anywhere, probably. That’s what I hear.’

Also in Russian, Petra said, ‘What’s Inter?’

Raised eyebrows all round. Andersen said, ‘You speak Russian?’

‘Judging by your accents, better than either of you.’

Andersen grinned. ‘Max said we should be careful with you. Watch out for her, he told us, she’s full of surprises.’

Outside, a lawnmower started, its drone as nostalgic as the scent of the grass it cut. It reminded her of those summer evenings when her father, back from work, would mow their undulating garden. A childhood memory, then. But not Petra’s childhood. The memory belonged to someone else. Petra was merely borrowing it.

‘What’s Inter?’ she asked again.

‘You don’t know?’

‘Should I?’

He shrugged. ‘Inter Milan.’ When she made no comment, he returned to English. ‘You’ve never heard of Inter Milan?’

She shook her head.

‘The football team?’

The name was faintly resonant but she said, ‘I have better things to do with my time than watch illiterate millionaires kissing each other.’

‘Inter is more than a football team.’

‘Is there any danger of you straying towards the point?’

Andersen looked as though he wished to continue. He leaned forward and opened his mouth to speak – to protest, even – but then appeared to change his mind. An awkward silence developed. Petra sensed Claesen squirming behind her.

Eventually, Andersen said, ‘Tomorrow morning, the Mellah.’

‘Mostovoi will be there?’

‘Someone will be there. They’ll take you to him.’

‘If he’s not there I’m going home.’

‘Place des Ferblantiers at ten.’

The Land Cruiser drove her back to the city centre and came to a halt on Avenue Hassan II, just short of the intersection with Place du 16 Novembre. Claesen turned round. An inch of ash spilled down his red T-shirt. His creepy confidence had returned the moment they left the walled compound.

‘Until next time, then?’

‘How did they know that you knew me?’

‘I have no idea.’

‘You didn’t ask?’

‘I received a message, an air ticket and the promise of dollars.’

‘And that was enough for you? It never occurred to you to check it out first?’

His reply was bittersweet. ‘These days that’s a luxury I can’t afford.’

‘You know something, Claesen, I’m amazed you’ve made it this far.’

‘Me too.’ Smiling once more, he waved his Gitanes at her. ‘I used to think I’d never live long enough to die from lung cancer. Now I’m beginning to think I have a chance.’

The Hotel Mirage on Boulevard Mohammed Zerktouni was in the Ville Nouvelle, not far from Café La Renaissance. Mid-range, it mostly catered for European tourists. Which was precisely what Petra was: Maria Gilardini, a single Swiss woman, aged twenty-nine. A dental hygienist from Sion.

There was a message for her at reception. She took the envelope up to her room, at the rear of the building, overlooking a small courtyard, opposite the back of an ageing office block. She sat on the bed and opened the envelope. As expected, there was nothing inside.

Petra had heard of Maxim Mostovoi long before he became a contract. A former air force pilot, he’d emerged from the rubble of the Soviet Union with his own aviation business. His military career had been restricted to cargo transport. At the time, that had been a source of regret. Later it proved to be the source of his fortune.

Among the first to recognize potential markets for the Soviet Union’s vast stockpile of obsolete weaponry, Mostovoi was able to commandeer cargo aircraft from what remained of the Soviet air force. Then he formed partnerships with contacts in the army who were able to supply him with arms. In the early days he based himself in Moscow, taking comfort from the chaos that bloomed in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union. There were few laws to contain him. Those that existed were not enforced; bribery tended to ensure that. Failing bribery, there was always violence.

Mostovoi’s first fortune was made in Africa. Rebel factions sought him out, eager for cheap weapons. Using huge Antonov cargo aircraft, he delivered to Rwanda, Angola and Sierra Leone, frequently taking payment in conflict diamonds, depositing the gems in Antwerp. Soon Mostovoi decided he would prefer to be closer to them. In 1994 he moved to Ostend, establishing an air freight company named Air Eurasia at offices close to the airport. As his reputation grew, so did demand for his services. He established an office in Kigali, the Rwandan capital, at the height of the genocide perpetrated by the Hutu militia. He bought a hotel in Kampala, in neighbouring Uganda. The top floor was converted into a luxury penthouse, marble flown in from Italy, bathrooms from Scandinavia, hookers from Moscow. Twice a year Unita rebels travelled from Angola to the hotel in Kampala with pouches of diamonds. The stones were valued by Manfred Hempel, a leading Manhattan diamond merchant, who was extravagantly rewarded for his time. Despite this, Hempel hated the trips to Uganda. To ease his discomfort Mostovoi used his Gulfstream V to ferry the diamond dealer directly from New York to Kampala and back again.

By 1996 his fleet of aircraft, mostly Antonovs and Illyushins, had grown to thirty-eight and had attracted the attention of the Belgian authorities. In December of that year he relocated Air Eurasia to Qatar, opening associate offices in Riyadh and the emirates of Ras al Khaimah and Sharjah. In February 1997 he met senior representatives of FARC – the Colombian rebel army – at San Vicente del Caguan, but failed to come to an agreement. From Colombia he travelled directly to Pakistan. In Peshawar he struck a deal to supply weapons to the Taliban in Afghanistan. Here he was paid in opium, which he sold for processing and onward distribution in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Born in Moscow in 1962, Mostovoi had been destined for mediocrity. An unexceptional pupil, a poor athlete, he longed to fly fighters for the Soviet air force but lacked the necessary skills, and was thus relegated to the cargo fleet. To those who knew him best, this would have seemed entirely predictable. As charming and amusing as he could be, it was accepted by everybody that Max would never amount to much. His wife used to tease him in public, and all Mostovoi would muster in his defence was a resigned shrug. Still, a decade and two hundred million dollars later, the memory of his heavy-hipped ex-wife had been eclipsed by the finest flesh money could buy. As a younger man he’d often dreamed of taking his revenge upon those who had humiliated him over the years. Now that he was in a position to do so, he found he couldn’t be bothered. He didn’t have the time. It was enough to know that he could.

Petra knew that had Mostovoi been content to confine his business interests to Africa, he would never have become the subject of a contract. The reality was that nobody cared about Africa. Afghanistan, however, was different. Through his relationship with the Taliban, Mostovoi was connected to al-Qaeda. Before 11 September 2001 he’d been an easy man to find, confident of his own security, keen to expand his empire. Since that date he’d been invisible.

Dusk descended quickly upon Djemaa el-Fna, the huge square in the medina that was the heart of Marrakech. Kerosene lamps replaced the daylight, strung out along rows of food stalls.

Petra found the café on the edge of the square. The outdoor tables were mostly taken. Inside, she picked a table with a clear view of the entrance. A slowly rotating fan barely disturbed the hot air. To her right, beneath an emerald green mosaic of the Atlas mountains, two elderly men were in animated discussion over glasses of tea.

She ordered a bottle of mineral water and drank half of it, checking the entrance as often as she checked her watch. At ten past seven she got up and asked the man behind the bar for the toilet. Past the cramped, steaming kitchen she came to a foul-smelling cubicle, which she ignored, pressing on down the dim corridor to the door at the end, which was shut. She tried the handle and it opened, as promised. She found herself in a narrow alley, rubble underfoot. At the end of the alley she saw the lane that she’d identified on the town map. She unbuttoned her shirt, took it off, turned it inside out and put it back on, trading powder blue for plum.

At twenty-five past seven she emerged from a small street on the opposite side of Djemaa el-Fna to the café. This time she melted into the crowd at the centre of the square, trawling the busy stalls, until she found one with no customers. She sat on a wooden bench beneath three naked bulbs hung from a cord sagging between two poles. The man on the other side of the counter was tending strips of lamb on an iron rack, fat spitting on the coals, smoke spiralling upwards, adding to the heat of the night. Petra passed fifteen dirhams across the counter for a small bowl of harira, a spicy lentil soup.

The woman appeared within five minutes, a child in tow. Short, dark and squat, she wore a dark brown ankle-length dress and a flimsy cotton shawl around her shoulders. The child had black curls, caramel skin, pale hazel eyes. She was eating dried fruit. They sat on the bench to Petra’s right. The woman ordered two slices of melon, which the man retrieved from a crate behind him.

In French, she said, ‘Someone was in your hotel room today. A man.’

Petra nodded. ‘What was he doing?’

‘Looking.’

‘Did he find anything?’

‘It’s not possible to say. He spent most of his time with your laptop. I think he might have downloaded something. It wasn’t easy to see. The angle was awkward.’

‘From across the courtyard?’

The woman shook her head. ‘That view was too restricted. I had to try something else. A camera concealed in the smoke detector.’

‘I hadn’t noticed there was a smoke detector.’

‘Above the door to your bathroom. It’s cosmetic. A plastic case to satisfy a safety regulation. Actually, I’m surprised. A bribe is easier and cheaper.’

‘Where was the base unit?’

‘Across the courtyard. In the office.’ The woman finished a mouthful of melon. ‘He went through your clothes, your personal belongings. He took care to replace everything as he found it. He searched under the bed, behind the drawers, on top of the cupboard. All the usual hiding places. You have a gun?’

‘Not there. Anything else?’

‘A Lear jet arrived at Menara Airport early this morning. A flight plan has been filed for tomorrow afternoon. Stern wants you to know that Mostovoi has a meeting in Zurich tomorrow evening.’

I lie on my bed, naked and sweating. When I came to Marrakech with Massimo, the lawyer from Milan, we stayed at the Amanjena, a cocoon of luxury on the outskirts of the city. There we indulged ourselves fully. On our last evening we ate at Yacout, a palace restaurant concealed within a warren of tiny streets. We drank wine on the roof terrace while musicians played in the corner. A hot breeze blew through us. Mostly, I remember the view of the city by night, lights sparkling like gemstones against the darkness. Later we ate downstairs in a small courtyard with rose petals on the floor. That was where Massimo took my hand and said, ‘Juliette, I think I’m falling in love with you.’

I gazed into his eyes and said, ‘I feel it, too.’

I think he was telling the truth. At the time, that never occurred to me because everything I said to him was a lie and I assumed we were both playing the same game. When he said we should meet again in Geneva I said that would be lovely, that I couldn’t wait. Which was as close to the truth as I ever got with Massimo; I needed unforced access to his company apartment. Later, when he told me he thought I looked beautiful, I just smiled, as I wondered whether I would be the one to kill him. As it turned out, it was somebody else: Dragica Mark.

When Claesen mentioned her name, the memory of the last time we were together was resurrected: about two years ago, at the derelict Somerset Hotel on West 54th Street in Manhattan. We were in a narrow service corridor down one side of the hotel. It was dark and damp, the sound of the city barely audible over the rain. She was armed with a Glock. She told me to kneel. There was nothing I could do but obey. Then she asked me questions, which I answered honestly. Certain that I was about to die, there had seemed little point in lying. Finally she fired the Glock. Above my head. By the time I realized I was still alive, she was gone.

Place des Ferblantiers, ten in the morning. Petra’s guide wore the traditional white djellaba with a pointed hood. Inside the Mellah, the Jewish Quarter, they entered a covered market. In the still heat, smells competed for supremacy: fish, body odour, chickens, rubbish and, in particular, a meat counter with oesophagi hanging from hooks. The hum of flies was close. Beyond the market the guide led her through a maze of crooked streets, some so narrow she could press her palms against both walls. There were no signs and no straight lines. They passed doors set into walls, snatching occasional glimpses: a staircase rising into darkness, a moving foot, a sleeping dog. Lanes were pockmarked with tiny retail outlets: a man selling watch straps from a booth the size of a cupboard, a shop trading in solitary bicycle wheels, Sprite and Coke sold from a coolbox in the shallow shade of a doorway.

They came to an arch. Beneath it a merchant was arranging sacks of spices. Behind the sacks, on a wooden table, were baskets of lemons and limes. Garlands of garlic hung from a wooden beam. They passed through the arch into a courtyard. Beneath a reed canopy two women were weaving baskets.

They headed for a door on the far side of the courtyard, took the stairs to the upper floor, turned left and arrived at a large, rectangular room. It was carpeted, quite literally: carpets covering the floor and three walls. Other carpets were piled waist high, some exquisitely intricate, with silk thread shimmering beneath the harsh overhead lighting, others a cruder style of kilim, in vivid turquoise, egg-yolk yellow and blood red. The fourth wall contained the only window, which looked out onto the courtyard.

Maxim Mostovoi was at the far end of the room, sprawled across a tan leather sofa as plushly padded as he was. He wore Ray-Ban Aviator sunglasses and a full moustache. His gut stretched a pale green polo-shirt that bore dark sweat stains in the pinch of both armpits. Fat thighs made his chinos fit as snugly as a second skin.

Jarni, the whippet-faced man from the villa at Palmeraie, stood to Petra’s right. Beside him was a taller man, a body-builder perhaps, massive shoulders tapering to a trim waist, black hair oiled to the scalp, his skin the colour and texture of chocolate mousse. He had a gold ring through his right eyebrow.

‘I feel I know you,’ Mostovoi murmured.

‘A common mistake.’

‘I’m sure.’ He nodded at the body-builder. ‘Alexei …’

Petra said, ‘I’m not armed.’

‘Then you won’t mind.’

Petra had been frisked many times. There were two elements to the process that almost never varied, in her experience: the procedure was carried out by men, and they took pleasure in their work. More than once she’d had eager fingers inside her clothes, even inside her underwear and, on one occasion, inside her. The man who’d done that had gorged himself on her discomfort. Later, when she crushed both his hands in a car door, she took some reciprocal pleasure from the act.

‘You should be more careful where you put your fingers,’ she’d told him, as he surveyed what remained of them.

Petra had dressed deliberately. Black cotton trousers, a black T-shirt beneath a turquoise shirt tied at the waist and a pair of lightweight walking boots. Suspended from the leather cord around her neck was a fisherman’s cross made of burnished mahogany, the wood so smooth that the fracture line at the base of the loop was almost invisible. She wore her long dark hair in a pony-tail.

Among friskers she’d known, Alexei the bodybuilder was about average. In other words, tiresomely predictable. Petra knew that behind his sunglasses Mostovoi wasn’t blinking. His face was shiny with sweat. As he took in the show, she took in the room. Apart from his mobile phone, the table was bare. A lamp without a shade stood on an upturned crate at the far end of the sofa. By the door she’d noticed a box containing a wooden paddle for beating the dust from carpets. Next to the box there was a portable black-and-white security monitor on a creaking table, a bin, a ball of used bubble-wrap and an electric fan, unplugged. She’d been in rooms that offered less. And in situations that threatened more. Until now she hadn’t known whether Mostovoi would be viable.

Alexei reached between her legs, but Petra snatched his wrist away. ‘Take my word for it, you won’t find an Uzi down there.’

He glanced at Mostovoi, who shook his head, then continued, skipping over her stomach and ribs before slowing as he reached her breasts. His fingers found something solid in the breast pocket of her shirt. Petra took it out before he had the chance to retrieve it himself.

‘What’s that?’ Mostovoi asked.

‘An inhaler,’ Petra said. ‘With a Salbutamol cartridge. I’m asthmatic’

He was surprised, then amused. ‘You?’ It was the third version of the inhaler Petra had been given. She’d never used any of them. Mostovoi’s amusement began to turn to suspicion. ‘Show me.’

‘You put this end in your mouth, squeeze the cartridge and inhale.’

‘I said, show me.’

So she did, taking care not to break the second seal by pushing the cartridge too vigorously. There was a squirt of Salbutamol from the mouthpiece, which she inhaled, a cold powder against the back of her throat.

The frisk resumed, until Alexei stepped away from Petra and shook his head. Mostovoi seemed genuinely amazed. ‘You don’t have a gun?’

‘I didn’t think I’d need one. Besides, I didn’t want your friend to feel something hard in my trousers and get over-excited.’

A barefoot boy entered the room, carrying a tray with two tall glasses of mint tea and a silver sugar bowl. Fresh mint leaves had been crushed into the bottom of each glass. He passed one to Petra and the other to Mostovoi, before leaving.

Petra said, ‘That was a neat idea, using Claesen as an intermediary yesterday.’

‘It was a matter of some … reassurance.’

‘I know.’ She caught his eye. ‘Your reassurance, though. Not mine.’

Mostovoi inclined his head a little, a bow of concession. ‘Your reputation may precede you, but nobody ever knows what follows it. Within our community you’re a contradiction: the anonymous celebrity.’

‘Unlike you.’

‘I’m a salesman. Nothing more.’

‘Don’t sell yourself short.’

Mostovoi smiled. ‘I never do.’ He lit a Marlboro with a gold Dunhill lighter. ‘This is a change of career for you, no?’

‘Not so much a change, more of an expansion.’

‘I know you met Klim in Lille last month. And again in Bratislava three weeks ago.’

‘Small world.’

‘The smallest you can imagine. You discussed Sukhoi-25s for five million US an aircraft. For fifty-five million dollars, he said he could get you twelve; buy eleven, get one free.’

‘What can I say? We live in a supermarket culture.’

‘Or for one hundred million, twenty-five. Which is not bad. But you weren’t interested.’

‘Because?’

‘Because the Sukhoi-25 isn’t good enough. The MiG-29SE is superior in every way. That’s what Klim told you. And that they can be purchased direct from Rosboron for about thirty million dollars each. However, good discounts can be negotiated, so …’

‘But not the kind of discounts that you can negotiate. Right?’

Mostovoi took off his sunglasses and placed them beside his phone. He wiped sweat from his forehead. ‘That depends. I understand you’re also in the market for transport helicopters. Specifically, the Mi-26.’

‘Actually, the Mi-26 is all I’m in the market for. Klim got over-excited. We discussed the Sukhoi and the MiG, but that’s all it was. Talk.’

Mostovoi looked disappointed.

The Mi-26 was a monster: 110 feet in length, almost the size of a Boeing 727, it was designed to carry eighty to ninety passengers, although in Russia, where most of them were in service, it was not uncommon for them to transport up to one hundred and twenty.

‘How many?’ Mostovoi asked.

‘Two, possibly three.’

‘That’s a lot of men.’

‘Or a lot of cargo.’

‘Either way, it’s a lot of money.’

‘I’m not interested in running a few AK-47s to ETA or the IRA.’

Mostovoi pondered this while he smoked. ‘Still, a deal this size … normally I would hear about it.’

‘Normally you’d be involved.’

‘True.’

‘Which would leave me on the outside.’

‘Also true.’

Petra took a sip from her tea, letting Mostovoi do the work. Casually, she wandered over to the window, which was open, and looked out. There was no hint of a cooling breeze to counter the stifling heat. The canopy covering the basket-weavers was directly below. She glanced at Alexei and Jarni. They’d relaxed; Jarni’s eyes had glazed over. The wooden grip of a Bernardelli P-018 protruded from the waistband of his trousers. Alexei was wearing a tight white T-shirt that revealed his chiselled physique to maximum effect. And the fact that he was unarmed.

The immediate future was coming into focus. She returned her attention to Mostovoi, who was talking about the nature of the clients she represented. A rebel faction of some sort, perhaps. Or drug warlords. From Colombia, maybe, or even Afghanistan.

‘What’s your point?’

‘Maybe there is no deal.’

He made it sound as though the idea had only just occurred to him. Petra felt her damp skin prickle with alarm. ‘Klim thinks there is.’

Mostovoi snorted with contempt. ‘That’s why Klim flies economy while I have a Gulfstream V …’

Petra spun to her left, sensing the movement behind her: Alexei advancing, swinging at her. The blow caught her on the ribs, not across the back of the neck, as intended. But it was enough to crush the air out of her. She tumbled onto the mustard carpet, her glass of tea shattering beneath her. Alexei came at her again, brandishing the wooden paddle like a baseball bat.

Jarni yanked the Bernardelli from his waistband. Petra rolled to her right, fragments of glass biting into her. The paddle missed her head, crunching against her shoulder and collar-bone instead. Moving as clumsily as she’d anticipated, his bubbling muscularity a hindrance, not an advantage, Alexei attempted to grasp her, but she slithered beyond his reach.

Jarni aimed a kick at her. His shoe scuffed her left thigh. She made a counter-kick with her right foot, hooking away his standing leg. He toppled backwards. As his elbow hit the ground the gun discharged accidentally, the bullet ripping into the ceiling, sprinkling them with dusty rubble.

Before she could get to her feet Alexei’s boot found the same patch of ribs as the paddle. Winded and momentarily powerless, she couldn’t prevent the bodybuilder grabbing her pony-tail and dragging her to her knees. Jarni was on his side, stunned, the 9mm a few feet away. Alexei hauled her to her feet and threw several punches, each a hammer-blow, the worst of them to the small of her back, the force of it sending a sickening shudder through the rest of her. Then he attempted to pin her arms together behind her back. Which would leave her exposed to Jarni. Or even Mostovoi. Through the fog, she understood this.

Petra curled forward as much as she could, then dug her toes into the ground and launched herself up and back with as much power as she could muster. The crown of her head smacked Alexei in the face. She knew they were both cut. His grip slackened and she wriggled free as he staggered to one side, dazed and bloody. Petra grabbed the inhaler from her breast pocket, pressed the cartridge, felt the second seal rupture and fired the CS gas into his eyes.

Jarni was on his feet now, the gun in his right hand rising towards her. With a stride she was beside him, both hands clamping his right wrist. Unbalanced, he wobbled. She drove his hand down and nudged the trigger finger. The gun fired again, the bullet splitting his left kneecap.

Gasping, Alexei was on his knees, his face buried in his hands, blood dribbling between his fingers. Jarni started to scream. And Mostovoi was exactly where he’d been a few moments before. On the sofa, not moving, the complacency of the voyeur usurped by the paralysis of fear.

There were shouts in the courtyard and footsteps on the stairs. She picked up Jarni’s Bernardelli and aimed at Mostovoi’s eyes.

Resigned to the bullet, he matched her stare.

‘Why?’

As good a last word as any, Petra supposed. She pulled the trigger.

Nothing.

Mostovoi blinked, not comprehending. She tried again. Still nothing. The weapon was jammed. And now the footsteps were at the top of the stairs and approaching the door.

She dropped the gun and took the open window, an action that owed more to reflex than decision. She shattered the fragile wooden shutters and fell. The canopy offered no resistance, folding instantly. Her fall was broken by the bodies and baskets beneath. From above, she heard a door smacking a wall, a rumble of shoes, shouts.

Instantly she was on her feet, accelerating across the courtyard towards the arch. Behind her, shots rang out. Puffs of pulverized brick danced out of the wall to her right. From another door in the courtyard two armed men emerged in pursuit. Then she was in the gloom of the arch, safe from the guns behind, but not from the threat ahead.

Even as her eyes adjusted to the shade she saw the merchant reacting to her, bending down to pick up something from behind a stack of wooden boxes. With her left hand Petra reached for her throat and tugged the cross. The leather cord gave way easily. The merchant was rising, silhouetted against the sunlight flooding the street. Her right hand grasped the bottom of the cross, pulling away the polished mahogany scabbard to reveal a three-inch serrated steel spike.

The merchant raised his revolver. Petra dived, clattering into him before he could fire. They spilled across sacks of paprika and saffron. In clouds of scarlet and gold she aimed for his neck but missed, instead ramming the spike through the soft flesh behind the jawbone up into the tongue. He went into spasm as she grabbed his revolver, clambered over him, spun round and waited for the first of the chasing pair to appear. Four shots later they were both down, and Petra Reuter was on the run again.

The Hotel Sahara was between Rue Zitoune el-Qedim and Rue de Bab Agnaou, the room itself overlooking the street. Petra closed the door behind her. Deep blue wooden shutters excluded most of the daylight. It was cool in the darkness.

There was a small chest of drawers by one wall. Petra opened the top right drawer. She’d already removed the back panel so that it could be pulled clear. She dropped to a crouch, reached inside and found the plastic pouch taped to the underside. The pouch contained an old Walther P38K, an adaptation of the standard P38, the barrel cut to seven centimetres to make it easier to conceal. She placed the gun on top of the chest of drawers.

Her pulse was still speeding and she was soaked – mostly sweat, some blood – the dust and dirt of the Mellah caking her skin.

There was a loud bang. She reached for the Walther. The bang was followed by the drone of an engine. A moped, its feeble diesel spluttering beneath her window. A backfire, not a shot, prompting a half-hearted smile.

Across town they would be waiting for her at the Hotel Mirage; Maria Gilardini’s clothes were still in her room, her toothbrush by the sink, her air ticket wedged between the pages of a paperback on the bedside table.

Petra opened the shutters a little, dust motes floating in the slice of sunlight. In the corner of the room was a rucksack secured by a padlock. She opened it, rummaged through the contents for the first-aid wallet, which she unfolded on the bed. Then she stripped to her underwear and examined herself in the mirror over the basin. Her ribs were beginning to bruise. Among the grazes were cuts containing splinters of glass.

Mostovoi had known there was no deal; not at first – he’d agreed to meet her, after all – but eventually. The more she considered it, the more convinced of it she became. He hadn’t asked enough questions about Klim to be so sure of his doubt. The fact that he’d allowed himself to be met proved that he was interested – with so much money at stake, that was inevitable – and yet he’d known. Or suspected, at least.

She used tweezers to extract the shards of glass, then dressed the worst cuts. Next she took the scissors to her hair, losing six inches to the shoulder. Not a new look, just an alteration. She put in a pair of blue contact lenses to match those in the photograph of the passport: Mary Reid, visiting from London, born in Leeds, aged twenty-seven, aromatherapist. Rather than Petra Reuter, visiting from anywhere in the world, born in Hamburg, aged thirty-five, assassin.

The hair and the contacts were useful, but Petra knew there were more significant factors in changing an identity; deportment and dress. When Mary Reid moved, she shuffled. When she sat, she slouched. The way she carried herself would allow her to vanish in a crowd. So would the clothes she wore, and since Mary Reid was on holiday they were appropriate: creased cream linen three-quarter-length trousers, leather sandals from a local market, a faded lilac T-shirt from Phuket, a triple string of coral beads around her throat.

She abandoned the rucksack and the Walther P38K, taking only a small knapsack with a few things: some crumpled clothes, a wash-bag, a battered Walkman, four CDs, a Kodak disposable camera and a book. Even though her room was pre-paid, she told no one she was leaving. She caught a bus to the airport and a Royal Air Maroc flight to Paris. At Charles de Gaulle she checked in for a British Airways connection and then made a call to a London number.

Flight BA329 from Paris touched down a few minutes early at ten to ten. By ten past, having only hand-luggage, she was clear of Customs. The courier met her in the Arrivals hall. He was pushing a trolley with a large leather holdall on it. She placed the knapsack next to the holdall and they headed for the exit.

‘Good flight?’

‘Fine.’

‘Debriefing tomorrow morning. Eleven.’

At the exit Petra picked up the leather holdall and the man disappeared through the doors with her knapsack. She turned back and made for the Underground. As the train rattled towards west London she opened the holdall. Her mobile phone was in a side pocket. She switched it on and made a call. When she got no answer she tried another number.

She knew it was unprofessional, but she didn’t care. She was tired, she was hurt, what she needed was rest. But what she wanted was something to take away the bitter taste.

After the call she went through the holdall: dirty clothes rolled into a ball – her dirty clothes – and another wash-bag, again hers. In another side pocket she found credit cards, her passport and some cash: a mixture of euros, sterling and a few thousand Uzbek sum. There was a Visa card receipt for the Hotel Tashkent and an Uzbekistan Airways ticket stub: Amsterdam-Tashkent-Amsterdam. In the main section of the holdall there was a plastic bag from Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, a bottle of Veuve Cliquot inside, complete with euro receipt.

Much as it hurt her to admit it, she admired their craft. If nothing else, they were thorough.

At the bottom of the bag was a digital voice recorder with twenty-one used files in two folders. Also a Tamrac camera bag containing six used rolls of Centuria Super Konica film, a Nikon F80, a Sekonic light meter, three lenses and a digital Canon. She knew what was on the Canon and the rolls of film: details from the Fergana valley, home to an extremist Uzbek Islamic militia.

At Green Park she swapped from the Piccadilly Line to the Victoria Line, and at Stockwell from the Victoria Line to the Northern Line. From Clapham South she walked. It took five minutes to reach the address, which was sandwiched between Wandsworth Common and Clapham Common, a street of large, comfortable semi-detached Victorian houses. Volvos and Range Rovers lined both kerbs.

Karen Cunningham let her in. They kissed on both cheeks, hugged, left the holdall in the hall and made their way through the house to the garden at the rear. A dozen people sat around a wooden table. Smoke rose from a dying barbecue in a far corner of the garden.

‘Stephanie!’

Her fourth name of the day.

From the far side of the table Mark was coming towards her. He wore the collarless cotton shirt she’d bought for him, the sleeves rolled up to the elbow. They kissed. She noticed he was barefoot.

They made space for her at the table. Someone poured her a glass of red wine. She knew all the faces in the flickering candlelight. Not well, or in her own right, but through Mark. After the welcome the conversation resumed. She picked at the remains of some potato salad as she drank, content not to say too much. Gradually the alcohol worked its temporary magic, purging her pain. Purging Petra.

From Marrakech to Clapham, from Mostovoi to these people, with their careers, their children, their two foreign holidays a year. From a steel spike to a glass of wine, from one continent to another. Two worlds, each as divorced from the other as she was from any other version of herself.

It was after midnight when Mark leaned towards her, frowning, and said, ‘It’s not the hair. It’s something else …’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘There’s something … different about you.’

‘You’re imagining it.’

He shook his head. ‘Got it. It’s your eyes.’

For a moment there was panic. Then came the recovery, complete with a playful smile, while the lie formed. ‘I was wondering how long it would take you to notice.’

‘They’re blue.’

‘Coloured lenses. Found them in Amsterdam. Pretty cool, don’t you think?’