Читать книгу The Story of Looking - Mark Cousins - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

LOOKING, SELF, HOME AND DESIGN: THE THINGS NEARBY

LET’S imagine, now, that we are looking through the eyes of a four-year-old. As an infant she began by seeing blurs in black and white. She then saw distance, colour, other people, emotions and nature.

This chapter sees an expansion of her seeing. The things that are close by, within arm’s reach, begin to mean more to her. They furnish her world. She sees objects and her home, and the people immediately around her. She looks at how those people interact with each other, and sees that some of them make more decisions and have more power than others. She starts to understand social context and function. When she looks she sees how things fit together. She stitches images together to make composites.

LOOKING AND ME

For the child, the things which are closest to her – other human beings – will begin to form a visual network. She will notice where they are in relation to each other, how their movements and patterns repeat. It is like the girl in the middle of this painting by Sofonisba Anguissola. Anguissola was born in the 1530s, had five sisters, was admired by Michelangelo, and lived into her nineties.

Here she paints three of her sisters dressed in brocade and pearls, overlooked by a maid as they play chess, which at the time was thought of as a man’s game. The youngest, Europa, enjoys how her sister on the right seems to call for the attention of the third sister, on the left, who looks at us. Our interest here is in those looks. Europa is in the middle of a network of them. We can imagine her head turning, her eyes darting between her sisters, taking in their expressions and noticing how they react to each other.

She is perhaps too young to follow the game, or understand much of what was happening in 1555 on the continent after which she was named, but she is drinking-in human interactions. She is getting a sense of where she is in the world. We glimpse the wider world behind her, and her eyes will of course have run out along that z-axis too, and she will have a sense that the maid is part of the family but on a lower level and less well dressed, so will have begun to see social structures. Will she have noticed yet that the maid is less happy than the sisters, and more anxious because more charged with responsibility?

Imagine now that Europa is not a privileged sixteenth-century Italian girl, but an old Indian man, hunkered down at a busy crossroads in Kolkata. It is dawn. The city’s flower sellers are laying out their huge baskets of yellow blooms and saffron. Young men on bicycles whizz by, bringing cloth to markets. The sun is still low and cows kick dust up into its beams, so that they become shafts of light. People are everywhere. Mechanics open up garages to begin their day’s work. Someone welds with an oxyacetylene torch. The old man is going nowhere, so takes in the scene. He hears many things, of course, but he sees the face of a flower seller and for a moment imagines her home life. Then his eye is caught by one of the cyclists (who, as we have seen, does not seem to blur, despite moving fast) and he is reminded of his own son. Then the mechanic talks to the welder and the old man imagines what each is saying to the other. The flowers and sunlight give colour, the dawn adds sfumato, there is emotion on the flower seller’s face – she is old and seems arthritic. What complex looking the man is doing. Mostly, he is people-watching, like Europa was people-watching, like we people-watch when we are at train stations. His network of glances give him pieces of a visual jigsaw puzzle, which he assembles to create not only a street scene, but a reading of that scene involving educated guesses about the status and inner lives of the people he sees.

Like the old man, Europa is building her visual world, its physical and human spaces. At the centre of it is herself. The earliest humans saw themselves reflected in water, and there have been mirrors since at least the Bronze Age. In ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, the most visual of written languages, ankh, the sign for life, was also the word for mirror. A child’s fascinated encounter with its own image in a mirror has been much discussed in psychoanalysis, and most people will look at themselves regularly throughout their lives, more so in the ages of photography and digital.

What do they see? In a mirror, our heads are exactly half the size they are in real life, but we do not notice the smallness because seeing ourselves outside ourselves, as an object in the world, is stranger than the mirror’s optical illusion. The billions of selfies now taken happen because of the fun of seeing ourselves from outside our own visual cortex, in space and time, with our friends or in a famous place. Painters have been particularly good at looking at themselves. Their self-portraits reveal the obsessiveness, neurosis, ego and pathos of being alive. Van Gogh and Rembrandt used their own faces to chart their anguish and ageing. This self-portrait by the French painter Gustave Courbet is sometimes called The Desperate Man, but perhaps more than desperation, it is possible to see in it the shock of catching sight of yourself.

He pulls his hair back and seems to say, Is that really me? He was about twenty-four when he stared at himself to paint it, and would live for more than three decades after this, but his picture registers his fascination with the Big Bang of himself.

In comparison, the German artist Albrecht Dürer, who was only a few years older than Courbet when he did this painting, is way beyond the shock of self.

He did a remarkable pencil sketch of his right profile when he was thirteen, the first of many self-portraits (including a naked one), and he is perhaps the first artist ever to have his own logo – the famous ‘AD’, on the left of this painting. This is a man who is very comfortable with looking at himself and seems to see Jesus Christ in his geometric symmetry, handsome stillness and almost sculptural confidence. There is no flicker here, no rush to the canvas like Courbet’s. As did many, Dürer thought that the Day of Judgement would come in 1500, so when it did not, he perhaps felt that he had to reimagine himself on a longer timeline. He is seeing himself as a god: the self-portrait as an act of love. The word mirror comes from mirari in Latin, which means ‘to marvel at’.

Like Dürer, Egon Schiele painted himself often. He is usually naked in the sketches, and they have a dash about them. He drew rapidly, lifting the pencil from the paper as little as possible, then often coloured around the figure, making it look thinner still than its whippet proportions. The self he saw in the mirror was attenuated.

Often, as here, the darkest things in his watercolours are the eyes and genitals. They look at each other. The body is just the skeletal, angular, runway in between. The fingers, like Dürer’s, are long and bony. Schiele was bad at everything in school apart from art and sport, the body and the line. His short active years as an artist (he died, aged twenty-eight, in 1918) coincided with the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the rise to prominence of his fellow Austrian Sigmund Freud. Sexuality was surfacing. Human beings were being figuratively unclothed, their social pretences stripped away. When Schiele looked at himself, he undressed. He removed the old varnish of empire as if to say We have been hiding, behind our hands, as here, like the child who thinks she disappears when she covers her eyes, but also behind our old-world, nineteenth-century, uniformed bourgeois rationalism. Schiele was not edified by what he saw, but was compelled to look.

The same is true of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. In this picture from 1932, she stands on a plinth on the border between Mexico and the United States.

At first glance it seems that the smoke, factories and skyscrapers on the right show the America she hated, and that the flowers and cacti, ancient sculpture, pyramid and electric spark between Sun and Moon on the left are symbols of the elemental Mexico that she preferred. She even holds the Mexican flag. But the painting is not nearly so binary. Kahlo was a modernist and leftist, so she was not averse to smoke stacks. It says FORD on them, and she had just had a miscarriage at the Henry Ford clinic, so the image starts to seem as much about personal loss as nation. The stoves on the right almost look like cannons which could have fired the skull or stones piled on the left. They are lined up like the flowers, and the sun has its echo in the orange heater in the bottom right.

What is striking is how Kahlo – or Carmen Rivera, as she signs herself on the plinth, using her husband’s name – plants herself so squarely into this nation-dream. Everything is within touching distance. It is an image of the proximate. Anguissola set Europa into a network of glances. Kahlo, here, is presenting the Mexico she has seen and the America she has seen, the two societies she is torn between, and has herself rise above them, once on the plinth, a second time by showing us the ground underneath it. Artists like Kahlo, Dürer and Schiele or, later, Joseph Beuys or David Bowie, show that to look at yourself, and so consider your place in the world, is to see something hidden, surreal (which we will come to later) and even mythic. For the looker, the self is the most available object in the world. It is inescapable, a thing that contains looking and interacts with other lookers.

LOOKING AT HOME

Homes are extensions of selves, exoskeletons that shelter and express. They are where we look from. So far in our story we have been mostly outdoors. Now we build a cocoon around ourselves and, suddenly, we make a new distinction between in and out, here and there, safe and unsafe.

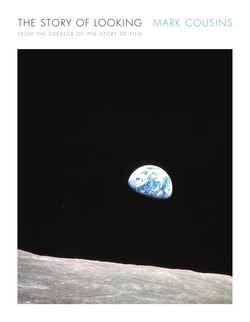

The first image in this book looks out into the dawn from the shelter of a home. As we build our sense of the looked-at life, it is time to imagine our early lookers in their homes. Caves at first, but then structures built of mud, wood, stone, brick, concrete, steel or glass. What kind of looking do homes allow us to do?

Consider this image, from the Soviet film-maker Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1975 film Mirror.

The first thing we notice is that the home creates darkness, an opaque enclosure. Looking needs light, but homes exclude light. We are inside, already here, rooted. The hunter-gatherers have stopped, and have been here some time; the floorboards are well worn. Inside the home, the children we see will have looked at each other, their family, the table on which food is served, and so forth. Most still life paintings in the history of art capture such looking – the half-peeled lemons in the pictures of Dutch artist Willem Kalf, the peel dangling over the edge of a table which is covered with a damask cloth. Édouard Manet’s bunch of asparagus, quickly painted, is less showy than Kalf’s lemons: it is not trying to be elegant or posh. The asparagus is just there, to capture the way it lies. In the Tarkovsky image (shot by Georgi Rerberg) a bunch of flowers, something to make the indoors more visual, sits on the table.

This second-century Roman mosaic, known as Unswept Floor, has removed everything thematic or visual that is not about the simple pleasure of indoor looking. We do not see the people or the food table, but what has fallen from it. It is as if someone yanked the tablecloth in a still life.

This is underneath, domestic looking. We see secrets here. A house is full of visual secrets. There is even a mouse nibbling on a nut. In his book The Poetics of Space, philosopher Gaston Bachelard says that our home is our corner of the world, seized upon by our imaginations. It is nested looking. A home is a nest which is contained within larger nests – villages, cities and nations.

In the Tarkovsky image, home is seized upon by his imagination. The camera is not under a table, but is inside. There is a security to the image. We are not exposed, we are not outside trying to get in. We are looking at the children, who in turn look outside. Doors and windows as eyes of sorts. The kids are like Caspar David Friedrich’s man on the mountain top, staring across the misty hills. Again there is a mythic dimension: in Tarkovsky’s image the home is womb-like, a haven, the place where our living starts, our looking starts. It is a harbour image. The sea will be rougher beyond the harbour.

At first glance it seems to have little in common with this image of a home, from Early Summer by Yasujiro Ozu, whose image of red flowers against a green fence we considered earlier.

This home does not exclude light. We can see everything. And where Tarkovsky’s image was high contrast, this one is mostly mid tones, shades of grey. Yet this home invites looking even more than the previous one. The image is rigorously composed of squares within squares. Including its outer edge, we can count five concentric frames. The camera is at kneeling height. A dozen verticals are balanced by a dozen horizontals. Tonality and composition give the scene great equilibrium. Add in the fact that Ozu and cinematographer Yûharu Atsuta have used a long lens to flatten the image and we have the sense that they are trying to deny the z-axis, that mythic departure that the Tarkovsky image evokes.

The fact that the image seems to hold the women within it, rather than encourage them to leave it, resonates in the film and for the theme of looking and home. The woman on the right is Noriko, a twenty-five-year-old whose family thinks she should be married by now, and so has found her a suitor. Their sense of how a woman’s life must unfold in Japan means that she should not still be in the family home. She should be looking for a man and to the future and at her own home. Noriko, however, gently and with good humour, rejects their plan. She feels that her departure should not be so predetermined. And the image seems to back her up. It is unheroic, non-injunctive. It says that a home is not necessarily a departure terminal. It is a waiting area, a place in which to consider, to people-watch, to experience time passing. We can imagine that the two adults in the Ozu image are the two kids in the Tarkovsky image, twenty years later, having done a tour d’horizon and then returned home.

© FLC/DAGP, Paris

In the twentieth century the Swiss architect Le Corbusier started to think about what a home within a home would look like. In his 1959 French priory La Tourette, he wondered what the simplest living space would be for friars meeting for collective experiences – eating, worshipping, teaching, etc. – during the day, within the broader building, but who would then want to retire to private space to study and sleep. After seeing Greek and Italian monasteries and the cabins on ocean liners, he came up with these minimalist, cellular rooms, each of which looked onto a view.

When we want to escape human interaction, he thought, we need a pure space made of simple materials and satisfying proportions. The physical space was small but the looking space was not. Perspective takes your eye to the balcony and beyond. The image is similar to Vincent Van Gogh’s famous painting of his simple bedroom: the bed on the right, a chair and desk to the left, a green floor, a window at the far end, towards the vanishing point.

When we look at our homes and the homes of others we see machines for living. Our sense of the objects in the world grows.

DESIGN AND THE THINGS AROUND US

On the table in La Tourette we can see an Anglepoise lamp, one of the few things in the room that is not at a right angle. Its name alone – Anglepoise – tells us that it cares about geometry and balance. Le Corbusier will have chosen it for its good design.

Design is everywhere. In his book Principles of Gestalt Psychology (1935), German psychologist Kurt Koffka wrote that a handle ‘wants to be grasped’ and that a post box invites you to post a letter. ‘Things tell us what to do with them,’ he argued, and used the word Aufforderungscharakter – literally ‘prompt character’ – to describe how they prompt us to understand how they should be deployed. To ask if something is well designed is to ask if it is a solution, if it functions well in its surroundings, if it makes us think Of course, if it uses materials well, if its form is clear or imaginative, if it makes the thing desirable.

Looking is central to design. A child begins by grasping the things that are closest to it – its own feet and hands. The earliest people shaped tools, weapons and cooking utensils by considering what they had to do, but also what they looked like. We will get to architectural and fashion design later in this book, but for now let’s consider seven objects from the worlds of domesticity, fashion, work, science and sport that early and then later lookers made, and how they were shaped by looking. Each is a design classic. To make it easier to see their forms, none of them have colour.

The first is an Iranian bowl from 3000 BCE, when Egypt was first unified, and when the potter’s wheel was introduced in China.

Its nimble base supports a wide receptacle which might have held herbs, grapes, honey, figs or cucumbers, all of which were eaten at the time. A wider base would have made it sturdier, but the potter will have seen elegance in the contrast in the base and rim circumferences, an opening out, a flowering. Only the inside is decorated. The dark lines are hard edged and bold. They visually echo basket weaving, which was popular in this area of Iran – near both Afghanistan and the Gulf. The painter confidently gives the bowl four rims, and a set of circles which emphasise the volume, the belly. There is nothing figurative here, there are no animals or plants, but there is pleasure in shape, in swooping the eye into the bowl, then around its edge. It was defined twice: once by its maker, then by its decorator. This is a functional object and an optical one.

As is this Celtic St Ninian’s brooch. It is from the early Middle Ages, around CE 800, when Zen Buddhism was dominant in Asia, while Christianity was in central and southern Europe. Vikings were attacking Scotland, where the brooch was found. Made of Pictish silver, it was used to fasten a cape, the centre of the needle being under the material.

In the Iranian bowl none of the bold stripes intersect, but here the silversmith has lines in the top pattern weave under themselves, then dart backwards and repeat the process to meet their own tails and create trefoils. Pictish design delights in moving our eyes in this way. And it loves horseshoe shapes, and playing with circles too. Visually we want to complete the brooch’s main circle, but medallion discs on each arm bring our eyes to a halt with the right amount of visual weight, and five concentric circles in each. The pin boldly bisects all this soft metal curving. The brooch would work just as well with a much shorter pin, but the latter’s length – twice the diameter of the horseshoe – is a confident geometric slash. Wear it at your left shoulder, and the pin points to your heart. Pictish art was often body art, which is why it is so popular in tattoo parlours.

The brooch would have been found only in fancy homes, but this Australian carrying tray would never be. It was made by Aboriginals, in the time before the first European migrants arrived in 1788, from the bark or outer edge of a tree trunk. Women carried fruit, fish or their child in it, holding it under their arms or on their heads.

Its open-ended, concave shape means that it was probably a digging implement too, and also used for separating heavier from lighter granular materials. It is sculpted but also heat-bent. To stop it from cracking and to make it waterproof, it will have been oiled, probably with emu fat.

Our sense of the tool’s beauty comes in part from the fact that it visually echoes nature – the curve of the tree – and also from the sensuality and patina of the oiling. More than that, the designer-artisan has found a shape which underlines, or is inherent within, the three jobs it does: carrying, digging and winnowing. As we look at it, we imagine it doing each, and it starts to seem like a distillation of rural women’s work, a mathematical equation.

In the dark homes of early peoples, it was of course hard to see. In the late 1200s in Italy, monks illuminating manuscripts began to attach to their noses lenses on wire, wooden or shell frames, to enhance their vision, to bring detail into focus. Reading glasses were born and lives were transformed.

In this pair of glasses, from the twentieth century, the upper edge is darker than the lower, and more pointed at each end. The design echoes eyebrows, creating an architrave. In some societies, ideal faces are heart shaped or triangular, with the apex downwards. These glasses’ exaggeration of the brow width plays to that ideal. Earlier models pinched the nose (‘pince-nez’), but these rest on it and, via extended sides, the ears too, thereby applying minimal pressure to the wearer’s skin. The whole front section has not a single straight line, nor do our faces. There is an almost Pictish flow to the design. The jagged lines of the Iranian bowl would work better on a warrior helmet than on these glasses.

The most famous design movement of the twentieth century, the Bauhaus, produced this teapot in 1924.

Human beings by then had produced thousands of pot designs, but not one quite like this. Its main hemispherical chamber has similar proportions to the Iranian bowl – that narrow base/wide brim ideal. But it sits on a cross, and the spout does something like the pin on the brooch: it daggers the curves. The lid is a circle within a circle, but set back to the rear of the pot, to counterbalance the spout-dagger. Beneath the lid is a leaf infusion chamber. The black ebony handle is a half-moon rudder, which makes a coracle of the pot. A century earlier, its surfaces might have been etched and decorated, with metal figures or even a landscape on its lid, but here the lid is an ultra-simple mirror, and we get to see the basic rivets which attach the handle to the body. The designer wants us to look at the pure geometric forms which underlie the object, and also how it is made.

Clearly there was revisionist visual and material thinking at the Bauhaus. The tea infuser’s designer, Marianne Brandt, was a central figure there. The school emphasised the interaction of the arts and, appropriately, she was a painter, sculptor and photographer as well as designer. She and her colleagues were inspired by the medieval craft guild system which emphasised the integrity of materials and practices, as well as the role the craftsperson plays in the city. The Bauhaus embraced the industrial age and manufacturing techniques, but felt that that age’s use of workers as cogs in a machine had resulted in a loss of soul, that designers were not understanding their object, its function and materials, holistically. They had to problem-solve. Design was research. Brandt’s teapots were research. She made several of them as a student in 1924. One recently sold for $361,000.

It is hard to think of two less related objects in human history than a teapot and a space satellite, but look at Sputnik 1, the first manufactured object to orbit the Earth.

It is like two of Brandt’s teapots welded together. Launched by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957, it orbited the Earth every 96 minutes – 1,440 times, before it fell to Earth. The spindles are two sets of antennae. It contained three batteries, a fan for heat regulation and a radio transmitter, and was filled with dry nitrogen.

All this was achieved on a small scale by its design leader Mikhail Stepanovich Khomyakov. He made Sputnik 1 no bigger than a beach ball, and had its surface covered with 1mm aluminium-magnesium-titanium. Function was primary, of course – the satellite had to be a heat-resistant, self-cooling radio station – and yet Khomyakov, like Brandt, used one of nature’s most basic forms, the sphere, as his model. He had an orb circle an orb. It is possible to see the Pictish horseshoe and pin in the Sputnik, and, if we look at the shapes it reflects, the pattern on the Iranian bowl.

Reprinted courtesy of Össur

Coming into the twenty-first century, our last design object is this running blade.

Its shape shows that design sometimes requires a counter-intuitive thought detour. When an athlete loses his or her leg, the obvious thing would be to replace it with something that looks like a leg – vertical with some kind of ankle joint and a telescoping, compressing, shock-absorbing system. The aim, you would think, would be to make the prosthetic resemble a real leg.

But research by the Icelandic company Össur showed that it needed to have horizontal stress capability. Running is, after all, forward, so an unexpected line – a parabola which flattens at the top – became the shape. Material is again key: carbon fibre makes it light, flexible and strong. Though it extends to below the knee, the blade’s shape looks like a foot and ankle, the toes pointing left, the heel raised. Nike designed the lower part of the prosthetic specifically for world-record-holding runner Sarah Reinertsen.

What would the makers of the Iranian bowl, or the Australian tray, have thought of the running blade? By looking at Reinertsen using it, they would have seen, and probably marvelled at, its function. A problem in the world had been solved. It had been solved in conjunction with an awareness of visual pleasure or geometry. It seems absurd to suggest that the Iranian, the Australian, the German, the Russian, the Icelander and the American had much in common, but designers look into the future. They see an object that is not yet there, but that will satisfy when it is. They look beneath the fuselage.

This chapter has been about things, and us as things. It has given our story a set, a set design. We have seen how looking describes self, how homes shape behaviour and how we see how things are used. Looking has been material in these pages, but in the next chapter it is back to immaterial things. We start with desire.