Читать книгу The Lion of Venice - Mark Frutkin - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Conception

ОглавлениеVenice, 1254.

Niccolo, my father, was a practical man, a merchant. He used to say there is no such thing as magic. He used to say, “Do not talk about such things, people won't believe you.” But I have seen it, I have experienced magic. I know it exists.

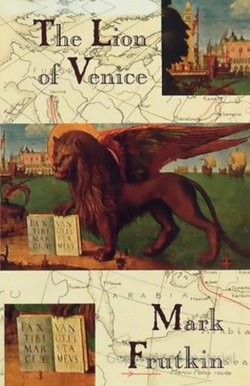

The Lion of Venice, in a pose of extravagant stillness, sniffs the air from atop his column of violet Troas granite. A bizarre, freakish animal, he is half-lion, half-mythical beast. His mouth is frozen open under a cat's nose, and his ears are almost human, though it is nothing like a lion's head. The face, white eyes of faceted chalcedony, emits a kind of demonic intelligence. And wings: unreal, towering wings. He is a rude demiurge, congeries of metals fused around a hollow core, a bound fury, a monster, a beast! His moist nostrils tremble and flare open. The winged statue readies himself to pounce.

Uncanny, impossible scents seem to quicken him into life–crushed almonds, flashes of honeysuckle, lemon, gardenia, clove, as well as the fresh, clean odor of damp earth and starched cotton, stitched by an intriguing ribbon of seaweed.

The doors of the Church of San Marco ease open on a flood of morning light. Adriana stands on the threshold looking out into the blinding square. In that moment, she notices a lustrous current of air curling in from the sea. The square is silent, no one moves. Everything everywhere is still. For a fraction of an instant, all over the city, statues awake to their reflections in the canals. They gaze at themselves, for a moment, in the motionless waters.

And then it passes. The square is stitched, cross-hatched with lines of families leaving Mass, and the statues fall back again into their strong, silent dreams.

Adriana follows her parents out the towering doors of San Marco, floating from the cool shadows into the hard sunshine illuminating the piazza. The wind flips and curls blue and gold pennants at the square's edge. The sea breeze flows over the water, holding off, for a while, the rising heat of a Venetian morning.

The impossible magic of the Mass, of transubstantiation, still worries Adriana. How is it bread and wine can be transformed into His body and blood? How is it that certain things in the world can change into other things? Shading her soft dark eyes, she steps further into the light and looks up.

Adriana is strangely excited, for she thinks she has seen the wings of the statue quiver. She turns and hurries to catch up to her parents, who are working their way to the middle of the square where they greet the Polos, parents of her betrothed.

The fresh morning weather of Ascension Thursday passed and Venice was becalmed in the hottest month of May anyone could remember. Heat drained from every pore of every stone in the city. The sun was barely visible through the haze draped over the lagoons. And yet the sun seemed everywhere at once: bouncing off the viscous water of the canals, flowing out of every crack and crevice in dank alleys, igniting the sweaty gold florins falling on a barrel in Adriana's father's waterfront warehouse. Grackles on roof peaks stood silenced, their beaks spread wide, mouths open. Caught fish hit the air and went slack with the heat, their eyes clouding into white. The night held no relief. The stored heat of day radiated from the stone walls of palaces and churches. Half-dead, unable to sleep, men crowded the squares through the night, dragging themselves along claustrophobic alleys and cortes like sluggish ghosts. The canals offered no respite. The water was the temperature of a tepid bath and smelled like the pus of swamps.

After two desperate nights of twisting and turning in bed, Adriana, on the third, falls into a deep and dreamless sleep.

The Lion, from his perch in the piazza, sees into her balcony, left wide open to admit any chance breeze, and gazes upon her white nightdress, the ringlets of black hair on her forehead soaked by her sweat. He waits and watches.

Rooted to his column on the Molo, the small square near San Marco overlooking the lagoon, his thoughts are echoed by pulses of heat-lightning on the horizon to the east, shudderings of distant thunder from the dead-still sea. In the enormous darkness, a tongue of lightning illuminates the nearby Doge's palace roof and the cobbles of the piazza. It lights up the route through alleys, along canals, across squares, illuminates a house not far from Piazza San Marco, its second-story balcony, a woman entwined in sheets of seaweed- and anise-laden fog.

The Lion stands and stares, stunned by the depth of Adriana's fierce beauty, the dusky glow of her skin, the black shine of her hair, the curves of her limbs. He watches her breathe, gazes into the depths of her. Again, for an instant, all is still: the canals, the sea, even the stars stilled in their traces.

Of course, they blamed Niccolo, the Polo boy, once Adriana had begun to show. They didn't know when or how it had happened, but guessed that the boy must have climbed in an open window when Adriana's father was out, dragging himself through the sweltering alleys during the hot spell after Ascension Thursday. Adriana denied every accusation as, of course, she would. The Polo boy, too, insisted on his innocence.

The families consulted a priest. As he waved his right hand in the air while slipping the proffered coins into the pocket of his cassock with the other, he explained, “It happens. No one knows why; the influence of the planets likely, or some evil done long ago. The Lord Himself knows, in such a world as this. Call me again when the child is born and I will determine its state at that time. Buon giorno and God be praised.”

The heads of both families, being merchants with practical natures, decided that a hastened marriage was the most efficacious cure for the affliction at hand and so Niccolo and Adriana, not unwillingly, for they harboured a deep affection for each other, were hurried to the altar several years earlier than planned. In due time, the child was born and was inspected by the priest. “A slight feline cast to the eyes perhaps, and something odd about the ears–a touch shriveled–but otherwise normal.”

The boy was given the name of Marco, an appellation befitting a long enduring Venetian family, for Mark the Apostle was the city's patron saint and his remains had long before been translated into the Church of San Marco. And indeed, the piazza in front of the church was adorned with St. Mark's symbol, a lion.

The years passed like a single morning, afternoon and evening, the tides breathing in and out of Venice, waves breaking and dissolving on the Lido where sometimes I walked along the beach holding my mother's hand. I was still young and ran off with my friend, Giorgio, to catch up to the parade cutting through the sunlit heart of Venice.

Marco pointed his stick, looked at Giorgio, and shrugged as the two boys watched a man running down the street shouting into the morning air, “Lorenzo Tiepolo is chosen! Lorenzo Tiepolo the new Doge!” As people came to their windows and doors, an excited murmur filled the street.

“Lorenzo Tiepolo! It is impossible!”

“I knew it would be him. Did I not tell you?”

“Are you sure?”

“Did you not hear? Lorenzo Tiepolo.”

“Lorenzo Tiepolo?”

“Si. Lorenzo Tiepolo.”

By late morning, the entire population was surging down the crowded alleys to Piazza San Marco where the new Doge, the supreme ruler of the Republic of Venice, would be celebrated. All were in a festive mood, talking and shouting and gesturing: a crowd of tailors arm in arm singing; men drinking wine; children chasing each other. Marco and Giorgio walked with their mothers, Adriana and Antonia, and Marco's Aunt Graziela who lived with the Polos. The boys would burst into short runs through the crowd only to return and then scurry off again. The women talked excitedly about preparations for the festival that always followed the election of a new Doge.

A fine, early summer breeze whipped pennants at the square's edge as Marco and Giorgio looked over the shoulders of a group of young hooligans throwing dice under the arcades. One of the gamers turned and growled, chasing the boys away. The square was brimming with peasants from the countryside as well as wealthy families with their entourage of servants and slaves. Patrician women fanned themselves as they watched from loggias high above the piazza.

The procession began, and Marco and Giorgio, slim as water weeds and slippery as eels, wormed their way to the front of the crowd.

A flourish of long silver horns sounded as the doors of the Church of San Marco swung wide and out marched, in a fog of incense, sixteen standard-bearers carrying double-pointed banners bearing the image of the winged lion. The wind coming off the lagoon whipped the flags on the square and a spontaneous cheer went through the crowd in the piazza to be joined by those from hundreds of boats crowding the lagoon. Marco and Giorgio held their ears. The lions seemed alive, leaping and flying in unison high above the voices, claiming for Venice not only the land and sea, but the sky itself.

Heralds, musicians and young pages were followed by a phalanx of squires in puffed sleeves and round hats. Canons in long robes, a boy with a crucifix and finally the Patriarch of Venice, the city's highest clergyman, ushered ceremoniously from the doors of the Church. These were pursued by three young boys, ballotini, bearing the Doge's pillow, his chair and his hat. And, finally the Doge himself appeared, the majestic Serenissima, wearing a white Phrygian cap, and an official mantle draped over his shoulders. He was an ordinary man, an old man, and his nose was too long. But Marco soon forgot his surprise when the men in the crowd doffed their round hats and bowed as the Doge passed before them. The long line of the parade snaked about the piazza as the people cheered and whooped, “Viva San Marco! Viva San Marco!”

With a shout, the parade of guilds started across the piazza to present themselves to the Doge, now taking his seat in front of the palace: dyers, sailmakers, tanners, clothing makers (dressed in gold), barber-surgeons (in circlets of pearls), the pattenori who worked in horn or ivory, apothecaries and spicers, charcoal makers, furriers (in robes of ermine and squirrel), pepperers, perfumers, glovers and glassmakers.

As the guild of masons passed Giorgio saw his father and shouted, “Papa! Papa!” so that his father came over to the boy, lifted him up on his shoulders and continued along with the parade.

For the next week, Marco could hear the racket of the festival far into the nights and, in the mornings, when he ran out into the square to meet Giorgio, the singing and music and dancing was starting up again. The celebrants ate mountains of food, pipes and lutes echoed from every quarter, wine ran in the gutters and spilled into the canals.

Yesterday I sat by the waters of the lagoon, my feet dangling over the side and I heard behind me, half a league away, the failing breath of my mother in her sick bed. Now I eat so my chewing drowns out the rasp of her breath. I spoon more fish, more rice into my mouth because the sound of her breath makes me want to weep, to run away, to escape.

I hear also the cut of the ships at sea, the spring caravan, returning from Byzantium.

Something is happening to me. I think my mother is dying and as she does so, my hearing reaches further and further into the distance. A sudden vast silence opens up and my mother's breath, a rattle of stones, echoes into it, and I hear voices whispering from distant rooms, crows complaining on islands over the lagoons, winds gathering across the sea.

My mother always said I had ears like fungi. She would nibble on them whispering, “Ears like crushed jewels, found under the earth or brought up from the bottom of the sea.”

But now sounds, surrounded by an empty silence, fall into them as a cataract pours from cliffs into the waves.

Last night I thought I heard my father's voice (how would I remember?) from some lost place across the world. He was still alive, still alive. I heard him.

“I heard him, Momma. I heard his voice. He's coming back to us, Momma.”

I felt her weak hand lift mine to her cheek and she smiled at me and nodded.

My mother is dying. And my father is worlds away, trying to get back to us– and I hear it all so clearly.

Marco went to his mother's room but his aunt turned him away at the door. As he left he heard music drifting in a window at the end of the hall, from a distant church or priory, the ever diminishing strains of a choir's failing diminuendo, rallentando, smorzando.…

The days go by in a dark dream. Then weeks. Then months. Spring washes in and passes. The summer burns on. I am forgetting.

Since long before I was born, Gesualdo was the oldest, most revered servant in our household. As a child, I would see him shuffling through the halls, his hair and face the colour of ashes, his fingers frightening and thin as the bones of finches. But his voice was a delight, a melodious flow pouring out of him as he hummed ancient songs, his voice a kind of mill-wheel to keep him shuffling along.

If the truth be told, old Gesualdo had done little in his later years to justify his title as servant– fetching a few jugs of water at dawn, emptying a few pails at dusk. The rest of his day was given over to rest and tireless flirting with the young servant girls who flitted about the enormous kitchen where he sat on a wooden stool in a corner near the ovens.

From his stool Gesualdo called to young Marco, in a voice still clear, his throat like the glass reed of the glassblower. Ever since Marco had been old enough to understand, Gesualdo had told him stories.

Gesualdo caressed Marco's cheek. “Soon you will be a man, Marco. How many years have you now? Twelve?”

“I have but ten. Ten I turned, two days ago.”

Gesualdo waved away a middle-aged woman servant hovering behind the boy. “I want you to have this.” He handed a small wooden box with a sliding lid to Marco. “Take it.”

The boy held the box in the palm of his left hand and stared at it.

“Si, si. Open it.”

He did so to reveal a palmful of rich soil, slightly damp, the colour of Marco's dark eyes.

“Smell it. Take some between your fingers and sniff it.”

Marco did as instructed, dipping his thumb and index finger into the box, taking up a pinch of earth and bringing it to his nostrils. A sweet, dusty, distant green perfume with a suggestion of resin blew through him.

“Where did it come from, this soil?”

“I will tell you. When I was a young man, it fell upon me to climb to the top of the column holding the great winged Lion in the piazza, there to remove the soil and weeds that had accumulated over the years under the Lion's belly and about its paws. With each step my fear rose as I ascended the rickety ladder. My heart resounded in my ears like a drum– I was sure I would tumble to my death. At the foot of the ladder my master was passing the day with one of the Doge's councillors. If I had come down from the ladder without completing my task, my master would have been sorely embarrassed. Dio mio, he would certainly have thrashed me, or worse. I forced myself up, a step at a time, growing dizzier with each moment. My master shouted up to me to move along, asking why I climbed so slowly and calling me a laggard. I was bit by his anger and forced my legs to lift one after the other. But, in truth, I also feared that huge shadow of the beast over my head, blotting out the sun. Sweat dampened my palms, low groans escaped my throat. I slapped my forehead– and continued up. Finally, by God's grace, I reached the end of the ladder, my eyes level with the weeds at the top of the column. The beast loomed above me like a dangerous cloud. I took the small shovel from my belt and removed a layer of weeds and soil, dropping them to the piazzetta below, taking care to miss my master and his acquaintance. I breathed in the smell of earth and was calmed by it, my heart eased by the simple odour. As I slid my spade under another patch of black loam, I thought– suolo di cielo, the earth of heaven– it is a contradiction, no? It struck me that the soil had flown bit by bit on the wind and collected on that high place since before my father's father's time. It seemed to me that the soil belonged to the Lion himself, was a part of him, the earth under his feet. I looked out to the nearby lagoons and the shining sea– water everywhere surrounded us– while in my hand I held a bit of soil. I placed it in my pocket and later saved it in this box.” Gesualdo motioned to the box in Marco's hand. “Si, put it away now. And keep it with you. You might need to make use of its magic.”

I didn't know what he looked like, my father, as he had left on a long journey to the East when I was very young. But then he appeared, like a ghost by the well in the corte, and I remembered. It was like looking in an ancient mirror.

Marco walks with Aunt Graziela to the well in the courtyard. They each carry a pair of wooden buckets with rope handles. Aunt Graziela is slow-moving, with a double-chin and a quick smile. Marco watches her lower the bucket into the black of the well. He hears the distant splash and gazes down into the depths.

From behind he hears a whisper and straightens up. Across the corte the dazzling light of mid-afternoon surrounds a pair of gaunt, shadowy figures standing under an arched alleyway. The two men stare at him. Graziela too turns to look at the strangers. No one moves, no one speaks. The men walk forward, ghosts coming out of the past and into the light.

One of the strangers is running towards them. “Graziela!” he shouts, his arms out. “Maffeo!” she screams, as they embrace and she covers his face with kisses. Marco stands back and watches as does the other man. Finally the man takes a step forward and Graziela embraces him too. So great is her emotion, she is unable to speak. She wipes her eyes with the hem of her skirt.

“Where is Adriana?”

Marco looks up sharply. That voice. I know that voice. He stops looking at the man and turns to Graziela who has brought her hand to her mouth.

“You…you don't know?”

“What is it?”

Marco knows now, suddenly realizes with a shiver who this man is.

“A little over a year ago,” Graziela stares at the ground, “a sickness, we don't know what it was. The priest said he had never seen anyone die so quickly.”

Niccolo drops to his knees. Marco can hear the cry rising in his father's throat long before it shatters the silent square.

My father won't tell me about the magic of those lands to the East. But I can feel it oozing out the pores of his skin, can hear it echo in his head. He would rather stick to bolts of cloth and weighing pearls. But I can hear into his dreams. I can listen with the patience of stones.

Marco watches his father test a bolt of wool from a load recently arrived from Bruges. Niccolo rubs his long hands across it as if he has a secret intelligence lodged in the tips of his fingers. He is judging the wool for its lanolin content, deciding on its quality, determining its value. Niccolo is tall and thin with an aquiline face and a pronounced widow's peak. His long straight nose and slightly sad drooping eyes are lowered, looking down now at the wool in his hands.

Despite the years they have spent apart, Marco feels there is no one he knows better. He has absolute trust in this stranger, a man returned from those distant places whose names alone thrill Marco to the depths of his heart.

“Marco,” his father asks without looking up. “Why do you spend so much time staring out to sea?”

“I am listening, father.”

“Listening?”

“Yes– to the chimes of Cathay.”

Niccolo shakes his head. “Never mind. Feel this.” He holds out the bolt of wool and Marco rubs it between his fingers. “Now smell it.” Marco takes in a deep draught from the wool as he has seen his father do in this warehouse many times before. “Now this one.” His father holds out another bolt of cloth. “You see the difference? You understand? This one has more lanolin in it,” he says pointing to the first bolt. “Don't forget. You won't forget, will you?”

I stand, staring at the sea, listening. I hear so clearly now, I am hearing beyond the present, and into the past as well. I face east and hear a voice calling to me– and from behind I hear whispering from my shadow, as if my shadow itself has been given voice.

The voice from behind strikes terror in my heart, but the voice from the East shatters softly into a tinkling of glass, and draws further away, tempting me to follow, calling to me like the sea waves washing down the strand and hissing with foam. And beyond it all I am deaf with a vast silence that never leaves me– as if I can only hear with such clarity because beneath the sounds rests a profound silence.

I hear us preparing to head East again, hear the sound of the wind, the whip of the sail, the waters flowing. If I am to travel well I must learn patience. I must learn how to listen. I must learn about death.

I knew little about death until that night at the shipyards. Since then it has never left me, not for a moment. It is my unshakable shadow, my ticking angel. Its journey an exact replica and echo of my own.

Uncle Maffeo was on his way to check out a small coastal ship he owned with Marco's father. The ship, which usually plied the Adriatic between Venice and Brindisi carrying casks of olive oil one way and loads of timber and glass the other, was undergoing winter repairs. At the last moment, Marco had asked if he could come along.

Broad-shouldered, reserved, Maffeo always appeared to be brooding. Those who didn't know him read the look in his wide face as anger, but Marco knew that as soon as someone spoke to Maffeo his face would light up in a friendly smile.

A weightless snow was falling in late afternoon on the line of empty caravelles shifting at anchor in the yards of the Arsenal. As they stepped from his uncle's gondola, poled by Tadeo, a bearded rangy servant renowned for his silence, Marco could see winter's darkness climbing out of the lagoon and settling down on them from the thick grey sky. Walking past the deserted docks, Marco and his uncle heard the sound of workmen busy inside the sheds: echoes of hammering, shouts, metal clanging on metal. They reached the fourth shed on the left and entered.

Inside the warehouse, the Polo ship stood on logs used to roll it up the ramp from the water, rippling cold and black. An acrid smoke filled the cavernous building, coming from a cauldron of pitch about twelve feet across. Inside the cauldron, the pitch bubbled, writhing and pulsing as if alive. A spidery catwalk rimmed the interior of the building, high above in the drifting dark.

Labourers dipped long-handled pots into the viscous pitch and disappeared down into the ship's hold. Others fed the fire with splits of wood. Still others leaned forward, hammering planks.

“Come with me,” Uncle Maffeo says above the din.

Marco follows him up the ladder leading to the catwalk. As they move along, stopping now and then to survey the scene below, they suddenly hear angry shouts and curses from two men further along the parapet. Marco and his uncle come to a rigid halt. The men have not noticed them. Through the gloom, Marco notices a flash of metal. A moment later, one of the men is falling, the handle of a knife sticking from the side of his neck. He lands heavily in the cauldron of pitch.

Marco stares at the scene below. A labourer runs for a rope, another for a plank, but…too late. The worker sinks backwards into the seething cauldron, sending out gentle black waves as he goes down.

Uncle Maffeo hurries along the catwalk in an attempt to catch the murderer but he has vanished into the night like smoke disappearing into fog. Maffeo finds Marco and talks to the workers about the identity of the men.

A rough old greybeard steps forward. “I recognized the murderer.”

“Yes?” Maffeo nods.

“One of the Doge's assassins. Roberto, our friend, must have been punished for some crime against the Republic. We don't know what it was. He never spoke of it.” The other labourers nod their heads in agreement.

“The Doge's assassin? Then we can do nothing. Before the pitch cools, fish him out and take him to his family. Clean him up first.”

Maffeo takes his young nephew home. Tadeo the gondolier merely shakes his head. On their return trip, Marco fears being alone with his thoughts, but dares not break his uncle's grim silence.

Several days later, Marco woke in the middle of the night scorched with fever, his throat enflamed with catarrh. All that day he struggled in a world half-dream, half-waking nightmare, his sweat caustic to the touch.

Marco's aunt treated him with odouriferous poultices and soothing words. His father watched from the doorway to the boy's room, his forehead etched with concern. A servant was sent to fetch the doctor.

The arrival of Doctor Alberi demanded attentions similar to those surrounding the entrance of a highly placed priest or bishop. After the doctor had discussed the situation with Marco's father and aunt, he took a chair by the boy's bedside. The doctor, who had studied at the famous school of medicine at Salerno (and who let this salient point slip into his conversation with Signor Polo), was a prodigious man who exhibited extreme confidence and skill. Dressed in his fine velvet robes, he would expound upon his suggested diagnosis and its proper cure. Doubt and ambiguity neither entered his mind, nor his speech.

“It is apparent the fever has been caused because he has committed a serious sin. The influence of Mars, often a culprit at this time of year is likely also to blame. What planet rules the boy's birth?”

Niccolo answered, “His planet is Mercury.”

With a sandglass drawn from his bag, the doctor took the boy's pulse and nodded. He swished about a glass beaker of urine collected earlier and stared at it importantly. Marco's aunt held her breath as she watched the glass held loosely in the large hairy hand. If a doctor dropped the urine glass, the patient would die. “Have a servant bring me a sample of the boy's stool as soon as one is available. I would like to inspect it. What has he been eating of late?”

The aunt glanced at Marco's father who nodded for her to reply. “The usual. Eel with rice yesterday eve. And rice again at the noonday meal, with a few greens.”

“Hmmm. You must understand that ague is the heat from the cauldron of the stomach rising up and enflaming the liver and heart. If one eats the wrong foods, under the influence of the wrong stars, and if one has a guilty conscience, the liver will boil, thus overheating the blood. You understand, I am sure. It is most important that the humours be kept in balance.

“Listen closely now. If the fever changes from a hectic one, which it is now, to a tertian or quartan one, occurring every three or four days, you will send your servant to inform me. Tomorrow there is a new moon, whose phase might improve things, depending on the severity of the sin he has committed. In any case, if he will eat tomorrow, feed him nothing but the milk of pulverized almonds. The day after that, if there is no improvement, give him barley water mixed with honey, figs and root of licorice. I will leave some herbs you can give him as well. If after a week there is no improvement, I will bleed him to release the evil vapors and lessen the heat. We will bleed from the side opposite the scorched liver. If a week later, there is still no improvement, he will have to be trepanned– you understand? A small hole will be cut in his skull to release the pressure of the heat mounting in his brain. For the bloodletting and trepanning I will require the assistance of the barber.”

Aunt Graziela brought her hand to her mouth, her eyes wide. A grim look passed over Niccolo's face.

The doctor took Marco's hand in his. “Commend yourself to the will of God, my son, and I am sure your recovery will follow.”

“One more thing,” the doctor added as they were leaving the room. He looked seriously into Niccolo's thin face. “Tonight, while he sleeps, tie a red thread about his left wrist. In the morning remove it and take it to a distant tree where you will tie the thread about a branch. In this way the boy's fever will be transferred. I have no doubt that this approach is in all cases effective. Do not, and I stress, do not allow the boy to pass near the tree or the fever will leap from it again onto him. Do you understand?”

Signor Polo nodded. He then invited Dottore Alberi to dine with them and the physician quickly agreed.

Although the doctor's appetite was hearty, a severe look never left his face and, several times during the meal, he sent a servant to check on the boy. Meanwhile, the doctor regaled his hosts with tales of patients he had treated and the alarming array of ailments and diseases he had witnessed: lepers near Parma; diseases of the skin, the scalp, the ears; the blood-coughers; the blind; the writhings and wailings of the mad; the spastics; the scrofulous; the paralytic; the crippled. The list of diseases went on and on: St. Anthony's fire, fistula, mal des ardents, smallpox, pest.

“The varieties of Death are most intriguing.” The doctor downed his wine and motioned to the servant for more. “Death itself bothers me not in the least, but the very richness, the fertility of possible means to die, is most extraordinary. Do you not agree, Signor Polo?”

Early in the morning, two days later, Marco's fever drives him to the balcony. In the early light, he sees the distant column of the Lion of Venice latticed in a network of scaffolding, looking like a catafalque to bear and honour the dead. For the first time he realizes his city, this occluded jewel of streets and alleys and canals running with black waters turning in upon themselves, is a kind of prison whose only relief is the sea, the open waters beyond the lagoons. Returning to bed he falls into a measureless sleep.

Later, his rheumy eyes open on a flood of radiant light. He regards a scene of unfathomable and marvelous proportions. At first he does not know what to make of it, but with effort he is able to stitch together patches of shadow and light into a fantastical image.

“If this is dream,” he says, “then all men sleepwalk through their days.”

Straddling his bed is the Lion, its gargantuan head forced by the wall to turn aside, its tail curling high up into a corner of the ceiling like an eel caught in its pot. Straight above him, Marco sees the metal belly hatch of the beast hanging open and a brilliant light radiating from within. Marco heaves himself up and stands, peering inside the Lion to find the light's source. Placing his hand on the lip of the hatch he pulls himself up inside and gazes directly into the light. Its brilliance is painful to behold, but he can see that the Lion's eyes are the light's source. Its blank white eyes look both out on the world and in on the emptiness.

Inside the belly of the Lion, Marco runs his hand along the cold metal plate and feels the quivering of the beast's wings.

He works his way up the narrowing neck of the Lion, squeezing through the tight opening, until his head is entirely inside the Lion's head. As if donning a mask, he places his own face against the other's, aligns his eyes with the eyes of the Lion and gazes out over the city.

What he sees is Venice in its early days, an archipelago of islands, fishing boats, frail huts standing like terns in shallow water, the bountiful sea's skin stretching into the distance. Workers tend salt pans, push rollers back and forth to pack the bases of salt. Others around the dogado, the lagoon area, drive larch piles deep into the swamp, hundreds of thousands of posts to support stone houses, shops, churches, palaces. Men swarm everywhere with mallets and iron bars and instruments of calculation and measurement.

Shipwrights busy themselves with supplies of timber, iron and hemp to construct fleets of ships. Venetian traders set sail for far lands, their ships laden with lumber and salt and fish, as well as human cargo– pagan Angles, Saxons, Slavs and Greeks to be sold to the Saracen armies as slaves and eunuchs.

He spies a handful of Venetian merchant-adventurers stealing into Alexandria to loot the crypt of a cathedral, searching carved sarcophagi for the yellowed bones of the Apostle Mark. At last they find them and carry the sacred relics off to Venice where they are “translated,” with appropriate ceremony and vaulted pride, into the Church of San Marco.

He notices a man he takes to be a member of the physicians’ guild, walking next to a narrow canal in a determined fashion. The man is covered from head to toe in an outlandish costume, like a reveler at a masque. He wears a smooth linen gown, a waxed face-mask, a flat black hat with wide brim, glass spectacles, and a foot-long curved bird-beak over his nose. This last is stuffed with herbs and drugs as antidotes against infection and the stench of the dead. The physician stops at the peak of an arched stone bridge to watch a gondola floating past, stacked six deep with corpses crawling with rats. The boat drifts down the narrow canal on its own. On the Grand Canal and across the lagoon, hundreds of gondolas and other boats, also filled with corpses, drift about aimlessly. A long wail can be heard coming from the deep wells of the city's alleys.

Out of the sea-fog Marco sees a thousand ships of Venice return from the East with entire charnel-fields of sacred relics: the bones, hair, teeth and dried bloodied rags of holy men from the Levant, from Crete, from Cyprus; knucklebones, femurs, skin and tufts of hair to be mounted in gold monstrances, displayed like the war-booty of holy barbarians; the ear of St. Paul, the roasted flesh of St. Lawrence, St. George's arm; a wine jar from the miracle at Cana; the whispering skull of St. Cyprian.

A man with a death's-head sigil marked on his forehead shadows his father down an alley.

He wants to scream out to warn his father but cannot, nor can he remove his gaze from the darkening city.

Marco awakens. Jumping out of bed, he hurries to the balcony to check the pillar. The Lion is there, but the scaffolding is gone. The fever has broken.

I love this city. I love its danger. I love its stench. It is a museum of death and decay. I love its patches of half dried blood. I love it even more now that I know I am leaving– for the purple skies of Byzantium.

After winding through a maze of streets behind the Church of San Marco, Marco and Niccolo enter a great hall ablaze with light from dozens of smoky fish oil lamps, torches and thick tallow candles. In his long velvet coat and floppy velvet hat, Niccolo gazes about with a composure born of familiarity. Marco, standing close to him, regards the scene with excitement and alarm. Hundreds of men down flagons of wine and shout at the tops of their voices, in heated argument or carousing song. A group of German merchants shout, pounding the wooden table with their fists. The room resounds with the speech of Milanese, Greeks (some from Crete), and Serbians (from Zara and Ragusa). The groups of foreigners keep to themselves, knowing they are forbidden to discuss trade outside the great fondacos set aside for that purpose. Venetians of all classes and stripes shout and raise their jugs together. Marco's eye is caught by two dark-skinned Turks, who refrain from drink, conferring in soft conspiratorial whispers, their bulbous, onion-domed turbans touching as they incline their heads toward each other. He couldn't take his eyes off them, marvelling at their strange dress, wondering what they were saying to each other. Even with the noise of the crowded hall, he could easily distinguish their voices, intertwining in dialogue like delicate chimes of glass.

“Marco! Marco!” His father pulls him through the crowd. They stop at a table filled with faces Marco recognizes. His father's friends clap and stamp in unison by way of greeting. Father and son sit down next to each other on the bench, joining easily in the conversation.

Marco looks up as a space is cleared in the middle of the hall for a juggler and two dwarf tumblers, whose limbs seemed permanently entwined. When the dwarves roll about the room, Marco is unable to distinguish whose limbs were whose–it appears to be a single double–headed eight-limbed beast. The performance ends and the entertainers unravel from each other, tumbling into the thick crowd and disappearing. An enormously tall, thin negro walks to the edge of the open space, holding up a cask of wine at arm's length. He begins gulping its stiff red stream. As he drinks and drinks, drooling a thread of wine from the corner of his mouth and down his chin, the crowd claps and chants. Finishing the barrel, he falls to his knees and smashes the cask on the flagstones. The crowd laughs and cheers. Next comes a grotesquely fat man, his stomach hanging down to his knees as he raises his cloak and dances about, revelling in his obesity. The crowd shouts and throws coins.

The night wears on as drinkers fall under the tables and others stumble into the night. A vicious knife-fight between two old men is quickly halted, the combatants disarmed, three rosettes of blood on the flagstones at their feet. Marco falls asleep with his head on the table while Niccolo drinks and talks.

As Niccolo and Marco walk through the maze of alleys, arms across each other's shoulders, toward their own corte of San Giovanni Grisostomo, a voice close behind shocks them: “Stop! Do not turn around. Listen closely, Signor Polo.” Marco, with his head slightly turned, glimpses the flicker of a blade and notes a mask. “I come as a friend but on pain of death you must not see me. I bear an important message, so listen closely. A certain enemy is planning to accuse you of crimes against the Republic. You must leave Venice at once.”

“I have done nothing. Who accuses me?”

“You know that must remain a secret. You have made enemies. If you remain, you might well hang between the columns of the Lion and the Saint. You have a few days, but do not hesitate.” Marco turns and catches a ripple of cape as the messenger slides behind a column and disappears.

The next morning, a youth comes to the door of Ca'Polo and whispers in the ear of Marco's father. Niccolo hurries out and Marco follows, unseen. When they come to Piazza San Marco, they see a small crowd gazing at the latest victim of the Doge's purge hanging upside down on the Molo from a rope strung between the columns of St. Theodore and the Lion. The man's throat is slit, his intestines curl down, and blood is caking on the cobbles in the sun. Niccolo walks briskly from the piazza while Marco lingers, frozen in the shadows, staring.

“Marco, next week the spring caravan of ships heads east. Maffeo and I must leave with it.”

“And I. I too must leave.” Marco could see his father trying to decide.

“No. Not yet.”

“If not now, when? Please, father.”

Niccolo hesitated. “Stand up before me.”

Marco drew himself up before his father and righted his shoulders– no longer a boy, not yet a man.

He looked into his father's eyes. “If not now, when?”

Niccolo smiled. “Yes, if not now, when.”

Marco beamed. “Where will we go, father?”

“Byzantium. There is a large community of Venetians there. We should be safe. Come along now. Many preparations await us.”

I walk across the Piazza San Marco to the Molo by the lagoon, taking care not to walk between the columns of the Lion and St. Theodore. Between them I see cobbles coated with blood. A mangy orange cat sits there licking at it.

In the pre-dawn light I hear terrifying screams from inside the Doge's palace. They are old screams still trying to escape its warren of rooms, mingling with fresh cries from victims snatched from their beds moments before. A bilious taste rises in my throat.

I turn to the lagoon where the water is crossed with bands of yellow and pink. I hear a wind starting thousands of leagues behind me– it is already upon me, pushing from behind. I hear it throwing waves onto the shores of Byzantium where the sky is purple, scarlet, amethyst, where the rain falls in drops of gold, where desiccated saints’ bodies float like clouds in the cupolas of the basilicas, where a million voices chant in wondrous elegiac harmonies, their breath sighing through hanging gardens of glass.