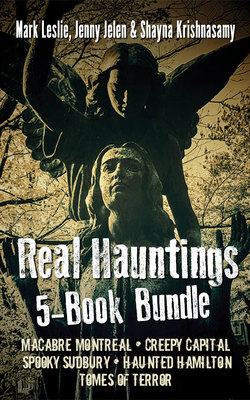

Читать книгу Real Hauntings 5-Book Bundle - Mark Leslie - Страница 44

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Timeline of Tragedies:

Historic Violence, Massacres, and Disasters

ОглавлениеWhen researching a book like this, there are always those interesting stories that lack the detail or support to warrant a full chapter. We occasionally have to abandon those pieces in favour of longer tales with more details to share. However, sometimes there is a theme that runs through some of these shorter pieces, something that provides the thread to sew them together. Combined with a few of the longer items, these can be made into a cohesive chapter that follows a particular theme.

This chapter is a showcase for some such stories and provides a simple timeline of some of the various historical violent incidents, massacres, and disasters, both natural and man-made, that have occurred in Montreal. They show the breadth of tragedies that have befallen the city over the centuries.

* * *

The history of Montreal goes back a long time, long before the arrival of Europeans in the sixteenth century. The land known today as the City of Montreal was inhabited for two thousand years by Haudenosaunee, Wyandot, and Algonquin. Early Algonquin oral history denotes Montreal as “The First Stopping Place” as part of their journey from the Atlantic coast.

When Jacques Cartier arrived in 1535 he renamed the Hochelaga River the St. Lawrence River in honour of the Roman martyr and saint. He also bestowed a new name on the mountain that lies in the heart of Montreal, calling it “Mont Royal” in honour of King Francis I of France. It is believed that the name of Montreal was derived from that. Cartier’s reception by a St. Lawrence Iroquoians nation was a positive one (see “The Missing Village of Hochelaga”). But not all interactions from that point forward were positive. Throughout the city’s early history, there were conflicts and massacres.

Almost seventy years later, Samuel de Champlain built a temporary fort and established a fur-trading post. He would have had no way of knowing that the “temporary” structure would eventually host a population of over six hundred colonists as Fort Ville-Marie (built in 1642), and, eventually, the sprawling metropolis of the City of Montreal.

Champlain would also not have foreseen the bloody battles that would take place on the land, nor some of the tragedies that would befall it. Below is a brief timeline of some of those, with a few additional details:

The Flood of 1642

The steel cross on Mount Royal, which continues to be a significant attraction for visitors to the city, was erected in 1924. But the original cross that it replaced was a wooden one, put there on January 6, 1643, by Paul de Chomeday de Maisonneuve in order to thank God for sparing the local population of the village of Montreal, which had been founded in May 1642.

Shortly after the city’s founding, an unexpected spring-type thaw in December resulted in massive flooding of the land along the St. Lawrence River. The rising flood waters were a real threat to the people of the village. De Maisonneuve prayed to the Virgin Mary to spare the people of Montreal and promised, if his prayers were answered, to erect a cross on a nearby mountain.

After the flood waters retreated, as if in answer to his prayers, he did as he had promised and erected the wooden cross that was replaced more than two hundred and eighty years later.

Bloody Battles and War with the Haudenosaunee

Prior to the arrival of Europeans and the establishment of the fur trade, war among Indigenous nations had a purpose other than the slaughter of one’s enemy. The Haudenosaunee, for example, treated the loss of life and the consolation of a loved one as significant. Due to a belief that the death of a family member had the effect of weakening the spiritual strength of the survivors, it was critical to replace the lost person with a substitute by raiding neighbouring groups in search of captives.

In 1609 Samuel de Champlain recorded that he witnessed a number of battles between the Haudenosaunee and the Algonquin in which very few deaths occurred. This aligned with the understanding that the main purpose of war for the Haudenosaunee was to take prisoners. For the Haudenosaunee, death in battle was avoided at all costs, because of their belief that the souls of those killed in battle were destined to spend the rest of eternity as angry ghosts wandering about in search of vengeance. In fighting against the French, they developed tactics of a quick retreat and setting up stealthy ambush attacks.

During what is known as the Lachine Massacre in 1689, Haudenosaunee warriors launched a surprise attack on the settlement of Lachine, which was located at the lower end of Montreal Island. Here is a description of the attack from the book Ville-Marie, Or, Sketches of Montreal: Past and Present:

During the night of 5th of August 1400 Iroquois traverse the Lake St. Louis, and disembarked silently on the upper part of the island. Before daybreak next morning the invaders had taken their station at Lachine, in platoons around every house within the radius of several leagues. The inmates were buried in sleep — soon to be the dreamless sleep that knows no waking, for many of them. The Iroquois only waited for a signal from their leaders to make the attack. It was given. In a short space the doors and the windows of the dwelling were broken in; the sleepers dragged from their beds; men, women and children, all struggling in the hands of their butchers. Such houses as the savages cannot force their way into, they fire; and as the flames reach the persons of those within, intolerable pain drives them forth to meet death beyond the threshold, from beings who know no pity. The fiendish murderers forced parents to throw their children into the flames. Two hundred persons were burnt alive; others died after prolonged torture. Many were reserved to perish similarly at a future time. The fair island upon the sun shone brightly erewhile, was lighted up by fires of woe; houses, plantations, and crops were reduced to ashes, while the ground reeked with blood up to a short league from Montreal.

The description above appears quite brutal. But, of course, because most of the penned accounts of the attack were written by surviving French settlers, and there appears to be no written accounts from the Haudenosaunee perspective, one must consider them to be biased.

The Great Earthquakes

At approximately 11:00 a.m. on September 16, 1732, a 5.8 magnitude earthquake destroyed major parts of Montreal. Nearly 190 buildings and 300 homes were damaged in both the initial quake and the fires that followed. According to one report (which can’t be confirmed), despite all this destruction only a single person, a young girl, perished.

In an attempt to further investigate this great earthquake, the authors encountered the description of what appears to be a tremendous earthquake that occurred in the same area perhaps fifty years earlier. The following excerpt from Alfred Sandham’s 1870 book Ville-Marie, Or, Sketches of Montreal: Past and Present describes what appears to be a different earthquake that occurred around the year 1663. The detail is taken from an account by the local Jesuits. We found this particular excerpt to be quite the vivid description, without any concern for overstatement or hyperbole.

About half-past five in the evening of 5th February a great noise was heard throughout all Canada, which terrified the inhabitants so much that they ran out of their houses. The roofs of the buildings were shaken with great violence, and the houses appeared as if falling to the ground. There were to be seen animals flying in every direction; children crying and screaming in the streets; men and women seized with affright, stood horror-struck with the dreadful scene before them, unable to move, and ignorant where to fly for refuge from the danger. Some threw themselves upon their knees on the snow, crossing their breasts, and calling on the saints to deliver them from the dangers by which they were surrounded. Others pass the rest of the dreadful night in prayer; for the earthquake ceased not, but continued at short intervals, with a certain undulating impulse, resembling the waves of the ocean; and the same sensations, or sickness at the stomach, was felt during the shocks, as is experienced in a vessel at sea.

The violence of the earthquake was greatest in the forests, where it appeared as if there was a battle raging between the trees; for not only their branches were destroyed, but even their trunks are said to have been detached from their places, and dashed against each other with great violence and confusion — so much so that the Indians declared that all the trees were drunk. The war also seemed to be carried on between the mountains, some of which were torn from their beds and thrown upon others, leaving immense chasms in the places from whence they had issued, and the very trees with which they were covered sunk down, leaving only their tops above the surface of the earth; others were completely overturned, their branches buried in the ground, and the roots only remaining above ground. During this wreck of nature, the ice, upwards of six feet thick, was rent and thrown up in large pieces, and from the openings, in many parts, there issued thick clouds of smoke, or fountains of dirt and sand, which spouted to a considerable height. The springs were either choked up or impregnated with sulphur; many rivers were totally lost; others were diverted from their course; and their waters entirely corrupted. Some of them became yellow, some red, and the St. Lawrence appeared entirely white, as far down as Tadoussac. This extraordinary phenomenon must astonish those who know the size of the river, and the immense body of water in various parts, which must have required such an abundance of matter to whiten it. They write from Montreal, that during the earthquake, they plainly saw the stakes of the palisades jump up as if they had been dancing; and that of two doors in the same room, one opened and the other shut of their own accord; that the chimneys and tops of the houses bent like branches of trees agitated by the wind; that when they went to walk they felt the earth following them, and rising at every step they took.

From Three Rivers they write, that the first shock was the most violent, and commenced with a noise resembling thunder. The houses were agitated in the same manner as the tops of trees during a tempest, with a noise as if fire was crackling in the garrets. The shock lasted half an hour, or rather better, though its greatest force was properly not more than a quarter of an hour; and we believe there was not a single shock which did not cause the earth to open more or less.

As for the rest, we have remarked, that though the earthquake continued almost without intermission, yet it was not always of an equal violence. Sometimes it was like the pitching of a large vessel which dragged heavily at her anchors; and it was this motion which occasioned many to have a giddiness in their heads. At other times, the motion was hurried and irregular, creating sudden jerks, some of which were exceedingly violent; but the most common was a slight, tremulous motion, which occurred frequently with little noise.

At Tadousac the effect of the earthquake was not less violent than in other places: and such a heavy shower of volcanic ashes fell in that neighbourhood, particularly in the River St. Lawrence, that the waters were as violently agitated as during a tempest. Lower down, towards Point Alouettes, an entire forest of considerable extend, was loosened from the shore, and slid in the St. Lawrence.

There are three circumstances which rendered this earthquake quite remarkable; the first, its duration, it having continued from February to August. It is true the shocks were not always equally violent. The second circumstance relates to the extent of the earthquake. It was universal throughout the whole of New France from Gaspé, at the mouth of the St. Lawrence, to beyond Montreal, also in New England, Acadia, and other places more remote. It must, therefore, have extended more than 600 miles in length, and 800 in breadth. Hence, 180,000 square miles of land were convulsed in the same day, and at the same moment. The third circumstance, which appears the most remarkable of all, regards the extraordinary protection of Divine Providence, which was extended to the inhabitants, for while large chasms were opened in various places, and the whole face of the country was convulsed, yet there was not a single life lost, nor a single person harmed in any way.

We found it interesting that both historic accounts, though they each discuss what appear to be different earth-shattering incidents, include references to significantly far-reaching damage, and yet no (or perhaps only a single) human casualty. Could this seeming miracle have anything to do with the cross erected in 1643?

Cholera and Typhus Epidemics (1832 and 1847)

Most of Lower Canada experienced a large scale Cholera epidemic that began in the summer of 1832 (as also described in the chapter “Cholera Ghosts and Un-Ghosts”). In just a matter of days, the reported death toll was more than two hundred and sixty people, and the final death toll is said to have reached approximately two thousand in Montreal.

But that particular epidemic was perhaps just a warm-up for a disease that struck in the following decade. The typhus epidemic of 1847 was linked with the Great Famine, which was caused by potato blight in Ireland between 1845 and 1849. A large-scale Irish emigration on over-crowded, disease-ridden ships led to the death of more than 20,000 people in Canada, including an estimated 3,500 to 6,000 immigrants, who died of this “ship fever” in Montreal’s fever sheds on Windmill Point. (See more about the fever sheds in the chapter “The Heroic Death of John Easton Mills.”)

The Great Fire of 1852

No sooner had Montreal recovered from the mass typhus deaths than a fire that originated at Brown’s Tavern on St. Lawrence broke out, leaving more than ten thousand people homeless (almost one fifth of the city’s population at the time), and destroying half of the city’s housing. The spark that lit the fire occurred, unfortunately, when the city’s recently constructed water reservoir had been drained and closed for repairs.

The Great Inundation of 1861

The City of Montreal has long been a victim of floods, particularly because of the ice that regularly stops up the St. Lawrence River. But the “Great Inundation of 1861” was a particularly significant one, as can be seen in this excerpt from Alfred Sandham’s 1870 book Ville-Marie, Or, Sketches of Montreal: Past and Present:

The inhabitants of the lower parts of the city were accustomed to floods, but they were not prepared for such an extensive inundation as that which visited them in the spring of this year. About 7 o’clock on Sunday evening, April 14th, the water rose so rapidly that the inhabitants were unable to remove articles of furniture to a place of safety, and the congregations of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Chapel, on Dalhousie-street, and the Ottawa-street Wesleyan Chapel found their places of worship surrounded by four to six feet of water, and no means at hand whereby they might reach their homes. The water rushed so violently down the streets that it was almost impossible to maintain a footing while endeavoring to wade through it. In order to obtain assistance for his congregation, Rev. Mr. Ellegood, of St. Stephen’s Church, waded in the dark through about four feet of water until he reached St. Antoine-street. He then procured the assistance of some policemen, and a boat was obtained by which, at about 1 o’clock A.M., the congregation were taken away from the church, with a few exceptions, who stayed all night. The trains from the west and from Lachine were unable to enter the city, and passengers had to find their way to the city by Sherbrooke-street. The principal loss to the inhabitants was in livestock. About 3 o’clock on Monday the pot ash inspection stores took fire from the heating of a quantity of lime. While endeavoring to quench the flames the firemen were standing or wading waist-deep in water. The efforts of the brigade were unavailing, and the building was entirely consumed.

The extend of the inundation may be conceived from the fact that the river rose about twenty-four feet above its average level. The whole of St. Paul-street and up McGill-street to St. Maurice-street, and from thence to the limits of the city, was entirely submerged, and boats ascended McGill-street as far as St. Paul-street. To add to the sufferings of the people the thermometer sank rapidly, and a violent and bitter snow-storm set in on Tuesday, and continued to rage with great fury all night. Owing to the fact that in most cases the fuel was entirely under water much extreme suffering was caused. Considering the rapidity with which the waters rose, it is strange that no more than three lives were lost. These were drowned by the upsetting of a boat, in which they were endeavoring to reach the city. The flood extended over one-fourth part of the city.

Just a few paragraphs later, the text describes the effect of a hurricane that passed over the city in July of that year, creating havoc, tearing down fences and trees, and completely destroying the roofs of the Grand Trunk Railway sheds at Point St. Charles. As with the earthquakes described earlier, all of this seemingly occurred without casualties. In another eerie echo of the earthquakes, July also saw two additional earth-tremor shocks that only lasted a few seconds, but were severe enough to shake buildings and send people rushing out in a panic to the streets.

The “Red Death” Smallpox Epidemic of 1885

In March 1885 a train arrived from Chicago that introduced a plague of smallpox upon Montreal. The disease was transmitted via conductor George Longley, who arrived with an intense fever and a disturbing mass of welts on his face, upper body, and hands.

By the following month, it became evident that smallpox had taken hold of the Montreal General Hospital. A little more than a year later, the disease had infected as many as nine thousand Montrealers, killing more than three thousand and seriously disfiguring countless others.

The real tragedy is that all of this could have been avoided with a simple vaccination, which had been developed in 1796 and was readily available. A good majority of French Canadians, however, were suspicious of the vaccination due to confusing propaganda from the Catholic Church, which included calling those promoting the vaccination “charlatans” and insisting that vaccination was a ploy to poison their children.

The “Saddest Fire” at Laurier Palace

On Sunday January 9, 1927, a horrific and tragic fire broke out in the Laurier Palace Theatre on Saint Catherine Street. The theatre was filled with eight hundred children attending a comedy show. Seventy eight children died in the fire: sixty-four from asphyxiation, twelve who were trampled to death in the ensuing panic, and two from the actual fire itself. It is believed that a hastily discarded cigarette that fell between the theatre’s wooden floorboards was the cause of this tragic fire.

Following this tragedy, the public demanded that children be forbidden from attending the cinema, citing the obvious dangers. Judge Louis Boyer recommended that nobody under the age of sixteen should be allowed access to the cinema. That law remained in effect until 1961. In 1967 the cinema law was adapted into a motion picture rating system that divided audiences into age groups — an interesting by-product of that early theatre tragedy.

Trans-Canada Airlines Flight 831

In what was, at the time, the deadliest airline crash in Canadian history (and currently stands as the third-deadliest behind Swissair Flight 111 and Arrow Air Flight 1285), a Douglas DC-8 crashed about four minutes and twenty miles after take-off, near Ste-Thérèse-de-Blainville. The November 29, 1963, flight, which was bound for Toronto from Montreal, crashed, killing all one hundred and eighteen people on board; one hundred and eleven passengers, and seven crew members.

The only somewhat positive aspect of this story is that traffic congestion on Montreal highways that day led to eight additional passengers failing to arrive at the airport in time to catch that flight.

The actual cause of the crash was difficult to determine, since, at that point, Canadian aircraft were not required to carry voice cockpit recorders. Investigation suggested such possibilities as the jet’s pitch trim system, icing, and failure of the vertical gyro.