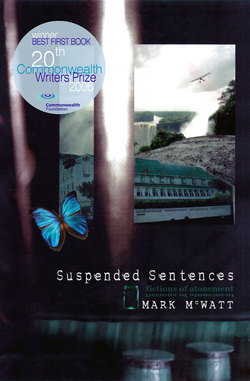

Читать книгу Suspended Sentences - Mark McWatt - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

TWO BOYS NAMED BASIL

Оглавлениеby Hilary Augusta Sutton

Basil Raatgever and Basil Ross were born three days apart in the month of November, 1939. Basil Ross was the elder. From the beginning their lives seem to have been curiously and profoundly interrelated. They were both born to middle-class Guyanese parents of mixed race and their skins were of almost exactly the same hue of brown. They were not related and although their parents knew of each other – as was inevitable in a small society like Georgetown at the time – there was no opportunity for them to meet as young children, because Mr. Ross was a Government dispenser who was posted from time to time to various coastal and interior districts, while the Raatgevers lived in Georgetown, where Mr. Raatgever was some kind of senior clerical functionary in the Transport and Harbours Department.

The two boys met at the age of ten, when Basil Ross began attending the ‘scholarship class’ in the same primary school in Georgetown which Basil Raatgever had attended from the age of six. Basil Ross had been sent to the city to live with his maternal grandparents so that he could have two years of special preparation in order to sit the Government scholarship examinations. The two Basils found themselves seated next to each other in the classroom and from that moment on their lives and fortunes became intertwined. Before the scholarship class neither child showed any particular scholarly aptitude. They both did well enough to get by, but the fourth standard teacher had already warned Mr. Raatgever not to hope for too much of Basil in the scholarship exams; he was restless and easily distracted, though he seemed to have the ability to do fairly well. Basil Ross, on the other hand, possessed great powers of concentration and could occupy himself enthusiastically and obsessively with a number of demanding hobbies, but for him school work was a chore unworthy of his attention, to be done with haste and little care, so that he could return to his more interesting pursuits.

From the time they were placed together in the same class, however, all this changed. Whether this was due to their awakening to the pleasures and possibilities of scholarship – or simply the instinct to compete, to see which Basil was better – in a strange symbiosis they seemed to draw energy and inspiration from each other. At the end of the first term in scholarship class, Basil Ross was first in class, beating Basil Raatgever into second by a mere four marks. At the end of the second term, the positions were the same but the margin was only two marks, and after the third term – at the end of the first year – Basil Raatgever was first in class, beating Basil Ross by a single mark. And so they continued. The change in both boys was great and the marks they achieved were so astonishing that their teacher, Mr. Francis Greaves, remarked to the Headmistress that they seemed like two halves of a single personality – feeding off each other and challenging each other to achieve more and more.

They both easily won Government scholarships to the high school of their parents’ choice, and although the ranking was never publicly announced, rumour had it that Basil Raatgever had scored the highest mark ever achieved in the scholarship examinations and this was two marks higher than Basil Ross’s mark. The scholarships they won, in fact, nearly put paid to their remarkable joint development and achievement, for Basil Ross was a Roman Catholic and opted to attend St. Stanislaus college, whereas Basil Raatgever’s family, though nominally Anglican, did not practice any religion, and wanted Basil to attend Queen’s College, as his father had done. This proved to be a major crisis for the two boys who, at this time, were the best of friends and almost literally inseparable. The two families met and discussed the problem with the boys’ teacher, Mr. Greaves. He reminded everyone that the boys’ remarkable development as scholars began only when they were placed together at adjoining desks, and continued as a result of their strong friendship and preoccupation with each other. He offered the opinion that to send them to separate schools might cause them to revert to the underachievement that had characterized their earlier classroom efforts. In the end it was reasoned that, although Queen’s College was considered to have the edge academically, the difference was small and the boys seemed to need each other more than they needed top quality teaching. So, since religion was of no consequence to the Raatgevers, but of great importance to the Ross family, the boys would go to St. Stanislaus college.

In the first two years at high school, the boys continued taking turns at placing first and second in class; but their strange competitiveness and hunger for achievement began to manifest itself in other spheres, notably on the sports field. Despite their inseparability and the similarity of their accomplishments, the boys were not physically similar. Basil Raatgever was tall for his age and very thin, while Basil Ross had a somewhat shorter, more muscular build. This difference became more evident as the boys grew older, so that when they took to sports they had to settle for achieving equal prowess, but in different spheres. In cricket, for example, Basil Raatgever was a tall and elegant opening batsman, while Basil Ross used his more muscular physique to good effect as a fast bowler and a useful slugger and scrambler for runs in the lower order. In athletics, there was no one in their age-group who could beat Basil Ross in the sprint events and no one who could jump higher than Basil Raatgever. In this way the boys’ symbiotic relationship, their friendship and their remarkable dominance in all the areas in which they chose to compete, continued for the first few years at St. Stanislaus college.

Their schoolmates always spoke of them in the same breath - ‘Ratty-and-Ross’ – as though they were a single person, and boasted to outsiders about their achievements.

It was in the third form that the trouble between the two Basils began. It started, as always, with little things, such as the fact that Raatgever was the first to manifest the onset of puberty. After a brief period of dramatic squeaks and tonal shifts in his voice, especially when chosen to read in class, Basil Raatgever soon acquired a remarkably deep and rich baritone, which seemed all the more incongruous coming from such a slender body. Basil Ross’s voice took longer to change, and in any case did not ‘break’ dramatically like that of his namesake, but deepened slightly over time, so that by the end of that school year it was different, but still high and somewhat squeaky, compared to Raatgever’s. The other boys began to call them ‘Ratty-and-Mouse’.

Then religion played a part in dividing the two Basils. They both did equally well in religious studies and Raatgever, although not a Catholic, attended weekly Benediction and Mass on special occasions with the other boys. But in the third form, Basil Ross was trained as an altar-boy, and, on one or two mornings a week he got up early and rode down to the Cathedral to serve at 7:00 o’clock mass. On those days he went straight on to college afterwards and did not cycle to school with Raatgever as they had done since the first day of first form.

Basil Raatgever pretended to take it in his stride – he knew he was not a Catholic and could not serve Mass, and he discovered that he did not really want to, but at the same time he was resentful that Ross had found a sphere of activity from which he was excluded. Basil Raatgever sulked, and in small and subtle ways he began to be mean to Basil Ross in revenge. On one of the days when he knew that Ross would pass by for him, unfasten the front gate, cycle right under the house and whistle for him, Raatgever ‘forgot’ to chain the dog early in the morning as he always did. The result was that Skip attacked Ross, forcing him to throw down his bike and school books and clamber onto one of the gateposts, putting a small tear in his school pants. Raatgever came down and berated the dog and apologized, but Ross had heard, above the noise of the falling bike and barking dog, muffled laughter coming from the gallery above.

There were other such pranks and, as with everything they did, Basil Ross tried to outdo his friend in this area as well. By the end of that year, when promotion exams were in the offing, each boy ostentatiously cultivated his own circle of friends and the two factions waged continuous verbal warfare.

Then one day Raatgever said: ‘Ross now that we’re no longer friends, I hope I won’t find your name under mine when the exam results are put up – try and come fifth and give me a little breathing space.’

Ross had replied: ‘Ha, you wish! You know I’ll be coming first in class and I’m certain you’ll be swinging on my shirt tails with a close second as usual – but believe me, nothing would please me more than to put a dozen places between us – even if I have to throw away marks to do it.’

Immediately he had said this, both boys were determined to show that their friendship and equality were at an end. The profoundly shocking result was that Basil Ross and Basil Raatgever were ranked a joint 10th in class in the promotion examinations! Even when they were deliberately determined to do badly, each did so to exactly the same extent – in fact they got identical overall marks – and of course, none of their teachers were fooled as they had lost marks with silly, obvious ‘mistakes’. They were both sent in to see the headmaster and letters were sent to their parents along with their reports.

This incident had the effect of making both boys more irritated with each other and, at the same time, more certain that there was some uncanny chemistry going on between them that prevented them from breaking free of each other. They began to feel stifled, trapped in their relationship.

Then there was Alison Cossou. She was a bright, vivacious convent girl who boarded with relatives in the house next door to the Raatgever’s, because her parents lived in Berbice. Basil Raatgever had known her for years and had found her quite pleasant and easy to talk to, but never had any amorous feelings towards her. Basil Ross too had known her casually, as his friend’s next-door neighbour, but when Alison began attending seven o’clock mass at the cathedral and Ross, serving mass, saw her in a different context, he developed a serious crush on her. He would make sure that he touched her chin with the communion plate; this made her eyelids flicker and she would smile and Basil Ross would thrill to a sudden tightness about his heart. Then they took to chatting on the north stairs after mass. When he began stopping outside her gate and chatting with her in full view of the other Basil, the latter felt that he was being outmanoeuvred on his own doorstep and became incensed. So Basil Raatgever launched a campaign to woo and win Alison Cossou from Basil Ross and this new rivalry intensified the bitterness between them, as well as the hopeless sense that their lives would always be intertwined

This situation continued throughout fourth and fifth forms and the boys’ mutual hostility and constant sniping at each other began to irk the teachers as well as their classmates. They were still considered inseparable and still spoken of in the same breath, but now their fellows adjusted their joint nickname, so that ‘Ratty- and-Ross’ became, derisively, ‘Batty-and-Rass’. Even so, they continued to draw energy and competitive zeal from each other, so that St. Stanislaus won all the interschool sports events in those years as the two friends/enemies swept all before them.

A month before the O-level exams began, one of the Jesuit masters at the college – one whom all the students respected – had several sessions with them of what, at a later period, would be called ‘counselling’. He sat them down, spoke to them as adults and reasoned with them. He listened carefully to all the recriminations and made them see that their main problem was a sense of entrapment – their fear that they did not seem to have the freedom to be separate and authentic persons, but must always in some way, feed on each other in order to survive and to achieve.

The priest told them it was indeed a serious situation but their bitterness towards each other was a natural reaction as they grew towards the self-assertion of adulthood. He told them that the problem was that they did not know how to deal with their dilemma and with each other, but if they promised him to try, he would help them devise strategies to either extricate themselves from, or survive, the suffocating relationship in which they had been for so long.

O-levels were thus written under a truce and in the sixth form, with the help of the Jesuit father, their relationship steadily improved. Alison Cossou and two other girls from the convent joined them in the sixth form since the subjects that they wanted to do were not available at their school. The girls had a calming effect on the class, especially on the two Basils, who outdid each other in being courteous and pleasant. In the sixth form too, the Basils discovered parties and dancing and it didn’t take long for everyone to observe with wonder that there was no equality of achievement between the boys in that sphere. Basil Raatgever was a natural dancer – he was self-confident and stylish on the floor and could improvise wonderfully in order to flatter the abilities of all the girls.

The girls were enchanted by him – especially Alison Cossou, who declared one day: ‘The man that will marry me must be able to dance up a storm, because I love to dance.’

Basil Ross heard this with dismay but he admitted defeat to himself and considered that Raatgever had won her – for now. It was not that Basil Ross couldn’t dance – he made all the correct movements and had a fair sense of rhythm, but he did not attract attention as a dancer the way his friend did, and even he loved to watch the sinuous perfection of his friend Raatgever on the dance floor.

No one will ever know how the relationship might have developed after school, for, just after writing A-levels, there occurred a shocking and mysterious event which is still unexplained and which claimed the life of one of the boys and altered irreparably that of the other.

* * *

The priest who taught Religious Knowledge and Latin to the sixth forms, Father De Montfort – the same priest who had counselled the two Basils earlier – accompanied the entire final-year sixth on a trip to Bartica to unwind after the A-level exams. The year was 1957, the third consecutive year that such a trip was arranged, the previous two having been very successful and much talked about at the college. No one guessed that this year’s trip would be the last. There were eight boys, the three convent girls and Father De Montfort himself and they stayed in the presbytery next to the little St. Anthony parish church in Front Street. The girls shared a room upstairs and the boys slept rough on the floor in the large front room downstairs, stowing away their bedding before Mass each morning so that the place could revert to its regular daytime uses.

On their second night in Bartica it was full moon and the young people from Georgetown went walking along Front Street, past the police station and the stelling, around the curve at the top of the street, ending up at the Bernard’s Croft Hotel overlooking the confluence of the rivers. There they ordered soft drinks and bottles of the still new Banks beer from the bar and chatted loudly, imagining that they were behaving like adults. They fed the jukebox near the bar and it wasn’t long before dancing started. Basil Ross, who had enjoyed the trip so far, began to feel uncomfortable; he knew that soon everyone would be admiring and applauding Basil Raatgever as he glided across the floor with one or other of the girls. He told himself it was silly to be jealous, especially now, when, on this trip, he and Raatgever were on good terms again and everyone was in high spirits , after the long slog of preparing for A-levels. Ross told the others he was feeling hot and would take a walk along the river wall to get some air; if he didn’t see them when he returned, he would make his own way back to the presbytery.

The moonlight was brilliant and quite beautiful on the water. Basil Ross walked slowly along the wall, breathing deeply and remembering places in the interior where he had lived and gone to school as a child, and where he had later spent his school holidays with his parents. He sat on the wall not far from the little Public Works jetty and looked at the river and willed himself to be happy. He thought how good it was to have got through the exams feeling confident of his results and slowly his irritation eased. He was happy to be at that spot, pleased that his troubled relationship with Raatgever was resolved. While Ratty might be in love with dancing and the girls, he, Ross, was in love with the whole world, especially the part of it in front of him, touched magically by the silvery moonlight. He sat on the wall for a long time, deciding to say his night prayers and his rosary right there. Then he got up and headed back to the hotel. The jukebox still played, at lower volume, and there were a few men at the bar, but no sign of any of his classmates, so he made his way back to the presbytery. There people were unfolding bedding and getting ready to sleep, so he did the same. Then he noticed that Raatgever was not there. ‘He and Alison went off walking somewhere with a couple of Bartica fellows we met at the hotel,’ someone told him, and he began to feel uneasy again.

The others had gone to sleep but he was still awake, waiting. Some time around two o’clock Basil Raatgever and Alison Cossou came in. They seemed to Basil Ross so mature and self-confident; he felt a pang as they moved carefully about in the almost-dark room. At the foot of the stairs he heard Raatgever whisper: ‘See you tomorrow.’ Alison tiptoed upstairs, but Ross could not help noticing, despite the dim light, that Raatgever had given her a gentle tap on her bottom as she ascended. Ross felt another pang.

When Raatgever was settled in his sleeping bag next to him, Ross pretended to wake up and asked where they had been. Raatgever told him that there had been a dance somewhere in Fourth Avenue and they were invited by two local fellows. The music was good, and Alison wanted to dance, which they did for a while, but most of the men seemed intent on getting drunk and the women looked fed up and uninteresting, so he and Alison had left, walked back to the hotel, sat on the wall and chatted for over an hour in the moonlight. Raatgever did not ask how Ross how he had spent the evening.

* * *

The next day they left early by boat to visit a small waterfall in the lower Mazaruni, where they would bathe and picnic for the day. The boat pulled into a section of riverbank near a small, forested island where the students noticed the beginning of an overgrown trail. It opened out a bit as they got further into it but, although quite distinct, it had evidently not been cleared for some time. The trail crossed a swift-flowing creek by means of a half-submerged log and they began to hear the sound of the waterfall.

When they emerged into a small clearing, Father De Montfort announced: ‘This is it, Baracara Falls’. There the creek cascaded over a stone ledge about twenty feet above their heads and tumbled, foaming and splashing over a heap of large boulders and into a pool whose edges were covered in cream-coloured foam. The boys thought the waterfall was small, but quite impressive, and the water looked cool and refreshing. While their classmates put down baskets and haversacks and prepared to strip and stand or sit on the boulders and let the falling water cool them down after their brief hike, the two Basils, already in swimming trunks, were climbing the falls, one on either side.

Father De Montfort shook his head and smiled and one of the others remarked: ‘Look at Ratty-and-Ross climbing the fall – trust them to make a contest out of it.’ It was not difficult to climb, despite the volume of descending water, as there were many ledges and handholds among the boulders. It seemed as though Ross reached the top first, but soon both boys were standing on the ledge looking down on the others, the water curving high about their calves. After a while those below saw them turn and walk along the rocky ledge away from the lip and along the creek-bed, disappearing into the trees and bushes behind the waterfall. Ross was in front and Raatgever behind him. That was the last anyone ever saw of Raatgever – even Ross, if you believe his story.

The rest of the party bathed in the cold, falling water or in the little pool at its base; a few of the other boys eventually climbed to the ledge as the two Basils had done, but did not venture far along the creek in pursuit of them. All accepted that Ross and Raatgever were extraordinary people and at times it was best to leave them to pursue their own joint agenda. The group had arrived at Baracara Falls just after 10:00 a.m. At 12:30 they had lunch, making sure to leave some for the two Basils. Just before one o’clock Ross appeared on the lip of the waterfall looking troubled.

‘Did Ratty come back?’ he shouted. When they told him that he had not, Ross seemed more agitated.

‘We thought he was with you. We saw him follow you into the bush,’ Father De Montfort said.

‘I thought he was behind me all the time, but when I turned around he’d disappeared. I’m going back to find him.’

And that, essentially, is the story. Pretty soon everybody was topside the falls looking for Raatgever, except the rather corpulent Tony D’Andrade and two of the girls. Alison Cossou had sprinted up the falls quicker than most of the boys. Ross took them to the spot where he said he had turned around for the first time to say something to Raatgever, only to discover that he had vanished. The others were surprised how far they’d gone along the creek; it was quite difficult going in places – there were swampy patches and places that were quite deep and other spots that seemed particularly gloomy and sinister. They could not understand why the two Basils would want to trudge through all that – it was hardly anyone’s idea of fun. Ross said that he and Raatgever had spoken to each other from time to time and that he’d heard Ratty’s footsteps splashing behind him – although when he turned around it was partly because he had not heard anything from Raatgever for a while.

The whole story sounded improbable and one of the other boys said, ‘The two of you concocted this whole thing to play a trick on us – it’s just the kind of thing you two would do. I’m sure Ratty’s hiding in the bush somewhere, or else he’s back at the falls by now, sharing the joke with fat D’Andrade and the girls.’

This immediately seemed plausible to all, including the priest, and they were ready to abandon the search and return to the waterfall, but it was hard not to believe Ross, who was by now visibly disturbed and swore that it was no trick. For more than an hour they shouted Raatgever’s name and searched up and down the creek for him, making forays into the bush wherever there was an opening in the undergrowth through which he could have walked off into the surrounding forest. There was no response and no signs that Raatgever had been there.

The group assembled back at the falls at 4:30 p.m.. By then the three who had remained at the foot of the falls had grown concerned at all the distant shouting and thrashing around they had heard – and at the passage of time. The boatman then came along the path from the river to discover why the group was not waiting on the riverbank at 4:15 as planned, and there was a moment of pandemonium with everyone speaking and shouting at the same time. All were silenced by a loud and desperate shout of ‘Ratt-a-a-a-y!’ from Alison Cossou, who then burst into tears. At that point a profound gloom settled on the group. Led by the Jesuit Father, they prayed that they would find Raatgever – or that he would find them – and then they prayed for his family and the repose of his soul if anything tragic had happened to him.

When it began to get dark and they prepared to leave, Basil Ross announced that he was not going – he would spend the night there and wait for his friend. ‘He would do the same for me,’ he said firmly, and could not be persuaded to leave and return in the morning with the search party. In the end Father De Montfort decided to stay with him. Next morning the others, along with a large and curious group from Bartica, arrived at first light to find Ross and the priest wet and hungry, and miserable because there was still no sign of the missing boy.

For two days searches were made of the forest around the creek and far beyond; then a party of policemen arrived from town with dogs and they spent two days combing the area, but there was no sign of Raatgever. The speculation was that he had wandered far into the forest, got lost and been eaten by a jaguar or had fallen into a bottomless pit. Some said that if he knew how to survive he could wander around the Mazaruni-Potaro jungle for months.

All this was decades ago, and there has never been a satisfactory explanation of the mystery. There were those who harboured the suspicion that Ross had somehow done away with Raatgever – those who remembered their intense rivalry of a few years before; but no one could provide a plausible account of how he might have accomplished this without leaving some trace of this presumed crime.

But what of Ross himself? What did he think? On that harrowing night spent at the foot of Baracara falls, Ross had told the Father that he felt responsible for Raatgever’s disappearance. It crossed the priest’s mind that Ross might be about to confess to having done some harm to Raatgever, and he blessed himself quietly and asked the boy if he felt he needed to go to confession. Ross replied that he didn’t know; he claimed that he had been quarrelling with Raatgever as they walked single file up the bed of the stream. He’d been jealous and angry that his friend and Alison Cossou seemed to be in love with each other and then he’d been annoyed with himself for having these feelings. At the top of the falls that morning Ross had been irritated anew over the fact that he and Raatgever couldn’t seem to get away from each other, that it had occurred to Raatgever to climb the waterfall at the same time that he’d begun ascending the rocks. Then Raatgever had followed him up the stream. After they had walked some distance he had told Raatgever that he was fed up with him and he claimed that his friend had replied tauntingly, saying: ‘You’ll never be rid of me, I’m your doppelgänger. Wherever you go, I will follow, like Ruth in the bible.’ This had made him more angry and he refused to look back at Raatgever, although the latter eventually began to plead with him.

‘I’m only joking, Ross. Look at me, I’m your best friend, I always was and always will be.’

‘I wish you’d disappear for good,’ Ross had told him.

‘You would suffer most if I did,’ was the reply from behind him. ‘Hasn’t it occurred to you yet that we are nothing without each other? It’s your wonderful Catholic religion, Ross, that makes it impossible for you to accept the truth: we are two halves of a single soul. Please Ross, forgive me whatever it is that I’ve done to wrong you: forgive me and accept me – accept yourself.’

‘I wish to God you’d disappear, just disappear! Vanish!’ Ross had heard himself insist in a terrible, hissing voice.

Then, he told Father De Montfort, there was a long silence before he thought he heard Raatgever say, very quietly: ‘All right.’

After that he didn’t hear any sounds from behind him, and after this silence seemed to have lasted several minutes, he looked back. There was no sign of Raatgever and he’d turned and walked further up the stream, convinced that Raatgever was hiding somewhere to make fun of him. Some time later he’d turned back, looking carefully along both banks of the creek, but refusing to call his friend’s name, thinking that Raatgever meant to teach him a lesson by remaining hidden. He’d then returned to the top of the falls. He told Father De Montfort that he still expected Ratty to show up triumphantly, perhaps early next morning, and that his friend was doing this to punish him – adding after a pause that he (Ross) deserved to be punished for what he had said.

But hours later that night, after it had rained and they had begun to hear the noises of bats and animals in the surrounding forest, Ross said to the priest, as though continuing a current conversation: ‘Unless he really disappeared, Father – unless I made him disappear...’

‘And how could you have done that, child? How does one make a human being disappear?’

‘I don’t know, Father.’ And Ross began to weep.

Father De Montfort tried to comfort Ross and, at the boy’s insistence, gave him absolution for the sin of being angry with his friend and wishing for his disappearance. Father De Montfort tried to convince him that, if he was telling the truth, it was illogical to feel guilty, since it was not possible to make a human being disappear simply by wishing it. The priest also advised him not to repeat the story, since it would feed the superstitions of the ungodly and, in any case, was unlikely to lead to the recovery of his friend.

* * *

In August that year it was announced that Basil Raatgever had achieved the top marks in the A-level examinations and would have been awarded the scholarship to do university studies. Ross was named proxime, having achieved the second best results in the country and in the absence of Raatgever was offered the scholarship. He accepted it, reflecting sorrowfully that he and his achievements still seemed tied to his vanished friend. Ross studied law in England, returning to Guyana after four years. He worked for a while in the Public Prosecutor’s office then, in the mid-1960s, he was appointed a legal officer in the Attorney General’s office, and has remained there to the present.

By all accounts, Basil Ross became a taciturn, solitary individual; he played no games, never competed with anyone and neither married nor pursued the opposite sex. He seemed to live for his job, gaining a reputation as an excellent drafter of complex legislation and legal opinion, though by virtue of his position his name was never formally associated with the work he authored. One can guess that this struck Ross as peculiarly appropriate: Raatgever had disappeared because of him, and he might have felt comforted by the thought that there was no identification of self or personality in the work he did; that he, Basil Ross, had disappeared almost as completely as Basil Raatgever. He refused appointments to other, more prominent positions in government service and while his superiors relied more and more on his knowledge and experience, there were others happy to claim the prominence he eschewed.

Ross, in turn, relied on his secretary, Miss Morgan – an efficient, old-fashioned civil service spinster – to keep the office running smoothly and to shield him from public exposure. The country had long forgotten the mystery of Raatgever’s disappearance, although on one or two occasions, not long after his return from England, Ross had permitted himself to be interviewed about the incident. He had hoped vaguely that the interviewer might have some new angle to explore; he knew that he had nothing useful to add to all that had been said before. He had been disappointed on each occasion, and decided he would not subject himself to any more journalistic probing.

People who knew him said that Basil Ross had changed physically after the incident: that he had become thin and ascetic-looking and, as the years passed, his physique began to resemble that of his vanished friend. He lived a life of careful routine – home to office, office to home. He visited his close relatives occasionally, but said very little and seemed to find casual conversation difficult. He remained devout in the practice of his religion and he was careful, through those oppressive years, to keep himself strictly above politics.

That might have been the end of the story, but then, in the mid-1990s, Basil Ross had a revelation. A number of eco-tourism companies had opened resorts in the Essequibo-Mazaruni area and one of these had rediscovered the Baracara falls, cleared the path and constructed a bridge over the little creek. A bathe in the ‘therapeutic waters’ of the falls was advertised in their brochure as one of the attractions of their tour package. This brochure had caught Basil Ross’s attention. This was in 1996. On the brochure there was a small picture of Baracara falls with a few tourists in swimsuits arranged on the top ledge of the falls and on the boulders. Behind the veil of falling water next to the vertical edge of one of these boulders, Basil Ross thought he saw a face. Rationally, he knew it could not be a real face, but he was struck by the fact that it was the first thing he noticed when he looked at the photograph. He visited the office of the tour company, spoke to the proprietor’s son and then the proprietor himself, found out who had taken the photograph and, with some difficulty and expense, managed to locate the negative and have a large blow-up made. This confirmed his belief that the face behind the veil of water was that of Basil Raatgever – the face of his classmate of 1957: the large forehead, the eyes, the wide mouth, the shadow of a moustache. Raatgever, Ross saw, was smiling.

No one else could see the face, though some agreed that there was a suggestion, in the pattern of water falling over rock, of eyes and a mouth – but only after Ross had pointed these out to them. The fact that no one else saw what he saw did not surprise or discourage him. He saw the face quite clearly and had no trouble recognizing it. He had the enlarged photograph framed and hung on the wall of his bedroom and a smaller version stood on his desk at work. He became convinced that the face of his lost friend had been made visible to him to free him from his years of guilt and sorrow, and he felt truly liberated. Basil Raatgever was there after all – had been there all along, there in the falls. He had reappeared in the place where he had made himself disappear in response to his (Ross’s) angry wish.

At the office they noticed that Mr. Ross was more relaxed and approachable. He smiled with uncharacteristic frequency and seemed more inclined to stop and chat with his fellow workers. Some surmised that he was mellowing with age and perhaps looking forward to his retirement in a few years.

One day, Basil Ross stopped before the desk of his faithful secretary. ‘Miss Morgan, I don’t quite know how to say this, but... Well... The fact is that I find myself in possession of two tickets for something called an “Old Time Dance”. I understand that there will be music that was popular in the fifties and sixties and refreshments of some sort. I was wondering if you...’

‘Oh, yes, OK, Mr. Ross, I’ll take them off you – you know I can’t pass up a good dance. I’ll get one of the friends in my little group to go with me. You’re giving me the tickets, or do I have to pay?’

‘Well... You see, Miss Morgan...’

But Miss Morgan didn’t see... She couldn’t see why Mr. Ross was making such a fuss and seemed so awkward. He had passed on many such tickets to her over the years. She couldn’t help thinking that by now people should have realized that Mr. Ross didn’t go to public events of that kind.

‘Well, the truth is, Miss Morgan,’ Basil Ross continued, ‘I thought I would rather like to go myself – for a change, you know... to remind me of my youth, so to speak... Oh, I don’t know, but I was wondering if you would do me the honour of allowing me to escort you.’

Miss Morgan opened her mouth, but no sound came from it. She was stunned. The honour of allowing me to escort you... The words rang in her head for a long time before she worked out that Mr. Ross was in fact asking her out to a dance, and it took her still longer to recover the power of speech and respond.

* * *

The evening at the dance was a revelation to Miss Morgan. She had never associated Mr. Ross with any social skills or with activities engaged in simply for pleasure. She had thought that she would have to humour him and be embarrassed on his behalf for his awkwardness, but would cheerfully endure this while savouring the novelty of the situation. But Mr. Ross danced like a man possessed. He was lively and fluent in the quicker numbers; he twirled her around and pulled her towards him with the utmost grace and perfect timing, but it was the slow, soulful hits of the sixties he seemed to like best. As the music sobbed rhythmically, Mr. Ross swayed and glided, his hips and shoulders drifting effortlessly with the waves of sound, and his feet hardly seemed to touch the floor. It took all of Miss Morgan’s considerable skills to keep up with him and she noticed, with genuine pleasure, that they had begun to attract quite a lot of attention. Several couples, indeed, had stopped dancing to watch them. Mr. Basil Ross was entirely oblivious – he was floating, he was free. It was as if a long lost dimension of self had reawakened within him and was asserting its presence and its hunger for pleasures long denied. One or two of the older folk at the dance thought they remembered seeing someone dance like that before – a youngster, long, long ago.