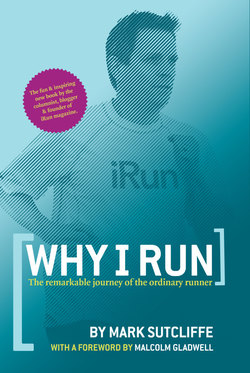

Читать книгу Why I Run: The Remarkable Journey of the Ordinary Runner - Mark MDiv Sutcliffe - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword by Malcolm Gladwell

ОглавлениеI started running when I was twelve because I wanted to run races. At that age, it seemed to me to be the point. The summer before I turned thirteen I remember running up and down a farmer’s track, behind our house, in competition with my brother and my father. We would stagger each person’s starting point, according to some elaborate calculation of individual handicap, and time each interval with a big, old-fashioned stopwatch. My goal, at first, was to beat my brother. Then it was to beat my father. And then, when I entered high school and ran track and cross-country, it was to beat as many people as possible in my age group. Running was a competitive activity, like Monopoly or playing cards, for which the only appropriate goal was victory. Once, after winning a cross-country race in high school, I remember my coach asking me if I liked running, and I was utterly bewildered by the question. I had won, hadn’t I? And I won a lot in those years — local races, provincial races — and that was always my answer. Until, at the grand old age of fifteen, I abruptly stopped winning — and all of a sudden I had to decide how I really felt.

In the pages that follow, Mark Sutcliffe will tell you stories about his own running experiences. Superficially, they are nothing at all like mine. He came to running late. I started early. He runs marathons. I was a miler as a kid, and to this day regard races at lengths greater than ten kilometres to be acts of lunacy. We actually went running once and, predictably, he would have been happier going longer and slower and I would have been happier going shorter and faster. But beneath those surface differences, our stories — like all running stories — are very similar. They are all reflections on running’s great paradox: that this most elemental and primal of human activities is also deeply (and occasionally frustratingly) complex.

How, for example, could I not know whether I liked running? Hockey players don’t wonder whether they like hockey. Of course, they like hockey. Hockey’s great virtue is that it is inherently likeable. Running is not. It is painful and demanding and difficult and frustrating. I did not run for another three years, after my peak at fifteen. Then I began again, in fits and starts, through my twenties and early thirties. But each comeback attempt would founder on the question of why. Remind me why again I’m killing myself in the pouring rain, on some lonely road? Slowly, though, over the course of many miles, I began to work out my answer. I began to realize that something that was painful and demanding and difficult and frustrating could also be beautiful and incredibly satisfying — not in spite of its pain and difficulty but because of it: that those things that come with effort and sacrifice are infinitely more meaningful as a result. What I did not grasp until I was much older was how miraculous running is. You don’t see it at fourteen or fifteen, when physical activity is a given. But now, in my mid-forties, I see it plain as day: that a fully grown adult can go out and run continuously and happily for forty-five minutes is something that — every time I do it — never ceases to astound me.

Am I sounding like one of those tiresome running gurus? Perhaps. And do all runners think of running this way? Maybe not. I suspect that anyone capable of running forty-two kilometres — like Mark — is a bit less conflicted about this particular form of human activity. But I think Mark would agree — and I hope you do as well as you read through this marvellous collection of essays — there is much to be said, and much to be learned, from the deceptively simple act of putting on a pair of training shoes and venturing out onto the roads. Enjoy.