Читать книгу Unseen - Mark Graham - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One

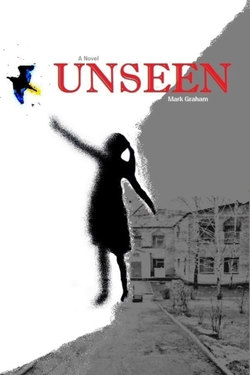

ОглавлениеMariupol, Ukraine

The grounds-keeper caught the director watching him from behind the tall white linen curtains of her office window. He had seen her do this for many years and drive by him on his daily long walk to the bus-stop. He sensed her still observing him as he ambled to the newly installed nine foot high steel front gate at the entrance to the orphanage. He let himself out first, double-wrapped the chains, and relocked it. He stood there for a while looking at what had been his place of work for the past thirty-two years, the old large three-story building of imperfectly placed sandy bricks. Located central to one of the many Soviet era apartment sections of town, the orphanage was surrounded and blocked from all sides. The whole of the property, his kingdom, surrounded by a low endless and expansive wall of the same brick. He had given his best to it, inside and out, to make it appear less like an industrial warehouse. But at each day’s end, the view of it and his efforts disappointed.

His last day. He was still trying to believe it. It would be months before he started receiving his pension and he had made no other plans for the gap. He never even considered his pension, only assumed he would work until his body gave out completely.

Directors came and went over the years, one or two that were good and the rest bad. This latest one being the worst. Many children came to know him well and he always focused on the ones, the few, who could potentially find work when they left. But he was a learner. A man who read and thought. He learned to only invest himself in certain ones eventually and worked to build them up, making them assistants and getting them duty with him in the gardens or strapping on them a tool-belt to follow him around with, cleaning and fixing. Hoping they would grasp something lasting from his ethic and take on some confidence. It had become to him his real job.

He turned from the building. He had eleven blocks to walk to the bus stop. His longevity was in part due to this exercise blended with the breeze coming from the nearby Sea of Azov. At the corner of the fourth block he would normally stop into the store, buy a paper and meet his friends. His friends used to include the customers but that had changed over the years.

He passed the storefront by this evening.

As he walked, he thought of the empty flat that awaited him at the other side of town. His wife had died long ago and too young. He was without children; they had wanted children so badly. When no one was around he would still speak to her about all their children that he tended to. About his love and dreams for them. Each year he looked to celebrate a day when he helped one of his children get a job. Or when he found one had gone off to University on a government scholarship. He bought the little store out on those days. There were six such celebrations in his years at the orphanage. The past five years had been hopeless because of the new director. He managed his work around the other bad ones, but this one was different, maniacal and unpredictable. Also she was in total control while pretending to be at odds politically with some workers and administrators. It took him several years before he understood her act, her lies. And another couple of years to keep himself from the bottle when he returned home.

Part of him was relieved that he witnessed what he had on the second floor, while the part of him, concerned with paying his rent now, wished he had not stayed to listen and been found out. The work was so hopeless anyhow. And the director’s future would probably outlast the remainder of his life. But he had seen them and heard them. He had some skills and sober many years so he did imagine he might still find work, even at his age.

The grounds-keeper reached his stop and was surprised to see her alone there sitting under the canopy. He had been so much in his thoughts that he had not noticed her shiny new car parked in front of the bus-stop. He was certain she had not passed him on the walk, he always noticed that. And her new car was the latest talk of her around the orphanage. He approached her cautiously and sat down at the opposite end of the bench without acknowledging her.

“You know I had to fire you,” the director said.

He did not answer.

“Those girls have a roof and some money. That’s more than they would have on the street and you know it. And they don’t pay for anything.”

The grounds-keeper leaned his body slightly more away from her.

“I know you heard us talking. I don’t need to know how much you heard, you understand. That is enough to know.”

“Why are you talking to me?” he asked.

“I want you to know how serious this is. You know the cook – she was here only six weeks.”

He did remember. The woman had simply disappeared one day. But she had made friends in her short time and they tracked her down to her home town in time to attend the funeral. Because she had accidentally drowned three days before. Drowned in a river she had grown up swimming in every summer of her youth.

The bus pulled up to the curb and the man stood with no intention of a response. Something in him, some primal survival message, told him to speak before boarding the bus. “I understand,” he said.

“Good. Very important.”

“Da,” he replied.

The man stepped onto the bus, found his window seat and dropped into it. He knew she was looking at him but he could not look back. The bus moved and after some time he found the interest to look out the window as they passed the city port and then flowed through downtown Mariupol. The bus slowed and he peered down at two policemen talking it up with each other. He recognized the short one from a day in the director’s waiting room. The grounds-keeper had been there replacing a telephone the director had ripped from the wall and thrown against another wall. The short policeman had been there to get paid for turning a blind eye. When he was young, he believed the uniformed men were really something. They were the people’s refuge and ambassadors of the law. He knew now that the Soviet dream was just a prelude to a nightmare. His people were stronger than that and their heritage deeper. He had always imagined his last days to be of respect and honor. But the image was only four hours old and remained with him. He had been on that wing of the second floor a hundred thousand times before. This day was just unfortunate.

Three blocks from his Kiev hotel, he stood in front of the doors. The doors to the shop were obviously locked but Martin Johnson shook them anyhow. His need for caffeine hoped in any possibility. Even that which was seen with his eyes was not necessarily true, not absolutely. Dawn was breaking but the shopkeepers were not yet active. He turned around to see only old men slouching on park benches, chatting, feeding pigeons breakfast, and one set playing chess. Martin remembered Benjamin Franklin’s saying of “early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise”. From the looks of the men, Martin learned that health and wealth had very subjective and circumstantial definitions. He had left a note for his wife, Jenny, early in the morning that he would be venturing out alone and scribbled down the number to his new cell phone. He started to approach the old men but changed his mind. Six months of hard study prior to this trip and he was still not confident in his Russian enough for random conversations.

This first cool morning in-country, an overwhelming pang settled in his gut as he left the storefront to walk the city sidewalks. It was mostly because of his need of coffee but he could not ignore the fact of his new anxiety. The last time he felt something like this was prior to his wedding day. Not a foreboding, instead a kind of concentrated gravity, deep in meaning and personal.

Martin didn’t like radical change or discomfort of any kind. Joining up with the little group on their mission to help an orphanage was something he had committed to for a lack of something better to do. He was diligent in this and in life to always count the cost, to never blindly leap into anything new. With all of his preparation, and being just a day into Ukraine, it did not feel like a honeymoon. He couldn’t even get coffee the instant he wanted it and feared that there might be more inconveniences that lay ahead.

As he walked the endless broken and cracked asphalt sidewalks of Kiev, the mix of grand Stalin period buildings with their tall columns, carved stone window frames and inlaid with first floor cheaply built modern store-fronts enthralled Martin. He worked his mind away from his normal inclinations and passions, thinking of prayer but without praying. This thing prayer only came to him in times of extreme distress or boredom. He crossed a river; the bridge’s entry way was marked by tall stone posts, topped with golden hammer and sickle ornaments. Martin passed over to the island and then meandered down towards the left embankment of the Dnieper River. A whole community of Soviet period apartment high-rises nestled in place on what his map said was an historic artificial island called Rusanivsky. Nothing was open there either. He continued on carefully down cement steps to the canal level and rested on what was left of a green painted wooden park bench at the water’s edge. He would wait the shopkeepers out. Looking out to the new light expanding across the algae infested water, he ran through the questions burdening him, questions he had not been used to asking. Why was he so tense? What lay ahead for him in the next 10 days? No matter, he was happy just to not be working wherever he might be. If nothing else, he planned to make a vacation out of it all.

Martin looked at his watch and thought of the meetings and ledgers he would normally be entertaining at work at that time. For the 15 years since leaving college, he had been an accountant with the small company. A job he also did simply for lack of interest in something else to do. Most of his promotions were generated by attrition and had been fittingly anticlimactic. It was rumoured that he was on a short list for the future position of comptroller. He knew he didn’t “get along” as well as others, so this had surprised him. Then he remembered the time difference. He’d actually be fast asleep if back home. Martin looked to his map and bits of history knowledge drifted to the forward of his thoughts but the power of their certainty fizzled. The “Evil Empire”, the name he’d been taught from his youth, clearly did not fit this place, or the people. They struggled, maybe, under an overtly oppressive government, but were not partakers of that power. Not folks like him anyhow. In fact, so far it seemed much like his Oklahoma but in an alternate universe. A universe without an EPA, building codes, or fast food and large grocery chains every hundred feet. Martin tightly clamped his eyes and pressed his thoughts out into a single desire and plea to have the wretched question of his anxiety answered. He waited as if for a miracle cure to cancer. But nothing. An hour later, nothing, the pressure of an unspoken purpose was still enveloping him.

He trudged himself back the way he had come and slowly passed one lone old man sitting on another bench. The man, in his 80s, leaned forward with his arms folded over his crossed legs. Martin estimated that his wide-lapelled plaid suit coat must have survived for at least forty years. He was compelled to stop before the man and felt strangely at home near him. The man looked at him as someone pleased, a kind of lonely old uncle expectant of company.

“Hello,” Martin said in his uncertain Russian.

“Hello, friend.”

They remained in silence for a time, what seemed like a very long time to Martin. The man never dropped his aged but alert piercing blue eyes from him.

“You are American,” the man said in English.

“You know?” Martin asked.

“Yes. You are bold.”

“Your English is good,” Martin replied. Bold?

“Thank you. You see that ship there? By the crane.”

“Yes,” Martin answered.

“It’s named after an older riverboat. I worked on that one.”

“Providence.” Martin said.

“Very good. You read Russian.”

“Well, I know the alphabet. You know where I can get coffee?” Martin again gestured as he struggled with words, forgetting the stranger knew perfect English.

“A good ship can take you safely somewhere. But sometimes it is the ship that is the destination. You understand?”

“No. I’m sorry. I need to get going. It was nice talking with you.”

“Okay. You have hryvnia?” the man asked.

The man held his shaking hand out. Martin handed him 10 hryvnia and smiled a goodbye. The old man had seemed extraordinary in the way he had opened up so directly. From Martin’s short experience from the airport to there the man seemed un-Ukrainian.

He called Jenny, telling her that he would meet the group at the Alliance Children’s Foundation compound. From his map, he could tell it was doable without a taxi. Martin, determined to find coffee, wanted more time to shake off the pressure he felt from the inside out.

Along the way back he witnessed shops opening for business. People filled the streets and sidewalks finding their way to their jobs. Many other people appeared to wander about without real direction. Probably unemployed. Martin passed a group of teens that likely should have been in school or at work. Books did not exaggerate the amount of street kids in Kiev. The numbers of homeless youth astounded him as he walked, walked in a way to avoid them. He caught the eye of a couple gang members as he went. Each time their eyes and expressions were identical – he offended them by having some place to go, some place to be. He ducked into the first open café and stood in line for his coffee. The Babushka in front of him turned her head back to look at him. Martin then realized that he had naturally made, with an American sense of space, the only gap in the line.

The Alliance Children’s Foundation compound was immense and was centered in one of the most expensive real estate quarters of Kiev. Inflation was in place and the rental property was a relative match to Manhattan. Martin walked through the stately gates of the A.C.F. feeling uneasy. His ideas of second-world ministries were nothing like he had observed. He knew there were people in the field, missionaries who suffered along with those they ministered to. This was not it. This was where they organized and networked all those missionaries. They also networked with hundreds of other non-profits in the country through what they called “partnerships.”

The A.C.F. resembled to Martin a little of the American government in the way that they were the dispenser of major funds, allowing them a far-reaching oversight of likely too many things. His little rag-tag group had gathered outside one of the doors on the third floor. He reached them and heard that he missed the tour of the state-of-the-art television studio. Apparently it was breath-taking.

He couldn’t have been less interested if he had desired to be. Why he came all this way in the first place, Martin wasn’t sure, but it wasn’t to meet-and-greet TV personalities or ogle electronic equipment in a studio. He took a place next to Jenny and they followed the team down the many stairs and out into the parking lot. The chief of the A.C.F., recognizable to Martin from his previous fretful Internet searches, walked out of the building with a couple of his aides following close behind. The man seemed bothered, a bitterness masked by a smile that Martin had seen before from so many salesmen.

The leader of the mission led the group closer to the chief and by the van that was to take them to the train station.

“Hello, everyone. Welcome to Ukraine. Translated, it means Borderland and you guys are headed to our southernmost border region today. I tell you, I envy you your work in Mariupol. Word has gone ahead and the children are very excited. The director is as well. I have known her for many years and I think they will be as much a blessing to you as you are to them. Thank you again for your heart for the Ukrainian children.”

The chief gave more energy to his final smile, waving before disappearing back into the building.

“What’s his name, again?” Martin asked.

“Chip Stiles. He’s really nice,” Jenny replied.

“So just his little speech sucks?”

“Stop it,” she whispered.

“Fine.”

On their way to the train station Martin had made it his goal to try to understand the Ukrainian traffic signs and rules. Was driving and parking on sidewalks okay all the time or just at certain hours? They encountered a traffic light at several intersections where the rule seemed to be that all cars met in the middle and fought their way across.

It was early evening by the time they arrived at the Kiev city train station. Their group was guided into the station, a place as bustling inside as outside. The airport had nothing like the volume of people in this place which showed to Martin that this country relied heavily on the train. Looking around the entryway he saw that the ceiling reached at least 100 feet high, held together with giant and ornate stone columns. Hanging from this incredible height was the largest chandelier he had ever seen with large baroque style fresco paintings bordering the highest rim full around the room. Did they have Soviet symbolism in the same way Masonic temple buildings back home had mystical meanings?

Jenny tugged him along with the rest of the herd to the window where they could exchange their money. These little currency exchange stations seemed to be everywhere. Martin had little interest in the people on his team before today, but now they made themselves pronounced, annoying, and embarrassing. An older couple bickered with the exchange agent and between themselves. Another man still complained about his having missed lunch. And one woman spoke loudly of how she was so humbled by the poverty she had seen on the way to the station.

Martin finally found the words to pray, but the answer was apparently ‘no’ because they were all still talking.

“These people, Jenny.”

“Stop it. It’s fine,” Jenny said.

“Yeah, okay. But come on.”

“You don’t like groups or crowds. You don’t like anyone taking care of you. It makes you crazy.”

“Da,” he said and laughed.

“Oh, the language. You have to have an interpreter. That must be killing you. I’m sorry, it’s not funny.”

“It’s like I’m a baby, you know.”

“You’re my baby.”

The A.C.F. people walked them all to their track where they boarded four to a cabin. Martin had not thought ahead to how this would play out, the men sleeping in one room and women to the other cabins. He had a book though, his salvation. The pretty stewardess appeared at his door to take drink orders. The word for coffee was so close that he did not have to offer help in translation for the other members of his group.

As she turned and walked out of the cabin, Martin watched as all eyes of the cramped cabin followed her out. Two of his cabin mates stood and followed her out of the cabin, pretending some other purpose. One of the men intensely read a wall placard written in Russian, and the other man pretended to be interested in the view out the window, glancing repeatedly back at the stewardess as she walked down the corridor. Martin smiled for the first time in days. Even landing this job must have been competitive and the woman’s looks had likely been her salvation.

When she returned with his coffee, he took it to Jenny’s cabin, interrupting her chat with the other women. She always looked so happy to him, so excited about most everything they did. This adventure might as well have been one of her weekend shopping trips to Tulsa with her girlfriends.

They linked hands, walking a few cabin doors down.

Jenny stopped them and spread the curtains on a window. She squeezed his hand while he stared at her looking out at the passing urban landscape.

“We’re almost out of the city now. What are all those metal boxes? Mini-storage?” she asked.

“No, I don’t think so. Those are assigned car garages for the nearby apartment buildings.”

“Oh. That makes sense. There are a lot of small cars here.”

“Really? Whatever.”

“What?”

“Look at those garages. How can you validate them? They’re ugly welded steel boxes. And the apartments are worse than our ghettos at best.”

“What’s your point, Martin?”

“Nothing. I feel weird here. Everybody zipping along a never-ending junkyard and acting like everything is normal.”

“This is their normal. Get some sleep,” Jenny said.

She smiled and kissed him good-night.

Back in his cabin, Martin climbed into his top bunk. He lay there; face three inches from the ceiling, struggling to breathe for several hours. Though brochures declared some trains were now fitted with air-conditioning, his was not. The train shuddered through several slowing-to-stop experiences. One seemed to take longer to slow than others as outside lights flash-filled his cabin. Sensing the big city he saw on the map earlier and still in his clothes, he crept quietly out of the compartment and out onto the terminal platform.

A monotone Russian female voice echoed through the air reading something informative and boring over the station loud-speakers. The tone reminded him of that hollow flat gong and dull sound of the Greenwich Mean Time statement on short-wave radios. The kind his uncle gave when he was a kid. The one he had fiddled with in lieu of having friends. The station was surprisingly quiet and empty in the darkness of early morning for a city as large as Dnepropetrovsk. He walked along the long line of makeshift kiosks made of old cargo pallets covered with large canvas and plastic tarps. Some kiosk owners slept curled next to their sales-stands, wrapped tightly in blankets and Persian carpets. He imagined how busy they would soon become, full of smiles and desperate sales pitches. All of them running back and forth from train to train to make change.

A large cement slab stage separated train tracks, providing Martin ample room to pace and stroll. All the trains were painted solid blue, each with a long yellow stripe along the sides, matching the colors of the national flag. Most of the boxcars were newer, maybe ten to twenty years old. The older trains interested him more as he imagined early cold war drama around them. Never leaving sight of his train car, Martin counted the cars as he walked. His home was on the other side of the planet while here he was a stranger. He felt the sudden loneliness of that fact.

Jenny had urged—and he had planned to follow her suggestions—to take many pictures and make diary entries, interacting with as many locals as possible to deepen his travel experience. But his poor disposition concerning change and the stress of it was too much. Every time he thought to follow her recommendations, he simply did not have the energy. He was into day two of ten and had no more interest in anything than getting to day ten and ending the trip. To get back to the life he had neglected to reflect upon and appreciate. But at the same time, Martin knew he was wasting something good for himself, something lasting.

The question burned from his chest, “Why do I do what I don’t want to do? Why don’t I do what I want to do?”

The woman’s voice came over the speakers again. This time he associated the sound of it to a scene in Doctor Zhivago, adding another layer to his surreal experience. She mentioned the transit number for his train and he double-checked his ticket. One of the attendants of his train hung from the edge of the steps, waving him over.

It was accommodating to have their assistance in getting back to the right car quickly, but it annoyed him. He certainly didn’t need anyone’s help.