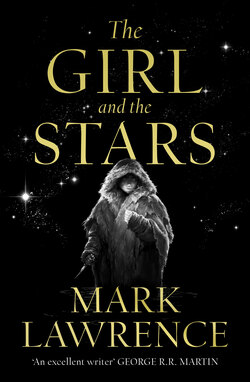

Читать книгу The Girl and the Stars - Mark Lawrence - Страница 7

CHAPTER 1

ОглавлениеIn the ice, east of the Black Rock, there is a hole into which broken children are thrown. Yaz had always known about the hole. Her people called it the Pit of the Missing and she had carried the knowledge of it with her like a midnight eye watching from the back of her mind. It seemed her entire life had been spent circling that pit in the ice and that now it was drawing her in as she had always known it would.

‘Hey!’ Zeen pointed. ‘The mountain!’

Yaz squinted in the direction her younger brother indicated. On the horizon, barely visible, a black spot, stark against all the white. A month had passed since the landscape had offered anything but white and now that she saw the dark peak she couldn’t understand how it had taken Zeen’s eyes to find it for her.

‘I know why it’s black,’ Zeen said.

Everyone knew but Yaz let him tell her; at twelve he thought himself a man, but he still boasted like a child.

‘It’s black because the rocks are hot and the ice melts.’

Zeen lowered his hand. It seemed strange to see his fingers. In the north where the Ictha normally roamed the whole clan went so heaped in hide and skins that they barely looked human. Even in their tents they wore mittens any time fine tasks were not required. It was easy to forget that people even had fingers. But here, as far south as her people ever travelled, the Ictha could almost walk bare-chested.

‘Well remembered.’ Yaz would miss her little brother when they threw her into the pit. He was bright and fierce and her parents’ joy.

‘You’ve spotted it then?’ Quell came alongside them. He had no sled to drag and could move up and down the line checking on the thirty families. He nodded towards the Black Rock. ‘I remember how big it is, but still, it always surprises me when we get close.’

Yaz forced a smile. She would miss Quell too, even though at seventeen he boasted nearly as much as Zeen.

‘Always?’ she asked. Quell had been to the gathering twice. Once more than her.

‘Always.’ Quell nodded, almost concealing his grin. He held her gaze for a moment with pale eyes then moved on up the column. He passed Yaz’s parents and uncle, who between them pulled the boat-sled, pausing to swap a comment with her father. One day soon he would have to ask her parents for permission to share Yaz’s tent. Or so he thought. Yaz worried what Quell might do when the regulator picked her out. She hoped he would prove himself grown enough to embrace this fate and not shame the Ictha before the southern tribes.

‘Tell me about the testing,’ Zeen said.

Yaz sighed and leaned into the sled traces. She had of course told Zeen everything a hundred times over but she had been the same herself before her first visit to the hole.

‘You’ll be fine.’ Zeen’s worries were nothing, it was just the mind turning on itself when there wasn’t anything to do but pull a load mile upon mile, day upon day. The journey had proved difficult, the ice rucking up before them in pressure ridges as if seeking to impede their progress. For the last week the pace had been gruelling as the clan-mother sought to make up lost time. Still, they would arrive a day before the ceremony. ‘Don’t worry about it, Zeen.’

On Yaz’s first trip south she had been sure the regulator would sniff out her wrongness. Somehow she had passed inspection. But that had been four years ago, and what had been starting to break within her back then was now fully broken. ‘You’ll be fine.’

‘But what if I’m not?’ The sight of the Black Rock seemed to have opened the gates to her brother’s fear.

‘The southern tribes are not like the Ictha, Zeen. They have many that are born wrong. We have to be pure. Weakness was bred out of us long ago,’ she lied. ‘When you walk the polar ice you are either pure or dead.’

‘Strangers!’ Quell came hurrying back down the column, excited. ‘We’re getting close!’

Yaz looked to where her parents had turned their heads. Faint in the distance a grey line could be seen, another clan trekking in from the east. And between the two columns, a single sled closing on the Ictha at remarkable speed.

Zeen stopped to stare in amazement. ‘How can—’

‘Dogs,’ Yaz said. ‘You’ll get to see your first dogs!’ Even now, as the distance narrowed, the hounds pulling the sled resolved into dots in a line before it. Soon she could make them out against the snow: heavy beasts, silver-white fur bulking them up still further, their breath steaming before them. In the far north the cold would kill them, but south of the Keller Ridges all the tribes used dogs. The Ictha said that a true man pulls his own sled. The southerners laughed at that and called it something that only a man with no dogs would say. Even so, everyone gave the Ictha respect. Anyone who has known cold understands that only a different breed can dare the polar ice.

‘Get along!’ Behind them the Jex twins shouted. Zeen started forward again just in time to avoid having them drag their boat-sled over him. Yaz kept level with her brother, watching the strangers approach.

Within a few minutes the whole column came to a halt while at the front Mother Mazai greeted the men dismounting their sled. Yaz could smell the dogs on the wind, a musky scent. Their yapping rang in ears unfamiliar with anything but the voices of men, of the ice, and of the wind. The sound had a strangeness to it and a beauty, and she found herself wanting to go closer, wanting to meet with one of these alien creatures, bound just like her to a sled by strips of hide.

‘They’re so different!’ Zeen struggled out of his harness and broke from the line to get a better view. He meant the people not the dogs.

‘I know.’ It had been the first thing to strike Yaz at her previous gathering. It wasn’t so much the difference of the southern tribes from the Ictha, it was that even among themselves they were varied, some with the copper skin of an Ictha, some redder, so dark as to almost defy colour, and some much paler, almost pink. Their hair varied too, from Ictha black to shades of brown. Even their eyes were not all the white on white that Yaz saw at almost every turn but a bewildering range. Many had eyes almost as dark as the mountain behind them where the rock won clear of the ice. ‘Don’t stare!’

Zeen waved her off and edged up the column for a closer look. She understood his fascination. Mazai said that where there are many tasks, many kinds of tools are needed. The Ictha, she said, had a single task. To endure. To survive. And to survive a polar night required a singular strength, one recipe. The clan-mother spoke of metals and of how one might be mixed with others to gain particular qualities. There was, she said, a single alloy fit for the purpose of the north, and that was why all who dwelt there held so much in common.

Yaz edged out to join her brother, ignoring her mother’s hiss. Soon they would cast her down the Pit of the Missing into a darkness from which there was no return. She might as well see as much of what the world had to offer as she could before they took it away from her.

‘That one’s the leader.’ Zeen pointed to a man who stood taller than any Ictha and thin, too thin for the north. In places strands of grey shot through the blackness of his hair.

In the months-long polar night the breath you exhaled through your muffler formed two types of frost, the normal southern one, and a finer ice that would smoke away into nothingness within the tent’s warmth. The Ictha called it the dry ice for it never melted, only smoked away. In places, in the depth of the long night, dry ice would drift above the water ice and, when the sun’s red eye returned, a great cold fog would rise in clouds miles high. The storyteller had it that dry ice formed when part of the air itself froze.

Yaz knew that if the thin grey-haired southerner were to draw breath on a polar night the cold would sear his lungs and he would die.

‘Back in line, you two.’ Quell came up behind them, the gentleness of his voice taking the sting from the reprimand. He steered Zeen back into place with a hand on his shoulder. Yaz wished that Quell would lay his hand upon her shoulder as well. The sight of naked fingers still amazed her. If she were going to die then she should experience a man’s touch too.

She had thought many times about pitching her own tent and inviting Quell in. Of course she had. Too many times and for too long. But in the end two things had always stopped her: sometimes one, sometimes the other, sometimes both. Firstly something in her rebelled at the idea that fear should force her hand before she was properly ready. It was not the Ictha way. And secondly there was the pain that Quell would feel when they took her from him. It would not be fair to use him like that.

Three things. Something else had held her back too. And might have been enough on its own even without the other two. A rebellion against a choice that seemed already to have been decided for her.

But Quell and Yaz had walked the ice together since the days when they could first stand on their two feet, and many of her dreams were filled with thoughts of the bold lines of his face, the strength of his hands, and the mix of kindness and bravery with which he tackled the world. She did not want to leave him. When the regulator cast her down her heart would at last be broken like the rest of her, though at least the pain would not continue long, and in death she would join the spirits of the wind.

Yaz returned to the line and watched Quell go forward. Like Zeen he wanted to listen to the southerners. She found a smile on her lips. The regulator might declare a man grown, but they were still just taller boys.

Perhaps she should have set her tent for him. But in any case she was still counted a child and properly they could not be bound until she had endured the regulator for a second time. Almost every broken child was culled from their clan at their first gathering, but even though it was as rare as melting, sometimes it took a second, and no child was truly counted as grown until their second gathering. So in many ways Quell had been a true member of the clan since he was thirteen whereas Yaz, at sixteen, was still seen as a child and would be until tomorrow when the regulator turned his pale eyes her way.

Her mother offered Yaz a knowing smile then looked away as the wind picked up, laden with stinging ice crystals. There had been sadness in that smile too.

Yaz looked down at her hands. Fear prickled across her. It seemed cruel that just one sleepless night away the hole waited for her, an open mouth that would devour all the days she had thought she owned. A future taken. No tent of her own, no boat to set upon the Great Sea, no lover taken to the furs. Maybe there would have been children. At least now Yaz would not have to harden her heart and watch while they in turn stood beneath the regulator’s gaze.

The clan-mother said it wasn’t cruelty. All the tribes knew that a child born broken would die on the ice. Their bodies lacked what was needed to survive. As they grew, the weakness in them would grow too. Some needed too much food to keep warm and would starve. Some would lose their resilience to the wind’s bite and the cold would eat at them, taking first the tips of fingers, nibbling at the nose and ears, later taking the toes. Flesh would turn white, then black, then fall away. In time the fingers and face would be eaten, dying then rotting. It was an ugly death, and painful. But the worst was that the weakness in that adult would pass into their children, and their children’s children, and the clan itself would rot and die.

There was a wisdom to The Pit. A harsh wisdom, but wisdom even so. The burden that Yaz had carried with her out of the north, which had hung from her shoulders each and every mile, was the same weight that set sorrow along the edges of all her mother’s smiles. Years had not blunted the sharpness of Azad’s death. Yaz should be leaving her parents with two sons to support them, but when the dagger-fish broke the waters her strength had not been sufficient to hold her youngest brother, and in what now seemed one long moment of horror he had gone, leaving her alone in the boat. If the regulator had seen at the first gathering that she was broken, Azad would have known his eighth year, and would have had many more to come.

A muttering ran down the column, one passing the news to the next, with a rumble of discontent echoing in its wake.

‘What? What is it?’

Yaz’s father ignored Zeen and told her instead, while the Jex twins leaned in to hear, ‘The Quinx clan-father says our count is out. The ceremony is today.’

‘Why aren’t they there then?’ Yaz’s hands began to tremble, a sweat prickling her skin despite the freezing wind. In the months of polar night it was difficult to keep track of days, but she had never heard of the count being out. ‘Was their count out too?’

‘A hoola attacked their column. They had to observe the rites for the dead. They’re force marching to get to the ceremony in time.’

The Jexes were already passing the news back. As the sun began to set, the regulator would commence his inspection. He would be finished by full dark. If they missed it Yaz would have four more years, albeit forced to remain as a child. From where she stood four years looked like a lifetime. ‘What will we do?’

‘We’ll march too,’ her father said.

‘But … it’s twenty miles or more, and it’s nearly noon.’

‘The Quinx are going.’ Her father turned away.

‘The Quinx have dog-sleds to carry the young and rest the grown!’ Yaz protested.

‘And we,’ her father said, ‘are the Ictha.’

The endurance of the Ictha was a thing of legend among the tribes. The Ictha husbanded their strength. Nothing could be wasted on the polar ice. Not if you wished to survive. But when called upon to do so they could run all day. Yaz began to flag after the second hour. Quell ran beside her as she started to labour, his brow creased with a pain that had nothing to do with effort. He was trying to shield her from notice, she knew that. Somehow hoping that he could drag her along by sheer power of will. Behind her the Jex twins’ relentless strides devoured the distance. Quell could try to hide her weakness. Others could turn a blind eye, perhaps not even admitting it to themselves. But the regulator would see. There was no hiding from him.

The Ictha could not let the Quinx open too large a lead even if they did have dogs. Old rivalries ran too deep for that. The Quinx didn’t even recognize Ictha gods but held their own, some of them twisted versions of the true gods, others entirely foreign. It was a duty of the regulator and his kin in the travelling priesthood to settle disputes and keep the peace. They witnessed oaths, blessed unions, and ensured the purity of all bloodlines. The priests knew all the names of every god, both true and false, and even had a god of their own, a hidden one whose name was secret. The clan elders told stories in which priests of old had channelled the power of their Hidden God to devastating effect, blasting the flesh from the bones of oath-breakers.

Yaz dug deep. Whatever recipe made the Ictha so suited to their environment had gone astray in her. She lacked what the others had. The cold reached her before it reached her friends. Her strength failed against tasks that others of her age could master. She had begun to notice it about a year before her first gathering. Around the same time that she found the river.

There are, impossibly, rivers that run beneath the ice. Yaz’s father said they were the veins of the Gods in the Sea and that enchantment made them flow. Yaz had seen, though, that if you press on ice with enough force it will start to melt where you press hardest. In any case, Yaz’s river was not one of those that run beneath the ice and are seen only where they sometimes jet forth into the Hot Sea of the north or the three lesser seas of the south. Hers was a river seen only in her mind. A river that somehow ran beneath all things, and through them. When she was ten Yaz had started to glimpse it in her dreams. Slowly she had learned to see past the world even when it filled her waking eyes. And everywhere she looked the river ran, flowing at strange angles to what was real.

Now, as she ran, her heart hammering at her breastbone for release, her lungs full of exhaustion’s sharp edges, she saw the river again. And she touched it. In her mind’s eye her fingers brushed the surface of that bright water and in an instant its terrifying power flooded through her hand. The river sucked at her, reluctant to let her go, but she pulled free before she burst. Heat and energy filled her, flowing up her arm and into her body. This was how she lived. Touching the forbidden magics of the first tribe to beach on Abeth, driving away the cold and the hunger and the weariness. It wouldn’t last and she would not be able to find the river again for days, but for now she felt as if she could run forever with a boat-sled on each shoulder, or dance naked in the polar night.

‘I’m fine.’ She made a smile for Quell and picked up the pace, hardly noticing now that she was even running.

‘I know you are.’ Relief washed over Quell’s face and he fell back to check the line.

Yaz fixed her gaze on the sled before her, making sure not to run too fast. She kept her bare hands in fists, knowing that the tips of her fingers would still be glowing with the power now pulsing through her veins.

Around the gullet that the tribes name the Pit of the Missing the ice is rucked up in concentric circles of ridges like the waves left when a leaping whale has returned to the ocean. Yaz always thought of the ridges as curtains, positioned to hide something shameful.

The ice around the outer slopes was littered with the sleds of many clans. Dogs waited in groups, tethered to metal stakes, and here and there a warrior stood guard.

‘Don’t stare.’ Yaz’s father cuffed his son without anger and pointed the way.

The Ictha would drag their smaller sleds up among the ridges. Yaz’s people had few possessions and the loss of any of them was often fatal, so even though theft was a great rarity among the tribes, the Ictha always kept what little they had close to them.

‘Quell will have pretty words for you at the gathering tonight.’ Yaz’s mother stood beside her. They were of a height now. It felt strange to stand eye to eye. ‘He’s a good boy, but be sure he speaks to your father first.’

Yaz’s cheeks burned, though a moment later sadness washed away any embarrassment. She almost broke then, almost sought the warmth and safety of her mother’s arms and cried out to be saved. But her mother had already turned to go, and there was no saving to be had. The world had no place for weakness.

More than half of the sun’s huge red eye had sunk behind the horizon by the time Yaz started to climb. The energies that had sustained her for hours began to fade, leaving her to labour up the slopes. Suddenly each breath burned in her throat, sweat froze on her skin, every muscle ached, but she endured, and all around her the clan kept pace. Behind her she could hear Zeen struggling too. Unencumbered the boy was the fastest of any of them, his hands were just as swift, falling to any task with blurring speed. Harnessed to a load, however, his stamina was less than the others of his age.

By the time they reached the top of the first ridge Yaz was helping to pull her brother’s sled as well as her own. By the third ridge she was pulling both almost by herself. She worried that her strength would fail and she would arrive at the testing having to be carried by her father. The fact that she lacked the full hardiness of her people was the first sign of being broken. The next common sign was that a child would grow too quickly and eat too much. Perhaps these ones were destined to become giants but giants had no place on the ice. Others lived too fast for the ice; they moved more swiftly than anyone should be able to, but they aged quickly too, and grew hungry quickly, and however fast a person is the cold cannot be outrun. Rarer still, they said, were the ones that developed strange talents. Yaz had never seen such a witch-child but whatever magics they had at their disposal were no match for the night freeze, and be they witch, quickling, or giant they paid a price, losing their ability to endure the white teeth of the wind. Yaz wasn’t particularly tall for her age, neither was she unnaturally swift, but her Ictha endurance had been eroding for years. The river gave her ways to hide these failings. They wouldn’t fool the regulator though. Clan-mother Mazai said that the regulator could see through lies, she said he could even see through skin and flesh to the very bones of a person, and that all weakness was laid bare before him.

The Ictha left their sleds at the base of the final ridge and Rezack, who was strong and keen-eyed, remained to watch over them. Yaz descended into the crater around the hole, exhaustion trembling in her legs. She and Zeen were towards the rear of the column now. Quell had fallen back to watch over them, his brow furrowed with concern, but this was not the time to be seen helping. That would do nothing for Yaz’s chances with the regulator.

The tribes had shaped the crater to their purposes, cutting a series of tiers into the ice. The space encircled by the ridges was maybe four hundred yards across and more than two thousand people crowded the level ground, an unimaginable number to Yaz who had spent almost every day of her life with the same one hundred souls.

At the last moment before they reached the crowd below, Quell pulled Yaz to the side, standing precariously on the slanting ice while others passed nearby with the practiced indifference of people with few chances for privacy.

‘Yaz …’ A nervous excitement, most un-Quell-like, haunted Quell’s face. He released her hand, struggling to make his mouth speak.

‘Afterwards.’ She placed a hand against his chest. ‘Ask me when it’s done.’

‘I love you.’ He bit down as the words escaped him. His eyes searched hers, lips pressed tight against further emotion.

And there it was, out in the open, delicate hope trembling in a cruel wind.

Quell was good, kind, brave, handsome. Her friend. All an Ictha girl could dream of. Yaz thought that maybe the first sign that she was broken wasn’t the weakness but that she had always wanted more. She had seen the life that her mother lived, the same lived by her mother’s mother in turn and on and on back along the path of years. She had seen that this life of trekking the ice between closing sea and opening sea was all that the world had to offer. In all the vastness of the ice, with small variations, this was life. And yet some broken thing inside her cried out for more. Though she stamped upon that reckless, selfish, whining voice, pushed it down, shut it out, its whispers still reached her.

I love you.

She didn’t deserve such love. She didn’t deserve it for many reasons, not least that the broken thing within her called it burden rather than blessing.

I love you. Quell watched her, hungry for an answer, and behind her the last of the Ictha shuffled past.

The Ictha knew themselves each as part of the body, and they knew that the body must be kept alive, not its parts. Sacrifice and duty. Play your part in the survival engine. As long as the flame is kept alight, as long as the boats remain unholed, as long as the Ictha endure, then the needs and pain and dreams of any one piece of that body are of no concern.

‘I …’ Yaz knew that if she somehow walked away from the pit this time then she was more than lucky to have Quell waiting for her; she would be more than lucky to resume her trek along the life that had always stretched before her across the ice.

Her heart hurt, she wanted to vanish, for the wind to carry her away. She did want Quell, but also … she wanted more, a different world, a different life.

‘I … Ask me at the gathering. Ask me when this is done.’ She took her hand from his chest, still worried for the heart beneath it.

She turned and followed the others, hating herself for the look in Quell’s eyes, hating the broken voice that gave her no peace, that left her dissatisfied with the good things, the voice that told her she might look the same but that she was different.

Quell followed at her heels and Yaz walked on, unseeing, understanding a new truth on her last day: Abeth’s ice might stretch for untold miles, but there was, in all that emptiness, no room for an individual.

The ceremony was already in progress as Yaz caught up with her brother. On the lowest tier, with only the dark maw of the hole below them, the children of seven clans belonging to three tribes queued in a great circle. Every few moments the line shuffled forward as each boy or girl presented themselves to the regulator in turn.

The old priest stood cloaked in an inky black hide that belonged to nothing that Yaz had ever seen hauled from the sea. Hoola claws reached across his shoulders and fanned out across his chest, threaded on a cord around his neck. His head was bare and bald, marked like his hands with a confusion of burn scars, symbols perhaps but complex and overlapping.

The Ictha said that Regulator Kazik had overseen the gathering for generations. While the other priests came and went with time’s tide, growing old, retiring to the Black Rock, Kazik it was said remained immune to the years. A constant, like the wind.

Today he was the regulator, merciless in judgement. Tomorrow he would be Priest Kazik and he would bless marriages, and laugh, and mix with the clans, and become drunk on ferment with the rest of the grown.

Yaz and Zeen joined the rear of the queue with a score of other Ictha children. One more came up behind, delayed by his mother’s arms. At the front, around a third of the crater’s circumference from them, another child escaped the regulator’s scrutiny. She scrambled away to join her parents watching from some higher tier.

Yaz shuffled forward with the line. The climb still burned in her legs and her chest felt sore from panting.

‘That was tough!’ Zeen smiled up at her. ‘But we made it.’ He stood close to the edge where the ice sloped sharply away towards the hole.

‘Ssshhh.’ Yaz shook her head. It was best to avoid any thoughts of weakness. They said the regulator could read a child’s mind just by staring into their eyes.

‘Has anyone been thrown in?’ That was Jaysin behind them, just nine, as young as any Ictha were tested. The younger children remained at the north camp with the old mothers. ‘Has anyone gone down yet?’

‘How would we know, stupid?’ Zeen rolled his eyes. ‘We just got here too.’ He moved behind Yaz to stand with Jaysin.

Yaz glanced at the hole and shuddered. Even here in the south the ice lay miles deep. She wondered how far she would fall before she hit something.

‘Are they down there?’ Zeen kept glancing at the pit. The closer they got to the regulator the further Zeen positioned himself from the edge. ‘Are the Missing watching us from down there?’

‘No.’ Yaz shook her head. Most likely all the pit held was a sad pile of frozen corpses, the broken children properly broken at last and removed from the bloodline. Some of the southern tribes spoke of the Ancestor’s Tree and of pruning it, but Yaz didn’t know what a tree was and her father, who had spoken to southerners at gatherings across the years, had never met any who had seen such a thing.

‘But they call it the Pit of the Missing,’ Zeen said.

‘It’s the children who are thrown down there who are missing.’ Little Jaysin spoke up again from behind Yaz. It seemed fear had made the boy brave. He rarely had the courage to speak outside his own tent.

‘It’s a different sort of … Oh, never mind.’ Yaz would let someone else explain it to him after she’d gone. Instead she looked up at the sky, pale and clear above her, laced with strips of very high cloud, their edges tinged with the blood of the setting sun. The Missing had lived on Abeth an age before the tribes of man beached their ships upon its shores, but they were all long gone by the time men navigated the black seas between the stars and came to this world. Many southerners treated them as if they were gods, though the Ictha knew that the only gods were those in the sea and those in the sky, with the ice to keep them from warring upon each other.

‘I’d rather just be left out of the tent,’ Zeen said. ‘If I was broken I’d rather just be left out.’

Yaz shrugged. A quick death beat a slow death, and at least this way you gave honour to your tribe. Also there was the issue of metal. Clan-Mother Mazai said that the priesthood was the only source of metal in a thousand miles, and not just pieces of it as might sometimes be traded between the tribes, but worked metal, fashioned to meet demand, be it knife or chain. The ceremony honoured the god of the Black Rock and that in turn earned the clan favour with the regulator. Dying here would help the clan.

A sudden cry jerked Yaz from her thoughts. The regulator was standing alone, the wind tugging at the tattered strips of his cloak. There was no sign of the child that had failed his inspection, just the faint and diminishing echoes of their screaming that still escaped the hole. A stillness pervaded the watching crowd, and they had already been still.

With a bored gesture the regulator beckoned the next in line.

‘I’m scared.’ Zeen’s hand found hers. He had been scared all along of course, but this was the first time he’d spoken the words.

The world turns whether we will it or not and everything, longed for or feared, comes to us in time. The queue leading to the regulator advanced slowly but it didn’t stop, and at last Yaz’s world narrowed to the point towards which it had spiralled for so long.

‘Yaz of the tribe Ictha and the clan Ictha,’ the regulator said. He never needed to be told name, clan, or tribe. The other tribes had several clans, but in the north they shrank to the same thing.

‘Yes,’ she said. To deny your own name was to cut a small piece from your soul, Mother Mazai said.

The regulator leaned in towards her. He had the familiar white-pale eyes of her own clan and seemed unconcerned by what the southerners called cold. The burns across his face, head, and hands looked as if he had been branded with some kind of writing, but with lines of symbols at differing angles and sizes, overwriting each other into confusion. He bent closer, showing his teeth in something that was not a smile.

‘Yaz of the Ictha.’ He took hold of her hand with hard, pinching fingers.

His scent was unfamiliar, sour and as different from the Ictha as the dogs had been. He was old, stringy, gaunt-faced, and looked displeased with the world in general.

The regulator had not touched Yaz on her first visit. Now he seemed unwilling to release her. The tattered strips of his cloak blew about them both and for a moment Yaz considered what would happen if she grabbed them when the time came that he threw her down. The image of his surprise at being hauled in with her struck through Yaz’s fear and she struggled to suppress the burst of hysterical laughter that was pushing to escape her.

‘You’ve seen it, haven’t you, girl?’ He looked up from his inspection of her hand and met her eyes.

‘N … No.’ Yaz shook her head.

‘You should have asked “what?”. All the ice tribes are terrible at lying but the Ictha are the worst.’ The regulator ran his tongue over the yellowing stumps of teeth worn down by years. Without warning he jerked Yaz’s hand to his face and began to sniff at her fingertips. She tried to pull away, disgusted, then realized that if he were to release her as she tugged she would fall back with only the slick gullet of the pit to receive her.

‘Seen what?’ she asked, too late to be convincing.

‘The path that runs through all things.’ He let her go with a last sniff. ‘The line that joins and divides. Seen it and …’ His gaze fell to the hand she now clasped to her chest. ‘And touched it.’

‘I didn’t …’ He was right though. She didn’t know how to lie.

‘That makes you rare, child. Very rare.’ Something ugly twisted on the regulator’s thin lips: a smile. ‘Too good for the pit.’ He nodded to the other side of him. ‘You stand over there. You’ll come with me to the Black Rock.’ Excitement tinged his voice. He had thrown children to their death without affording them the respect of caring. But now he cared.

So, numb and trembling, with her wrist still pale where the regulator had gripped her, Yaz moved on. She stood on the flat ice of the tier, watching without seeing while the others shuffled forward one place. She had survived. She was grown and equal to any in the clan. But still she stood here, forbidden to return to where her parents waited. To where Quell waited. Her gaze tracked back up the stepped ice, across the sea of faces, towards the heights where the Ictha families stood.

‘No.’ The regulator’s quiet announcement drew Yaz’s attention back to the line. His skinny old hand was clamped over Zeen’s face, fingers spread across the boy’s forehead and cheekbones. ‘Not you.’ And with the slightest shove he sent Zeen stumbling back. For a moment Yaz’s brother stood, caught on the edge of balance, his arms pin-wheeling, and in the next he was gone, sliding down the steep slope of the gullet then pitched into the near-vertical darkness of the ice hole. He fell with a single short cry of despair.

Silence.

Yaz’s face had frozen in shock, her voice gone. The thousands stood without sound. Even the wind stilled its tongue.

It should have been me. It should have been me.

Still no one spoke. And then a single high keening broke the silence. A mother’s cry from somewhere far up near the crater’s rim.

It should have been me.

The Ictha endure. They act only when they must. They guard their strength because the ice does not forgive failure.

It should have been me.

Yaz glanced at the blue sky, and in the next moment she threw herself after her brother.