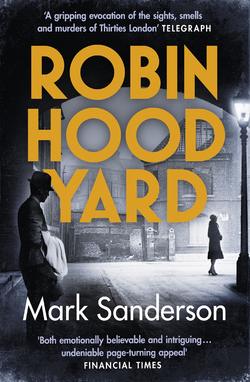

Читать книгу Robin Hood Yard - Mark Sanderson - Страница 13

FIVE

ОглавлениеMonday, 31 October, 8.30 a.m.

Despite reports to the contrary, the world was not coming to an end. Planet Earth had not been invaded by Martians. Johnny grinned at the gullibility of the public. The War of the Worlds was a radio play, not reality. Did no one read H. G. Wells across the Atlantic? All the same, he couldn’t wait to hear the programme.

Orson Welles, the director, claimed the whole thing had been a prank to mark Halloween. If so, why had it been broadcast the day before? And why had it created so much hoo-ha?

There was nothing new about using fake news bulletins for dramatic effect on the radio: Ronald Knox had used them in Broadcasting from the Barricades on the BBC, during which rioters were supposed to have taken over the streets of London. Johnny suspected the American press, like its British counterpart, was suspicious of the relatively new medium, afraid of its ability to report news so much quicker, and was seizing the opportunity to bash the competition. However, with Germany and Japan banging the drums of war, it had been cynical of Welles to capitalize on fears of global invasion.

“The balloon won’t go up for another year or so, if Wells is to be believed,” said PDQ. “In The Shape of Things to Come he predicts that a new world war will begin in January 1940.”

“Let’s hope he’s wrong.”

“Let’s hope you haven’t done anything wrong. Stone wants to see you.”

The red light above the door to the editor’s office went off and the green light came on. Johnny tapped on the polished wood and entered.

“Ah, Steadman. What have you been up to now?” Victor Stone peered at him over the top of his half-moon glasses.

“Sir?”

“I’ve had a call from our new Lord Mayor. Anything to tell me?”

“Wish I had.”

Stone smiled. “Stand at ease. Must be getting old, Steadman – no one’s complained about you recently. Quite the opposite, in fact. Leo said what a personable chap you were. I gather you met on Saturday.”

So Adler and his boss were on first-name terms …

“He wants to know who attacked him. Doesn’t trust the police.”

“Quite. Yet they’ve already ascertained the attackers used pig’s blood. Talk about adding insult to injury.”

“Attackers? Adler said the man was alone.”

“Indeed. But, according to the times established by the bluebottles, a single individual couldn’t have attacked all five banks as well as Adler.”

Where was Stone getting his information from? Why hadn’t anyone told him this? It was supposed to be his story. Johnny knew better than to ask.

“Is Adler clean?”

“As far as I know. Go on …”

Conscious of the black eyes boring into him, Johnny obliged. “Well, pigs aren’t kosher, are they? Jews consider them unclean. The blood could be a reference to some sort of dirty business. Insider dealing is even more common than people suspect.”

“Adler has only got where he is today by being whiter than white. He is extremely conscious of his reputation.”

“He that filches from me my good name …”

Johnny, not for the first time, had opened his mouth without thinking. Iago was a villain and, at this moment, quoting from Othello immediately raised the spectre of Shylock.

“Precisely. Reputation, reputation, reputation! Lose the immortal part of yourself and what remains is bestial. That’s why you must help him. It’s your number one priority.”

“So the two murders are less important?”

Stone stood up and came round the corner of his enormous desk. The fitness fanatic did callisthenics every morning in his office. “Beauty hurts!” was his catchphrase. He had a good body and, as a member of the Open-Air Tourist Society, was not afraid of showing it.

“Anyone else been killed?”

Johnny could smell the carrot juice on Stone’s breath. He stood his ground.

“No.”

“Anyone been arrested?”

“No.”

“Anything new to report at all?”

“Not at this point.”

“Well, get going then. Who’s to know what your snouts have unearthed? If they haven’t heard anything about Adler’s attackers they may have heard something about the dead men.”

He strolled over to the window that – despite the janitor’s best efforts – was still flecked with blackout paint.

“Adler isn’t going to speak to anyone but us. It’ll be an exclusive. One in the eye for the Financial Times. A successful outcome would benefit us all – especially you. Herr Patsel is an excellent news editor, but he can’t stay here, cling on to power, much longer. A reshuffle is on the cards.”

“I’m a newshound, sir, not a house cat. I belong on the streets not behind a desk.”

“Think about it. Now go get me a story.”

Most newspapers used City spies and featured City diaries – published under such pseudonyms as Midas and Autolycus (“a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles”) – to prove it. The City had a tradition of secrecy and worked hard to cultivate its mystique. Attempts to cast light on its activities were viewed askance. Consequently, relations between Fleet Street and Threadneedle Street were often strained.

In the Square Mile it wasn’t only the streets that followed mediaeval courses. The business of buying and selling remained the same. The exchanges didn’t like change. Profit always came at someone’s expense. It was all a game: beggar-my-neighbour or strip-Jack-naked.

Johnny shared Dickens’s opinion of bankers. The crooked financier Mr Merdle – who was full of shit – lived down to his name. Was Adler a mutual friend?

Moneychangers – even before Jesus threw them out of the temple – had never been popular. In a time of hardship though – and when wasn’t it? – Johnny deemed it obscene to be a fat cat while everyone else was tightening their belts. The poor, as Jesus said, were always with us, but that didn’t mean they had to be grist for the City’s satanic mills. Moneymen were routinely demonized in some sections of the press. To counter this, Sir Robert Kindersley, the head of Lazards – aka “The God of the City” – tried to establish a “Bankers’ Bureau” to enhance the image of the Square Mile. However, when the clearing banks failed to cooperate, the talking shop failed.

The City could only do what it always did: put a brave face on it. The banks conducted their business in imposing buildings, the columns – whether Corinthian, Ionic or Doric – hinting at the figures being totted up by hand-operated machines inside. Tap-tap-tap screw! Tap-tap-tap screw! However, it was all a front. The white stone was hung on steel girders like so much sugar-icing. Inside, the banking halls had their own marbled façades. Behind the mahogany veneers, away from the public gaze, there lay a maze of dark and dingy cubbyholes where the real work was done. No matter how much money was donated to charity, bankers couldn’t disguise the fact that, robbing from the poor to give to the rich, they were the opposite of Robin Hood.

Which of his informants should he call first? Johnny reached for the phone but then pushed it away. He would speak to them face to face. It would make it easier to tell if they were lying.

Hughes, no doubt, would be bothering corpses at Bart’s: he wasn’t going anywhere. Culver had switched bucket shops but wouldn’t be free till the evening either. Quicky Quirk, on the other hand, had been released from Pentonville only last week. It was time they caught up.

Lila Mae would not stop screaming. It was astonishing that such a little thing could make so much noise. Lizzie had fed her, changed her, rocked her and sung to her without success before giving up hope and returning the baby to her cot in the boxroom that Matt had decorated. He had been so proud, and so pleased, when she’d told him she was pregnant. Rampant too.

Lila’s brick-red face was scrunched up, her tiny fists clenched, her bootied feet kicking the air. Lizzie, sleep-starved and nipple-sore, stared at her daughter. How quickly a bundle of joy became a ball of fury.

If she cried much longer she would have a convulsion. What was the matter with her? What should she do? She picked Lila up and clutched to her breast. For a second there was silence then, lungs refilled, the caterwauling resumed.

Lizzie walked round the room, shushing her baby, whispering into one of her beautiful, neat ears.

“Hush-a-bye baby, in the tree-top, when the wind blows the cradle will rock …”

The rocking horses on the wallpaper seemed to mock her. Was she going off her rocker?

Who could she call? Not her mother. She’d offered to pay for a nanny, but Lizzie didn’t want a stranger under the roof of their new home. When she’d said she could manage, her mother had said nothing but smiled as if to say she knew better. Maybe she did. Lizzie wasn’t going to admit it now.

She couldn’t stay within these four walls any longer. She’d never felt so alone or so frustrated. She had to get out. Perhaps a ride on a choo-choo train would do the trick.

The incessant rumble of traffic in Holborn Circus came through the ill-fitting window. A draught wafted the thin, striped curtains that shut out prying eyes. The occupant of the top floor room remained oblivious. All the person could hear was a man screaming for his life. Sheer, naked terror. When it came down to it, that’s all there was.

The freshly sharpened, freshly polished knife reflected the killer’s handsome face. The sealed vial stood to attention on the table. Mask, gloves: just one more thing. How little was needed to take a life!

If you were lucky, death was instantaneous, a flick of a switch producing eternal darkness. If you weren’t, if the fates were unkind, your last moments could be filled with infinite agonies. Everyone was helpless in the face of death. No one could turn back the clock.

The past, if you let it, would imprison you. Each man was serving a life sentence. And yet one quick movement, a simple gesture, could change the world.