Читать книгу Dolores Huerta Stands Strong - Marlene Targ Brill - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

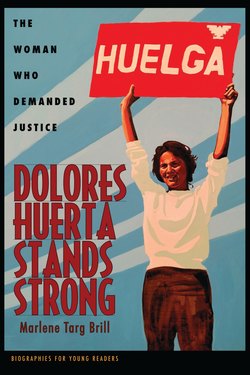

ОглавлениеONE

HARVESTING THE FRUITS OF LABOR

Symbol of Justice

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA is one person on a long list of admirers who agree with Dolores Huerta’s calls for justice. On May 29, 2012, Dolores Clara Fernández Huerta looked on as the president introduced rows of award winners at a special ceremony. Her eyes sparkled. What would the president say about her? She sat up straight. She looked regal dressed in a formal turquoise suit, unlike the work jeans and T-shirts that she usually wore. Today, she dressed like the honored White House guest she was.

Dolores smiled sweetly. The eighty-two-year-old woman appeared calm. But inside, her heart must have leaped with excitement and pride. She’d received plenty of honors over the past few years. But this one came from a president who believed—as she did—in the power of community organizing.

Dolores was one of thirteen honorees: former secretary of state Madeleine Albright, Associate Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, musician Bob Dylan, author Toni Morrison, physician and scientist William Foege, astronaut John Glenn, former Israeli president Shimon Peres, women’s basketball coach Pat Summitt, attorney and civil rights activist John Doar, Girls Scouts founder Juliette Gordon Low, World War II Polish resistance leader Jan Karski, and sociologist and human rights activist Gordon Hirabayashi. Here she sat, among the other surviving awardees. What a journey she had made to get to this place of honor.

Dolores had spent a lifetime fighting for the rights of anyone treated unfairly—people who looked, acted, thought, or felt differently from how others believed they should. Dolores had never done it for the recognition. She fought so that other people could live better lives because of the work that she helped to accomplish. And here she was, about to receive the 2012 Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor that the United States bestows.

When her turn came, President Obama introduced Dolores and listed some of her achievements. He recalled how in 1955 she had left her career as a schoolteacher without thought of how little she was about to earn. Back then, she was a single mother of seven. But she felt called upon to quit teaching in order to improve her students’ lives. She figured she could help her students more by organizing their poor farmworker families to fight for better living and working conditions than by trying to force those young, hungry, and exhausted students to learn.

Dolores wanted community members to stand up for themselves. She decided that she would lead them, be their voice. She pushed the fruit and vegetable growers who hired farmworkers to pay those workers a fair wage, to treat them with respect, and to stop spraying the fields with pesticides while they worked.

Dolores was a tiny woman, about five feet tall, but she was mighty. Many called her fearless. She was driven by the idea that change could happen if individuals banded together. She, like the president, believed that a group that speaks with one voice can achieve more than individuals. President Obama recounted how, with no experience in labor negotiations, Dolores “helped lead a worldwide grape boycott that forced growers to agree to some of the country’s first farm worker contracts. And ever since, she has fought to give more people a seat at the table.”1

President Barack Obama awarding Dolores Huerta the Presidential Medal of Freedom Photo: Rena Schild/Shutterstock

The Medal Presidential of Freedom displays the red, white, and blue presidential The thirteen seal. gold stars represent the thirteen colonies original and are surrounded by gold eagles.

Then Obama thanked Dolores for letting him use her slogan, “Sí Se Puede”—“Yes, We Can”—when he ran for president. He joked about how he never wanted to cross her by using the slogan, the words that advertised her causes, without permission. She was that tough. Dolores smiled.

After Obama fastened the Presidential Medal of Freedom around Dolores’s neck, he bent over and hugged her. Everyone in the room clapped. Dolores beamed.

Dolores had been through a lot over the years—beatings, jail. She had endured time away from her children, miles of marches, and end-less travel. Her family members and neighbors had been treated without respect. She had spent long hours making speeches and protesting in front of companies and government buildings. But over the years, the hard work of battling injustice and her passion for what she believed in had attracted considerable attention. Her notoriety eventually brought many awards, including honorary degrees from universities. Numerous elementary and high schools had been renamed after her. Now President Obama had chosen to honor her with the highest award any American civilian could receive.

THE PRESIDENTIAL MEDAL OF FREEDOM

ON JULY 6, 1945, President Harry S. Truman signed an executive order that established the Medal of Freedom to honor civilians who had contributed notable service during World War II. President John F. Kennedy renamed the award the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963. He expanded the scope of the award to include anyone who contributed extensively to public security, world peace, or cultural or other activities. The award was for individuals who made a difference for others, whatever their field of accomplishment. While some formal awards are given often—to foreign heads of state or for military achievements—only a few people receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom. An executive order calls for the awards to be offered yearly, but that hasn’t always happened. Although the president may take suggestions for honorees, the ultimate decision belongs to the president. Of the 550 recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Dolores was only the second woman of Mexican descent to receive this honor.

To Dolores, however, the greatest prize was the success she had achieved in encouraging others toward a better life. After the ceremony Dolores said, “My most memorable advice from my mother was: ‘When you see people who need help, you should help them. You shouldn’t wait for people to ask.’ When I learned organizing skills, I had an obligation to teach people to come together to fight for what they need.”2

DID YOU KNOW?

Chicano/Chicana, Latino/Latina, Mexican American, or Hispanic? Many people get confused about which term to use to describe people in the United States who are of Spanish-speaking descent—and about whether such labeling is necessary at all. Definitions and how they are received vary, depending on what sources are consulted. “Chicano” refers to someone of Mexican origin who was born in the United States, like Dolores. While some people view the term negatively, because it was first used as an insult, others take pride in the term, noting the work of the Chicano Movement, or La Causa, for its fight for civil rights and better treatment of its people. “Latino” refers to geographical origins, particularly of those countries that were under Roman rule long ago. “Hispanic” usually refers to immigrants from countries that speak Spanish, including Mexico and many other places in Central America, South America, and the Caribbean islands. Both “Latino” and “Hispanic” bother some people, too. And to some, “Mexican American” implies a split identity. More often, someone whose native language is Spanish prefers to be identified by their country of origin, such as Mexican or Peruvian, rather than to be lumped under one vast regional or ethnic term.