Читать книгу Martha Ruth, Preacher's Daughter: Her Journey Through Religion, Sex and Love - Marti Eicholz - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

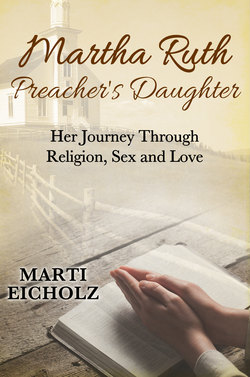

ENGLISH Martha Ruth age 4

ОглавлениеSouthern Indiana offers scenic beauty with its many forests, caves, rivers, and lakes. Scattered across hills and valleys are small towns rich in heritage. English, Indiana, was one of those small towns.

Sitting on top of a hill was a brick house with a white frame church next door. This was our new home. English was our new town.

Highway 237 ran down the hill—or up the hill, depending on which direction you were going—along the foot of it. It was a busy road.

Church members would climb the hill to the services. I wonder now, where on earth did they park? Not on the busy highway; maybe on the narrow dirt road beside the garage. The garage sat at the foot of the hill adjacent to a small grocery store. The church was packed with standing room only, and in good weather people peeked through the windows. Voices bellowing hymns like “The Old Rugged Cross” and “Amazing Grace” echoed through the valley.

The congregation decided to build a new church down the street with extra land for a parking lot. To save money and time, much of the work was done by volunteers from the church and the community. My father worked day and night until he fell off the roof trying to accomplish more than was humanly possible. The work continued, and soon we were having services in our new brick church with plenty of room for worshipers and spaces to park. The entire community was excited.

During this time, I was in a new place up on a hill and without any playmates, so I created imaginary ones. Visitors thought they were real and asked, “How many children do you have?” The answer: “She is the only one.” Well, that had to stop, so I started wishing and praying for a baby. There was a song we sang in church called “What a Friend We Have in Jesus.” I already knew Jesus was in my heart, and now I would call him my friend. I felt comforted. I had a friend. I don’t believe my mother was very excited about the thought of having another baby. She had had a difficult pregnancy and delivery with me, and it was evident that I was enough to handle and try to manage. Then, one day, she started spitting. My mother was one of a few women who have so much saliva they need to spit some out to deal with it. Excessive salivation is called ptyalism or sialorrhea; and while it is unpleasant, it does not affect the baby. Hormonal changes may be the culprit. Nausea also might make one swallow less, causing saliva to build up in the mouth. Ptyalism is more common among women suffering from hyperemesis gravidarum, a severe form of morning sickness, which my mother had. She carried her “brown bag” at all times. A baby was on its way. And I started looking every morning under the dining room table to see if the baby had arrived. My mother was not feeling well, and she was disturbed that my dad was not around much. I am sure I was a handful, but I learned to do “mommy things” like standing on a stool to iron, gathering eggs, sweeping the back stoop, checking on the pigs and rabbits, and walking through the meadow with my dad to milk the cow. We had a little farm up the hill behind the house and the church.

Oh, yes, we had an outhouse. And I do remember the toilet tissue. It was the Sears & Roebuck catalog. No wonder we all grew up to be constipated. Now, living without a bathroom with a toilet, tub, or shower seems totally impossible, but I did it as a child. Millions of humans around the world still exist without a bathroom. I know the experience. I feel badly that many do not know the pleasure of having a clean, private place to go, relax, and relieve oneself of waste. As a child, it was a weekly Saturday night bath in a galvanized tub in the middle of the kitchen. My mother would boil a pot of water, mix it with cooler water, and fill the tub. We would place our bodies in the tub filled with the hot, soapy water and wash ourselves. This was our bath for the week; and there was no lingering, because everyone had to go through the same process. Between Saturdays, we took sponge baths, washing ourselves from a basin of warm, soapy water. Next, we would wash our hair, dipping our heads in the sink and scrubbing our scalps, usually with our homemade, lard-based lye soap. It was reliably rich and full of natural glycerin, which made it a good cleanser that was gentle on the skin. We collected rain in buckets for rinsing our hair. The rainwater was for washing out the soap from the follicles. Our hair was squeaky clean.

Monday was “wash day” (doing the laundry). We used a washboard, a tool used for hand-washing clothing. The clothes were soaked in hot, soapy water in the galvanized tub and then squeezed and rubbed against the ridged surface of the washboard to force the cleansing fluid through the cloth to carry away dirt.

Our house was heated with a wood-burning potbelly stove that sat in the dining room. The open register, an adjustable grill through which heat was released to the upstairs, was next to my bed. The register also gave me access to the discussions occurring after I was sent to bed. If I heard something puzzling, I would yell through the register and ask what was happening. Suddenly, everything would get very quiet.

After a night’s sleep in the upstairs room, a room that extended from the front to the back of the house, we were ready for Sunday. Sunday was a busy day, starting with Sunday school and morning worship, then the noon meal, a nap, youth service, and finally Sunday evening service. A really big day! At the end of every Sunday, if I had been good, I was rewarded with a fifty-cent piece for my piggy bank. I really didn’t know or understand what “good” meant, but I must have been, because I don’t remember a time that I didn’t get to drop the coin in my bank. I loved the sound of it. After collecting any money from my birthday or Christmas, at the end of the year, the money in the piggy bank would be deposited into my savings account. Each Sunday evening, after returning home and receiving my coin, we would sit around the table and have bread or crackers and milk. Dad, as usual, would read a chapter from the Bible, and we each said a prayer before retiring for the night. All prepared for the new week ahead.

My parents started preparing for the baby’s arrival. Dad called his mother, Grandma Hertel, to come and stay with me. Off to Lebanon, Indiana, with Mom. Mom felt secure and comfortable with her mom’s care and familiar surroundings, plus the town had a good hospital. On July 12, 1945, Dad called and announced the arrival of my brother. I talked to my mom, and the first thing she said was, “It’s a boy. What on earth do I do with a boy?” My first thought was, what difference does it make? Boy or girl, the baby had arrived. Furthermore, I had not thought about the gender of this baby. We had never discussed this. What’s difficult about a boy? What’s different?

The newborn baby boy was named James Wesley Hertel. What prompted this choice, I do not know—and does it really matter? Yes, I do think it matters—because in the long term, what does it mean, and how does it affect one’s life?

Later, I discovered that Grandmother Hine was partial to and fond of girls, which I am sure influenced Mom’s first reaction to our new baby boy. I did find it strange that Grandmother’s firstborn was a boy, Robert. Were they afraid of the male genitals? I really think my mother felt overwhelmed. Upon hearing the news, I danced around the dining room, my grandmother giggled, and we hugged each other. Off to bed. Sleeping with Grandma brought story after story until I fell asleep. It was always that way.

August 1945 arrived. August was a big time for the church at large, with a ten-day conference and camp meeting for all the churches statewide convening on the campus and tabernacle in Frankfort, Indiana. There were scheduled sessions for church business, policy-making, and the election of next year’s leaders; dedications and baptisms of newborns; three church services a day with special speakers and singers; eating in the community dining room; and sleeping in simple cottages, rooms, dormitory-style quarters, and tents. Our arrangement was tight: a small room for the three of us and our new baby. My cousin Gloria and her parents—my mother’s sister Juanita and her husband, James Milford Burcham—had a cottage down the street from our crowded room. My mother always thought she was living “hind tit.” Now, whether we could not afford more, or wanted to conserve, I do not know. We called James Milford by his middle name, Milford, since my dad was first in the family, and he was James. Milford was also a minister in the district.

I was Mommy’s little helper. The diapers were washed, so with three diapers in hand and five clothespins, I headed off for Aunt Juanita’s clothesline. Coming out of the building, I noticed a gathering of men working around the front. I passed a lady patrol person and spoke. As I was walking toward the cottage and looking back to watch what the men were doing, all of a sudden the world went black. I thought, “What has happened to the world?” I had fallen into an unattended open sewer. The next thing I remember was standing dripping wet at the hole. Hearing the splash, the men rushed to the hole; and when they saw my hair surfacing, they grabbed it and pulled me up. My head would hurt for years whenever my mother washed, brushed, curled, or combed my hair. It was discovered that I belonged to the minister and his wife, the ones with the new baby, who were staying in one of the nearby rooms. When my mother saw me standing in the doorway dripping wet, diapers in hand, with no clothespins and a half-dozen men, she screamed with fright. The campus nurse was called. The nurse immediately called the local doctor to visit. Fear engulfed the area—fear of cholera or typhoid fever. Both are infectious diseases caused by food or water that has been contaminated with human feces containing bacteria. Each is contracted by eating or drinking the bacteria in the contaminated food or water, which can result in fever, abdominal pain, headaches, vomiting, muscle cramps, and watery diarrhea. The diseases can be spread by a human carrier depositing bacteria in food or water. By the time the doctor arrived, the nurse and my mother had washed me from head to toe with hot, soapy water, and I was wrapped in warm, soft blankets. I sensed the doctor’s concern, and all I could think was, “My, oh, my, I have already given a neighborhood whooping cough. Am I going to give the camp cholera or typhoid fever?” The doctor gave me a shot, and as I fell asleep, I talked to Jesus. He was close by, still nestled in my heart. When I awakened, I was told that the whole camp knew about the incident and that they were praying for me; but I felt comforted because I had already talked to Jesus, who was residing in my heart. I recovered. No cholera or typhoid fever—just a tender skull. The incident was not forgotten. The church community remembered. I became known as “the girl who fell in the sewer.” For years, I would return to the Frankfort Camp in my finest apparel, clothes that my mother had made for the occasion and the coming year. But they didn’t see ME. They didn’t see my beautiful, neat clothes. They saw “the little girl who fell in the sewer.” I no longer felt a part of this church community. I was different. I was set apart. I felt pushed away.

That evening, there it was: the moon. It hung, pale and mysterious, giving me light in my darkest hour. I tried to see the faces in the moon for myself, to feel its craters, and to experience its texture firsthand.

The baby was well and happy.

A couple weeks later, school started.

The school system had no kindergarten, so at age five, I entered first grade. The church, my father, and the Saturday night “street meetings” at the main intersection of the business district became well known. The music and the shouting attracted the townspeople and the country folks. Saturday nights were like a festival. People gathered around the main section of town to shop, stroll, eat, drink, and listen to “The Preacher” and his singers perform.

So when I entered school, everyone knew who I was. I was the preacher’s daughter; and, being five, I was also the youngest. Immediately, I became known as “the baby.” Furthermore, I didn’t look like the other kids. I wore clothing that covered all parts of my body and brown heavy cotton stockings (on special days, I wore white ones). Not looking like the other kids and being called “the baby” and “the preacher’s daughter” didn’t meet my expectations of being accepted, approved of, or appreciated. In today’s world, we would call it bullying, and it was mostly done by my teachers and school officials. I do think they thought they were embracing me, giving me attention, and really enjoying me, but if they only knew how their words cut through and tarnished my soul. I felt I was a big girl and had already done some really big-girl things. I had survived a lot. I was no “baby.”

After a few months of school, December 10th rolled around. It was my birthday. And what a birthday present: Aunt Juanita and Uncle Milford had a newborn, a little girl they named Dorcas Darlene. My cousin Gloria had a little sister. I had just seen Gloria at camp when I was headed to her cottage with the diapers. Gloria was big enough now to be a great pal. She had blond curls and a cute, upturned nose. She wore beautiful clothes. Gloria and her family did not live far from us, so we could meet on holidays and play. I had a playmate, so to speak, at least on occasion. Nine days later came the dreadful news that Dorcas Darlene had died of a respiratory infection. I was so sad. I really did not know about death, dying, and what it all meant, but I did know that someone wonderful and precious was here and then gone before I ever had a chance to see, touch, or hold her. The whole family rushed to Washington, Indiana, to be together and comfort each other. I believe I was the first to break the horrible news to my pal Gloria. Had they not told her? How could they keep this a secret? Grandmother Hine described Dorcas as an exquisite, delicate, angelic, perfect little girl. She had no flaws; she was flawless. I remembered I had a bruised head, olive-colored skin, and other features that Grandmother didn’t seem to care for, so Dorcas was really special. And now she was gone.

Not many days later, it was Christmas. I received the New Testament, inscribed inside “to Martha Ruth, Christmas 1945.”

We were off to visit Grandma and Grandpa Hine in Lebanon, Indiana. My mother’s brother, Robert (Bob), was the firstborn, and he and his wife, Margaret, lived close by. Uncle Bob and Aunt Margaret had a daughter, Margie. Margie was third in line of the grandchildren. Margie had a delayed birth due to the doctor’s arriving late when Aunt Margaret needed assistance. The baby did not come out naturally, resulting in brain damage. Margie had a neurological disorder characterized by epileptic seizures. Margie had epilepsy. Her episodes varied from brief to long periods of vigorous shaking. This was serious. She suffered from developmental delays and intellectual disability. Since the seizures came from one side of Margie’s brain, they led to paralysis in her opposite side, which was noticeable in her dragging one leg and mild speech problems. Margie was the apple of her father’s eye. He adored her. Aunt Margaret and Uncle Bob were inseparable.

Together, they ran a grocery store, managed apartments, assisted the church, and cared for Great-Grandmother Henderson, Grandfather Henderson, and Grandmother Henderson’s two sisters, Nan and Ona.

My first shoes were a gift from Uncle Bob and Aunt Margaret.

Bob had an eye out for his own parents when he started his business of building houses. My first introduction to migrant workers was with Uncle Bob’s helpers and handypersons. Once they were established, the whole family moved to the area and became active participants in the community and in the church. I wondered how they felt about their new lives and about leaving their family, friends, and surroundings behind and starting over.

Well, it is Christmas 1945. We arrived at my mother’s parents’ (my grandparents’) house. Uncle Bob, Aunt Margaret, and Margie were there; the Burchams drove in; and my mother’s youngest sister, Barbara, came. Barbara was a traveling guest singer and children’s worker for special church events, so it was great she was in the area to stop by.

We were all gathered for a holiday celebration. The house was decorated with a tree, wreaths, lights, stars, bells, garlands, ribbons, and beautifully wrapped gifts—a magical place. Grandpa would play Santa Claus, dressed appropriately and with the celebratory “HO! HO! HO!” Early in the year, we drew names so that each of us had someone to present with a gift. It was fun and always a wonderful surprise to discover who my gift-giver was. I still treasure the cuff links my cousin Gloria gave me one year. We had lots of good food, music, storytelling, and gifts, as well as Uncle Bob’s caramel corn. After the meal, when you felt you could not eat another bite, I found there was always room for caramel corn if it was Uncle Bob’s. As a child, Christmas in Lebanon with my grandparents was a tradition.

Family get-togethers were important times for the Hine family. All holidays throughout the year—Memorial Day, the Fourth of July, Labor Day, and sometimes Thanksgiving—were times to celebrate together. The men would rise early on Thanksgiving morning to go hunting for rabbits and squirrels. Grandpa was the only one interested in hunting, but it gave the guys a chance to bond. Grandpa introduced me to the Indy 500. He kept track of the racing families, their skills, and their accomplishments. He enjoyed baseball, and so I grew up with Dizzy Dean, the notorious baseball announcer. I decided most people enjoyed Dizzy Dean more than they did the game itself. Often, we would meet for a potluck. Everyone would bring their own specialties along with the staples of fried chicken, baked beans, and macaroni and cheese. Uncle Bob and Aunt Margaret had a grocery store, so their treats were always the surprise of the day; and you can’t forget Grandmother’s squash pies, sugar cream pies, and angel food cake with no icing (her favorite). Meeting places varied depending on the day of the week and the time of the year. Frequent outings included trips to zoos (St. Louis or Cincinnati), Lafayette Park for its lake and the rowboats, or the local park in Lebanon.

It really didn’t matter. We just enjoyed being together. Gloria and I had such fun times going to animal shows, riding the rides, rowing boats on the lake, swinging, sliding, and running from one activity to another without supervision. Freedom to explore! What a joy!

My grandmother loved her garden and her sunflowers.

My dad thought it was important for the minister to have a nice, all-black automobile so he could assist the local funeral director with family members and participants in the funeral and burial services. For years, we had black cars with black tires.

One day, a letter arrived from Grandmother Hine. It was news about Margie. Margie’s daddy, my uncle Bob, had taken Margie to the grocery store and was holding her while he was grinding meat. A customer stopped by to chat, and as soon as Uncle Bob turned to say a quick hello, Margie tucked three of her fingers into the meat grinder. Those fingers were instantly chewed off from her best hand. What a tragedy! I couldn’t stop sobbing; but soon you realize that no matter what happens, life moves on and takes us with it.

First grade came and went. It sailed by in a complete blur. I do remember the reading circle and the problem that I had with the word “the” (two pronunciations?). The sight method for teaching reading was in vogue at that time, so a foundation in phonics and phonetics was never part of my education in school.

The baby was growing. Our family slept upstairs. My bed was in the narrow passageway at the top of the stairs, with the baby’s bed next to it and then my parents’ bed.

One Sunday morning, my brother was placed in his high chair for a breakfast of cream of wheat. The rest of us were finishing up dressing and preparing to go to church. Everyone was ready except the baby. The baby had not eaten his breakfast. Mom and Dad told him to eat. It was time to go. He refused. Dad got his switch and starting striking the baby’s chubby legs. I thought I would die. I also thought, “There has to be a better way.” I could not watch. All of a sudden, after he ate a few bites, up came the cream of wheat. The baby spewed cream of wheat everywhere. That is the last time my father ever asked my brother to eat something. My dad was the only one not late for church.

The baby sucked his thumb. Many babies and toddlers suck their thumbs. When babies feel hungry, afraid, restless, or sleepy, often they will suck their thumbs. This bothered my mother. She would wrap his thumb in gauze. She brushed a hot lotion on his thumb. Nothing seemed to work. I thought, “Why not just hold him, rock him, sing to him, tell him how much you love him, hold his thumb, and encourage him not to put his thumb in his mouth? He will understand.” I don’t remember when it stopped.

One evening, my father had gone across the street to comfort the Bennett family. Mr. Bennett was old, frail, and dying. My mother and I were home alone with my brother, and my brother was ill. His fever kept rising. My mother was worried and fretful. I noticed that when people are worried and fretful, they just run around in circles. My mother was running around in circles. Her mind was so full, so confused. She needed my father, but Dad was busy. I bent over my brother and whispered to Jesus. Jesus was close by. He was in my heart. My mother kept taking temperatures, and I kept leaning over the baby, my brother, putting a cool cloth on his forehead and whispering to Jesus. By the time Dad got home, the fever had broken. Mr. Bennett was gone.

After the baby started walking, he ran, chased, and took charge. He had no fear. I was five-and-a-half years older than him, but that made no difference. He was a wild one. And he would run you down. I still have a scar on my face from the time he flipped my chair over, causing me to fall and puncture my lip.

I began sneezing, I had a runny nose, and my voice grew muffled and nasal-sounding. I had so much congestion that I had difficulty breathing through my mouth. My breathing was noisy, and it became a snorting sound in my sleep. I developed a cough and a sore throat. The doctor confirmed that I had an inflammation, and once that inflammation was under control, they would remove my tonsils and adenoids. A date was set for the removal. Well, this sounded painful and unacceptable to me, so I headed up the hill, walked through the meadow, and talked to Jesus. He was still nestled in my heart, and the song we sang in Sunday school was “Jesus Loves Me This I Know for the Bible Tells Me So.” Jesus loves me. Does he want me to go through this? Is there a reason why I should? The day came for the removal. We were prepared, and I had been promised an ice cream after it was over to ease the hurt. The doctor did a final check and stated there were no tonsils to remove. My tonsils were gone. They had disappeared. This was a miracle to me at this time in my life. I learned later that tonsils atrophy and waste away when you have severe sore throats or tonsillitis. To put it not so sensitively, they rot out a little each time you have tonsillitis until nothing of them remains.

The Apple family had a farm and a sawmill not many miles from the church. On one occasion, I visited my friend Diana, who was always dreaming of becoming a movie star. Diana was a natural beauty, and she didn’t mind that I was younger. We still had fun. It was a busy time for the farm, and the sawmill was active. Diana and I walked through the woods to watch the action.

The guys saw us coming and decided to have some fun, so once we got close, they fired off the engine whistle. What a blast! It sounded like an explosion. Being afraid of noise, I started running wildly, not knowing where to go. I ran underneath a huge dump truck to escape to the other side. Thinking I was safe, I reared up and hit my head, creating a hole in my forehead. Blood gushed everywhere. The gash was washed, cleansed, medicated, and stuffed with gauze. The scar on my forehead still lives with me. No more sawmill trips!

I did return to the Apples’ farm, not only to visit my friend Diana but also to pick strawberries in the summer. I loved competing to see how many baskets I could fill. My first earnings came from picking strawberries on that farm. I was so happy and proud of my accomplishments.

One fall, my dad opened a box chock-full of boxes of Christmas and all-occasion cards. He proposed the idea of presenting his collection of samples to friends, family, and neighbors, taking orders, and making some money. I was all in. I spent time examining the cards in each box, checking their prices, and learning the procedure of taking orders, and then I was on my way. I remember vividly my first afternoon out in the neighborhood going door to door up and down the hill, talking to people, sharing the cards I thought were the prettiest, and writing orders. It was dark before I returned home, but I was tickled pink with a fistful of orders. This was my second source of income. For years, it was the same every fall: studying the new collections, presenting samples, and writing orders.

Yearly, a group of church members would come to the house, and the men would butcher one of the pigs. The wives would help my mom with preparing food for the hungry gang. This was always a long day of cleaning, carving, and preparing the meat for some months of good eating. It did not take me long to know that the tenderloin part was my favorite. I knew early on the good things in life. Brains and eggs would grace our table. Headcheese was a dish made from the head of the pig. The head was washed and scraped clean, the bristles shaved or plucked. After splitting or quartering the head, it is simmered in a large stockpot until the meat is so tender that it falls off the bone. The skull is removed from the cooking liquid and allowed to cool, and then the meat is picked off the skull and chopped. Seasonings and vegetables are added along with the strained cooking liquid. This mixture is poured into pans or molds and refrigerated. When it is set and solid, it is ready to be served. Sometimes it is served cold and sliced, and other times it is lightly fried.

The parishioners were good to us. They invited us to their homes for meals, sharing the fruit from their gardens and heavily laden trees. Bushels of fruit, green beans, tomatoes, and other vegetables were canned for the winter months. Late in the season, you could find bushels of reasonably priced fruits and vegetables for canning at farmers’ roadside stands.

Once a year, we would take a trip to Austin, Indiana. Austin had a warehouse that would open to the public to rid its stock of dented cans at a few cents each. We would fill the car with boxes of dented cans, an excellent resource for supplementing our food supply.

We had our cow for milk and churned our own butter, the garden for fresh vegetables in the summer, chickens for eggs and eating, as well as rabbits and pigs. There was no need to go to a grocery store other than for a few items like flour, salt, pepper, sugar, baking powder, baking soda, and Crisco.

A baptism service was scheduled for all new members. The church did not have a baptistery, and the belief was that a person should be fully immersed in the water, not just sprinkled with it. I was on the list of participants to receive this Christian sacrament of rebirth, and my time came. Everyone sang the hymn by Robert Lowry, “Shall We Gather at the River?” My father waded out into the water. All I could see was his head sticking up. Names were called, and each person walked out into the water. My father greeted them and quoted something (I guess it was from the Bible), and then immersed them into the water. I watched as they came up dripping wet and shaking from the chill. I decided this was not for me, so I ran through the woods and waited while my name was called, hidden behind a tree, and then quietly walked to the car. After the ceremony, my parents and I drove home in silence. Being baptized was never, ever mentioned to me again.

It was rare that my parents would go away without me, but when they did, Grandmother Hertel would come. She always had a handful of books, which I loved. It seemed something unusual would always occur. The happenings were mostly self-inflicted, because with her there was a sense of freedom, relaxation, laughter, and “just plain fun.” One of these times, I decided to go up to the meadow and pick wild blackberries along the fence rows. I came home with a few berries in my basket and my body full of hard, red, infuriating, itchy chigger bites. These were summer pests, mites or bugs that would suck your blood and cause intensely irritating itching. I had more chiggers than berries. Chiggers loved the blackberry habitat. Grandmother wrapped me in cool, wet towels, and we slept on the floor. Throughout the night, she replaced the cool, wet towels to comfort me.

Another time, I came down with the mumps and began hallucinating in the middle of the night. Grandma was a great nurse. She had the right touch to comfort, cuddle, and help make the worst situations better. There was a trip, and Grandmother could not come. Let’s be realistic: She lived in Fort Wayne as a working woman; and even though she came by train on Granddad’s passes, this was still a chore for her.

On this one occasion, I was sent to the Enlows’ farm. The Enlows went to our church. They had an older daughter who lived away from home, and she had come home for a visit. Lucky me! Sarah and I shared a small, cramped room upstairs. It reminded me of a storeroom or a small attic. That did not matter. Sarah shared stories of her life, read to me, and played music, and one day she took me for a walk through the woods. We came upon a flowing creek. Quickly, we removed our shoes and stockings and were tickling our toes in the water, jumping from one stone to another. Finally, we sat down by a tree to savor the stunningly beautiful view. It was so quiet and tranquil. As we were returning to the house, all I could think about was revisiting this walk, the flowing stream, and the sense of peace. And it happened. Sarah’s mother prepared a picnic lunch so we could have another outing in the woods. Sarah took her guitar, and I carried the lunches. When we arrived at the stream, we tossed off our shoes and stockings, jiggled our toes in the water, and ate a bite, listening to the quiet and savoring the scene. Sarah began to strum, stroking her instrument lightly with her fingers. All of a sudden, her beautiful, light, delicate, clear voice gave me my first taste of “Cool, Clear Water.” That was where we were: in the midst of cool, clear water flowing between our toes.

“The shadows sway and seem to say

Tonight we pray for water…cool, clear water

And way up there He’ll hear our prayer

And show us where there’s water…cool, clear water”

I don’t remember all the words, but I do remember “cool, clear water.”

It was cool, it was clear, and it was water. As I watched, listened, and felt, I thought, “This beauty must last forever.” And it did in my mind.

The church was blossoming. My dad was getting recognition in the district. The district superintendent, Melvin Snyder, was a frequent visitor, and we always remembered his love of buttermilk. General officials in the church were guest speakers.

One in particular was Paul Elliott. Dr. Rev. Elliott took a liking to me. It was a defining moment in my childhood when he asked my parents if he could adopt me. Apparently, at the time, he and his wife were unable to have children, and they would be able to educate me. The point I remember was, “We will give her a good education.” What impacted me is that I really believed my parents gave his offer serious consideration. I always wondered why, and in my mind were a number of reasons; but I really didn’t want to know, so I never asked. As I reflect back, did he see a curiosity, a vivid imagination that was being squashed? Did he think my parents were poor and always going to be poor, so my education would not be affordable? Did he notice or sense a conflict between me and my mother? Was he attempting to save a really troubled child? What was the motivation? I will never know.

I must have been a handful. But was I really? Or was it like I thought at the time—that I was just living life? Exploring, testing, discovering, questioning, and attempting to make sense of the world that surrounded me? I had not long before experienced a few minutes in time wondering, “What had happened to the world?” Now that I had a second chance to try and find out about this thing called “the world,” I wanted every taste, every smell, and every sight and sound. I wanted more and more.

When family, friends or visiting dignitaries came, it was fun and a joy to take a day trip to Marengo, Indiana. Traveling less than 10 miles we visited the most incredible cave with mineral deposits and beautiful stalactites and stalagmites. Marengo Cave was discovered by two school children in 1883. A brother and sister were playing in the thick wooded grove with undergrowth of vines and ferns. They stumbled and fell into a sink hole and were attracted by an opening, leading to the discovery. Tours commenced soon after. It was an awesome sight and a thrilling experience sharing this underground wonder.

The lady who owned and operated the nearby grocery store, June Walts, became close friends with my mother, and they remained so for the rest of their lives. June’s husband, Bob, taught school in Grantsburg a few miles up the road. Twighla, their daughter, became my close friend.

We did not attend school together. She attended school in Grantsburg, where her dad taught. Twighla and I would play together on non-school days and during the summer. One day, after Twighla and I had finished a game of checkers and I was headed home, I stopped to glance at the candy bar case. I asked June if I could have a candy bar and pay her later. She gave me my Baby Ruth, and I was on my way. Remembering seeing my mother take a bill from my father’s wallet, I was thinking I could take a coin from my mother’s purse. I ran upstairs, pulled open the bottom dresser drawer, and took a dime from my mother’s coin purse. I closed the drawer and ran downstairs, not realizing how much commotion I had made and how much attention I had drawn to myself. I was out the front door and down the lawn when I suddenly heard a loud call: “Martha Ruth, where are you going?” My little hand was gripping the dime tightly. I answered, “Nowhere.” The reply: “Oh, yes, you are! And what do you have in your hand?” Dropping the coin (thinking it wouldn’t be noticed), I lifted my hands and said, “Nothing.” “What dropped on the ground?” I was caught. And it was not a happy catching. I was marched into the house. My father got his leather belt, and I was ordered into the back bedroom. My father and I had quite a contest. He was trying to whip me, but I was dancing and jumping from side to side trying to avoid his lashes. He finally wore me out, and I had to lie down and take it. It was soon over. Afterwards, the discussion began, “This hurt us more than it hurt you.” I KNEW BETTER! This was silliness. I hadn’t heard anything so stupid in my life, and I wondered for days, “Isn’t there a better way?” “There has to be a better way.” No one talked about it. Why didn’t someone say, “Let’s work this out together”? It made no sense. Candy bars never tasted good again.

I do believe my mother began to think that I was really trouble and that I was going to wreck the whole family. It was easy for her to get nervous and upset. I have no idea what on earth ticked her off, but out of the blue, she decided I should be sent to jail. The jailhouse was on the opposite hill. So, in a fit of rage, she tells me she is calling the jailhouse to have someone come and pick me up. I can still hear myself agonizing, fighting with her, and trying to grab the phone away from her clenched fists. I decided I had better have a quick talk with Jesus, so I yelled, “Jesus, help!” That’s all I remember. A little later, as I was taking an afternoon nap, the song “Jesus Loves Me This I Know” came floating through my mind. I could feel no other love but the love of Jesus. I was glad that I had invited Jesus into my heart, because I needed him. It never occurred to me to doubt whether my heart was spacious enough to accommodate a person like Jesus. It seemed to me a pretty grand thing to have Jesus living in my heart.

I had enjoyed so many good and beautiful things in my life, I figured I must observe and witness some ugly ones. Doing so awakened me and exposed me to things I didn’t quite understand. Pondering over these matters, I found them difficult to comprehend.

After first grade, there were two grades in each classroom. In fourth grade, musical instruments were introduced. I had already started piano lessons before entering school, and I was doing well. I tried to mimic the church pianist, who could play all the runs and fly his fingers up and down the keyboard. I thought, “Someday, that will be me.” My mother played the accordion, so I thought that I would probably continue in her footsteps; but the instrumental music teacher and other advisers thought that the accordion was too big for me. I appreciated their insight. I was introduced to the cornet, a brass instrument very similar to the trumpet but distinguished by its conical bore, compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The cornet became my musical instrument to study for the band. I believe everyone noted a lot of “hot wind” blowing around that could be put to good use.

My mother’s sister Barbara married her sweetheart, Max Hamilton.

The three cousins, Gloria, Margie, and I, participated in the wedding. I sang “I Love You Truly.”

Max sang to his bride as she came down the aisle. It was very special.

The only sad thing about this gloriously happy day was that my grandparents refused to accept this union and did not attend the ceremony. What a blow! This introduced me to the word “acceptance,” and I began my search for its meaning. Were they not willing to bring Max into the family? Was he not satisfactory or good enough? What was the problem? My aunt Barbara was a mature adult. She traveled all over spreading the message of Jesus, and she supported herself. Thinking about “acceptance,” when I asked Jesus to come into my heart, it never occurred to me that he might take one look inside and say, “Sorry, this isn’t quite what I had in mind. This is not the kind of place I want to live.” Both Max and Barbara were involved in church work, and they made an ideal couple. They had the same goals and ideals in doing God’s work. They were a sensational musical team. My mother used Aunt Barbara as an example for me to aspire to. Everything about Aunt Barbara—her voice, her musical capabilities, her storytelling, her sweetness—was my mother’s ideal for me. Aunt Barbara was great, but my mother didn’t look at me and encourage me to be myself and the best me I could be. She never did. I didn’t listen and missed my opportunity. I also learned that parents, the church, the community, and a host of others like having control; and when you don’t conform to them, they can pout, retreat, ignore, and withdraw. Where is the love? I was so happy and proud that my aunt Barbara stood her ground, married the love of her life, and continued her calling.

Uncle Max and Aunt Barbara traveled and shared God’s message through song. They created three beautiful children.

The family formed a sensational musical group for sharing God’s message. They retired as a group when Phil, the oldest, entered high school; Steve, the middle child, entered junior high; and Susan, the youngest, entered first grade. They settled down on Grandfather Hine’s farmland and built a new life. Max worked as a postman in Indianapolis, the children were enrolled in school, and Max and Barbara continued performing in churches all over the area.

Back to English and my childhood, there was a movie theatre in town. My church didn’t believe in going to the movies, so I didn’t give the theatre much thought until “Black Beauty” was showing, and my teacher decided our class would attend. For this field trip, you were not allowed to go without permission from your parents. “Black Beauty” was the story of a widower trying to raise his motherless daughter, Anne. He presents her with a colt, Black Beauty, with the hope that by learning to discipline the horse, she may learn to discipline herself. I thought perhaps I could learn something from this, but I was unable to attend. It was ridiculous to read a book but not be able to see it in pictures. My class walked from the school to the theatre, and that was okay. Then, the class stopped and entered the theatre, and I waved goodbye and walked home alone. Yes, I was right. I was different. I did not fit into this group.

The church’s activities were gathering places for the townspeople, farmers, and landowners in the surrounding area. One of the most powerful families was Seth Denbo’s. Mr. Denbo owned the lumberyard and the car dealership across the highway from our house. He had a huge hatchery and breeding farm for producing quality purebred poultry and eggs. He farmed crops of all kinds. Late one afternoon, there was a crackle in the air followed by the sounds of police sirens and a racing fire engine. All those noises made me want to hide. I was frightened by the sounds and the smell; and when I looked out the window, what I saw was horrifying. The lumberyard was ablaze. It was terrifying to realize the possibility of a spark causing more fires. Glued to the window, I could see sparks falling on our lawn. The smoke, the smell, and the sight of it all were suffocating. Then I noticed the full moon. I was fascinated by the moon, my never constant yet always faithful friend, hovering over me and chasing away my fear. Sleep would not come. I was consumed. Finally, weary beyond words after hours of being stuck to the windowpane, I looked up at the moon, spoke to Jesus, and fell asleep.

Seth Denbo was a strong supporter of the church, a powerhouse in the community, and a major force in state politics. He was a conservative Republican, and he fought hard for southern Indiana’s needs, issues, and concerns. He lobbied in Indianapolis for the people living south of Highway 40. He was a guiding light for those who hated Indianapolis’s running of the GOP. It was felt by many that Indianapolis favored the northern part of the state. Even Grandmother Hine favored northern Indiana. She lived only a few miles north of Highway 40, but still her allegiance was there. Of course, her influence did not help my mother, who was constantly trying to please her own mother while living in the south. Suddenly, Seth Denbo quit the church. Mr. Denbo and my father had been close. They worked together for the good of the church, they supported each other, and now he was gone. What happened? I was shocked. I missed going out to the farm. I missed the kids, the animals, the whole scene. My mother began to snoop, pry, and investigate to discover what was going on and what had happened. This was the beginning of my father’s shutting down, sheltering himself, and not discussing things with my mother. Well, this did not sit well. He undoubtedly was fearful of what hurt, damage, or stress the truth might cause. If they ever knew what happened between Mr. Denbo and the church, I never found out. As a child, I always wondered what could happen to a faithful, loyal, and dedicated servant of Jesus who just suddenly “quit.” I missed him and his bald head. I have often thought about him, and I still miss him.

We were in our fifth year at the church in English. It was traditional to have the church elections in late spring. New local church officials would be selected first, and then came the vote on the minister. The yearly election was always an anxious time for our family. How many yeses and how many noes? Did they like us? Who might reject us? What nonsense! Really, had we served them well? Were the spiritual needs and expectations of THEIR church being fulfilled? It was their church. A minister comes and goes. Of course, hindsight is always better. At that point in my life, it was a matter of wondering whether they “liked” us. Well, the vote was taken. After the final count, my father, meaning the family, had been voted OUT. We were to move at the end of August and be at our next parish before school started.

This was the beginning of a new mindset in our family. We wondered, “What will the people think?” This thought permeated everything we did or said. Everything revolved around the premise of pleasing others. That is not a comfortable way to live life. You never have a good, sound feeling about what you really think, believe, or feel. It is important to live in an environment in which there is no fear. We became afraid of living—afraid of what people thought. Much of my life in English had been so beautiful. Much of it had been so extraordinarily lovely. Now, I could feel an increased sense of fear and anxiety, especially from my mother.

August would soon be here, and with it our yearly conference and camp meeting in Frankfort. My new clothes were being prepared, and I stood up straight while the hems were being pinned. News arrived that attendees needed to be cautious and that the conference could be scaled down because of the fear of a widespread polio epidemic. It struck so severely that, on July 30th, the Board of Health in Portland, Jay County, Indiana, demanded that all public events be closed and shut down. Kids were not to go outside to play. Polio, often called infantile paralysis, was peaking. Polio was an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus, causing fever, headache, vomiting, diarrhea, neck stiffness, and pain in the arms and legs. A mild case could last a few days. A more severe case, when the infection inflames the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord and destroys the motor nerves, could take up to two years to recover from and in some cases caused permanent paralysis. Every summer, there would be a serious outbreak in at least one part of the country. This summer, the Midwest—and specifically Indiana—was identified as being at risk. My parents decided to go to the conference, but they stayed with my grandparents who lived 17 miles away from Frankfort. My brother and I stayed home, and Grandmother Hertel came. That was fine with me. I was fed up with going to camp and being asked about falling in the sewer or hearing, “She’s the little girl who fell in the sewer.” I guess they had nothing better or more interesting to talk about, and what a shame that was. I thought it was cruel and ugly.

My parents returned, and we immediately started preparing for our transfer to Columbus, Indiana. We were moving north and closer to the Hines, which pleased my mother.

Our last Sunday in English had a pleasant surprise. It was the custom of the church to have a treasurer’s report at the end of the Sunday morning worship service. Even as a child, I thought it was extremely strange to end a worship service with a treasurer’s report. The church treasurer would report the income and the expenditures. Ten percent of the balance would go to the minister. This was his salary for the week. It varied. It was uncertain. Thankfully, we did have our housing covered, so there was no worry of becoming homeless. This Sunday, the minister’s share was the greatest ever. My memory fails me, but it was either 75 or 90 dollars. WOW! That was great! This was two or three times the usual amount, and after we were VOTED OUT. Maybe someone really did like us and thought we were okay.

It was a short time before our departure, so I had to rush to see my friend next door. The couple who lived down the hill from our side yard had a boy about three years older than me. He was a foster child—an orphan they had taken in or an adoptee. I never knew which, but I understood that the couple could not have children and that this boy was living with them. We had played together on occasion. When I told him I was leaving, he told me he would get some kites and to meet him up in the meadow the next afternoon. I really didn’t know about kites nor had I ever seen one. But the next afternoon, we met in the meadow across from the opposite hill—the hill that had the jailhouse. He began handling his kite, and he gave me one. I was to listen to and follow his instructions, and then my kite would fly. The conditions and the winds were perfect, and our kites soared. I felt like I was aboard a kite flying through the air, away from here and on to my new home. The song “I’ll Fly Away” rang through my being.

“I’ll fly away oh glory, I’ll fly away

When I die hallelujah by and by, I’ll fly away

Just a few more weary days and then, I’ll fly away

To a land where joy will never end, I’ll fly away

I’ll fly away oh glory, I’ll fly away”

It was memorable.

Soon, we were packed, the truck was loaded, the house was swept clean, and off we were to stay overnight with the Enlows before our trip to Columbus. The Enlows took good care of us. We were tired and weary, but sleeping on the farm with the windows open wide and breathing the fresh country air was wonderfully peaceful. At the beginning of sunrise, I could smell the fried chicken. Yes, we had fried chicken and homemade biscuits and gravy for breakfast. It was extraordinary. My only regret was not being able to run through the woods one more time to check on the quietness of the flowing stream as it bubbled over the stones under a ray of sunshine shining through the trees. I could see and feel it in my mind. The memory would always be there. I would be able to return any time I needed solace and comfort, or just for the plain joy of it.

Doll and Olas Hine were proud of their family, all ministers in their own ways.