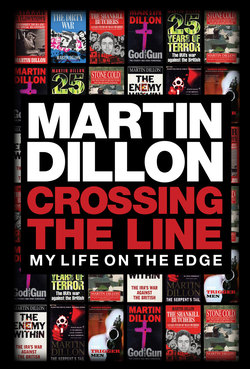

Читать книгу Crossing the Line - Martin Dillon - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

Journalism is apparently the first draft of history so presumably the journalist’s memoir can be the second. If Martin Dillon’s remembrance here achieves equivalent significance to his original reportage, then this book should be of historical import.

In the 1960s the half-century-old partition of Ireland into two states, one post-colonial, the other neo-colonial, began to sunder. Once more, and to the great chagrin of London and Dublin, the Irish problem had to be solved again.

Northern Ireland was being ambushed by a series of forces past and present; the Vatican Council’s ecumenical movement impacted on its historic Protestant fundamentalism; the new era of foreign direct investment began to undo its traditional discriminatory worker practices; the rising Catholic birth rate was threatening its gerrymandered artificial majority and, most significantly of all, there was the impact of the 1947 Education (Northern Ireland) Act.

This act, which created free second-level education, in time overwhelmed the old Orange state, unleashing a first generation of middle-class professional Catholics who, unlike their fathers and grandfathers, were not prepared to take no for an answer.

It all began with street protest but very quickly the guns came out and, as though out of the history books, stepped the old ghosts of Republicanism and loyalism. It was planter versus Gael – twentieth-century style – with Molotov cocktails, Armalites, Semtex and ‘Romper Rooms’. Few knew then that a thirty-year conflict was beginning.

The young Martin Dillon had just got his first typewriter when the first stones were thrown. For the decades following, he was to both live in this battlefield and report it. This memoir is suffused with encyclopaedic small-print local knowledge and has all the energy and urgency of a journalist who had no home to go to at closing time since his home was also in the trenches. Dillon’s reportage came as much from his Belfast-born DNA as from his journalistic instincts.

As the troubles grew, Belfast soon had its colony of journalists – most were brief visitors – but for Dillon, merely counting the stories in and counting them out would not satisfy his appetite. He began to poke and peep into the hidden places and the secret practices that all of Northern Ireland’s many armies – legal and illegal – were hiding. His old contacts book should go to some journalistic museum.

It is no exaggeration to say it but there were times, especially in the 1970s, when after dark some of the streets in Belfast were among the most dangerous places in the world. Apart from anything else, here was a journalist who took huge risks in asking the difficult questions.

In the end, as Dillon had always suspected, one day he would have to pack his typewriter and notebook and leave before they came for him. Even for veterans like him, the delicate balance between getting the story and not getting yourself killed was a daily and frequently exhausting calculation. Judging from this memoir, he got out just in time.

From the very beginning, there were two simultaneous and parallel wars ongoing in Northern Ireland; the visible one that was all over the tea-time news, and the invisible one that would sometimes emerge briefly, leaving behind tantalising fingerprints and glimpses of hidden agendas.

Here was a battlefield where the politicians ceded control to the spooks, where the state’s writ barely ran, and about which the less the good citizens of the liberal democracies were supposed to know, the sounder they were supposed to sleep in their beds at night. This was Dillon country and as he followed its mysterious trails, he was among the first to raise the deeply troubling question of the legality of the state’s dirty war.

At their very best, journalists are worker bees, hewers of information and carriers of facts, especially the very few who will not take no for an answer. They should be pains in the arse for any establishment, and Dillon was one. You’ll find him all over these chapters, the hack armed only with a pen and facing the high walls of official denial.

In his 1990 book The Dirty War, Dillon had opened the first ever window on the secret counter-insurgency war that the British state fought in Northern Ireland. This was a campaign drawn on classic Brigadier Frank ‘Kitsonian’ parameters that, even to this day, is still reluctant to give up some of its ghastly secrets.

Even today as more and more secret agents are uncovered and led out, blinking into the sunlight, or as veterans begin telling their stories for the first time, the visible extent of the dimensions of the secret war grow year by year. Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about the truth is that eventually, however long it takes, it will always come out.

But across thirty years, with its vast network of agents and intelligence agencies, the complete story of the dirty war remains to be told. Shoot-to-kill; the running of double agents; the manipulation of paramilitary killings; the secret importing of weaponry; the unexplained deaths; to this day the incident files remain bulging with unanswered questions.

Within that extraordinary hall of mirrors, it is to Dillon’s unique credit as a journalist that he was among the first to begin lifting the stones and looking underneath. It was difficult and dangerous work, even the journalistic establishments were timorous near this terrain and Dillon’s courage and dedication should be recognised.

Dillon was also the scribe who revealed to us some of the most deprived human animals who ever existed, in his 1989 book The Shankill Butchers. His telling of how a group of bog-standard, working-class men in a United Kingdom urban jungle could spend their evenings in drinking clubs featuring their unique floor show of the torture and throat-cutting of their Catholic neighbours still makes the blood run cold. In some places, such a group might constitute a club for playing darts or for pigeon racing, in Northern Ireland here was a club for the enjoyment of serial killing.

Lenny Murphy the Shankill butcher who slashed his victims’ throats; Michael Stone the loyalist paramilitary who attacked a funeral with hand grenades; Freddie Scappaticci the double agent in the Provisional Irish Republican Army, known by the codename Stakeknife: Dillon’s cast of villains across this memoir takes some equalling.

There are other chapters, too, on his childhood, his failed religious vocation and a tender memoir of his famous great-uncle, the artist Gerard Dillon.

Gerard’s brush left behind indelible images for us of his era, his great-nephew Martin’s pen has drawn hugely significant questions marks across another era. The artist with his colours, the artisan with his words, the Dillon DNA has hugely enriched us all.

Tom McGurk, August 2017