Читать книгу Ghost Towns - Martin H. Greenberg - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

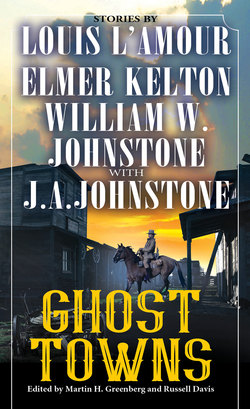

The Ghosts of Duster William W. Johnstone with J. A. Johnstone

Оглавление“All I’m sayin’ is that I never promised to marry the gal. Hell, you know me better’n that, Bo! Do I look like the sort o’ fella who’d want to get himself tied down by apron strings?”

Bo Creel glanced over at his best friend and said, “You look like a fella who’s damned lucky to be alive. That lady’s brother had a shotgun, you know.”

Scratch Morton grinned. “I know. For a minute I figured I’d be pickin’ buckshot outta my backside until next week.”

The two men rode along the base of a ridge in West Texas, being careful not to skylight themselves. They had lived long, eventful lives on the frontier and knew that although most of the hostiles were either on reservations or had gone south into Mexico, it was still possible to run across a band of renegade Apaches in this vast, rugged area west of the Pecos.

Bo and Scratch were of an age and had been best friends for decades, ever since they’d met as youngsters during Texas’s war for independence some forty-odd years earlier. They’d been on the drift for almost that long. They didn’t think of themselves as saddle tramps; they were just too restless by nature to stay in one place for too long. Although they had been just about everywhere in the West, they liked to wander back to their home state of Texas every now and then. Once a Texan, always a Texan—born, bred, and forever.

Scratch was a handsome, silver-haired dandy in a fringed buckskin jacket and cream-colored Stetson. The twin Remington revolvers on his hips had ivory handles. Bo, on the other hand, looked like a preacher in a sober black suit and flat-crowned black hat. His Colt had plain walnut grips.

The weapons were similar in one respect, though: they were well used. Bo and Scratch had a habit of running into trouble. Scratch was just a natural-born hell-raiser, and Bo couldn’t help but stick up for folks who were outnumbered and outgunned.

They were in El Paso when Scratch made the acquaintance of a comely maiden lady. One thing led to another, and although the lady was still comely, she wasn’t quite a maiden any longer. She hadn’t made any complaints about that change in her status, but her proddy, overly protective older brother did, so Bo and Scratch had left the border city rather hurriedly.

Since then they had spent a couple of days riding east and were still a long ways from getting anywhere. This part of Texas took awhile to ride across. Bo had done pretty well in a poker game before their hasty exit from El Paso, so they had enough money to buy supplies. The problem was finding a settlement where they could pick up some more provisions.

“If I remember right,” Bo mused, “there’s a little town not too far from here. Name of Duster, I think. We ought to be able to buy a few things there.”

“I hope so,” Scratch said. “Otherwise we’re gonna get mighty tired of eatin’ jackrabbit by the time we get to San Antonio.”

“Tired of it, maybe, but at least we won’t starve to death.”

The ridge was to the north, on their left hand. Beyond it rose a range of jagged mountains, the sort of peaks that jutted up out of the desert with little or no warning in this part of the country. To the south swept a vast, brown, semiarid plain that ran all the way to the Mexican border. A few waterholes were located along the base of the ridge, Bo recalled; otherwise this was mighty dry country.

They rode on, and as it became late afternoon, Scratch asked, “How far’d you say it was to this Duster place?”

“Ought to be there any time now,” Bo replied.

“Then shouldn’t we be seein’ smoke from the chimneys?”

Bo rubbed his jaw and frowned. “Yeah, you’d think so. Maybe no one’s cooking right now.”

“I was hopin’ for a nice hot supper, followed by a cold beer.”

“Well, don’t give up hope just yet. Maybe I’m wrong about how far it is. I’ve never been there, just heard hombres talking about the place.”

A few minutes later, though, the settlement came into view. Bo and Scratch reined their mounts to a halt and stared at it in surprise.

Or rather, at what was left of it.

Some sort of catastrophe had happened here, that much was obvious. A number of the buildings had been reduced to flattened, scattered piles of lumber and debris. Other structures leaned at crazy angles. Only a handful of buildings were upright and relatively intact. At the northern edge of town, nearest the ridge, was a huge mound of bricks and lumber. It looked like a large building had collapsed in on itself.

“Good Lord A’mighty,” Scratch said. “What in blazes happened here?”

Bo’s eyes narrowed as he studied the landscape both north and south of the ruined settlement. “Look yonder,” he said, pointing. “Below that notch in the ridge.”

The roughly V-shaped gap he indicated had a deep gully below it, running arrow-straight toward the town. Scratch frowned at it and then said, “That ain’t natural, is it?”

Bo shook his head. “I don’t think so. Looks to me like there must’ve been a mighty big thunderstorm in the mountains. The rain all washed down behind that ridge and busted through at a narrow place. That was like a dam breaking. The flood carved out that gully and came thundering down until it smashed right into the settlement.”

Stretch gave him a dubious glance. “You sayin’ it rained enough to do that, here in West Texas? Hell, this is one of the driest spots east of…well, east of hell.”

“Most of the time that’s true,” Bo agreed. “But every now and then it comes a big cloud. I’ve heard more than one story about folks drowning in the desert in flash floods.”

“Yeah, but only when they was dumb enough to make camp in an arroyo or some place like that.”

Bo pointed again. “When that ridgeline crumbled, the water formed an arroyo, and it was just like pointing a gun at Duster. I don’t know if everybody in town was killed in the flood. Seems unlikely. But the survivors must’ve packed up and left, because I sure don’t see anybody moving around.”

“No, the place looks to be deserted, all right,” Scratch admitted. He let out a groan. “So much for buyin’ supplies here.”

“Maybe we can find some the citizens left behind.”

“If we do, they’ll likely be rotted from bein’ water-logged. Folks probably took anything that was any good with them when they pulled up stakes.”

Bo knew that Scratch was probably right about that, but it wouldn’t hurt to have a look around. He said as much and jogged his horse into motion again toward the settlement.

Scratch rode alongside him and asked, “What do you reckon that pile o’ bricks was? Don’t see too many brick buildin’s out here. Mostly adobe and some lumber.”

“I don’t know, but it was a good-sized building. I’m surprised it collapsed. Looks like it should’ve been sturdy enough to stand up even to a flood.”

“Maybe a cyclone come along and flattened it later.”

“Maybe,” Bo said. “We’ll ride over and take a closer look after we—”

He stopped short and jerked back on the reins as a ragged scarecrow of a figure dashed out from behind one of the leaning buildings and ran toward them, screaming.

Scratch cursed and slapped leather, filling his hand with the butt of an ivory-handled Remington. But as the gun came up with blurring speed, Bo reached across with matching swiftness and clamped a hand around the barrel.

“Don’t shoot,” he snapped. “That hombre’s not attacking us.”

It was true. The man was too scrawny to constitute a threat anyway, even if he had been hostile. As he loped forward and waved his sticklike arms over his head, his pitiful screeches became words that the two drifters could understand.

“Are you real? Oh, dear Lord, are you really there? Please be real!”

“Please be real?” Scratch muttered. “What in blazes does he think we are, ghosts or somethin’?”

Bo glanced around at the abandoned, devastated settlement. “Good place for it, don’t you think?”

Scratch couldn’t argue with that.

The scarecrow man stumbled and fell to his knees as if the last of his strength had deserted him. He pawed at the dust of the street, then threw his head back and howled. “Oh, Lord, take me! Spare me from these tormenting phantasms!”

“What’d he just call us?” Scratch asked with a frown.

“I don’t think he’s talking about us,” Bo replied as he swung down from the saddle. He handed his reins to Scratch. “Here. Hang on to my horse while I see what I can do for the old-timer.”

It was rare for the two of them to run into anybody they could call “old-timer.” This man, who appeared to be the sole inhabitant of Duster, fit the bill, though. He looked to be in his seventies, with long, tangled white hair and a ragged beard that reached down to his narrow chest. He was so skinny a good wind would blow him away. Filthy rags flapped around his emaciated form. Bo thought the duds had once been a brown tweed suit and a white shirt. The man wore no shoes or boots; his bare feet were scarred and callused.

His eyes rolled like those of a locoed horse as Bo approached. “Take it easy, old-timer,” Bo said, speaking in a calm, quiet tone as he would have if he’d been trying to settle down such a horse. “Nobody’s going to hurt you. I don’t know what happened here, but my friend and I will help you.”

Still on his knees, the man stared up at Bo and said, “Are you real?”

“Real as can be,” Bo assured him.

“You’re not…not like them?”

“Like who?” Bo didn’t think anybody else was around here, but it wouldn’t hurt to ask.

The man placed his hands over his face, the bony fingers with their knobby knuckles splayed out across his gaunt features. “Them,” he said with a shudder. “The ones who torment me.”

“Who?” Bo asked again, as it suddenly occurred to him that the old man might be talking about some of those renegade Apaches who snuck across the border now and then. Apaches were known for being the most skillful torturers on the face of the earth.

But they weren’t who the old man had in mind. As he lowered his hands he gazed up with the most fear-haunted eyes Bo had ever seen. “Them,” the old man croaked. “The children!”

Then he pitched forward on his face, either in a dead faint—or just plain dead.

With all the debris around, Scratch didn’t have any trouble finding enough scraps of dry wood to start a fire. He built a small one in the shade of a building that was still upright, a two-story structure with a sagging balcony along the front that had probably been a hotel or a saloon. Bo lifted the old man and carefully carried him into that same shade. The old-timer didn’t weigh much at all; his body was like a bundle of twigs inside his leathery hide.

Scratch got some coffee brewing, using water from their canteens. Bo made sure the old man was still alive. He found a threadlike but fairly steady pulse in the hombre’s neck. He checked the man’s body but didn’t find any wounds.

“Looks like he’s about starved to death,” Scratch observed.

“Starved to death…and scared to death on top of it,” Bo said. “We’ll have to get him awake again so he can tell us what happened here.”

“Whatever happened, it’s too late for us to do anything about it. And it ain’t really any of our business, either.”

Bo just looked over at Scratch, who sighed and went on, “Yeah, I should’ve knowed better than to say that, shouldn’t I? You’d reckon after all this time I’d know you can’t abide a mystery, Bo Creel.”

“Let’s just get a little food and coffee in him and see if it helps.”

The old man roused enough to gulp at the coffee when Bo held a tin cup to his lips. He had let the strong black brew cool off some first so the old-timer wouldn’t scald himself. When the man had swallowed some of the coffee, Bo spooned beans into his mouth. The old-timer swallowed without even chewing.

“Whoa there, mister,” Bo said. “Take it easy. I know you’re hungry, but you’re liable to make yourself sick if you keep that up.”

The old man’s rheumy eyes flickered open. “Who…who are you?” he choked out. His voice was hoarse from the screaming he had done earlier.

“My name’s Bo Creel. This is my partner, Scratch Morton.”

Scratch tugged on the brim of his Stetson. “Howdy.”

The old-timer looked back and forth between them. He was still a little wall-eyed. “Wh-what are you doing here?”

“Just passing through,” Bo explained. “This is Duster, isn’t it?”

The man’s head jerked in a nod, bobbing a little on the skinny neck.

“We figured on buying some supplies here,” Bo went on. “We didn’t know that something had happened to the town.”

“A deluge,” the old man muttered. “The rainbow was a promise from God that never again would the world be destroyed in a flood, but that night…that terrible night…I began to doubt the word of the Lord.”

“Came a gully-washer and a toad-strangler, did it?” Scratch asked.

The old-timer shuddered. “The heavens opened, and a torrent came upon the earth. When the ridge gave way, it was like a wall of water came roaring down on the town. An avalanche, only of liquid rather than stone. I saw it coming.” He lifted his hands and covered his face again. They muffled his voice as he went on, “I tried to get the children out of the orphanage, but it was too late. They fled to the upper floor, thinking it would be safer there, but then…then…”

Frowning, Bo and Scratch glanced at each other. Bo leaned closer to the distraught old man and said, “That big brick building on the edge of town…it was an orphanage?”

The man lowered his hands and nodded. “Yes. There were more than thirty children living there.” His voice was hollow with agonizing memories. “I…I was the director. George Ledbetter is my name. The Reverend George Ledbetter, although God has turned His back on me now, and rightfully so.”

“You shouldn’t ought to feel like that,” Scratch said. “Ain’t no way one man can stop a flood.”

“No, but I should have died in there with them,” Ledbetter rasped. “The older children hustled the little ones upstairs, trying to save them, but then…the flood washed out the foundation. The men who built it must not have used the proper materials…oh, dear Lord, the sound as the timbers began to creak and then snap, the rumble as the walls began to collapse…but even over those sounds, even over the terrible noise of wind and water, I could hear the screams from inside.”

The old man began to shake and sob.

Bo let him get some of it out, then said, “You must not have been in the building when the flood hit.”

Ledbetter managed to nod. “I went out to make sure no one had been left outside and then couldn’t get back in. I thought the children would be safe on the second floor, that the water wouldn’t reach that high. I actually thought that I was in more danger than they were, and I did come near to drowning as the water swept me away. I…I had no idea that the building would fall….”

“You couldn’t have known that it would,” Bo told him. “What happened to the rest of the people in town?”

Ledbetter passed a trembling hand over his face. “Many of them were killed. When the waters receded I performed funeral services for what seemed like days on end. The few who survived didn’t want to stay here any longer, and no one could blame them. They left. But I couldn’t. I had to stay.”

“How long ago was that?” Bo asked.

“Six months? Eight?” Ledbetter shook his head. “I don’t really know.”

“And you been here ever since by yourself?” Scratch asked.

“Yes…but I’m not really alone. The children are here too.”

Bo and Scratch looked at each other again, then Bo said, “I thought you said all the children were killed when the orphanage collapsed?”

Ledbetter nodded. “They were. But they are still here nonetheless. They come to me and torment me with their sad eyes and their drowned faces. I see them, pale and lifeless, accusing me with their pathetic gazes. Their spirits will never leave me alone, because I deserted them in their hour of need. They will never know rest, and neither will I.”

“You’re talkin’ about ghosts,” Scratch said.

Ledbetter waved a shaking, bony hand at their devastated surroundings. “What better place for them?” he asked, unknowingly echoing what Bo had said earlier.

Neither of the drifters had an answer for the old man’s question. Bo said, “Drink some more coffee, Reverend, and then have some more of these beans. You need to get your strength back.”

“Thank you, Mr. Creel. This is more than I’ve talked for quite some time. My throat is rather dry.”

Ledbetter slurped down more coffee, and Bo helped him put away a good serving of beans. By then Scratch had fried up the last of their bacon, and the reverend ate some of it ravenously too. Then he leaned his head against the wall of the building and moaned. He closed his eyes and seemed to fall asleep almost immediately.

Bo and Scratch moved off far enough so that their low-voiced conversation wouldn’t be overheard in case Ledbetter was really still awake. “What in tarnation are we gonna do with the old pelican?” Scratch asked.

“We can’t leave him here,” Bo declared. “He’ll starve to death if we do.”

“But he don’t want to go. He could’ve left with the other folks who lived through the flood, if there was anywhere else he wanted to go.”

“That’s only because he feels guilty about what happened to the children in the orphanage.”

“You can sling him on a horse and tote him away from here,” Scratch said, “but that won’t make him feel any less guilty.”

“I know,” Bo admitted. “But I can’t just ride away and leave him here to die, either.” He glanced at the sky. “It’s too late in the day to decide anything. We’ll camp here tonight and try to figure it out in the morning.”

Scratch nodded. “Bueno.”

Ledbetter was still asleep, snoring softly. Bo and Scratch tended to their horses, unsaddling the animals and giving them a good rubdown. The settlement’s public well, at the far end of the street, had water in it and the crank that lowered and raised a bucket still worked, so Scratch filled a trough that hadn’t washed away in the flood and Bo gave the horses a little of the grain they had left.

Taking Ledbetter along with them meant that they would have to stretch their meager provisions even further, but as Scratch had pointed out, jackrabbits were abundant in this part of the country. Surely they would come to a settlement sooner or later.

Dusk didn’t amount to much around here. Once the sun dipped below the western horizon, full darkness came quickly, along with a wind that whipped around the ruined buildings. But during that brief half-light, something stirred inside Bo, a warning prickle that maybe something wasn’t quite right.

He and Scratch hunkered beside the fire, sipping coffee and eating the last of the beans and bacon that Ledbetter had left. Bo set his plate aside and came to his feet. “I think I’m going to take a look around town,” he said.

Scratch glanced up at him. “Something wrong?”

“Probably not,” Bo said with a shake of his head. “I just want to make sure we’re really alone here.”

“Don’t tell me you’re worried about ghosts.”

“Of course not. But we’re close enough to the border that there could be a few Apaches skulking around.”

“Yeah, you’re right.” Scratch reached for his Winchester, which lay on the ground beside him. “Want me to come with you?”

“No, stay here and keep an eye on the horses and the old man,” Bo said. “I’ll be back in a few minutes.”

Taking his rifle with him, he walked along the street. Thick shadows had begun to gather around the wrecked buildings. Movement seen from the corner of his eye caught his attention. He swung his rifle in that direction, then relaxed as he spotted a coyote slinking off into the dusk. Bo chuckled at this uncharacteristic display of nerves on his part. He started walking again and looked in front of him.

Two children stood there.

Bo stopped like he’d been punched in the chest. The kids, a boy and a girl around ten or twelve years old, were about forty feet away from him, standing in front of a building that leaned over at a severe angle. Bo couldn’t see them that well because of the uncertain light. He started toward them and said, “Hey. Hey, you kids—”

They disappeared.

With the thickening shadows it was hard to tell, but it seemed to Bo that the children were there one second and gone the next. But that was impossible, of course. He was too hardheaded to believe in ghosts. He loped forward, looking on both sides of the street for them.

But they were gone.

Bo wasn’t the sort of hombre who cussed very often. If he had been, he would have let out a few choice words right then. Instead he tucked the Winchester under his arm, fished a lucifer out of his pocket, and snapped it into life with his thumbnail. The glare from the match lit up the dirt as Bo lowered the flame toward the street. He was looking for footprints, proof that the two children he’d seen had really been there.

He didn’t find any.

Duster lived up to its name; the dust in the street was thick, and Bo didn’t see how anybody could have walked through it without leaving some sign. He grimaced as the flame reached his fingers. He dropped the match and ground it out with his boot heel.

“You kids come out,” he called softly. “Nobody’s going to hurt you, I promise.”

There was no sound except the soft whistling of the wind that had sprung up.

That was the explanation, he thought. The wind had wiped out any tracks the kids left. Sure, that had to be it. The children were small and wouldn’t leave deep prints in the dust. It wouldn’t take long for a stiff breeze like the one blowing now to blur them beyond recognition.

Bo wasn’t sure if he believed that or not, but it made a lot more sense than thinking those two youngsters were ghosts from the collapsed orphanage.

And yet, Reverend Ledbetter had insisted that the spirits of dead children came to him and tormented him. He seemed to believe it wholeheartedly. Bo had chalked that up to the guilt the old man felt, but what if—

No, he told himself. No what if. There were ghost towns scattered across the West, and Duster certainly qualified. But that didn’t mean they were populated by real ghosts, because there weren’t any such things.

Bo finished looking around the town, and by the time he got back to where he’d left Scratch and Ledbetter, night had settled down completely. “Find anything?” Scratch asked.

“Not a blessed thing,” Bo replied. He didn’t like lying to his partner, but he didn’t want Scratch to think he was losing his mind.

Ledbetter still slept. Bo and Scratch sat beside the fire and talked quietly for a while. The night was quiet except for the wind, which made the flames flicker and dance. Then a rumble sounded in the distance. Bo and Scratch both looked up, and Scratch said, “Thunder?”

“Sounded like it. Might come a little shower up in the mountains. But that doesn’t mean it’s going to flood down here again.”

Scratch looked around as the horses shifted nervously where they were tied with picket ropes to an old hitch rack about twenty feet away. “Somethin’s spooked those cayuses,” he said as he got to his feet with his Winchester. “I’ll take a look.”

“I saw a coyote earlier,” Bo said. “That’s probably what’s got them nervous. They must smell him.”

“Yeah.” Scratch walked toward the animals.

Before he got there he let out a startled yell and flung the rifle to his shoulder. He didn’t fire, though. Bo uncoiled from where he sat on the ground, drawing his Colt as he did so. “What is it?” he asked.

“I…I thought I saw somethin’,” Scratch said. “Over by the horses.”

“That coyote?”

“No.” Scratch hesitated. “It looked like…a couple of kids.”

Scratch’s shout had roused Ledbetter from sleep. The old man heard what Scratch said, and he shrieked, “They’re back! Oh, dear Lord, the children are back!”

There was no point in keeping anything from Scratch now. Bo told him what he’d seen earlier. “Yeah, a boy and a gal,” Scratch agreed. “No more’n twelve years old, either of ’em.”

Ledbetter moaned. “Those are the spirits that always appear to me. The girl’s name is Ruthie. The boy is Caleb. They died when the orphanage collapsed.”

“That don’t hardly seem possible,” Scratch insisted. “Folks don’t just get up and walk around when they’re dead. It ain’t natural.”

“Nothing is natural about this accursed town, my friend.” Ledbetter shuddered. “Nothing.”

A distant flicker of lightning to the north made Bo glance in that direction. Ledbetter noticed it too and whimpered, probably at the memories that sight must arouse. No doubt those were the first warning signs the inhabitants of Duster had had on that night months earlier: the rumble of thunder like the sound of distant drums, and fingers of light clawing their way across the ebony skies.

“God is about to visit His final judgment on Duster,” Ledbetter went on. His voice rose on a note of hysteria. “You should leave, my friends. Leave while you can still save your immortal souls!”

The ragged old preacher leaped to his feet and began dashing back and forth, howling like a madman. Scratch said, “Dadgummit!” and tried to grab him, but Ledbetter was too fast. Scratch missed. Bo moved to get in the old man’s way, but Ledbetter darted past him too—then tried to stop as a dark shape loomed around the corner of the building, blocking his path. Ledbetter bounced off of whatever it was, stumbled, shrieked, and fell to his knees.

This was no apparition, Bo knew. Ledbetter had run into something—or someone—solid. Bo reached for his gun, but the metallic ratcheting of a revolver being cocked made him freeze.

“Hold it, both of you hombres,” a deep, gravelly voice rasped. “Keep your hands away from them hoglegs.”

Several more men came around the building. Starlight glinted on the barrels of the guns they held. Bo couldn’t make out many details about them, but he felt the menacing undercurrent in the air.

“No need to go waving guns around,” Bo said in a calm, level voice. “We’re not looking for any trouble.”

Ledbetter lay huddled on the ground, whimpering. The first gunman jerked his Colt toward the preacher and asked, “What the hell’s wrong with this old coot?”

“He’s just scared,” Scratch said. “There ain’t no need to hurt him.”

“Scared o’ what?”

Ledbetter looked up and sobbed, “The Lord’s vengeance! Save yourselves! Flee while you can!”

One of the other armed men said, “He’s loco, Tarver. You’d be doin’ him a favor if you put a bullet in his head.”

The leader turned sharply toward the man who had just spoken. “You’re the one who’s loco, you damn fool! You know better’n to go spoutin’ my name all over the place.”

“Sorry,” the man muttered.

But the damage was done, and they all knew it—all except Ledbetter, who didn’t seem to know anything except his fear. Sam Tarver was the leader of a gang of outlaws that had been plaguing West Texas for months. Posses hadn’t been able to run him and his men to ground, so now the army was giving it a try. Bo had seen a newspaper article about Tarver in El Paso, before he and Scratch left in a hurry.

Tarver turned toward Bo and Scratch again and came close enough for them to see that he was a big man with a craggy face and several days’ worth of beard. “You fellas got horses,” the boss owlhoot said. “We want ’em.”

“We only have two horses,” Bo pointed out, “and there are…” He made a quick head count. “Five of you.”

“Yeah, well, that’ll still let us rest two of our mounts,” Tarver said. “Anything that helps us move a little faster and stay ahead o’ that cavalry patrol.”

So the army was catching up to the gang, Bo thought. In fact, he seemed to recall reading that Tarver’s gang was larger than five men. He wondered if the outlaws had already fought a skirmish or two and lost some of their members.

“We’ll want any supplies you got too,” Tarver went on. “And hell, you might as well go ahead and hand over any dinero in your pockets. We’ll make it a clean sweep.”

Lightning flashed as he spoke, and a crash of thunder followed his words like punctuation. Reverend Ledbetter howled like a kicked dog and curled up on the ground again.

“Maybe you’re right, Harry,” Tarver added. “Puttin’ a bullet in this crazy varmint’s head would be a blessin’.”

“I thought you said we wasn’t supposed to use each other’s names.”

Tarver shrugged. “Well…it don’t hardly matter now, does it?”

Bo and Scratch both knew what that meant. The outlaws didn’t intend to leave anyone alive in Duster. They didn’t want anybody telling the cavalry patrol which way they had gone. Five to two odds were pretty heavy, especially when the five already had their guns drawn, but the drifters had faced worse in their adventuresome career. And since they still had their guns, they’d be damned if they would die without a fight.

But before Bo and Scratch could hook and draw, one of the outlaws who hadn’t spoken before suddenly said, “Look yonder, Tarver! It’s a couple o’ kids!”

“What?” Tarver exclaimed. “Where?”

“Right over there,” the owlhoot said, pointing. “I…I…Where the hell’d they go?”

“Spirits!” Ledbetter screeched. “Spirits of the dead!”

“Shut up!” Tarver roared. “I’m gettin’ mighty tired o’ you, old man—”

“Hey, mister….”

The childish voice floated through the air and seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere. It caused all of the men except Ledbetter to jump a little and look around, even the usually iron-nerved Bo and Scratch. They had already encountered the mysterious youngsters, and now they heard the boy’s voice.

The girl chimed in a second later, saying, “Over here, mister…” The voices were so wispy they didn’t seem real.

But what else would you expect ghosts to sound like, Bo thought?

“No, over here, over here!” the boy called.

“There!” one of the outlaws cried. He triggered wildly, Colt flame blooming in the darkness as the shots gouted from his gun. He emptied the weapon, and as he lowered it, he said, “Where the hell’d they go? I hit the little bastard, I know I did!”

“Stop shootin’, you idiot!” Tarver said. “That’s a little kid you’re blastin’ away at!”

“No, it’s not,” Bo said, figuring that any distraction would work in his and Scratch’s favor. “That little boy and girl were orphans who were killed in a flood here months ago. The water made the orphanage collapse. More than thirty children died that night, and their spirits are here in Duster.” Bo paused as more lightning glared across the sky. “They’ve come back tonight.”

“Over here…over here…over here…”

The outlaws twisted and turned frantically, looking for something that wasn’t really there. Scratch leaned close to Bo and said, “That one hombre never reloaded his gun.”

“I know,” Bo replied. “That makes it four to two. Good enough odds for you?”

“Damn good enough,” Scratch snapped, and slapped leather.

“Look out!” Tarver yelped. “Get those two saddle tramps!”

The outlaws’ panic had given Bo and Scratch a chance to draw their guns. Both Colts blasted as the two drifters split up, Bo going right and Scratch going left. Bo hoped that Ledbetter would have sense enough to keep his head down.

One of the outlaws spun around with a harsh cry as a bullet from Bo’s gun drilled through his body. Another doubled over as one of Scratch’s slugs punched into his belly.

But then Tarver and the desperado called Harry began to return fire, forcing Scratch to dive behind the old water trough. Bo dashed for the far side of the street, but it was too far away. He would never make it.

Sure enough, a bullet traced a trail of fire across the outside of his left thigh. The wound was minor, but the impact was enough to knock his leg out from under him and send him tumbling to the ground. He knew he would be ventilated good and proper before he could get to his feet again.

But he had landed so that he was turned toward the old hotel or saloon or whatever it was, and in the light of the campfire Bo saw Reverend Ledbetter rise from the ground and throw himself at Sam Tarver. “No!” the preacher screamed. “Vengeance belongs to the Lord—and to the children!”

A pair of shots erupted from Tarver’s gun. Ledbetter crumpled as the bullets smashed into him. His action gave Bo time to draw a bead on Tarver, though, and before the boss outlaw could fire again, the walnut-handled Colt leaped in Bo’s hand. Three shots rolled out, all of them hammering into Tarver’s chest and driving him backward so that he fell heavily on the old boardwalk. The planks were rotten. Tarver busted right through them.

At the same time, Scratch fired from behind the water trough at Harry. One of the slugs smashed the outlaw’s elbow; the second tore his throat out. He went down with blood fountaining from the wound. It looked more black than red in the firelight.

That accounted for four of the five outlaws, but the one who had emptied his gun at a ghost was still on his feet. His gun wasn’t empty anymore, either. He had been desperately thumbing fresh cartridges into the cylinder as the battle went on around him, and now he snapped the weapon closed and lifted it, grinning as he aimed it at Bo.

It was Bo’s gun that was empty now. He couldn’t do anything as the outlaw shouted to Scratch, “Drop your guns, mister, or I’ll blow holes in your pard, I swear I will!”

Bo heard the curses coming from Scratch and called, “Kill the varmint!” He wasn’t surprised, though, when Scratch stood up a moment later and tossed his Remingtons to the ground in front of the water trough.

“All right,” Scratch said. “Now what?”

The outlaw chuckled. “Now I get a fresh horse, and an extra one too. No way those troopers’ll catch me.”

Bo knew the man was about to pull the trigger, but before that could happen, something large and dark plummeted from the old balcony. The outlaw never saw it coming as it crashed into his head, shattering as it knocked him to his knees.

Scratch left his feet in a dive, snatched one of the Remingtons from the ground as he rolled over, and came up firing. He had two shots left in the ivory-handled gun and put both of them into the fifth and final outlaw. The man went over backward, twitched a couple of times, and then lay still as a dark bloodstain spread over the front of his shirt.

Around him were scattered the remains of the old rain barrel that had fallen on him.

Bo lifted his eyes to the balcony, saw the gap in the railing where the barrel had been pushed through it. He saw the two children standing there as well, looking down at the street. He halfway expected them to disappear again, but they didn’t. Instead the boy called, “Reverend Ledbetter! Reverend Ledbetter, get up!”

The preacher wasn’t moving, though. Scratch hurried to Bo’s side, helped him to his feet, and whispered, “Them ghosts are back.”

“They’re not ghosts,” Bo said with a shake of his head. “They’re real, and they just saved our bacon.” He called up to the children, “Ruthie, Caleb, you kids come on down. We won’t hurt you. That’s a promise.”

Another rumble sounded close by. Scratch said, “That ain’t thunder. That’s—”

“Hoofbeats,” Bo said.

Followed a moment later by the sound of a bugle.

The cavalry patrol’s grizzled Irish sergeant took charge of the children while Bo and Scratch explained to Lieutenant Stilwell what had happened here in Duster, both tonight and months earlier, when the flood washed away most of the town.

“I got a chance to talk to those kids a little before you rode in,” Bo said. “They made it out of the orphanage that night before it collapsed, because Ruthie got too scared to stay there and ran out, and Caleb went after her. He’s her brother.”

“Then they were never ghosts?” the lieutenant asked. Scratch grunted like that struck him as sort of a dumb question.

Bo shook his head. “No. They didn’t leave when everybody else did after the flood, because this was the closest thing to a home that they had. And Reverend Ledbetter stayed, so they wanted to be where he was. They tried to take care of him, but his mind was already twisted around. He didn’t believe they were alive. He was convinced they were ghosts.”

“What about the way they disappeared?”

Scratch said, “They been livin’ in this ghost town for months, scroungin’ for food and shelter and tryin’ to take care o’ the reverend whether he wanted ’em to or not, so they know every hidey-hole and shortcut around here. They didn’t know whether to trust Bo and me when we first rode in, so they didn’t come all the way out, just spied on us and eavesdropped until they figured out we wouldn’t hurt ’em. Then Tarver and the rest o’ them owlhoots showed up.”

“And thanks to Ruthie and Caleb taking a hand, we survived that little ruckus,” Bo added. “That’s the story, Lieutenant. It’ll be up to you now to take care of those kids.”

Stilwell nodded. “We’ll take them back to Fort Stockton with us. I’m sure we can find people to care for them.”

The cavalry surgeon who was riding with the patrol had been working on Ledbetter. He looked up from his task and called, “Lieutenant, maybe you’d better get those kids and bring them over here.”

Stilwell nodded, his face grim. “All right, Corporal.” He and Bo and Scratch went over to where Ruthie and Caleb were talking with the massive Sergeant O’Hallihan. Stilwell led the children to the boardwalk where Ledbetter had been placed on a blanket while the surgeon examined his wounds.

Ledbetter’s head was propped up on a folded blanket. He lifted a trembling hand, managed to smile, and said, “Children…Ruthie, Caleb…you’re real?” Although the old man’s eyes were filled with pain, they were clearer now.

“We been tryin’ to tell you that for months, Reverend,” Caleb said. “We just wanted to help you.”

“And in my grief and guilt, I…I would not allow it.” Ledbetter’s lined face contorted. “I’m sorry, so sorry…”

“Don’t worry, Reverend,” Ruthie said. “We know you were just too sad to be thinkin’ straight. We were sad too. All of our friends died. You were all we had left.”

Tears trickled down Ledbetter’s leathery cheeks. The children each took one of his hands and clutched it. “You’ll have new homes now,” he whispered. “Real homes. Thanks to these men…” He looked at Bo and Scratch. “God bless you. My deliverers.”

A long sigh came from him as life faded from his eyes. Ruthie and Caleb started to sob, still holding his hands.

Scratch looked over at Bo and said, “I can’t figure it. We didn’t deliver him nothin’ but a mess o’ trouble.”

“Not to his way of thinking.” Bo looked up at the mountains. The thunder was faint now, and the lightning only a fading glow. “Looks like the storm is moving on.”