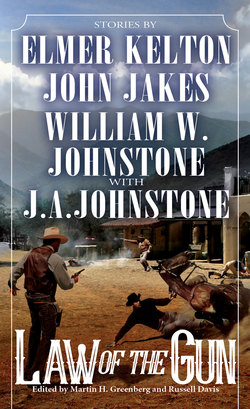

Читать книгу Law of the Gun - Martin H. Greenberg - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Trouble with Dudes Johnny D. Boggs

ОглавлениеThe silver had tarnished, the etchings faded, the chain and fob long gone, and he couldn’t read the sentiment engraved on the inside of the case, which he had to pry open with a fingernail since the release mechanism hadn’t worked in years.

Snapping the cover shut, Lin Garrett wondered why he even kept the pocket watch. It didn’t work. Much like me, he thought.

Oh, he worked. A man had to work to eat, but Garrett didn’t put his heart into it anymore. He worked so he wouldn’t starve or freeze, but a proud man would never find enjoyment in mucking out stalls, swamping saloons, sweeping out stores, or being polite to dudes.

Staring at the broken watch, he sat on an overturned bucket inside the barn, trying to figure out how he had gotten so old, so worthless, so forgotten. Nothing to his name but a silver Aurora watch that had stopped keeping time ages ago. Years earlier, people had called him sir, spoken to him with respect, sometimes admiration, other times fearfully. Now, they hardly spoke to him at all.

Those dudes had, though.

They had driven up in a pair of Ford Model Ns, mud-splattered two-seaters about as basic as a body could find in a big city, but mighty fancy for a ranch in southern Wyoming. When one of those horseless carriages backfired, the noise and the odd sight of the automobiles sent his horse pitching, and Garrett found himself tasting gravel. Which, years ago, wouldn’t have embarrassed him. By grab, he had been dusted so many times he had lost count, had broken both arms, a leg, his collarbone and wrists at least once, and his nose was about as crooked as the road leading to the Aurora Cattle Company & Guest Ranch. Yet the dudes had braked their Fords hard, jumped to the ground, and raced to the corral. They pulled him to his feet, fetched his hat, dusted off his shirt, anxiously asking if he were all right. Even the Aurora foreman had ambled over from the bunkhouse and told Garrett he should call it a day.

The dudes hailed from New York, had come to Wyoming to live the West. They’d called him names like old-timer, hoss, and pard.

“The name’s Garrett,” he told them with irritation.

“I’m Seth Thomas,” said the tallest of the four. “Like the watch company.”

Garrett started to tell Seth-Thomas-Like-The-Watch-Company to go to hell, but he caught the foreman’s hard frown, realized that these dudes were paying customers, and, more important, he needed this job. So he shook each dude’s hand.

“That what brought you to this ranch?” he asked the tall one.

Seth-Thomas-Like-The-Watch-Company stared at him blankly.

“Aurora,” Garrett said lamely. “Like the watch company.”

The kid, maybe in his early twenties, shrugged. “Never heard of it.”

“Before your time,” Garrett said, and had headed for the barn.

The watch had been new when the mayor presented it to him in 1884, among the first solid silver watches produced by the Aurora Watch Company. Back then, Garrett had been a lawman, and the watch was a token of appreciation for valuable service to Flagstaff, Coconino County, and Arizona Territory. Or something like that. He had been written up in territorial newspapers, even in the National Police Gazette. Street & Smith had published a couple of dime novels that were supposedly based on his life. Or something like that. Garrett had never read the damned things. The Aurora Watch Company had failed in 1892, though, and around that time Garrett had pretty much become a failure himself. He couldn’t understand what had happened to him, other than he had just gotten old.

The barn door’s hinges squeaked, and Garrett slid the watch into his vest pocket. He pushed himself off the bucket, joints popping, hip and shoulder stiffening, as lanky foreman Sam Cahill, about twenty years younger than Garrett, approached him.

The foreman spit out a mouthful of tobacco juice, then hooked his thumb toward the door.

“You made an impression on ’em dudes,” he said.

“I been bucked off before. Ain’t the first time. Won’t be the last. Didn’t hurt me none.” He relaxed, forcing a smile. “Just my pride.”

“Uh-huh. Leader of the group’s Jason C. Hughes, nephew of Charles Evans Hughes. That’s the Charles Evans Hughes.”

Garrett said nothing. Charles Evans Hughes meant as much to him as the Aurora Watch Company meant to young Seth Thomas.

“Charles Hughes, the governor of New York, the gent William Taft offered the vice presidential nomination to, only Hughes turned him down. Those kids all just graduated from Brown University. Plan on enterin’ Columbia Law School, but first, they want to see the elephant.” He spit again. “They been readin’ Wister’s book.”

“Seems like everybody has.”

“Uh-huh. ‘When you call me that, smile.’ All that nonsense. One of those dudes asked me if I had knowed Trampas. Guess I’ll never understand book-readers.”

Garrett waited.

“Well, Wister spent some time on a ranch like this one. So did Teddy Roosevelt, or so I hear tell. So Jason C. Hughes has come here to shoot an elk, work cattle, chase mustangs, play cowpuncher with his friends. They’ve come to see the West, least the West they read about thanks to Mr. Wister.” Sam Cahill sighed. “Never thought I’d be nurse-maidin’ dudes, but it’s a new century, Garrett, and beef prices ain’t what they used to be.”

Garrett nodded just to do something. There wasn’t anything to say.

“They want you to take ’em.”

He had something to say to that. “What for? You got two hands to ride herd on your guests. You hired me—”

“I hired you so you’d have something to eat, Garrett. I put those boots on you ’cause what you had when I found you at the depot had more holes than leather. I put that jacket on you, and I hired you to take orders. Those dudes think you’re a bona fide Western man, a by-God Owen Wister hero, and I allow you look the part, or once did. They want you to show ’em the West.”

The foreman shifted his chaw to the other cheek, then shook his head. “Look, Garrett, I didn’t mean to speak sharp to you, but you see the fix I’m in. The kid asked for you, and he’s a top-payin’ customer from a mighty important family back east. At least three of our board of directors live in New York, so these are important guests.”

Board of directors! When Garrett had ridden for various brands back in his prime, before he had become a lawman, ranches were run by ranchers, not boards.

“Way I figure it,” the foreman kept saying, “you could take ’em down by Muddy Creek, show ’em some country, maybe find a bull elk or some muley, and check the herd down that way—my line rider quit two weeks back—let ’em push a few dogies, then bring ’em back here and we’ll send ’em back to the U.P. depot with their ear-splittin’, putrefyin’ horseless carriages. Give you some time in the open country. Got to beat muckin’ stalls. Do a good job, maybe I’ll let you be my line rider down yonder.”

With a final spit, the foreman held out his hand.

Sighing, Garrett clasped the extended hand, knowing he should have quit, knowing he was making a mistake.

He just didn’t know how big.

Jason C. Hughes, Seth-Thomas-Like-The-Watch-Company, and the two other dudes—one named Todd and the other Abraham, although Garrett couldn’t remember which was which—were advertising a leather shop in their chaps, brand-spanking-new boots, dressed like they had stepped off the cover of one of those dime novels. Sam and the wrangler had put the boys on the gentlest horses the Aurora had, and then sent Garrett, pulling a pack mule, toward Muddy Creek.

“Bring ’em back in a week,” Sam Cahill had instructed him, and with a wink added, “and try to bring ’em back alive.”

He kept the pace easy, pointing out a golden eagle, some curious coyotes, and letting the dudes chase after a handful of mustangs. At dusk, he watered and grained the livestock, boiled the coffee and fried the bacon, and even scrubbed the dishes while Abraham, or maybe it was Todd, fetched a flask from his saddlebags, and the dudes started drinking.

“Ever seen anything like this?” Jason C. Hughes asked.

“I’d be obliged,” Garrett said, “if you wouldn’t point that rifle in my direction.”

Hughes laughed. “It ain’t loaded.” He swung the barrel toward Seth Thomas and pulled the trigger. It clicked loudly. “You’re dead, Seth,” he said, and all the boys laughed.

He held the rifle up to show Garrett, worked the bolt, and laughed. “It’s brand-spanking new, old man. A Mauser, and I got the scope sighted in, so I’ll be able to drop an elk from more than a thousand yards. Dumb animal’ll never know what killed it.”

“That’s mighty sporting of you,” Garrett said.

“What’s that on your hip, Garrett?”

“An old Colt.”

“Old?” Todd or Abraham sniggered, pulling one of those newfangled hammerless automatic pistols from a holster. “That’s an understatement. This is what a Colt looks like now.”

“You learn that from The Virginian?” Garrett said. “Thought you boys wanted to live the West. We don’t carry toys like that in this country.”

That seemed to shut them up, and he poured a cup of coffee for himself, wishing he had thought to have brought along a flask. Six more days, he thought.

By the third day, he had had enough.

When Jason C. Hughes aimed the Mauser at the pack mule, Garrett charged across the camp, jerked the rifle from the New Yorker’s grasp, and heaved it into the arroyo. He wanted to scream at the kid, to tell him he had warned him about pointing it, that all weapons should be considered loaded, and that he wouldn’t tolerate this foolishness anymore. Yet all he could do was put both hands on his knees and try to catch his breath. The effort pained him more than getting dusted by a horse.

“You crazy old man!” Jason C. Hughes leaped to his feet, scrambling into the arroyo, kicking up red dust. “Do you know how much money that Mauser cost my father?”

As he filled his lungs, a shadow crossed over him. “Better watch yourself, old-timer,” a voice told him. “We don’t want you to keel over from a heart attack.”

Garrett instantly straightened, and smashed Todd’s nose. Or maybe it was Abraham’s.

A second later, the gunshot ripped through the camp, echoing across the countryside, and Garrett lay on his back, spread-eagled, thinking how this was a bitter end to sixty-five years. Killed by a bunch of greenhorns in the middle of nowhere for a miserable job that paid him thirty a month and found, the same wages he had drawn forty years earlier, only back then he had worked with and for men he had liked.

“Criminy, Abraham, put that thing away!”

“Hey, what’s all that shooting?”

“Abraham has killed the old fart! Fool almost broke my nose!”

The mule screamed, and hoofs stomped. More voices, but Garrett couldn’t understand the words.

Seth Thomas knelt over him, his face ashen, lips trembling.

Garrett flexed the fingers on his right hand, blinked, moved the hand and placed it on his chest. He felt blood leaking down his side, then slid a finger into the vest pocket, pulling out the shattered remains of the Aurora watch. Slowly, he sat up.

“He isn’t dead!” one of the dudes screamed in a nasal voice.

Garrett looked across the camp. Abraham sat on his bedroll, mouth open in surprise, the Colt automatic on the ground beside his boots. Todd stood over his friend, holding a rag against his bloody nose. Well, now he could tell those two apart. Jason C. Hughes had climbed out of the arroyo and wiped the dust off the Mauser with a handkerchief, more concerned about his rifle than Garrett’s health.

“You all right?” Seth Thomas asked.

He nodded. The .25-caliber slug had smashed the watch, then cut a nick across a rib before it spent off somewhere. The wound wasn’t much, although he’d have a hell of a bruise come morning. He smelled whiskey, realized Seth Thomas had unscrewed a flask and was offering him a drink, which Garrett accepted.

After pulling himself to his feet, he forced himself to walk over to Todd and Abraham, and just stood there, right hand on the butt of his old Colt. He kicked the automatic pistol into a clump of cheap grass. “Last person who shot at me got killed,” Garrett said.

Abraham swallowed. “It just went off. I didn’t mean—”

“That’s why I warned y’all about not pointing them things.”

“Old man,” Jason C. Hughes said, “you attacked Todd. Abraham was protecting our friend. Thought you had gone crazy.”

What he wanted to do was draw his .44, but he kept thinking about Sam Cahill, and kept remembering how cold winter got in Wyoming, how the bunkhouse stayed pretty warm, and that he needed a job. Criminy, it was an accident. The dude didn’t mean to shoot him, had just been scared. Let it go. Give you something to laugh about during the long winter. Then Seth Thomas’s voice sounded.

“My lord…you’re Lin Garrett, the famous Arizona lawman.”

He fingered the circular piece of tarnished silver, now punctured by a .25-caliber bullet, and could barely make out his name. He could see far just fine, but close-up, well, that was another story.

To Marshal Lin Garrett

From the People of Flagstaff, A.T.

The bullet had obliterated the rest, and Garrett tossed the remains of his watch case into the fire.

“My grandfather told me stories about the famous Lin Garrett,” Seth Thomas was saying. “Grandfather came from Boston bound for Arizona with…oh, I can’t remember the name.”

“The Arizona Colonization Company.”

“That’s it!”

“You never told me your grandfather was a Westerner,” Jason C. Hughes commented.

“Oh, Grandfather didn’t stick it out.” Seth Thomas shrugged. “He returned to Boston after a couple of years.”

“What was your grandpa’s name?” Garrett asked.

The dude told him, but Garrett shook his head. He couldn’t remember names anymore, especially names from thirty years back.

“I’ve heard of a Pat Garrett,” Todd said, just to say something. His nose had stopped bleeding.

“He got killed a short while back,” Jason C. Hughes said. “Read about it in the newspapers.”

“No kin,” Garrett said.

“Grandfather showed me a book that had been written about you,” Seth Thomas said. “One of those penny dreadfuls. He read parts of it to me, but I can’t remember much about it.”

“Nothing to remember,” Garrett said. “Just lies.”

“So you used to be famous, eh?” Jason C. Hughes laughed. “Maybe Owen Wister should write a book about you. And to think, Abraham almost killed you. That would have been something.”

“You aren’t going to tell Mr. Cahill, are you?” Abraham asked.

“No harm done,” Garrett answered, warmed now by Seth Thomas’s bourbon.

“Well, I haven’t killed my elk or deer yet, old-timer,” Jason C. Hughes said, “and I want to round up some longhorns!”

Garrett returned the flask to Seth Thomas. “We can check cattle in the morning, but they’ll be Herefords. Longhorns are a thing of the past in these parts. You can try out your cannon on the way back to the ranch. We’ll hunt up some elk in the hills.” He stared at Abraham. “Don’t forget your pistol. And don’t ever pull it on me again.”

He swung off his horse without a word, trying not to flinch from the pain caused by Abraham’s bullet, and fingered the closest track. The dudes slowly reined in, although Todd’s sorrel came close to plowing over Garrett as he studied the sign.

“What is it?” one of the dudes said.

“Elk?” asked Jason C. Hughes.

Polled Herefords, branded with the Triangle A, grazed nearby. Garrett rose, holding the reins to his bay, and walked a few rods farther, not answering the guests, and studied more tracks.

“Those are horse prints,” Seth Thomas said.

Still Garrett kept quiet, found a mound of horse apples, and broke one open, feeling it with the tips of his fingers.

“I hope you plan on washing your hands before you fix our supper, old-timer,” Jason C. Hughes sang out, and his pals laughed.

After he wiped his fingers on his chaps, Garrett mounted the bay, turned in the saddle and spoke with a purpose. “Tracks head toward those hills.” His chin jutted in that direction. “We’re following them.”

“There are plenty of cows here.” Stretching his aching legs, Jason C. Hughes pointed at the Herefords. “Why don’t we just work them?”

“I ain’t interested in those cattle.”

His boots scattered the ash from the fire in the small box canyon.

“When are we going to eat?” Todd asked.

“We ain’t.” Garrett muttered a curse as he looked at the four boys riding with him. One was off in the bushes answering nature’s call, two others looked just too tuckered out to even climb down from their horses, and the fourth, Jason C. Hughes, filled his stomach with whiskey.

“What is it?” Seth Thomas asked.

Garrett climbed into the saddle. “Four riders,” he said, “came into the pasture down there and gathered what I reckon to be twenty head of Triangle A beef. Most likely, they used a running iron on them here, and are herding them toward the state line.”

Hughes corked his canteen, keenly interested. “You mean…rustlers?”

“Looks like.”

“You’re joshing us!” exclaimed Todd.

I wish to hell I were, he thought, but shook his head.

“Should we ride back, tell Mr. Cahill?” Seth Thomas asked.

“Hell, no!” It was Jason C. Hughes who answered. “We go after them, right, old man? Kill some rustlers, now that’s something nobody will believe back in Manhattan. This is just crackerjack!”

“We need help,” Seth Thomas pleaded.

Hughes patted the stock of his Mauser. “We have all the help we need, right?” He pointed at the coiled lariat on Garrett’s saddle. “Just like The Virginian!”

He could put his heart into this. Do a good job, Sam Cahill had told him, and Garrett planned on doing just that. Tracking rustlers filled his bill, even if the posse riding behind him wasn’t up to snuff. Well, thirty years ago, he had ridden with posses about as worthless. Besides, at least Jason C. Hughes and Seth Thomas showed some interest in learning what it took to be a lawman.

“When do you think we’ll catch them?” Todd asked.

Garrett shrugged. He had maintained a hard pace, but had slowed to a walk, as much for the sake of the dudes as the horses. Todd and Hughes had ridden up alongside him, and he cast a quick glance over his shoulder to see how far the other two had fallen back. Swearing softly, he drew rein to let Seth Thomas and Abraham catch up. The bay took the opportunity to graze, and Garrett leaned over and patted the gelding’s neck.

“Then what?” Todd asked.

“Depends on the rustlers.”

“Be like Steve in The Virginian, eh?” Jason C. Hughes grinned. “String ’em up.”

He was glad Abraham had caught up and asked, “Do we rest now?” Because Garrett did not like Jason C. Hughes’s question.

“No,” he told Abraham, and kicked the bay into a trot.

You got an old man’s memories. He coaxed his horse into an arroyo, leaning back in the saddle, wondering if those dudes would be able to make the climb down, but not really caring. String ’em up. Something the greenhorn had read in a damned book. Smiling when he had said it.

As a lawman, he had arrested plenty of rustlers, but couldn’t remember anything about them, yet could never forget what had happened in Colorado when he had cowboyed. Those had been horse thieves, and they had hanged. He had helped string ’em up. Memories. Sometimes he hated them.

Thunderheads rolled over the mountains to the east. Garrett hobbled the bay, drew his carbine from the scabbard, and held a finger to his lips.

He pointed to Todd. “You stay with the horses. Keep them quiet. Rest of you, follow me.”

Ignoring the stiffness in his legs, he moved up the hill and into the brush, smelling wood smoke, coffee, maybe even beefsteak. Near the crest, he dropped to his stomach and crawled the final few rods until he could look down at the line shack.

“I don’t see any cattle,” Seth Thomas said softly.

“No.” But on the far side of the log cabin he could make out a black birch farm wagon, worn but useable, and five horses in a rawhide-looking corral behind the line shack, buttressed against sandstone formations that jutted out of the floor like tombstones. Smoke snaked from the cabin’s stovepipe.

“How many times can that Mauser of yours shoot?” Garrett asked.

Jason C. Hughes withdrew a five-shell clip from his jacket pocket. “As fast as I can work the bolt,” he said with a grin. “I have plenty of ammunition.”

“All right,” Garrett said, “here’s the way we play this hand.” He handed his Winchester to Seth Thomas. “You head down to the corral, keep upwind of the horses. Hughes, you stay put right here where you got a clear shot at the door. Abraham, you come with me. Stay behind that rock yonder. I’ll get to the well, then holler for them to surrender.”

“And if they don’t?” Jason C. Hughes asked.

“They’d better. None of y’all pull a trigger till I fire a round. Then just shoot over that line shack four or five times apiece, fast as you can. I want them to think I got an army of deputies out here.”

“Hot damn!” Hughes shouted. “This is a hell of a lot better than shooting some elk!”

Garrett glared at him, and Hughes shrugged.

“Sorry, old man,” he whispered. “You best hurry.”

He had carried the Colt since the War of the Rebellion, an old cap-and-ball .44 that he had eventually converted to take brass cartridges. When he reached the well, he pulled the revolver, blew on the cylinder, eased back the hammer, and looked around him. Abraham crouched behind the rocks, Colt automatic in a sweaty hand. Seth Thomas knelt behind the corner post of the corral, the .30-30 aimed at the shack’s roof. Up on the hill, sunlight reflected off Jason C. Hughes’s Mauser, and Garrett smiled.

This might work, he thought, and won’t there be some stories told at the bunkhouse this winter. Lin Garrett brings in a band of rustlers with nothing but a bunch of dudes riding for him. He fired a round into the air, then yelled, “I’m a federal marshal, and I got a posse surrounding you!” With a nod, he listened to the gunfire, keeping his eyes on Abraham, making sure the fool kid didn’t accidentally shoot him again, and when the echoes died down, as Abraham slid another clip into the Colt, Garrett thought about the lie he had just told. Well, he had been a federal deputy some years back, and he did have something of a posse.

“Come out with your hands up!” he yelled at the cabin door. “Else we’ll gun you sons of bitches down or burn you to a crisp!”

The door swung open, a mustached young man stepped out, waving a faded bandanna, saying, “Don’t shoot no more!”

Immediately, Jason C. Hughes dropped him with a bullet through his leg.

“Damn it!” Garrett climbed to his feet, not even thinking that those other three rustlers might gun him down, yelling at Hughes. The horses loped around the corral, close to the poles, spilling Seth Thomas from his seat, and Abraham muttered something that sounded like a laugh.

“Hold your fire! And the rest of you sons of bitches come out of that shack before we torch the damned thing!”

Inside the cabin, a baby cried.

“Aw,” Garrett said, “hell.”

“Listen, mister,” the man with the mustache said through clenched teeth, “I got a sick wife and a baby. Nothin’ to eat hardly. It ain’t like you think.”

Garrett drew a silk bandanna through the bullet hole in the meaty part of the man’s thigh, then splashed whiskey over the wound. The man screamed and almost fell out of the chair.

“This is Triangle A land,” Garrett told him. “You’re squatting.”

“I know that, but my wife took sick. Wasn’t nobody here. Been tryin’ to get to Lander. Matilda, that’s my missus yonder, she’s got a sister up there.”

Garrett looked at the woman, feverish, lying on a cot, saw Seth Thomas bouncing the baby girl on his knee, and ran the man’s story through his head once again.

Three riders stopped for the night, each with an extra horse, suggested he help them round up some cattle, said they’d pay him five dollars. He didn’t know the stock was stolen, just thought he was helping out.

That part was a lie. They’d taken the cattle to a box canyon, worked the brands with running irons. No, this gent knew they were rustlers. But…well…Garrett had thrown a wide loop in his younger days, too. Lots of cowmen had.

Once they had driven the cattle back here, the wounded man had said, the three strangers had left the winded horses in the corral, saddled fresh mounts, and ridden out with the cattle. Tracks Garrett had found told him that much was probably true. The three horses left behind were most likely stolen.

“You didn’t suspicion them when they left their horses behind?” he asked.

The man grimaced. “Mister…” was all he could say, sweating heavily.

“You left your wife, sick as she was, and kid here?” Garrett asked him again.

“Matilda insisted on it. Said she was feelin’ better. Wouldn’t be gone more’n a couple of days, and five dollars is a lot of money to me.” He bit his lip against the pain. “When I got back, Matilda had taken another bad turn. You gotta believe me, mister!”

“You butchered one of those steers.”

“They let me. Give me a steer instead of money. Wife’s sick. My girl’s only eighteen months old. You tell me you’d let your family starve. I’ll work off whatever I owe for the beef. And for the week I been at your cabin.”

“You’ll work it off, mister,” Jason C. Hughes said from the doorway. “With a rope.”

The man’s eyes widened. “Look, I got a wife, a daughter, you can’t—”

“Where’d your pards go?” Garrett asked him.

“They wasn’t my pards. Just strangers.”

“Their names?”

“I don’t know. One called hisself Red. There was a tall one, about your size, went by the name of Ed. The other fellow was a Mexican. He never said much. Never heard his name that I recollect.”

“Where’d they go?” Garrett asked again.

“Think they said Virginia Dale. They’re in Colorado by now.”

“Todd and me have the rope ready, old man,” Jason C. Hughes said. “Let’s string him up.”

“Shut up,” Garrett snapped. He started to stand, saw the rustler’s eyes flash in warning, and Garrett reached for his Colt, turning, knowing he was too late, catching the blur of Mauser’s stock as it slammed into his head.

A blacksmith pounded iron against an anvil inside his head, but Garrett forced his eyes open, tried to reach up and test the walnut-sized knot above his temple, felt the hemp rope tight against his wrists, and saw Seth-Thomas-Like-The-Watch-Company sitting in front of him, Garrett’s own .44 pointed in his direction.

Beside him, the baby girl played with Garrett’s spurs, spinning the rowel, laughing when the bobs jingled. The mother slept fitfully.

“Where are the others?” Just speaking caused Garrett’s head to ache.

Seth Thomas glanced nervously toward the open door. “Todd and Abraham do whatever Jason says.”

“Looks like you do, too.”

The dude shook his head. “I…I didn’t. Jason says it’s law, the law of the West.”

“It’s murder.”

“He stole your cattle.”

“You won’t get away.”

Seth Thomas sighed. “I can’t go against Jason, Marshal Garrett. His uncle is…well. And the man’s guilty. You know that.” Trying to convince himself of it, he swallowed. “Just like The Virginian.”

“It ain’t nothing like that, boy. Them’s words. This is real.”

Outside, he heard laughter. Inside, the spurs chimed. Garrett nodded at the baby.

“Y’all going to hang her, too? And her ma?”

“No. I wouldn’t let…uh…. Jason’s a little…crazy. This is…well…the law…Western law.”

“We strung up horse thieves when I wasn’t that much older than you,” Garrett said. “Biggest mistake I ever made in my life, and I’ve made a passel. You think about it.” He closed his eyes.

When his eyes opened, he saw Seth Thomas squatting in front of him, pistol on the floor, opening the blade to a folding knife, and Garrett decided not all dudes were so damned worthless.

“Mister,” Jason C. Hughes said with a drunken laugh, “get ready to be jerked to Jesus!”

Colt in his right hand, Garrett stood in the doorway, taking in the sight of the three dudes, drunk on whiskey, maybe drunker on power, the wounded rustler standing on a flour keg, a rope over his neck, looped around the branch of an ancient cottonwood.

And they saw him.

Garrett felt young, invincible, the way he had felt years ago, back when his life had a purpose. Abraham’s hand darted for the automatic in its holster, and Garrett shot him. Todd had already turned and was running, and Garrett’s second shot kicked up dust between his legs. The dude stumbled into the dust, crying, “Don’t shoot me! For God’s sake, don’t kill me!”

Jason C. Hughes had grabbed his Mauser, working the bolt, cursing angrily. Garrett’s third and fourth shots splintered the stock, and the heavy rifle dropped to the dirt. So did Jason C. Hughes, shaking his hands, groaning, then freezing as Garrett steadily drew a bead on the dude’s forehead.

Garrett climbed out of the wagon, and turned back to face the woman and her baby, and her husband, resting inside the wagon. “Nearest town’s Saratoga,” he said. “Closer than Triangle A headquarters. Got some mineral baths there, and a doctor. Get you fixed up in no time.” He looked behind him at Todd and Abraham, hands tied to the horns of their saddles, as tight as Garrett could manage, a stripped bed linen wrapped around the bullet hole in Abraham’s side. “Got a jail, too.”

“God bless you, Marshal,” the woman said weakly.

“I ain’t no marshal, ma’am. Not anymore.” What I am, he thought, is a damned fool.

Smiling, he walked around the wagon and looked up at the driver. “You sure you can handle a team, Seth Thomas?”

“I’ll try,” the boy replied, and glanced uncomfortably at the flour keg and lynching rope.

“Get moving.” Garrett went to his horse, gathered the reins, and swung into the saddle. He turned the bay and nodded at Abraham and Todd. “You boys follow the wagon. Try something foolish, I’ll shoot you dead, or leave you like I’m leaving Jason C. Hughes.”

“Old man!” Jason C. Hughes yelled. “You…I…my father…my uncle…we’ll kill you. You cut me down!”

He nodded again, and the two dudes nudged their horses and followed the wagon up the trail. Garrett nudged his horse closer to Jason C. Hughes, perched precariously on the flour keg, the makeshift noose chafing his throat, his face flushed.

“You can’t leave me here!” the dude said.

How he would love to leave Jason C. Hughes hanging, but, no, he’d just give the boy a scare, ride over the hills, let him sweat for ten minutes, maybe longer. If I don’t forget about him, Garrett told himself. My memory ain’t what it used to be.

“Don’t rock that barrel too much, boy. You’ll wind up like Steve in Mr. Wister’s book you’ve been so jo-fired about. That’s what you wanted to see, ain’t it? Well, you’re about to get a real close look at someone getting strung up.”

Clucking at his horse, Garrett trotted the bay after the wagon and his two prisoners, smiling, enjoying himself.

“Old man! Damn it, you get back here and cut me loose. Cut me down. Damn you, you better do as I say!”

Reining up, Garrett looked over his shoulder at Jason C. Hughes.

“Get back here, and cut me down!” the dude screamed. “Or you’ll rue the day, old man!”

Garrett pushed back the brim of his hat. “When you call me that,” he said, “smile.”

Then he loped away.