Читать книгу The Terror - Edgar Wallace, Martin Edwards - Страница 5

INTRODUCTION

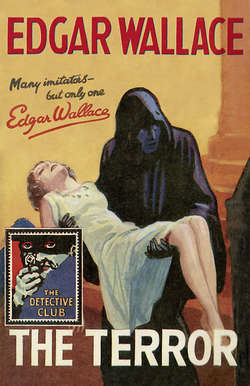

ОглавлениеIN July 1929, Edgar Wallace’s The Terror headed the list of the first half dozen titles published by Collins in their Detective Story Club, the only one which was not a reissue. This lively, melodramatic thriller does not outstay its welcome—its brevity is such that some bibliographies describe it as a short story, although in fact it is a novella with an unusual history. On its first appearance, The Terror was published on its own, its modest length bulked out to 192 pages thanks to the cunning use of a conspicuously large type-face. Rather than resort to the same tactic to achieve its page count, this reissued edition includes the bonus of a second Wallace book published in the following year, and White Face is rather more than twice as long as The Terror.

An enthusiastic preface to the Detective Story Club edition hailed The Terror as ‘a masterpiece of its kind’, and, nearly ninety years later, there is no denying that it displays the characteristics that made Edgar Wallace a literary phenomenon. Margaret Lane, his first major biographer, summarised the lurid plot ingredients: ‘an old mysterious house built over hidden dungeons…hidden treasure…the hooded figure appearing on moonlit nights and leaving a trail of murder in its wake, the shrieking heroine trapped in the dungeon with a sinister madman’. Add to that both a master criminal and ace detective masquerading as someone else, and you have a classic slice of Twenties popular culture.

Just like the early whodunits of Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers, The Terror belongs to an age when people craved escapism at least as much as they had ever done. Memories of the First World War, which in one way or another touched almost every family in the land, were still raw. Edgar Wallace’s thrillers met a particular need, and met it better than any of his peers. He was, G. K. Chesterton said, ‘a huge furnace and factory of fiction’, and the popularity of his books made him a fortune, which he spent as quickly as he earned it.

An intriguing facet of The Terror is the story’s genesis in the theatre. The idea for the story came during the course of an extravagant holiday in Caux in late 1926. Wallace met Bertie Meyer, a theatrical manager, who suggested that Wallace write a play for two prominent actors, Mary Glynne and Dennis Nielsen-Terry. It took Wallace a mere ‘five nervous and preoccupied days’, as Margaret Lane perhaps euphemistically described them, to rise to the challenge. Even more impressive was the result of his frantic labours: the play ran for almost seven months at the Lyceum, and having cost just £1,000 to stage, made £35,000 in profits.

Success in the theatre led to The Terror being filmed; it became Warner Brothers’ second ‘all-talking picture’ before Wallace produced this book version. A more notable screen adaptation came in 1938; the cast included such luminaries as Alastair Sim, in characteristic scene-stealing form as Soapy Marks, and Bernard Lee, best remembered today as ‘M’ in Dr No and ten subsequent James Bond films, as Freddy Fane.

White Face appears to be the only other example of an original book that Wallace based on an earlier stage play, Persons Unknown, although his productivity was so astonishing that his bibiliography is as convoluted as a thriller plot, and it is hard to be sure about such things: The British Bibliography of Edgar Wallace by W. O. G. Lofts and Derek Adley is a full-length work, yet even its industrious authors admitted that, after four years’ research, they were far from confident they had traced all his stories published in Britain, let alone anywhere else. In 1932, White Face was turned into a film, but like the original film version of The Terror, it is now considered officially to be lost, unless any prints turn up in archives or the hands of private collectors.

This tale of a white-masked villain who terrorises London boasts a neat ‘least likely person’ twist, and also some snappy snatches of dialogue, as when a detective opines: ‘Policemen and reporters get their living out of other people’s misfortunes.’ Another police officer expresses the view: ‘The jury is a body or institution which gives everybody the benefit of the doubt except the police.’ A later passage, which has something of a timeless quality, notes: ‘Parliament had been playing too interfering a part in the police force lately…The Home Office had issued new instructions which, if they were faithfully carried out, would prevent the police from asking vital questions. Every step that the crank and the busybody could devise to interfere with the administration of justice had assumed official shape.’

Wallace never pretended to be a literary stylist, but the energy of his writing and the slickness of his plot twists earned him countless readers. At one time, his publishers claimed that he was responsible for one in every four British novels read. If this was an exaggeration, it did at least have the merit of seeming plausible. A Detective Story Club advertisement for The Terror said the tale proved once again ‘that there are many imitators, but only one Edgar Wallace’. This was perfectly true. Richard Horatio Edgar Wallace (1875–1932) was extraordinary among authors in that his life was as extraordinary as his books. He was one of a kind, and the latest biography, written by Neil Clark and published in 2014, is called fittingly Stranger than Fiction.

Wallace’s work had a universal appeal. As Clark says, ‘Among his millions of fans were King George V…Stanley Baldwin, a president of the United States, and a certain Adolf Hitler.’ Writing in 1969, Penelope Wallace, his daughter, suggested that an underlying reason for his popularity was ‘his lack of bitterness’:

‘There are occasions when he is angry, particularly on such subjects as “baby farming” but none where hatred…obscures the text. His villains are usually English and on the rare occasions when they are not home-grown they are imported impartially…There is no trace of racial or religious prejudice and it is rare for the villain to be completely bad. Those who say that his characters are either black or white can never have read his books. Few of his bad men are disallowed a redeeming feature or two.’

Reading tastes fluctuate as time passes, and the world has changed a great deal since Wallace adapted The Terror and White Face from his plays. Fortunately, good story-telling never goes completely out of fashion. Edgar Wallace was a gifted story-teller, and it is a pleasure to introduce these two lively tales to a new generation of readers.

MARTIN EDWARDS

May 2015

www.martinedwardsbooks.com