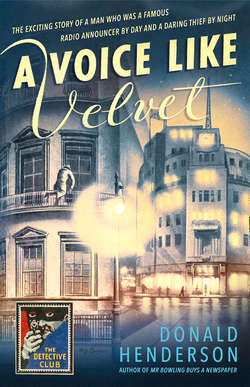

Читать книгу A Voice Like Velvet - Martin Edwards, Donald Henderson - Страница 9

CHAPTER I

ОглавлениеMR ERNEST BISHAM kept as still as possible behind the green velvet curtains and listened to a clock ticking. Suddenly he slipped from behind the curtains and made for the door. He went unchallenged along a corridor and opened the first door he came to. Nobody was in it, it was a bedroom. He went to a window and softly opened it. A few minutes later he was hurrying along a side street and panting slightly. He was not so young as he had been, and he was not so slim as hitherto.

He couldn’t find a taxi, so he got a bus and reached Waterloo Station a little before eleven. Comfortably, he caught the eleven-five for Woking and sat in a first-class carriage, lighting a cigar, and knowing: ‘That porter recognized me again—he knows I’m Ernest Bisham, the Announcer!’ He still got a kick out of it, in spite of much recent mental research. Then he sat back and relaxed, thinking: ‘I promised myself I would never do it again. But I’ve failed myself again. It’s worse than smoking.’ He made a new promise to himself not to do it again, he really would get caught one day, and think of his position now! But he recognized that it meant giving up the biggest thrill of his life, not excluding that first time he had sat at the microphone and read: ‘And this is Ernest Bisham reading it.’ Deep in his overcoat pocket his fingers touched something hard.

Mr Bisham had recently arrived at one of those stages any intellectual man can arrive at during middle life, if he is honest: which stage was to take a day off and have a serious look at himself. So he spent a rather windy March day looking at himself, and in the evening asked Mrs Bisham to have a look at him too. Unfortunately, the evening was interrupted by the arrival of Mr Bisham’s sister. Bess Bisham had the knack of interrupting things. She always brought a bit of an atmosphere with her and somehow or other induced a pause. Even before her brother had become the famous announcer, Bess had possessed a tremendous sort of family consciousness and now it seemed ideal for her to go about saying her brother was, ‘the BBC announcer, you know’. But she was a good sort, and she made a good friend if anyone took the trouble to be patient with her and not laugh at her war efforts.

Mrs Bisham went in for a good deal of sewing in wartime, and she strained her eyes and her pink lips at it, looking genial and concentrative at the same time, with three little lines over the bridge of her large nose. She had a beautiful petal-like skin, it was really the skin of a young girl. Yet she was on the hefty side, in an elegant kind of way. She was called Marjorie, with a j, not a g, and she spent her time saying she must not get snobbish, in spite of the rather snobbish district, and in spite of the determination of the public that announcers must become, and remain, the very hallmark of English respectability. This was all very fine, in its way, but the public might surely be entitled to like its announcers human, in addition? They were human beings, weren’t they? And she had quite a dread of Ernest becoming pompous and inhuman. He was already a borderline case. But both Marjorie and Bess knew that the Bisham family had ‘arrived’ when Ernest came home one night a year or two before and said, as he threw his hat on the hall table: ‘Thank God—they’re transferring me from the Overseas Service! I’m going to be at Broadcasting House! You’ll hear my name on the air!’ As a matter of fact, it was the day Rommel had used up all his best cards and the war, for us, seemed suddenly to have reached a happier turning point.