Читать книгу Assignment Russia - Marvin Kalb - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3 BROADCASTING’S ONE THING, WRITING’S ANOTHER

ОглавлениеThe following day I got an unexpected call from another relative newcomer to CBS News, an executive producer named Burton Benjamin. “I heard your World Tonight piece,” he said, “and loved it, and I’m wondering, do you have any time today to stop by and discuss it?”

“Sure,” I replied, puzzled but pleased. “When would you like?”

“Well, how about now?”

“I’ll be right there.”

Benjamin, who also had joined CBS in the summer of 1957, had been a writer and producer of news documentaries for RKO-Pathe since 1946. He was a pro, accomplished, experienced, ready for a new challenge. He left the impression, after only one meeting, of being a very decent man, someone you could trust. Apparently enough of his CBS colleagues came to the same conclusion, because in 1978 he was chosen president of CBS News. All told, Benjamin worked at the network for twenty-nine years.

His deputy was Isaac Kleinerman, another experienced documentarian, who had only recently migrated from NBC, where he’d produced a prize-winning, twenty-six-part series called Victory at Sea. Kleinerman’s strength was that he made things happen. Tall, his hair graying, a mustache lending an air of dignity to an otherwise dour face, Kleinerman was, for a film maker used to working under tight deadlines, pleasant, pragmatic, and highly organized.

Benjamin’s office was in the corner of a large suite, home for a television series called The 20th Century. Anchored by Walter Cronkite, a rising star around whom CBS was clearly building a post-Murrow dynasty, the series was relatively new to the Sunday lineup. Successfully launched in October 1957, it was producing a fresh half-hour episode every week. I watched them regularly. I enjoyed their focus on global personalities and problems. The inaugural program, for example, told the exciting story of “Churchill: Man of the Century.” The power of the British leader’s personality, his electrifying rhetoric, and the drama of World War II attracted almost twenty million viewers, a pleasing statistic for the bookkeepers of the “Prudential Insurance Company of America,” the program’s sponsor.

The success of “Churchill” set a high standard for the series. Sunday after Sunday, at 6 p.m., The 20th Century seemed to follow a fixed pattern: a popular personality, a riveting story, and then a concluding climax, all told crisply against a backdrop of archival and original footage. Though Benjamin was widely credited with coming up with the idea for the series, it was actually the brainchild of Irving Gitlin, CBS’s vice president for public affairs. He had read Mark Sullivan’s popular book, Our Times, and decided, on the spot, that its exciting story of America in the early part of the twentieth century would make an appealing television series. In Benjamin’s hands, Gitlin’s idea hit the jackpot, an early rendition of 60 Minutes. It was, the producer noted, with only a trace of embarrassment, “as much a show biz show as any dramatic half-hour.” There was no need for embarrassment. Benjamin had a genius for infusing even a simple tale with drama, energy, and a touch of mystery.

As I headed to Benjamin’s office, still wondering what he had in mind, I remembered a number of the programs I’d recently seen. Near the top of my list were “D-Day,” “Trial at Nuremberg,” and, most gripping, “Riot in East Berlin,” the story of frightened communist leaders mercilessly machine-gunning their people for the sole purpose of protecting their power and privileges. It was no different from the way Soviet authorities crushed anti-Russian riots in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi shortly after Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin, a local hero, in February 1956.

My meeting with Benjamin, in one striking respect, was very similar to my first meeting with Murrow. Just as Campbell had warned me that Murrow was “very busy” and could meet with me for no longer than thirty minutes (the meeting actually lasted three hours, Murrow paying no attention to the clock once we got started), Benjamin’s gatekeeper also informed me that her boss was “busy” and had no more than a half hour. We spoke for two hours.

After a few minutes, Kleinerman joined Benjamin. Both insisted that we drop formalities and use our nicknames. Having none, I remained Marvin, but they quickly became Bud and Ike. They were seasoned documentarians. I knew how to watch a documentary but not how to make one. With their help, I would soon be on a steep learning curve in the new and exciting world of TV documentaries. I’d been put on a fast track at CBS—that was obvious. In a brief time, I had been taught how to write an hourly radio newscast, based on hard news, then a radio commentary, often based on one’s experience and judgment, and now I was being introduced to the news documentary.

For Bud and Ike, the beginning of their tutorial was not focused on the workings of a 35mm camera but the challenge of the mercurial Soviet leader. Like so many others repelled by the rhetoric and antics of Nikita Khrushchev, they chose to spend much of our first meeting asking me about his personality and his policy. Ever since my return from Moscow, in one conversation after another, I found that Americans wanted to know, more than anything else, whether the Soviet leader was “stable.” Was it possible that his antics could push East and West into a war that could easily have been avoided? Was he a clown or a shrewd Russian peasant? Why was he pursuing such a dangerous policy in the Middle East? Did he not know the difference between “national interest” and “suicidal adventures”? I told them that I shared the judgment of almost every Western diplomat I’d met in Moscow—that Khrushchev was a “completely stable” leader, who pursued the “national interest” of the Soviet Union in an admittedly flamboyant but hardly suicidal manner. I told them that I had met and talked with Khrushchev, and he seemed to me to be a classic Russian nationalist, serious about his desire for what he called “peaceful coexistence” with the United States, yet capable of embracing a problematic policy in a troubled part of the world, if he thought he could gain a strategic advantage.

But, if that were the case, Bud wanted to know, how could one explain Khrushchev’s reckless embrace of Nasser? “That could quickly lead us to war,” he observed. While I acknowledged the Egyptian leader might one day drag Russia into a collision with the United States, I thought Khrushchev’s strategic aims in the Middle East were limited—that if he sensed Russia was being sucked into a war with the United States, he would unceremoniously drop his “ally” and withdraw from the battlefield, like the drunken cowboy in a western backing out of a saloon with guns blazing. Khrushchev was no fool, though on occasion he seemed to act like one.

Bud and Ike confessed they were fascinated by Khrushchev as the subject of a possible documentary about the troubled Middle East. Interestingly, the question on their minds was the subject of my World Tonight commentary the night before—how the Soviets used Radio Cairo to propagandize the Arab Middle East.

“We ought to do that as a documentary,” Bud said. “It’s a hell of a story, and Khrushchev’s a hell of a main character.”

Acting instinctively, Ike quickly looked through the fat notebook he always carried with him. His staff called it his “Bible,” a collection of shooting and program schedules, interview dates, and reporter/cameramen travel. “Agree,” he said, “totally agree. Great idea.” He stopped at a page crowded with schedules. “Late October, I think late October is the best time.” Then, spreading his arms out as far as he could, looking like a giant bird about to lift off, he added, “and how about this for a title?” He looked first at Bud and then at me, and, in a soft, serious voice, proposed, “The Red Sell”?

Ike again looked to Bud. “What do you think?”

Bud had an immediate reaction. “I love it,” he said.

And that was that! No more than a few minutes had passed, and Bud and Ike had already agreed on the subject of a documentary, when it would be broadcast, and what it would be called. But, in truth, I still did not know what any of this had to do with me.

“Oh, by the way, we’d like you to be our writer,” Bud seemed to be reading my mind. “What do you think?”

Bud’s question, innocently posed, reminded me of Murrow’s proposal that I write his commentary or Clark’s surprise offer that I broadcast the commentary I thought I’d written for him. On both occasions, I’d been flattered and obviously pleased, but not overwhelmed. I guess I had built up enough self-confidence from my studies at Harvard and my experiences in Moscow to believe I could do the job of writing and explaining Russia to a network audience. “Bud, I’m pleased beyond words, truly, but I’ve never written a documentary.” I hoped my candor would not prick the bubble of his enthusiasm.

“No problem,” Bud smiled. “We’ll teach you. What do you say?”

Here was another challenge; but it was one within my lane, and I thought I could manage it. “You’ve got a deal,” I said, grinning like Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire cat. I shook Bud’s hand, and then Ike’s.

Ever the practical producer, Ike then reminded Bud that he would have to formally request my services from John Day and then, turning to me with a slight grin, added that it would be “nice” if I, in addition, would ask Day’s permission to accept Bud’s offer. “It’s a formality, I know,” Ike assured us, “but let’s do it anyway.” A week later, as Ike had predicted, Day gave his approval. If he had any reservations about my new assignment, he did not express them. Starting on May 1, I would be detached from the newsroom for six months to work as a writer for The 20th Century.

Things were beginning to change for CBS News in Moscow. Within a brief period of time, they would have a major effect on me, but as winter slipped into spring in 1958, I knew only what I read in the papers or heard in the newsroom.

Dan Schorr was expected to return to Moscow in January 1958, as CBS’s resident correspondent, a position he’d held with great distinction since 1955. We had overlapped in 1956, when I worked at the United States embassy as a translator and press attaché. We had become good friends. At one point, Schorr even offered me a job as his No. 2 man in the CBS News bureau in Moscow, a splendid opportunity for a young journalist; but, after much hesitation, I declined, saying I wanted first to finish my PhD program at Harvard. I had promised my mother that before accepting a job, any job, I would complete my dissertation and get my doctorate. She did not want me to be distracted. Yet, less than a year later, when Murrow offered me a job at CBS, I took it without a moment’s hesitation, apparently so thrilled by his offer that I had little difficulty forgetting about Schorr’s offer or the promise to my mother. Clearly Murrow’s impact on me, and many others, had been powerful and lasting.

As required of all foreign correspondents based in Moscow, Schorr applied for his re-entry visa, expecting no problems. But the press department of the Soviet Foreign Ministry responded first with silence and then with an unofficial hint that Schorr would no longer be welcome in Moscow. He was not labeled persona non grata; he was just not welcome. A spokesman, when pressed for an explanation, refused to elaborate, saying only that the problem was Schorr, not CBS. If CBS wanted to continue to staff its Moscow bureau, the spokesman said, it would be wise for CBS to send another reporter.

Schorr, in my judgment, had always been fair in his coverage of the Soviet Union, but he had also been tough. My guess was that he must have offended a senior Soviet official, perhaps even Khrushchev himself. Other foreign correspondents had been similarly tough in their coverage, yet given re-entry visas on request. It was a serious problem, upsetting and frustrating to both Schorr and CBS News. Maybe the explanation lay in the fact that Russia had always been, in Churchill’s words, “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” The Russians never explained their decision, and they did not think they had to.

A month later, CBS gave Schorr another assignment. It was in the form of a defiant poke in Moscow’s eye. CBS moved him to nearby Warsaw, Poland, where he was able to apply his considerable knowledge of Soviet strategy to cover Russia’s restive East European empire. The Russians might have thought they were getting rid of Schorr. They were mistaken. By moving to Warsaw, he had just changed his angle of vision but not the sharpness of his analysis.

But, like any major news organization with global responsibilities, CBS wanted quickly to reopen its Moscow bureau. From its rich stable of political reporters in the nation’s capital, CBS selected Paul Niven, a large, curious, gregarious, well-traveled reporter. He had served in the U.S. Army during World War II. After the war, he completed his studies at Bowdoin College, located near his hometown of Brunswick, Maine, where his father edited the local newspaper, The Brunswick Record. In 1946 Niven enrolled in the London School of Economics while, at the same time, dipping into journalism. He became a stringer for the Manchester Guardian and, a few years later, joined the London staff of CBS News. Wherever he worked, Niven was an immediate favorite. He was candid, thoughtful, an incredibly decent colleague, which I was to appreciate fully when I met him during the Nixon visit to the Soviet Union in 1959.

But, just as Schorr had run into an unexplained, unexpected roadblock on his way back to Moscow, Niven ran into a totally different kind of roadblock several months after his arrival in the Soviet capital. Whether it was one roadblock or another, the net effect was that the CBS bureau in Moscow was left unstaffed from the fall of 1958 to the spring of 1960. During his relatively brief tour in Moscow, Niven faced a large number of bureaucratic obstacles, many normal for any foreign correspondent in a communist capital, several linked to residual bad feelings left by Schorr, and one he had absolutely nothing to do with, yet proved to be his undoing as the CBS bureau chief in Moscow.

On September 25, 1958, CBS ran a Playhouse 90 production of a play called “The Plot to Kill Stalin.” Using real names, characters, and circumstances, the TV drama was made to resemble the actual drama and betrayal surrounding Stalin’s death on March 5, 1953. Playhouse 90 was Hollywood’s version of reality. CBS News was an innocent bystander. Its only connection to Playhouse 90 was that both functioned under the CBS logo, and Moscow was either genuinely ignorant of the distinction between the two, or chose to be ignorant of the distinction. Either way, Moscow had an excuse to again take action against CBS. A few weeks later, on October 12, 1958, the Russians dramatically closed the CBS bureau in Moscow and expelled Niven, who returned to Washington, a victim of Moscow’s real or contrived anger against CBS.

In explaining the CBS/Soviet crisis, Jack Gould, a TV critic of the New York Times, seemed surprisingly more sympathetic to the Russians than to CBS. He ripped into the network for even showing the play, arguing that, in the Cold War, CBS “went beyond … legitimate theatrical” bounds by leaving the “impression that Nikita S. Khrushchev, Soviet Premier, was morally and perhaps legally responsible for the death of Stalin.” This rendering of reality, which more or less conformed to the available evidence, was, in Gould’s view, “ill advised,” reminding him that in 1949 the Russians foolishly staged a play called “The Mad Haberdasher,” showing President Harry S. Truman engaged in wild preparations for a nuclear attack against the Soviet Union. Gould, wrongly in my judgment, equated “The Plot to Kill Stalin” with “The Mad Haberdasher.” One was a well-crafted play, based on what was known at the time by reporters and diplomats; the other was heavy-handed propaganda, based on what Kremlin insiders might have imagined Truman was planning.

On June 1, 1958, over the small town of South Orange, New Jersey, the sky was blue, from one end to the other. All day it seemed only to get bluer. The temperature was Camelot in its perfection, never daring to scale 75 degrees. The breeze was gentle, rarely ruffling a hair. It was as if God wanted the day to be perfect for a wedding. It was.

Mady’s home on Mayhew Court, where the ceremony was to take place, had been magically transformed into both an impressive chapel and an enticing dining room. Her mother, Rose, the smart, thoughtful magician, had rearranged every room. The kitchen, under her direction, had prepared a cuisine that would have been acceptable at Windsor Castle. Whenever I asked Rose if there was anything I could do to help, she would laugh, “Yes, show up.” Mady’s father, Bill, a stock analyst with an active green thumb, had willed the roses and rhododendron in the garden to rise to their full height while welcoming the guests. The garden, in the spirit of the day, never looked greener.

It was quite a day, one Mady and I would always consider a blessing. Rose and Bill were exceptional hosts, making everyone feel at home. They were also intelligent, honorable people, who knew right from wrong. They were always accessible to me for counsel, and after a while, the distinction between in-law and family disappeared.

My mother and father, Bella and Max, who had loved Mady from the moment they met her, enjoyed one of the happiest days of their lives, watching their son marry a bright and beautiful woman. They believed it was no mere coincidence that we both shared an interest in Russian studies. Bashert, my father had concluded, using the Yiddish word for “destined.”

The wedding ceremony was unforgettable. Mady looked enchanting in her long, white gown, a smile never leaving her face. How did I look in my blue suit and striped tie? Acceptable, I guess. But was I nervous? A little bit? Yes. How did I know? After the ceremony, when we all sat down for the splendid feast Rose had prepared, I found that I was not hungry, even though I had not eaten anything since breakfast. The lamb chop was, I’m sure, delicious, but I could not eat it. I watched Mady eat her lamb chop with delicate gusto and then, spying mine untouched, scoop it up and eat it, too. Looking up at me with a mischievous grin, she asked, “Anything wrong? Not hungry?”

After dinner, everyone danced on a floor that moments earlier had been crowded with tables. Mady and I led the way. For hours, we danced, drank, reminisced, gossiped, and giggled. I shall never forget the joyous look on my father’s face when he danced with Mady. Even “fake news” would have got the story right: everyone was having a really good time. Also, I was tickled by the fact that my best man, my brother, Bernie, was likely inspired by my marriage to arrange one of his own. He and the woman of his life, Phyllis Bernstein, had considered marriage many times. Apparently, they did once again, because, two months later, on August 1, 1958, they got married and, an hour later, boarded the Ile de France for a romantic transatlantic cruise to Europe. They were taking the long route to a New York Times assignment in Indonesia.

After a while I noticed that Mady had vanished. I looked around the crowded room and couldn’t find … my wife. My wife? Rose quickly assured me that she had gone up to her room to change into a more comfortable outfit for our drive to New York. For a wedding gift, Rose and Bill had given us a white 1958 Dodge convertible. Wow! When Mady reappeared, she looked even more radiant. “Everything’s ready,” she said. I went upstairs, got the bags, put them in the car, and, as everyone was busy throwing rice and flowers at us, Mady, before getting into the car, threw her corsage of flowers over her head toward an assemblage of would-be brides. One of them actually caught it, bringing cheerful hurrahs from the crowd.

For the first time in our lives, Mady and I were now a married couple driving to a hotel near the United Nations in midtown Manhattan. It was one of my favorites. There we spent the night before flying the next morning to the Caneel Bay Resort on St. John in the Virgin Islands for a ten-day honeymoon.

The summer of 1958 was a busy one.

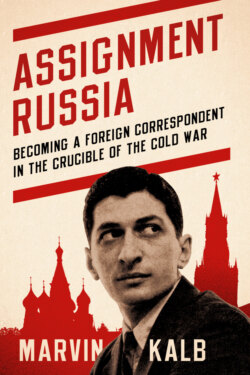

The manuscript of my first book, a loose collection of notes and impressions of my stay in Russia in 1956, had to be edited, and this proved to be a colossal task. The publisher, Farrar, Strauss and Cudahy, had miscalculated how long it would take for me to convert my notes into an appealing book. Publication was planned for early November, and it was a real question whether I’d be able to finish the edit on time. I was then also absorbed with my new assignment at CBS’s The 20th Century. Mady came to my rescue, a pattern that was to recur with remarkable predictability over the years. Although she was already saddled with the task of organizing our new apartment on Gramercy Park South and preparing papers and books for her second year of graduate work at Columbia University, she undertook the tedious job of editing the galleys. With help from a patient Phyllis and a restless Bernie, Mady met the publisher’s deadline with characteristic class, dedication to fact, and love of style. Because my hours were wildly irregular, I was not much help. On more than one occasion, late at night and tired, I would come home to find my fabulous troika of assistants sitting around a bridge table noshing on tea, cookies, and crackers while marking up a galley in desperate need of help.

“How nice,” my brother would exclaim, with feigned exasperation. “Our breadwinner has finally arrived.”

Both Mady and Phyllis were superb editors. They performed a minor literary miracle, transforming my notes into prose and my prose into a rather absorbing account of a young American in communist Russia. Their help was crucial to the book’s ultimate success, as was the context in which it was written. Had Russia not been our principal adversary in the Cold War, had the American people not been fascinated by Khrushchev, and had I not had the extraordinary opportunity to travel from one end of Russia to the other, talking to ordinary people and communist officials, there would have been no book and therefore no boost to my budding career as a Soviet specialist at CBS News.

Henry Hewes, the talented drama critic of the Saturday Review, was the one who came up with the book’s bewildering title, Eastern Exposure. He had proposed it, and I had foolishly accepted it, largely because none of us could think of a better one. Henry thought it might catch a reader’s imagination about the presumed dangers and mysteries behind the Iron Curtain. Mady thought that, at best, it made the book sound like a dull treatise on architecture, more likely to be found in the back corner of a bookstore than upfront on a table reserved for possible bestsellers. Mady proved to be right.

If my late nights were reserved for helping to edit the book, a modest contribution the real editors thought they would have been better off without, my days were nothing less than a crash course in the complicated business of writing a news documentary. I was incredibly fortunate to have Bud and Ike as my professors. They started our tutorial slowly but gradually picked up the pace, and after a few weeks, they were teaching me the delicate interrelationship of word to film.

How does one write for a moving picture? It is a challenge quite different from writing for a newspaper or magazine. The key is to find the words that explain and enrich the film without fighting the film’s visual message—what you are actually seeing in the film. For example, if you had film that showed Khrushchev speaking to a Communist Party gathering, no matter what he was actually saying, you could use it to explain his policy in the Middle East. Likewise, if you had film showing worried Arab faces, no matter what they were actually worried about, you could still use it to convey Arab concerns about Soviet policy. Words use film to convey a thought.

But sometimes a sympathetic film editor would arbitrarily flip the order and encourage me to write whatever I considered essential to the story, and he or she would then go on a hunting expedition in archives or libraries to find the film that would strengthen my words. Of course, there were times when no film could be found. What then? If Bud or Ike considered the underlying verbal message to be essential to our story, then there was always the option of the anchorman simply saying it on camera. Bud, better than most producers, seemed to know instinctively the proper mix of word, film, and story. And if he didn’t, Ike did.

They were exceptional colleagues, always helpful, friendly, and yet serious. They seemed able to sense when I needed help and be there to provide it. When I needed space to research and write, for example, they unhesitatingly encouraged me to shut my office door, forget about everyone else, including them, and not to emerge until I was satisfied that I had copy I wanted them to see and edit. “You’re our man,” they’d stress. “Nothing’s going to happen until we have a script.” I thought for a time that they were just trying to encourage me; but after a while I realized they were telling me the truth: the script was crucial to managing the project. It lay at the heart of all planning. What was to be filmed? Where were reporters to go? Who would be where and when? What was to be promoted? What was to be edited? And, most important, whether at the end of the process there was a documentary worthy of being aired on CBS?

Though Bud and Ike were the key decisionmakers, they often made a point of bringing Cronkite, the anchor of the series, into their deliberations. And their top film and copy editors, too. They even brought me into their deliberations, their way apparently of making sure everyone felt a part of the project. Of course, no one was more important than Cronkite. He was not only the anchor, he was also the rising star at CBS, the reporter who was being groomed to replace Murrow as the brand name of the network.

The transition was not an easy one. Until recently the journalists Murrow had hired to cover World War II—the Sevareids, the Collingwoods, and others—constituted the core of CBS News, those most recognized and heard. Their personal and professional loyalty was to Murrow. In their eyes, he was the network. But, in the late 1950s, as network news expanded dramatically, a new group of reporters, producers, and editors was being hired to carry the CBS banner. Though they all admired Murrow—some even worshipped him—they had no personal loyalty to him, and a number began slowly to rally around the new standard bearer of the network. Bud and Ike, as relative newcomers, were among those who hitched their futures to Cronkite, and they chose well.

Cronkite was an accomplished, experienced journalist who transitioned from print to television with remarkable ease. Like Murrow, he too had covered World War II, working as a correspondent for United Press. When, in February 1943, the United States planned to bomb the German submarine base at Wilhelmshaven, a dangerous undertaking, Cronkite fought successfully to be the pool reporter. “The anti-aircraft fire was intense,” he later reported. “Golden bursts of explosives all around us, dissolving into those great puffs of black smoke.” His war reporting was outstanding, winning Cronkite the prized assignment after the war of covering the Soviet Union, an ally during the war, the principal adversary after the war. While in Moscow, he learned a lot about communism and diplomacy, which prepared him for yet another major assignment. Cronkite was sent to Washington at the dawning of both television news and the Cold War. It was then that he made his graceful switch from print to television. The term “anchorman” was invented for Cronkite in 1952, when he covered the Democratic and Republican presidential conventions. Five years later, he was named anchor of The 20th Century series, and in 1962, he replaced Douglas Edwards as anchor of the CBS Evening News, a job he held for nineteen years, covering presidential campaigns and conventions, wars and revolutions, weather and space launches. He did it all with a smooth, easy professionalism that brought kudos to CBS and the affectionate nickname “Uncle Walter” to him.

Bud and Ike used to enjoy boasting that Walter’s historic career really began at The 20th Century, where week after week Cronkite anchored a news documentary that illuminated an important moment in American and global history. They believed the series helped introduce Cronkite to the American people and to CBS’s top management. It also helped introduce me to Cronkite, a friendly professional relationship that lasted more than twenty years. On many occasions, while composing “The Red Sell,” Bud, Ike, Walter, and I would work together, a cooperative quartet, to produce a timely and insightful documentary on Russia’s exploitation of Radio Cairo to spread communist propaganda throughout the Middle East. Often, taking advantage of Walter’s own experience in the Soviet Union, I would run my copy past him before showing it to Bud and Ike. Walter helped in two very practical ways: first, providing his editorial perspective on Khrushchev’s motivation and policy shifts, and second, reading my copy to see if its rhythm conformed to his broadcast style. Though I was very much the newcomer to the news business, Walter appreciated my knowledge of Soviet policy—he treated me with respect; and I came to trust his judgment and consider him a valuable colleague. I was still very much a “Murrow man,” but I could see how Cronkite could easily slide into the lead role at CBS News, once Murrow, for a variety of reasons, including a growing disillusionment with television news, chose to leave CBS in January 1961 and join the new Kennedy administration.

Since 1953 I’d been reviewing Russia-related books for the Saturday Review. I started as a graduate student at Harvard and continued during my short career as a diplomat in Moscow, and now, at CBS, I blended book reviewing with my new responsibilities as a journalist—and benefited enormously. By reading and reviewing books written by notable scholars and journalists, I was able not only to keep abreast of the latest developments in the Soviet Union, which was helpful in writing my scripts, but also to develop the reputation and influence of a critic. Writers seeking recognition called not once but two or three times, trying to persuade me to review their books. Then they went one step further, having mutual friends call me. Several of these writers were professors I had met or read; yet unashamedly they too called, pleading for the review that they hoped would enhance their position at a university or their reputation in the field of Soviet studies. I marveled at the lengths writers would go to persuade a critic to review a book—from repeated calls to flowers to personal letters to offers of a steak dinner, almost anything. I tried to explain that I was not the one who selected the books for review, but few of the writers would believe me. “You can do it,” they’d plead. “You can do it.” I couldn’t. Even on a few occasions when I really tried, I couldn’t.

Historian Bernard Pares was especially helpful when I tried to explain the roots of Khrushchev’s policy in the Middle East. He had spent more than sixty years studying and writing about the history of this fascinating country. He was, according to his son, Richard, “a man with a mission: to interpret Russia to the English-speaking world, and even to bring the two worlds into political partnership with each other.” By the time Pares died in 1949, he knew he had failed: the Cold War having already chilled the wartime alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union, but he considered the effort to be worthy of his time. If through his books and speeches he could help head off a nuclear war between the two superpowers, then he felt he had no alternative—he had to try. As well as anyone, he explained the reasons why Russia, and now the Soviet Union, often moved its ambitions south toward Turkey and the Dardanelles and, through them, to the Mediterranean, where, if possible, it would exploit the economic and strategic riches of the region to magnify the glory of Mother Russia. The tsars had persuaded themselves that they were in desperate need of a warm-water port. Bottled up in the north by an aggressive Sweden and a powerful Prussia, whether governed by tsars or commissars, Russia very often moved south, stumbling into one war after another.

Pares was one source; there were others. I wanted my copy for this documentary, my first, to sing, to be appreciated as distinctive, and I hoped the wisdom of historians could help me. Bud and Ike liked my approach. Cronkite loved it. “Marvin,” he’d say with a grin, “you’re making me look good.” I couldn’t have been more pleased.

Not just Pares; for the Saturday Review, I reviewed many of the classics of Russian history, literature, and government:

Ukraine under the Soviets, by Columbia University’s Clarence A. Manning. This was his forty-fifth publication, but it was “hurried … and hampered by a Ukrainian bias,” I reluctantly concluded.

Current Soviet Policies, by Leo Gruliow, editor of the “Current Digest of the Soviet Press,” who for this book collected, edited, and translated major Soviet documents. “With the Iron Curtain still impenetrable,” I wrote, “the printed Soviet word is still the best available key for gaining admission into the Soviet system.”

Soviet Taxation: The Fiscal and Monetary Problems of a Planned Economy, by Franklyn D. Holzman, a former colleague at Harvard’s Russian Research Center, then a professor at the University of Washington. His book was, I said, a “scholarly and exhaustive analysis of Kremlin tax policies,” valuable to the expert but no easy read.

Soviet Military Law and Administration, by Harvard’s Harold J. Berman and Miroslav Kerner. Though Soviet law was “manipulated opportunistically” by the state, they believed, its “maintenance was nevertheless crucial for the perpetuation of the state.” I thought their vision of the Soviet state was naive, but the book was still an important, if controversial, study.

The Origins of the Communist Autocracy, by Harvard’s Leonard Schapiro, another colleague. “Sound scholarship and refreshing writing,” I said. It is a “literate and important examination of the political opposition to Lenin and the Bolshevik state from 1917 to 1922.”

Leninism, by Harvard’s Alfred G. Meyer, another of my professors. His study was an “excellently documented, thoughtfully conceived, beautifully written and keenly stimulating analysis of the ideology that has rocked the world.” Meyer deserved the rave review.

Gogol: A Life, by David Magarshack, who wrote the “tragedy” of Gogol’s life was that, though born in an Orthodox Ukrainian village and having Polish Catholic roots, he wanted nothing more than “to save Russia, an idea completely divorced from reality but that obsessed him to the exclusion of everything else.” While true, Gogol was still a brilliant, incredibly gifted writer.

Russian Liberalism, by George Fischer, a professor at Brandeis University, who “refutes the cliché” that Russia nurtured only “the extremes of political thought” by exploring the important political and economic reforms of the latter half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Many of these reviews were published as “shirttails,” the term editors used for short reviews, roughly 400 words in length. They would be attached to a much longer review of books that editor Ray Walters considered of greater interest to Saturday Review readers. Books on the Russian economy or Soviet law rarely got more than a shirttail.

Question: Would my own book, Eastern Exposure, being readied for publication in early November 1958, be worthy in Walters’s judgment of a proper review, or of a shorter shirttail review, assuming, of course, he considered it worthy of a review at all. Like so many other books, it could be destined for the dusty desks in the back of a bookstore, ignored by everyone except friends and family. Still the optimist in me believed that the subject alone—an American in Soviet Russia during the Cold War—would almost guarantee a review.

Another question: Would I, like so many other writers, ever feel so frustrated by the failure to get a review that I’d call a reviewer and plead for one? I had received such calls from other writers. Would I do what they did? I decided that I would not. I wanted to believe that Walters would assign my book to someone, if for no other reason than to ratify his own judgment that by selecting me to review so many of his Russia books, he had chosen someone who could write his own Russia book and, for his effort, receive a respectful critique. But that was yet to be determined.

For the moment, it was another book about Russia that was exciting the literary world—Boris Pasternak’s magnificent Doctor Zhivago. It was slated to be published in the Soviet Union in October 1956, but never was.

The Union of Soviet Writers, which censored all Soviet literature, had ruled, with ironic accuracy, that the novel “casts doubt on the validity of the Bolshevik Revolution … as if it were the great crime in Russian history.” And, as such, the authorities ruled it could and would not be published in the Soviet Union. But an unexpurgated copy of the manuscript made its way to the Italian communist publisher, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli. The Russians angrily demanded its return, but Feltrinelli artfully played for time, refusing to give it up. Apparently more the businessman than the ideologue, he knew Pasternak had written a certain bestseller, and he seized the honor to be its publisher. In the fall of 1957, Doctor Zhivago burst into print in Italy, producing a literary whirlwind of admiration and controversy. A year later, over the Labor Day weekend, the good Doctor leaped to the top of the best seller lists in the United States and the rest of the English-speaking world. Overnight Zhivago and Pasternak became household names for literary genius and ideological resistance.

Harrison Salisbury, who had covered the Soviet Union for the New York Times, wrote the major review for the Saturday Review. He gave Zhivago a rave. I wrote a long shirttail essay on Pasternak, once praised by Mayakovsky as “the poet’s poet.” Doctor Zhivago was Pasternak’s only novel, which is one of those hard-to-believe facts. Spry at age 68, fluent in English, French, and German, a student in Berlin of Western philosophy while still a teenager, Pasternak was a lonely outpost of literary independence on the Soviet landscape. While most writers adjusted to Stalin’s cruel rule, he maintained a stubborn aloofness. For decades, he just stopped writing, spending most of his time translating Shakespeare, Shelley, and Goethe into Russian. His father had been a renowned painter and his mother an accomplished musician. Pasternak’s upbringing was among pre-revolutionary Russian intelligentsia, many of whom abhorred communism.

Pasternak never fit into Soviet life; he was, till the day he died, a circle in a square world. With his wife, he lived modestly in Peredelkino, a writers’ colony in suburban Moscow. Only after Stalin died in 1953 did Pasternak feel comfortable enough to return to his desk and write one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, the story of a disillusioned doctor struggling to live and love in the bloody aftermath of the Russian Revolution. What so profoundly disturbed the Kremlin was Pasternak’s dismissal of the historic importance of the revolution, showing no admiration at all for Marx’s hyped utopia, yearning instead for the right of the individual to choose his own path in life. For Pasternak, it was always the individual versus the collective, freedom versus tyranny, a battle he seemed destined to lose but one he felt certain he had to fight. His only weapon was words.

The story of Doctor Zhivago’s publication needed no salesmanship in a New York newsroom. It was a compelling story, and both Murrow and Clark quickly accepted my offer to do a commentary for their radio broadcasts—in fact, as it turned out, several commentaries, as the story grew over the next few weeks. Pasternak was hailed throughout the West as a “literary genius,” while Soviet propagandists denounced him as a “decadent formalist.” Pasternak, under pressure to explain his approach to writing the novel, stressed, “I am not a politician. This is not politics. But every poet, every artist, must somehow grope for the trends of his time.” And, as he groped, he became more and more an unwitting symbol of the Cold War.

Then, on October 23, 1958, out of the gray, neutral skies over Stockholm, came an explosive announcement. The Swedish Academy had awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature to Pasternak. It was bulletin news everywhere except in the Soviet Union, where Doctor Zhivago still had not been published. The Kremlin, with this announcement, was placed in an awkward, embarrassing position, no more so than Pasternak himself. He would probably have accepted the prize, but he knew, almost instinctively, that the Kremlin would prefer that he reject it. Almost as confirmation, the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party dispatched another writer, a neighbor named Konstantin Fedin, to “suggest” to Pasternak that he categorically, in writing, reject the prize, as if it were a dreadful Western disease. An uncertain Pasternak pleaded for time, leaving the inescapable impression that he might actually accept the prize. Shocked, the Kremlin went into overdrive.

First, the Union of Soviet Writers met and officially condemned Pasternak and demanded his expulsion from the country.

Then, on October 26, Pravda, the Soviet Communist Party newspaper, ran a blistering editorial entitled, “Reactionary Propaganda Uproar over a Literary Weed.” “The snake is wriggling at our feet,” it said. “It is irresistibly drawn downward to its native swamps where it enjoys the odors of rot and decay … warm and comfortable in the poetical dung waters of lyrical manure.” This ugly attack, typical of others hurled at Pasternak, affected his health. For a time, he went into a depression, not eating or sleeping.

The following day, unable because of ill health to attend a critically important meeting of the Union of Soviet Writers, he sent a letter to the Executive Committee, in which he tried to explain his belief that it was acceptable for his main character, Zhivago, to be both a critic of the Soviet system and a loyal citizen. “I have a broader understanding of the rights and possibilities of a Soviet writer,” he wrote, “and I don’t think I disparage the dignity of Soviet writers in any way.”

Pasternak’s letter won no friends. Twenty-nine writers, once among his closest friends and admirers, rose as one to denounce his “immeasurable self-conceit.” They described the book, a bestseller everywhere, as “the cry of a frightened philistine … false and paltry, fished out of a rubbish heap.” The writers then switched from what they might have considered literary criticism to accusations of political betrayal, speaking of Pasternak’s “political and moral downfall, his betrayal of the Soviet Union, his fanning of the Cold War.” Whipping themselves into a fervor of feigned ideological purity, they concluded their meeting with the unanimous decision that Pasternak be stripped of “the title of Soviet writer” and “publicly expelled” from the Writers Union.

Pasternak had not anticipated so sharp and brutal an assault. He went into a deeper depression and actually considered suicide. “I cannot stand this business anymore,” he confided to friends. “I think it’s time to leave this life. It’s too much.”

But, on October 29 he chose a more benign course of action. He sent a carefully crafted letter to the Swedish Academy. Only a Kremlinologist could have interpreted its between-the-lines message. “Considering the meaning this award has been given in the society to which I belong, I must reject this undeserved prize which has been presented to me. Please do not receive my voluntary rejection with displeasure.” It was signed simply, “Pasternak.” (Italics are my own.)

The Swedish Academy, sensitive to Pasternak’s position, decided its reply would be brief and understanding. The Academy “has received your refusal with deep regret, sympathy and respect.” Clearly, each understood the other.

But Khrushchev was still in an agitated state. Clearly embarrassed by the global uproar over what he derisively referred to as “that book,” the Soviet Communist Party leader ordered the trash-talking head of the Komsomol, Vladimir Semichastny, to attack Pasternak before a hastily assembled group of 12,000 young Russians in Moscow’s Sports Palace. For many of them, Pasternak had been a cherished poet and translator. Semichastny’s task was to belittle Pasternak, to diminish his literary standing, to transform him into a stranger in his own land. His attack was carried “live” on Soviet radio and television.

“Even in a good flock,” Semichastny began, “there may be one lousy sheep.” Obviously that was Pasternak, “who has decided to spit in the face of our people.” He has written a “slanderous so-called novel” that “gladdened our enemies,” leading to a Nobel Prize “for slander, for libeling the Soviet system, socialism and Marxism.” Semichastny then changed his description of Pasternak from a sheep to a pig, declaring “no pig would do what he did.… He has defiled the place where he has eaten; he has defiled those by whose toil he lives and breathes.”

Semichastny concluded his attack by expressing “my own opinion” that Pasternak, described as an “internal emigré,” become a “real emigré” and “go to his capitalist paradise.” The audience, thus prompted, burst into applause. “His departure thus from our midst would make our air fresher.”

The next morning, a deeply demoralized Pasternak sent a letter to Khrushchev begging his forgiveness and pleading for his permission to remain in his home. He sent a similar letter of apology to Pravda, ensuring its broad distribution.

Pasternak’s travails remained an absorbing news story for many months. I heard from friends at The 20th Century, where I was finishing a final edit of the documentary script about Khrushchev’s propaganda push into the Middle East, that CBS was planning a TV special about Pasternak and his book. It was to be part of a Sunday series anchored by Howard K. Smith, another of Murrow’s World War II colleagues. I knew nothing more about it. In those days, Sunday afternoons were not reserved for professional football—that was an era yet to emerge; they were still reserved for public policy programs that won prizes and positive reviews but rarely did they generate the TV ratings that networks craved. Though I had no reason to believe I would be included in the special, perhaps as a writer or analyst, I must acknowledge that in a corner of my mind, I entertained the slim hope that I would be. It would be another confirming marker that I was getting closer to being considered CBS News’s specialist on Soviet affairs.

One day in late October, as I was transitioning from The 20th Century back to the newsroom, my agent, Edith Haggard, called with good news. She had heard from one of her friends at the New York Times Book Review that they would be running a review of my new book, Eastern Exposure, on Sunday, November 2.

I erupted with joy. “Fantastic!” I shouted. “That’s great.”

But, after a moment of cautious reflection, I asked, a large question mark in my voice, “Is it a good one?”

Haggard replied coolly that she did not know and brushed aside my concern. In her judgment, any review was better than no review, and she added, “and there may be one in the Post too.” The click at her end of the line suggested she’d had enough or had to make or take another call.

Still, I could not help but wonder whether the reviews would pan the book or praise it; and if they panned it, would it be a cruel, gleeful critique, or a gentle one? And how would I take it? Still, if Haggard was right, two major newspapers were showing interest in the book, which was a step in the right direction, even if I didn’t yet know whether their interest also meant approval.

November 2 was going to be a big day for another reason too. My first big step into TV news—The 20th Century documentary I had written, “The Red Sell”—would be shown on CBS. How would it be received?