Читать книгу The Ocean House - Mary-Beth Hughes - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

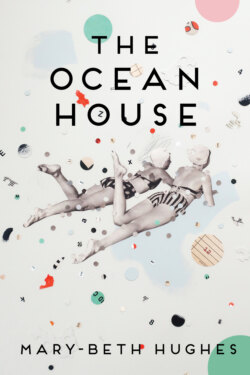

ОглавлениеThe Ocean House

They were tiny girls lying on their bellies by the wide windows of the playroom, spying on their mother far below. She tiptoed along the seawall, holding steady on puddled dips and sharp edges of the black jetty. Waves burst and sprayed at her feet. The girls pressed in close, touching clouds and crabs etched in the glass along the lower rims. Their fingers worked into the grooves as they watched their mother—so light-footed, her bathing suit beneath a sundress—climb over the fence between the neighboring beach club property and their own. She’s a fish! their father liked to declare, but she didn’t like to be inside the ocean. She preferred salt water in a swimming pool where she could see the beginning and end.

Midmorning, Mrs. Hoving, despite her bad hip, walked all the way down the back stairs to retrieve milk and peaches. Their playroom was a round attic room on the turret end. But directly below, the grandest room of the house was empty. In the master bedroom a plinth raised the bed so high that, waking, their mother might see the waves first thing. Above the bed, a built-in carved canopy of shells and rosebuds lifted by four columns all painted white. The vista windows had ribbons of more rosebuds in pale-pink stained glass; the thorns were blunt and blue. A sleeping place for a sea queen. But their mother didn’t care for it. Thought it corny, trite. The window shade manufacturer’s silly dream for a wife who left him anyway. Then he went bankrupt. Why would she want to sleep there?

Their mother was content in a regular rectangular bedroom with cross breezes. Besides, the grand circular bedroom with the plinth, the canopy, the flat pink glass roses and stubby thorns was haunted by a small boy who swung by his feet and made slurping noises nibbling at the sleeper’s nose. Their mother said he liked to be left alone.

Of course they wanted to know how old he was, but she couldn’t say, which was frustrating because age was crucial to them at the time. Courtney was five, nearly five. Paige was three. Their mother was twenty-seven, so an old woman she said. Their father twenty-eight. But they were a year and a half apart, like Courtney and Paige. Mrs. Hoving claimed to be 103.

On the turret side of the house, below the haunted bedroom, was the circular dining room. Lower still, a cellar of sand and rock, entirely off-limits. But in the bright round dining room, where they were free to come and go, their mother hung a new wallpaper. She’d imported the white herons standing in the lime-colored reeds from Japan. The house made me do it, she said. And that made sense because it looked, when she was finished, as if it had been here from the start. Something to appease the fleeing wife, the broken husband, the hungry boy. All of them.

Don’t be flip, said their father, as if she’d said something cruel. Mrs. Hoving didn’t allow cruelty. Nor did their mother. Their father could be changeable on this point.

The year was 1962. The house except for the newly arrived Japanese herons—and their bending inquiring white necks—was ninety years old at the time but seemed much older. It was the last of the great oceanfront houses left in Long Branch.

Built in the same exuberant era, the Beach Club aimed for grandeur, too, with its herringbone boardwalk and a vast saltwater pool, the cunning trellised card room, the vaulted seaside dining terrace, the clubhouse itself, like a vast white Victorian wedding cake. A cliché, said their mother. It was meant to seduce those living in the houses who had plenty to keep them at home. But later, with the towers, business improved.

The Beach Club stood directly north of their house. Its property continued for about an eighth of a mile until it petered out—their mother shrugged—at the tennis courts, then the high jagged jetty wall picked up again and continued along the Ocean Avenue for a while before crossing the town line into Sea Bright, which was filled with newer beach clubs vying for sunbathers and swimmers. To the south toward Asbury Park, all the new slinky apartment towers lined up, with concrete balconies like gray tongues that stuck out on the ocean side only. Tucked in, here and there, were the few other survivors. A nunnery. Two oil tycoons in retirement. Syrian Jews. And next to them, the Lebanese Catholics. Houses like their own, shingled and sometimes sagging, behind iron gates and high hedges.

The Beach Club was eager to tear down their house and build its own tower. Sheep, said their mother. Sheep with demolition kits.

When the house first came up for sale—something quick and private to settle a complicated estate—the club lost the bid. And their father won because, their mother said, of his exceptionally good character. And also the windfall that came to their mother quite by surprise, a gift sent from overseas. Money that had once been her own mother’s now all these years later released to her. They paid cash, she told the girls, and Courtney liked to think of a wheelbarrow full of bills and coins.

The club president never gave up about the house. He’s a terrier! said their mother. A sheep, a terrier, a snake, the shape and sound of his threat changed day to day. Baa, woof, hiss.

At least he can’t sue, said their father. He can only send spiteful letters.

But he can, true? He may do much worse.

This over breakfast coffee in the human-scale kitchen, another rectangle, whitewashed beadboard to the chair rail, then blue plaster walls. And bluish morning light off the ocean through the windows to match. Mrs. Hoving scraping carrots into shreds at the sink. For later. Their father would welcome a lawsuit. That would settle things for good. Though of course there are no grounds, he said.

But there were. And this was something Courtney would look into much later, the shady deal that briefly gave them their beautiful house and then allowed them to lose it. And she would think about the wheelbarrow full of money.

Still, at the time, the girls understood a truce had been struck with the Beach Club about their mother’s essential swimming. She was allowed in the pool. Soon, she would bring them, too. When they were ready to learn to swim. The girls believed all of this was an extraordinary concession. For their mother, who deserved special treatment. But it turned out they’d had a membership all the years they lived next door. Something that evaporated when they left and moved inland away from the ocean. As if without their mother they were no longer welcome at the Beach Club. So the special-treatment theory held steady for a long time.

In those years, they’d never use the club’s front entrance. Like their mother, they’d learn to pick their way over the slick jetty, a shortcut. By their own front gate, a too-grand affair of iron curlicues, black-green cypress spires grew high enough to block out the sight of the summer traffic and to screen their mother’s chosen bedroom from any prying eyes.

She especially liked the room for its red marble mantle, which reminded her of London. In summertime, the windows would be thrown open and the hum of car engines on the avenue and the bang and hiss of the waves would rush in all together. The lion-skin carpet at the foot of her bed had a doggy smell.

The only pet you’ll ever have, my loves, said their mother, who was against keeping animals because of what had happened to her dog in the war.

As they grew older, their mother spoke more about her life in London. One morning in London, for instance, their grandmother Bess—whom they’d never meet, though Paige had her dark round eyes exactly—one morning their grandmother put their mother, seven years old, on a train to the country. With other girls just like you their mother told them. She had a fat ham sandwich and a clean blue dress folded in a paper sack. Ten weeks later she came home to a crater in the sidewalk. And all because their grandmother Bess refused to fold up her food tent just for the sound of yet another sputtering engine in the sky. Beneath a white fluttery tablecloth strung up on poles to keep out the sun overhead, Bess gave sandwiches to anyone in need. Her card table set at the end of the front walk. Samson the beagle lay at her feet, ready to ward off danger if it came along. From above, among gray stone houses and gray roads and rooftops the white tablecloth must have shone clear.

But when they were still tiny enough to keep to the playroom, the most frightening thing they believed their mother knew was the hungry boy who swung upside down over the deserted master bed. She was keeping clear of him.

Far below, their mother on the tips of her toes stepped off the seawall, her sundress fluttering away from her in the wind, her famous black swimsuit just visible when she straddled the Beach Club fence. Mrs. Hoving’s cool hands fell on their shoulders smelling of peaches. Come away from the window now, girls. Let your mother have a bit of peace.

Later their father moved them two miles inland. The new house in the neighborhood behind Our Lady Star of the Sea had a flat lawn, closets with louvered doors on metal tracks, and a screened-in porch where their new stepmother, Ruth, would set up shop, she said, until it was time to switch the thermostat up in the fall. Then her friends would visit in the den. If the girls needed permission for anything, they always knew where to find her. She had a voice that carried and wanted them to talk louder, too. And stop walking so much on their tiptoes. They were quiet girls, especially Paige. The elder, Courtney, ten turning eleven when they moved to Honeysuckle Lane, often spoke for them both now.

Once they were settled in, their father decided he’d keep the ocean house a while longer.

What for? asked Ruth, taken aback. You won’t see a better offer. This is it, the sky-high limit. Trust me.

Their father winked at the girls. Oh, I might hear something a little more persuasive. And they smiled. This was the old game they knew.

Okay, said Ruth. Not my beeswax.

From Honeysuckle Lane the girls could walk themselves to school. Ten minutes flat, back door to Star of the Sea parking lot. A new school for the girls, they were Catholics now, like Ruth. Their mother had been agnostic. Just in case, she’d said. Their mother let them wear shoes whenever they liked. Ruth handed out their school shoes only in the mudroom. She didn’t want them tracking in the muck of their shortcut through Mr. Kemp’s apple orchard. The whole house would stink of rot, like stale cider then.

Mr. Kemp’s shortcut was mostly avoided by the neighborhood kids. The old orchard was overgrown and dense with pricker bushes and poison sumac. Paige spotted three snakes and a water rat on a single afternoon. Once they saw a group of boys from the seventh and eighth grade smoking cigarettes and sitting on a fallen tree trunk by a half-collapsed wood structure, an old outhouse. A thorny holly sealed up the door. It was a windbreak, and the boys squeezed the still-lit butts though the cut sliver moon in the door, as if daring the place to catch fire. Courtney and Paige walked the farthest path then, heads down to avoid notice.

But one day Courtney had detention after school. While Sister Joseph was sorting the attendance book entries, a counting mistake she couldn’t make sense of, Courtney let out a fake sneeze that had words embedded inside: Aren’t you? Aren’t you fat?

Silence, Sister Joseph said. Heads up.

And Courtney whispered something about the knot in Sister’s forehead, a mysterious lump that popped out between her eyebrows.

Don’t move! shouted Sister. Freeze! Then, when she’d fully assessed the class: Courtney Ruddy? Right here, right now.

Sister pointed to a spot near the chalked detention list. Add your name and stay right there.

And Courtney felt her face go hot red with the effort to keep it still, not to laugh or cry. Made to stand against the blackboard until dismissal and not wriggle, then given the task of stacking the chairs in the corridor, all thirty of them.

On the way home, her boots unzipped, her coat unbuttoned, seeking penance, Courtney heard her sister Paige’s voice. A shiver of a laugh for the kind of ugly joke they might tell each other in the night, a supposition about Ruth and her wide fanny. Or the big bosom they liked to wrap their arms around, Paige in front, Courtney behind, then re-create the shape of, amazed. It was that same laugh, a bit of a hiss, but she couldn’t see Paige. The trees in October were already scratchy tangles against a gray sky, so there was no place to hide except the outhouse. And there she was, standing with her back to the outhouse door, a big boy—maybe a seventh grader, maybe even an eighth grader—pressed against her. His arms stretched high, fingers splayed on the wood. Paige’s head stuck out just beneath his armpit. He angled his big body like a plank into Paige. Don’t, she said, without a laugh now.

One big boy said, He’s only playing. But Paige said, I can feel his thing!

Courtney kept walking to her sister. She didn’t speed up and she didn’t slow down. She closed her coat carefully as if the motion might break something. When she was near enough to be heard, she said, Hey?

They all looked at her at once.

Are you all right? she said directly to her sister. Courtney made her eyes simple. Pretending she was just a wispy leaf, maybe orange colored, that had landed on Paige, nothing to be scared of.

The boys looked at Courtney. There were more than she’d thought; some had cigarettes burning.

Are you okay? Courtney tried again.

No one answered her. And when Paige looked at her, her eyes went blank, as if she were a door Courtney couldn’t go through today.

Courtney didn’t want to say her sister’s name, in case the boys didn’t know it, so they wouldn’t be able to find her later or the house on Honeysuckle Lane. Should I wait? she said to Paige.

Nope, said a boy with black hair and pink cheeks. Everything’s fine. We’re playing a game.

Paige, under the boy’s armpit, looked so small. At least her coat was buttoned. Go home, Courtney. It’s a game, she said, but Paige sounded like the doll talking when the string was pulled: Go home.

Courtney turned around and started walking, feeling the way she had earlier today when everyone looked at her as they left the classroom. Sister Joseph had succeeded in marking her as repulsive as her own wart. And now the big boys could see this about Courtney, too. It was as clear to them as Sister Joseph’s protuberance. Ruth’s word, giving the big lump with gray hair sprouting out like a spare eyebrow some dignity. Courtney was a protuberance. The boys liked her sister and wanted nothing to do with Courtney.

But then maybe Paige was only faking. She was often a liar now. They both were. Courtney spun back whether they wanted her to or not, but they’d taken their game elsewhere. Quiet as snakes, they’d already vanished from the orchard.

When Courtney got home, Ruth was serving sweet pickled onions on pumpernickel toast rounds in the den for four o’clock cocktails. She waved Courtney upstairs, sighing: Homework, please.

Don’t you care where precious Paige is? whispered Courtney.

But Ruth was repeating her sigh, more amplified now for her friends. Upstairs in the room she shared with Paige, the lavender flounce on Courtney’s twin canopy bed looked stupid. She ripped the ruffles off hoping to get rid of it once and for all. But she left the top of Paige’s bed intact so she could make her own decision.

In the ocean house their mother had been against ruffles. Forced down your throats your entire lives, why start now. They were dressed like little English girls in gray and navy blue, good linens, good wools. They wore their hair in single braids, tied beginning and end with white cotton ribbon. Mrs. Hoving did the brushing and the braiding and the baths with the transparent brown soap.

Mrs. Hoving vanished when they moved to Honeysuckle Lane. They asked their father where she’d gone. And Ruth answered quickly: To Newark, to her family. Lots of trouble there and she’s the only one with any sense.

Would Mrs. Hoving be coming back when the trouble was over?

Now why would she, asked Ruth. And the girls looked to their father for confirmation, but he was busy watching out the window, guarding the flat lawn.

After the day in the orchard with the boys at the old outhouse, Paige told Courtney she wasn’t allowed there anymore. The boys have made it out-of-bounds.

For both of us?

No, Paige said. Just for you. And just in the afternoon. The morning it’s still fine to cut through.

Which meant Courtney now had to take the long route home all the way down Oakes Road to the far end of Honeysuckle Lane. She was the only one walking this way. But soon Andrew Kennedy cycled slowly around her, an eighth grader with big flat hands and coat hanger shoulders, stiff and pointing. A shorter, thinner older brother’s school blazer riding up to reveal the pale skin above his flannel trousers. This bike’s only four years old, he explained. It’s still perfect. As if Courtney wanted to know. He tipped sideways to tighten the loops around her, stinking the air with pockets of his breath and sweat. He made her dizzy, just to look at him. You don’t frighten me, she said. They were out in the wide open and any neighbor or even Ruth might drive by in an instant. But every day now included a blister of time with Andrew Kennedy and his chipped green three speed.

What does he want? asked Paige, from the top of her pristine bed. She always made it up carefully and slipped into the sheets and blankets at the last minute just to sleep.

He must be lonely, said Courtney, though it had never occurred to her before. Those boys still in the orchard?

Not really, said Paige. Then she was pulling back the bedspread as if it stank of something and inserting her skinny legs one at a time into Ruth’s stiff bleached sheets.

Courtney was the oldest in the fifth grade at Star of the Sea. She’d been left back the year they moved to Honeysuckle Lane. Now Paige in fourth had almost caught up to her. Courtney had started out smart but now she was in the bottom percentile.

She’s not much of a trier, Ruth explained to their father. Ruth had done her best. But given the steep task and the short time allotted, there was talk of cutting losses. Sometimes the older takes the brunt, she said. We have to face facts.

And Courtney, folded into her hiding spot between the back of the tweed sofa and the heating vent, assumed she’d be sent away like Mrs. Hoving, so the more promising Paige could be given more of what Ruth had to offer.

Paige is a sweet thing, so helpful. But it was the dead of winter, their father pointed out, as if that were relevant. As if when the snow lifted, Courtney might bloom again. This point was met with silence.

When the spring finally came, the orchard filled in with blossoms and then the buds of tiny apples-to-be. The fruit already at Mr. Kemp’s farm stand was imported. Ruth shopped there and one evening told their father that Mr. Kemp had made a pass at her, had tried to rub his nasty fingers where they don’t belong.

The girls didn’t believe it.

Handed me my bag of cherries and nearly twisted a you know what off me. Their father laughed, and Ruth laughed, too.

Oh, such a rookie, he said.

At afternoon cocktails, Ruth often related the woes of her new life. The girls were stubborn, selfish, contrary, though never rude. I’ll give their mother that much, she’d say. She taught them manners. Too much, if you ask me.

Never rude? Of course not! Their mother was born in England, her own mother, Bess, gone early in the war. Her father earlier still.

Sometimes Ruth pumped them for information so urgently the girls wondered if their father ever told her anything at all.

They do the snaky dance and that’s it, said Paige. Courtney caught their father in the kitchen rubbing his front against Ruth’s bottom. When Courtney arrived with dessert plates he wheeled back and pretended a golf swing. He doesn’t even play golf, said Courtney later to Paige.

One thing Ruth really wanted to know was who found their mother first. She didn’t lead up to it, just asked outright. So? Ruth pressed. The girls looked astonished. Or at least that’s how Ruth described them to the afternoon ladies. Mouths hanging open, eyes like marbles, she said. She had her work cut out for her with those two, all right.

Sometimes a shock like that does brain damage, she said.

The women agreed, but also said they liked her new egg salad. Catsup, Ruth confided. It’s my secret.

When Ruth whimpered late in the night on the other side of the wall and woke up the girls, they decided that their father was shaking catsup on her bottom. This was the funniest thing in the world but also nauseating. Paige would go into the yellow bathroom and put her finger down her throat until nothing came up but green. She’d come back into bed, stinking of stomach juice.

Are the boys nice to you? asked Courtney.

What boys? said Paige.

Let me show you something, said Courtney. She got up and gathered her seashells off the top of her dresser. Sometimes, if I put these in a special order—she arranged a circle of shells with two brownish sand-encrusted fragments in the center—Mama just appears.

Shut up, said Paige.

Not in the firm way, more in a dreamy way.

On your canopy, I suppose. Just shut up.

That was only a story, said Courtney. That was pretend. Then she swept up her shells and put them in a drawer where they wouldn’t get contaminated.

It wasn’t Paige, as they’d sworn to Ruth, but Courtney who first found their mother. And right away, Courtney knew she was the lucky one. Worse to have to make up a picture in your mind to fill such a giant meaning. The actual picture was of their mother asleep on the lion rug. Curled almost like a kitten, one leg stretched out, the other tucked in. She lay on her side, and the cheek not covered by her hair rested close to but not exactly on the lion’s paw. Her cheek was mottled and only slightly gray. Courtney came in to tell her that nothing Mrs. Hoving said on the ride home from school made sense yet and it had been a whole week of speaking French in the car and it still didn’t mean anything beyond bonjour and je t’aime. Her mother’s sundress was lifted all the way to her waist as if to cool her legs off. Bonjour, Maman. Je t’aime. Her favorite bathing suit, the black one, was loose around the tops of her thighs. Je t’aime, Maman. Her mother was being too careful lately with her diet.

Thirty-three years old is awfully young to have a tricky heart, said one of the women in the den. My goodness.

It wasn’t quite so simple, said Ruth and then whispered her motto about small ears and big mouths. They could all see Courtney at the kitchen counter.

Looking for the oranges, dear? called out Ruth like she was the darling wife and mother in a black-and-white movie. So many people liked her for what she was doing. The neighborhood women who sat with her, drinking gin and tonics, admired her and said so. You’re a trooper, Ruth.

They’d never seen her in the days when she wasn’t a trooper at all. Ruth at the Beach Club snack bar, dipping the French fry basket into bubbling oil. Then she was Mrs. Carter, and one day she had a chevron-shape burn like a red arrow stuck on her forearm. Hard not to get hurt in such tight quarters.

She’s blind and foolish just like me, their mother said. It was a hot day and her temper got the better of her. That’s how she explained it. Later when they were back over the fence, back on their own rocks, tiptoeing toward the back steps. The heebie-jeebies, the creeps.

It’s not that poor woman’s fault, their mother said.

The first summer on Honeysuckle Lane and the first without the Beach Club. In fact no ocean at all, which was strange. They were still quite close. But Ruth preferred a day camp for the girls, with itchy woodland hikes and swim practice in a scummy chlorine pool.

They were both older now than their mother had been on the day she returned to London from the safe countryside to find only the crater where her house had been. And when Ruth was being annoying, going through their dresser drawers, insisting on a particular order to their underwear, Paige would whisper to Courtney: At least she’s not as bad as the crater. Which was funny but not very.

When she was returned by train to London, with the other children, their mother was able to find an aunt to help her—really only a courtesy aunt, a neighbor named Florence Kinney. And their father liked to say how resourceful their mother was and, for a little girl, how very brave.

In the ocean house, down the hall from her bedroom, their mother made a kind of dressing room of a windowless storage closet. There, inside a cigar box, she kept the striped handkerchief she wore around her neck in case she needed it as a mask at the end of the war. In Hampstead the air was often filled with ash. And every single day, Florence Kinney would say it was all beyond her. The care of a child in this misery was completely outside her ken. Every other person had a crater, after all, but not everyone had an orphan thrust her way.

That’s why when their mother was very tired or had the heebie-jeebies or the creeps, their own father knelt beside her and put his arms around her legs, as if she were only a tiny girl, like them. In the house by the ocean everyone who needed a mother had one. This was their joke as a family. A surplus of mothers. Mrs. Hoving thought this was funny, too, because of course she was one of them. Their father held their mother tight around her knees until she laughed, saying: Off! you’re a nuisance, her fingers curled soft around his wrists.

In mid-August, everyone on Honeysuckle Lane was asked by the Long Branch township to stay home and indoors as much as possible while the authorities cleaned up the mess and the danger after the surprise hurricane. This came over the radio.

Though the rain itself lasted less than a day and a night, the rivers and creeks overflowed, taking bits and pieces from the waterfront inland. A dinghy landed as far as the lawn at the end of Honeysuckle Lane. And the Beach Club and all the towers went dark.

As soon as Ocean Avenue was passable, defying municipal orders, Ruth loaded the girls in the car for some fresh air and a little snooping. She’d had some news, she said. Through the grapevine. They’d go investigate if it was true.

The ocean house belonged to their father, of course—completely, irrevocably. But now the town—in a plot!—was considering some kind of eminent domain. All because the seawall had been breached for half an hour!

They were going to see this travesty in motion. The girls didn’t know what Ruth was talking about. But now they waited on the sodden salt-burned grass behind the cypress trees while Ruth spoke to a police officer who’d set up a table in their old seashell driveway. Firemen in high waders came by and drank water from Dixie cups then pulled masks down over their faces and went up the high white-painted back steps where the girls once liked to hang their bathing suits on the railing to dry.

Inside, said the policeman—a grouchy man with a wide flat nose—the water had made a mark, like a finger run all along the dining room wall. A grubby, little girl’s finger, he said to Paige. Someone who didn’t wash her hands before dinner.

That’s enough of you, said Ruth. But too late, they could see the slimy trail marking their mother’s Japanese silk wallpaper. Through the white herons and the reeds. About three feet high, said the policeman to Ruth. I swear it.

All a charade, said Ruth. I don’t believe a word. A finger mark on a dodgy wallpaper? And you’re taking a house? Every one of us will be out on our keesters at this rate.

A fireman slogged toward them. He lifted a Dixie cup in a soot-black hand. The house is deserted, he said and smiled down at Ruth in an ugly way. A way that Courtney recognized as pleasure. And felt a funny twitch of being glad for him. Glad for his happiness.

Nothing like it, said Ruth. Not for a minute.

The girls were marched back to the car, and Ruth made the sign—a zip on the lips—of not saying a thing about this adventure to their father.

Despite their silence, at dinner that night their father looked downcast. So he knew. Though he said it was just the weather. That and something about taxes and a faulty plan. A thieving accountant. No recourse. He was speaking in code, to Ruth only, but they could tell by her face the news was shocking and bad. There was a very long pause after he finished talking. Chewing was impossible. Courtney remembers this night after the hurricane, the feeling as if her jaw had been welded shut by all the electrons Ruth said were flooding the air.

Wait, Paige said, as if she’d figured the whole thing out. Maybe things would be much easier if Ruth could just have her wish.

And what’s that? asked their father.

They—she and Courtney—could be taken by someone else along with the ocean house for good. Save a lot of trouble all round, Paige said with the slightest fake British accent.

Their father studied Paige: her long straight brown hair, the feathery arch of her eyebrows, her mother’s mobile, easily happy mouth, grim now, serious. He studied Paige for a long time, as if in reappraisal, before he answered in the low quiet voice. The voice that told them they didn’t need to believe him at all. He said that someday they’d recognize the jewel they had in Ruth.

Right after the hurricane, Mrs. Hoving came to visit Ruth on the screen porch. The back lawn was covered in broken branches of still-green maple leaves. All the jetsam and debris half-swept into piles for the municipal trucks to remove one yard at a time.

Mrs. Hoving had been helping Mrs. Lanahan down the road. She still did a bit of piecework stitching on the side, drapes and so on. She could do light upholstery, too. If Ruth ever needed such help. And she was so nearby today she thought, Oh, let me just lay eyes on the little ones again. Her niece’s husband was delayed picking her up, and she said to herself and then to Ruth: I told myself to walk down the lane to where that kind man has made a new home. A new start. But was it true?

Mrs. Lanahan had been full of news about the ocean house. Mrs. Hoving couldn’t believe her ears. Condemned?

Courtney came home from school but not Paige. All Mrs. Hoving had time to do in front of Ruth’s frowning, scouring eyes was pat Courtney’s wrist and say, You always had your mother’s pretty hands. Then her niece’s husband pulled all the way into the circle drive in a loud Oldsmobile with a discolored bumper. Mrs. Hoving went right out the front door. Just like that, Queen of Sheba, said Ruth to their father that night and imitated a wide sashay that looked nothing like Mrs. Hoving’s aching hip or her careful steps.

Did Mrs. Hoving leave a message for me? asked Paige.

She talked about Mama’s hands, said Courtney. Probably that was for you, too.

The main thing she said was that she was grateful, said Ruth, yes, very thankful that you two were so well loved now. At long last.

That sounds like a fib, said Paige.

Apologize, said their father.

Paige scraped out her chair and darted out of the dining room and up the staircase. Upstairs, the door to their room slammed shut.

Courtney kept her face averted from Ruth and waited for her father to make sense of the situation. He seemed confused. As if Mrs. Hoving had moved something important or stolen something and left the door wide open to worse. Finally he said, Eat your dinner, now, Courtney. It will only get cold.

It’s too gross, she said quietly. But he was distracted, listening, as if he could still discern Paige through the ceiling. I want to puke? whispered Courtney, as if telling her father what he really was listening for. Though he didn’t know it yet. Spoiling a surprise.

Oh, for the love of god, said Ruth. That’s it! That’s it. And she, too, scraped back her chair and let the tears in her eyes show before rushing out, hugging her belly, looking to Courtney like a troll who’d swallowed a poisoned frog.

Everyone’s so upset, said Courtney with a smile to her father.

Maybe Mrs. Hoving should mind her own business, he said and went off to comfort Ruth.

The night before, Ruth told them that the hurricane had flooded the Olympic-size pool at the Beach Club, so much that waves formed and pushed the French fry cooker out of the boardwalk snack shack and onto the jetty. Only the benches on the boardwalk bolted in place had any chance of staying still, she said, but then the boards buckled up like a wave themselves and the benches went with them. Those that were commemorated—for Mrs. Lawrence Thees and for Miss Ethel Bolmeyer—were retrieved and being repaired first. Their mother didn’t have a bench. Which seemed right, since she had a whole house to be remembered by. But the pool rising up was a frightening idea. What if the waves had come high when their mother taught them to swim? She’d hold them tight and leap into the pool and help them flutter up to the surface and find their breath. The two of them so tiny and so strong their mother swam them around and around in her arms until they learned to kick free.

Hurricane or not, the new school year began just after Labor Day. Courtney was in sixth grade now, Paige in the fifth. To get to Star of the Sea they had to climb over and around the storm debris, downed tree limbs still uncollected, some shellacked in a dried greenish sludge. Seaweed.

Red tide, warned Ruth. Don’t touch anything.

Now, each morning before she left for school, Courtney arranged her seashells in a straight line, one touching the next, on top of her white dresser. Before she went to sleep at night, she shaped them in the circle. Bon matin, Maman. Bonne nuit. Je t’aime.

The first Friday back at school, she came home and the shells were gone and she knew exactly what had happened. Just to make sure, she stood in the archway to the den. Cocktails and hors d’oeuvres on a tray, Ruth in the middle of a story about Mrs. Hoving. Ruth paused and waited.

I’m cleaning my room, Courtney said.

Ruth sputtered a laugh. Oh, right. But one of the others, a more experienced mother, said, How nice!

But I can’t find my seashells. For dusting.

The two women sitting on the tweed sofa smiled. And Ruth caught her cue. Try the bookshelf over your desk? I’ll bet that’s where they are.

Thank you, said Courtney and went out through the garage to find Paige in the orchard. Paige had told Courtney she was strictly forbidden in the orchard, even in the mornings. No one wanted her in the orchard now. But Paige had taken her best things to give away. Just like she’d taken their father’s canon-style cigarette lighter and his English beer.

In the orchard, Paige stood against the outhouse, arms crossed and angry, as Courtney walked toward her along the path. Two boys, Eddie, with the bluish swollen girl’s mouth, and Henry, with the pink cheeks, sat on the ground smoking small black cigars. They looked up at Courtney, frowning. The third boy was Andrew Kennedy, leaning back against his tipped-over bike wheel, legs splayed. He didn’t look at her at all.

Out, said Paige. Now.

We are out, said Courtney jutting her chin. She stared at her sister’s tiny breasts on display, her uniform jumper on the ground. Her Carter’s underpants looked stretched out and baggy as if she’d carried things in them. The lighter, the shells. She still wore her school blouse, opened up, but the collar was smudged as if Henry’s black cigar and Eddie’s blue lips had leaked together there. Her tiny breasts, unlike Courtney’s, poked straight out like thumb tips. And the nipples were light small orangey caps on each. Courtney’s new breasts were rounder. Ruth junior, Paige had said in a fight, and Courtney worried this might be true. Her nipples looked like stupid pink toy pig pennies. Go away, said Paige. Last warning.

Ruth wants you, Courtney said.

What for?

How should I know? She told me to find you. She said even if you had to stay for detention, tell Sister to let you come home.

Henry stubbed out the black cigar. He stood and popped it through the half-moon slit in the door behind Paige’s head. As if she’d disappeared. He didn’t need to acknowledge her anymore. She’d failed at something, Courtney knew, and felt a tickle of panic for her sister. Henry’s pants were unzipped, but now he fastened them, slid his belt through the loops in slow motion. Buckle, jacket pulled on, his clip-on school tie shoved down into a side pocket. Yeah, he said to the boys. Eddie jerked up his book bag. Andrew Kennedy righted his bike. The three of them zigzagged away through the wrecked trees.

Nice work, Courtney. Paige pulled her uniform jumper on over her head.

Zipper, said Courtney.

Paige smoothed her flyaway hair. They’ll tell everyone, you know.

I’ll take my shells back now, said Courtney.

Tough luck, detective, said Paige. Too late.

The next week, the second week of sixth grade, Courtney’s new teacher, Sister Frances, said they were old enough to know the ins and outs of hell. They weren’t babies anymore. They had power. They could pray for those already in hell and for those who were well on the way, stumbling blindly along the dark path.

Paige. Obviously. She’d let boys rummage around in her underpants.

Sister Frances then prompted the prayer for those who had sinned against us. This was the merciful part, the intervention for our enemies. This was all fascinating and not something their mother had agreed with, ever. She had suspended her belief when she was little, she told them, like a balloon. Like a zeppelin! And she seemed to think this was very funny. So Courtney hovered now between whether to try this prayerful intervention for her sister or not. But then she did. She imagined lifting Paige out of her quick certain slide into hell at the last minute, throwing a damp towel over Paige’s scorched wispy leaf-tangled hair. She prayed and nothing changed. So on Thursday afternoon Courtney tried her mother again. She hid her mother’s play earring, a pearly cluster on a rusty clip, under the bed skirt. She had a candle stub from the kitchen drawer. She nestled the stub in the shag carpet and lit it. The instant the bed skirt caught fire Ruth was banging on the door.

Something about the look of Paige, her legs wide, knee socks high, oxfords laced, backbone lined up at the sagging corner of the old outhouse, hair a nest with dead leaves tangled at the top of her head, underpants hanging in heavy folds, her nipples, her nylon school blouse reminded Courtney of a painting her mother had kept hanging on the wall of her dressing room. Nymphs, water nymphs, bored and dozy-eyed like Paige with bodies that looked electric under the winding fabric mostly on their hips. The nymphs dragged toes through shallow ponds. They sat on rocks or propped their bodies against tree trunks like Paige at the outhouse. Courtney could kill Paige. Just kill her. Paige’s underpants all baggy around her legs just like their mother’s bathing suit because their mother had become too thin.

Even though their father had tried to fatten her up with barbecued steaks on the grill, salt in the air, blood rolling on their plates. Their mother would lick and chew. Hurry now, said Mrs. Hoving standing at the back door. Come girls. The light still pink over the ocean, Mrs. Hoving tucked them into bed. Then their parents would come and find the exact place on each forehead to efficiently deliver their love. Their father had forgotten all about that. No one was delivering anything anymore. But Paige in the orchard with her baggy pants was transmitting something to the boys on the ground and they were the ones with precision now. Courtney hated her sister for deserting her this way. She truly hated her. And that made her feel very sick in her stomach.

Downstairs in the kitchen, waiting for her father to come home and adjudicate the bed fire, her mother’s pearly play earring sitting on a dish like poison, Courtney slumped and still—not a word now, hissed Ruth, not a sound—two things occurred to Courtney. The first thing was that Ruth had knocked before charging in, which she seldom did, and the second was that she must have been right outside the door the whole time, waiting for Courtney to do something bad.

Ruth stood now whisking rye bread crumbs into gravy at the stove top. Potatoes roasting in the oven. A soft, soothing pop-pop of gunfire from the den, where Paige, home from school, watched television. When their father came in at dinnertime, Ruth would then wash her hands of Courtney and her obstinate refusal to accept the love and nurturance so abundantly provided. She was finished being treated like the servant, she said, stirring the gravy, rehearsing. This was it.

But their father was in no mood for Courtney. Right away he tried to shoo her into the den with Paige. You stay where you are! said Ruth.

Listen, he needed to talk to Ruth, now, because he wasn’t going to let the bastards win.

Of course he wasn’t, said Ruth, but she squinted when he put his briefcase down on the chair beside Courtney. He might let the bastards win, her look said. He just might.

And it occurred to Courtney that Ruth washing her hands of all of them might be the answer her mother was giving to the prayer. Her mother would never do anything to hurt Paige, Courtney now understood, even if she did have to go to hell. Their mother had protected Paige against the boy ghost and the ocean. Like their mother, they only swam in the pool. And one time she’d found Paige in the dark rock cellar: I see you, darling. Come out now. She’d been missing for so long, their father had given up and feared the worst. Courtney had forgotten about all that.

Don’t move, Ruth said. Don’t move a muscle.

But to her father, Courtney had become invisible. The corrupt thieving assholes on the town council, the bastards at the Beach Club. He turned blood red. Courtney knew how this might unfold. Sometimes their mother had hidden them in the ocean house, hidden herself. But Ruth was too stupid and the house too small for really hiding. Courtney slithered down lower in her chair as a warning, staring at Ruth until finally she got the hint and relented. I’ll call you girls in a bit. Out! Out! Right this instant.

Turn it up, Courtney said in the den. Quick.

You, said Paige. But when the voices got louder in the kitchen, she threw Courtney the remote.

They lay low together on the sofa. On the television, a triple homicide and not a single suspect so far. The detectives were stumped. Courtney couldn’t follow the story.

Of the three boys still left in the orchard, the ones who hadn’t graduated last year, Courtney preferred the youngest, Eddie, with the leaky-blue-pen girlish lips. He was in the other sixth-grade class. On the playground, if she kept very still she could feel him watching her from within the clump of boys who shuffled around under the basketball hoop. The dark head of probably Eddie turned slightly toward her. She could feel it. Like an arrow. A dart.

She asked Paige, casually, through the veil of the loud TV, she was just wondering, if Eddie had ever said much about her.

About who? asked Paige, her head turning sideways, ready, for once, to give a straight answer. Who do you mean?

Courtney waited a moment. Paige was teasing her. Then she realized, no, she wasn’t. She hadn’t heard her. Well, I mean, does he mention Fiona Murphy? asked Courtney.

Not a prayer, snorted Paige. Good one.

In a little while, Ruth appeared in the door then closed it behind her. Turn that down, will you?

Courtney pushed the mute.

Set up the TV trays and I’ll bring in sandwiches. She was talking to them as if they were all at the Beach Club. And they were just another pair of snotty kids waiting for their fries.

The following Monday, Mr. Kemp from the orchard called Ruth on the telephone with terrible, shocking news about Paige. News that Ruth could scarcely believe much less repeat. Now Paige was the one sitting at the kitchen table waiting for justice. And Courtney was curled up on the sofa in the den still in her school uniform, eyes half-closed, watching a western. The long ruffled dresses on the saloon girls, the spark in their attitude, smiling for the deputy, who was a dunce, and longing for the sheriff, who was not. Bang, bang, bang, the crooked guys were run out of town. Most of them near dead. Now Paige was listening to Ruth’s threats, rehearsing what their father would say when he knew what she’d been doing in Mr. Kemp’s good clean orchard. People eat those apples!

Ruth was bug-eyed with excitement. And something in her enthusiasm, the lush happiness of it, made Courtney feel that she’d told on Paige herself. Maybe she had. For so long later she would still feel the mistake in her heart, as if she had carried a mean little boy there, someone who would take aim at Paige and harm her, hope for the worst. Over and over and over until she was dead.

During the commercial, Courtney made a casual trip to the kitchen for some milk. But Paige wouldn’t meet her eye. Outside in the yard, the holly bushes caught the first pink rays before the sunset. The phone rang, and their father’s voice spilled out of the receiver held close to Ruth’s ear.

Right away, Ruth said.

She punched the receiver back on the wall, rummaged in her purse for the car keys, and headed for the garage. Now Paige caught Courtney’s eye. Ruth? called Courtney.

What now? said Ruth. She looked frantic.

Should we come with you? You don’t want Paige out of your sight, remember?

Oh, Christ in heaven!

Should we get in the car?

Come, she said. Come on. Hurry up!

So many important-looking black cars already lined up along Ocean Avenue it looked like a funeral. A whole gang of policemen lounged at the gate of the ocean house between the cypress trees. Ruth knew her rights, she said, but the police did not agree. Besides, who were the little girls? This was no place for children. Someone might get hurt. Already the bulldozers were aimed at the turret side of the house.

This is illegal, said Ruth, which made the policemen smile.

Such an enormous house and it took no time to come tumbling down. The rot through and through, said a fireman later, smoking a cigar, stale and sour by the smell of it. He’d taken it upon himself to guard Ruth and the girls from harm. In the end they were allowed to stand just inside the old gate once Ruth had convinced them that the girls were the rightful owners. It was their mother’s house, she said. And there was a sheepish squint of recognition in the fireman as he looked first at Paige then less certainly at Courtney. All right, he said.

Then a fireman with black hair swirling on his forearms came over and explained the methodology to Ruth. Turning his face close to the cypress and out of the wind. Basically I could have knocked it over with my fist, he said. So we didn’t need a lot of fancy machinery. Before the sky was fully dark the house lay tucked inside its foundation.

Ruth had some old red cocktail napkins stuffed into her capri pant pockets. Here, she said to the girls, gesturing to their noses, and she did the same herself. The wind off the ocean had shifted and caught up the debris dust from the house like spray and a contaminated wet breeze now prickled their skin.

Oh, you know what? said Paige. I forgot to tell you, her eyes serious over the mask of the red cocktail napkin. Eddie asked me to give you a message.

Courtney looked at her.

He said to tell you, no offense, but you stink like dog farts.

Courtney looked back to the jetty. Completely visible now where the house had once been. So surprising how small and crumbling it was without the house to protect it.

That was the last of the ocean house, a collapse of rubble in a deep pit, doused by spray coming across the rocks. For good measure the firemen directed their hoses toward any flighty timber. Whatever might be caught up by wind or vandalized was soaked until useless.

Someone said, You’d think they’d want to save those precious windows.

But Ruth shook her head. You start parsing this and that and you’re never done.

Does Ruth hate the house? Courtney asked Paige. It’s not that, Paige said. It’s you. She told Daddy you were the worm in their happy cabbage. She said it’s a shame you’re not more like me.

You? said Courtney. You? People can just rummage around your underpants whenever they feel like it. This was a lame insult and Courtney tried to think of something better.

But there were shouts and the dousing firemen dropped their hoses and scampered back from the pit just as a leap of flame shot up from the center and died right down, a bit of gas trapped in the line flaring, that’s all, but Paige burst out crying. She was suddenly sobbing and couldn’t be calmed. They left then, and Ruth put her to bed with an aspirin and a cool towel for her eyes.

Courtney, you bunk in the den tonight, Ruth said. And all night long the tweed nubs of the couch stung at Courtney’s cheeks like the flying debris.

Paige didn’t recover right away. And the second night of the fever, Courtney went upstairs and found Paige out of the sheets, her nightgown flung up and her legs sprawled. At first Courtney was stunned and then she argued in her mind like a prayer to go forward to help Paige. And her feet obeyed. She touched Paige’s arm, which was hot as a dish from the oven. Does it hurt? she asked, and Paige moaned and said no. I’m just burning up. I caught fire.

No, you didn’t, said Courtney. You couldn’t. We were standing too far away.

I was supposed to, said Paige. And I did.

I think it’s only supposed to happen for a short time, then stop.

On the third night, Ruth said, Fever or not, it’s time to rejoin the living. And when their father came home it was like the girls were watching a beautiful show. It had nothing to do with them. Paige, pale and sulky in her green pajamas, at the dinner table. Their father was telling Ruth the big news from the courthouse. The town council. His lawyers had finally severed the witch’s head.

What head? asked Courtney.

Her father couldn’t hear her. That conniving bitch, he said to Ruth. She thought she’d just go on strangling me from hell.

Who?

Sweetheart? their father said to Ruth. Pausing like the sheriff, finally about to choose the right saloon girl, the most virtuous. Sweetheart, they dropped the charges.

Ruth put her hands together and closed her eyes.

What charges? asked Courtney.

And.

And?

He’d been offered a variance to build a tower.

Ruth burst out laughing. No!

Yes.

Now won’t those Beach Club pokey-pokes be singing a different tune.

Pokey-pokes? asked their father, delighted. That’s cute.

Each apartment in their father’s new tower had a balcony with hurricane-resistant glass. This was a big point in the design. So the inhabitants, forty families on the ocean side, could sit in the comfort of their living rooms and not be looking at a steel barricade. They were paying for the view after all. The hurricane glass in standard green was nearly an inch thick and cost one hundred dollars a square foot and would weather any storm. How had the crab-claw etchings and the pale-pink glass roses survived all those years?

The ocean house had been built on rocks, on sand, but the tower required an excavation so deep, so reinforced, it would double as a bomb shelter for the families during the Cold War. Each apartment had access to impermeable individual kiosks like concrete cages with slats in the wall for bunk beds. Most of the families kept junk there, stuff they couldn’t fit in the apartment. The oxygen tanks hanging at intervals lost pressure over the years. And despite claims, water seeped in and pooled. When Courtney was fifteen, she led Eddie through the sub-basements as dark and shadowy as the catacombs where the Christian martyrs hid or just waited for death, and she felt the warm silky nub of his bluish penis for the first time there. Her sneakers getting wet. He pushed up hard against her until his heart beat inside the cage of her own chest like love.