Читать книгу Curlew Moon - Mary Colwell - Страница 7

WHAT IS A CURLEW?

ОглавлениеThere is a wildlife spectacle that can transport the soul to a place of yearning and beauty, to an experience that has inspired generations of thinkers and dreamers. Imagine, if you will, a blustery cold day in December. Bitterly cold. A bird stands alone on the edge of a mudflat, some distance from where you are standing. Its silhouette is unmistakable. A plump body sits atop stilty legs. The long neck arcs into a small head, which tapers further into an extended, curved bill. The smooth, convex outlines of this curlew are alluring. They touch some ancestral attraction we all have for shapes that are round and sleek. The curved curlew’s outline is anomalous in this planar landscape, but its colour blends well. The mud is gunmetal grey, the bird brown and the water murky. The sky is dull with a hint of drab. The air is tangy with the smells of decay.

Occasionally the bird wanders a short distance and probes the mud with its beak, sometimes digging it in and twisting it around a little. Every now and then it pulls something clear of the surface, throws back its head and swallows. It is most likely a worm or shellfish, which is consumed without a fight. There is no showiness or drama, no prey is torn apart with dagger-like talons or razor beaks, it is just take a step, probe, suck; take a step, probe, eat – and repeat. It is absorbing to watch in its rhythmic motions. Icy gusts tease the bird’s feathers; at times, the curlew looks like it might be blown off its thin legs, but walk on it does, interrogating the mud beneath its feet.

Observing this self-reliant being in the distance can feel like an act of endurance. The wind is coming straight off the sea, cold and peevish. It finds every buttonhole and cuff, intent on extracting warmth. On this raw day, standing still is not pleasant. It is tempting to move closer, but despite all our inventiveness we have nothing that negotiates deep, cloying mud. Certainly not boots. Besides, curlews are nervous. If you cross an invisible line a few hundred metres away they will take off, crying in alarm. Best to stay in one spot, pressed to the binoculars, and tough it out. In the distance, the water stretches away and merges with the sky – grey into grey. The curlew is safe from unwanted encroachments in this shifting, liminal world.

Besides the admiration that you feel that something so insubstantial can withstand the rigours of this unforgiving landscape, you may not be particularly awe-inspired. You might decide it is time to get back in the car and go home, but stay with it – something magical is about to happen.

Alan McClure, in the first verse of ‘Schrödinger’s Curlew’, asks the same question. Why keep on watching the curlew visible through his window?

On the face of it, there isn’t much about this bird

To stop me in my tracks.

Brown, oblivious, busy with the ground

It totters along on stilted legs

Probing among the frozen fields.1

He does keep watching, though, and so will we. There is no sound, apart from the wind over mudflats. Wilderness has its own quality of silence, an ancient, unchanging quiet. And suddenly, for no obvious reason, the curlew takes flight. Its long legs and pointed wings launch it into the air. It soars along the horizon. Its outline resembles a miniature Concorde, purposeful and strong. But it is not the sight that is astonishing, it is the sound. The air is cleaved by a piercing, soul-aching cry – ‘curlee, curlee’ – that spreads over land and water. It is at once sweet and painful to hear, following Norman MacCaig’s description in his poem, ‘Curlew’:

Music as desolate, as beautiful

as your loved places,

mountainy marshes and glistening mudflats

by the stealthy sea.2

The pauses between the calls are as poignant as the cries themselves; they define the silence and fill it with expectation and emotion. Given a religious turn of mind, you could almost describe it as a benediction. It is as though the winterscape has been blessed.

‘Schrödinger’s Curlew’ also ends with an epiphany:

And then, untouched by my musings

The bird spreads its wings and lifts,

Naming itself, with a long, pure note

And my heart, in two states,

Leaps

and breaks.3

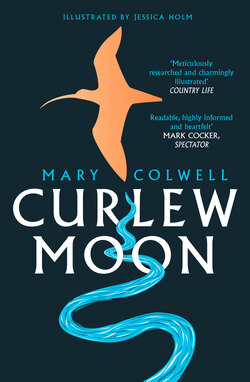

If you haven’t done so before, you have now met the bird named after a sliver of the moon and the taut curve of an archer’s bow, Numenius arquata, an everyday sprite, otherwise known as the Eurasian Curlew. At once magical and down-to-earth, this bird is a mysterious prober of dung and earth, mud and meadow.

Both parts of its name – Numenius and arquata – refer to its most conspicuous, long curved bill. Numenius is the Latinised version of two Greek words, neos for new and mene for moon, that thin shaving of light that is full of potential. Arquata is Latin for the archer’s bow; taut and stretched into a smooth arc. Numenius arquata, then, is the new-moon, bow-beaked bird.

Eurasian Curlews are Europe’s largest wading bird. The body is about the size of a mallard duck, but with much longer legs to hold it clear of the water. The small head, supported by a stretchy neck, terminates in that astonishing sickle-shaped bill. They are predominantly brown and grey, but when in flight, the white rump and underside flash against the sky. Eurasian Curlews are found across the European continent, from the west of Ireland through to Siberia; there are thought to be around one million birds in all, but that is only a best guess. Many areas they occupy are remote and difficult to access, so we know surprisingly little about this common European bird.

In the winter, curlews are distributed widely along the coastlines of northwest Europe, the Mediterranean, Africa, the Middle East, India and Southeast Asia. They form large flocks that can be thousands strong, feeding and roosting together. In the UK, winter numbers of curlews swell to 150,000, boosted by the arrival of northern European birds, their own homes having become too frozen for these probers of mud. We are truly fortunate, one might say honoured, to have so many marvels around our shores to lift the winter months. They mingle with our own native birds that stay all year round. That figure is put at an overly optimistic 66,000 pairs. Curlews that breed in the north of England and Scotland tend to winter around northern estuaries like the Dee or Moray Firth. Southern-breeding birds go to The Wash in East Anglia, the Severn estuary and to the rocky shores and inlets of southwest England, Wales and Ireland. Some go further, to the warmth of southern Europe.

Come early spring, the coast empties as the European birds go back to the continent and the British and Irish ones head inland to breed on moors, peat bogs, rough pasture, damp, lowland flower-rich meadows and even silage fields. In simple scrapes on the ground, they lay three or four olive-green and brown mottled eggs, which the parents take turns to incubate. As Britain and Ireland are home to 25 per cent of breeding Eurasian Curlews, these islands are vitally important for their future.

Spending time watching curlews, whatever the season, is to observe a spectacle, but not in an arresting, adrenaline-pumping way. It is more of an inner experience, at the level of the soul, where the ordinary and everyday becomes extraordinary. And it is as much an experience of sound as of vision, of mind and heart.

That long bill is the most recognisable feature. It is unmissable. Three times the length of the head, up to 15 centimetres long in females, though slightly shorter in males, and curving gently downwards. It is both elegant and surprising. The pleasing arc removes from it any association with daggers and spikes; it is unthreatening, sculptural even. Psychologists tell us that roundness and smoothness trigger associations with health and youthfulness, like strong muscle against taut skin. A curlew’s bill is something that you might like to hold and run your fingers over.

The curve is there for a reason. With this arcuate tool, curlews can probe deep into sediment and explore the complex tunnels and pathways made by buried worms and shellfish far more easily than a straight bill would allow. Straight-billed wading birds, like godwits and oystercatchers, rapidly jab into the sediment and take their prey by surprise. Curlews do it differently; they plunge deep and use the bulbous, sensitive tip to feel around. The nerve-filled end of the bill opens independently, the tips acting like a pair of remote-controlled tweezers. This is made possible by joints in the skull which can push the upper bill forwards so that it can act alone. With its finger-tip sensitivity it is remarkably good at detecting deeply buried food. It is also ideal for poking around in the surface nooks and crannies of a rocky shore. The length allows access to food out of reach to those less endowed in the bill department.

Curves have their disadvantages, though. Structurally, they are weaker than straight bills and have to be strengthened by internal struts and thickenings. The reinforcements narrow the internal passage so that a curlew’s tongue can’t reach down to the tip to help extract and swallow buried food. It has to withdraw its bill and then move the food to the tongue by jerking its head. Big prey, such as crabs, are winkled from their hiding places and tossed around, often violently, before being swallowed. You can see curlews shaking them so hard their legs fall off (the crab’s legs, not the curlew’s) before they are moved to the top of the bill and down the gullet.

The prominence of the bill has, inevitably, set our imaginations whirring. In some areas, a local name for curlews is whaup, partly referring to the sound of one of its calls, but also because it evoked folk memories of those half-human, malevolent little people that plagued generations gone by. A whaup was an evil, long-nosed, thin-necked goblin that ran around the roofs of houses at night. They were notoriously mischievous and spread rumours and bad luck. ‘A whaup in the nest’ refers to some brewing unpleasantness, or the hatching of evil plans. A Scottish Highlander’s prayer asks to be protected from ‘witches, warlocks and long-nebbed (nosed) things’. The curlew became synonymous with these negative notions and in some places it became a bird to be feared. A long bill, finely tuned by evolution for feeding in muddy environments, must also, it seems, give rise to unfortunate connections with our complex, cultural world.

A curlew’s bill may be the feature that catches our eye, but when it opens and starts broadcasting, it is the sound that captures our soul. The experience of hearing the call of the curlew is, for me, akin to what C.S. Lewis described as being ‘surprised by joy’. For Lewis, joy is not merely happiness, it is far deeper and unfathomable. He describes it as an unexpected, centuries-old upwelling of longing and desire that has somehow always been there but has remained unnamed. It is usually fleeting, overwhelming, always complicated, always layered. It has associations with memories that we can never quite define. ‘All Joy reminds,’ says Lewis. ‘It is never a possession, always a desire for something longer ago or further away or still ‘about to be.’4 The late Terry Pratchett, in A Hat Full of Sky, had an earthier turn of phrase: ‘Joy is to fun what the deep sea is to a puddle. A feeling inside that can hardly be contained.’ This is the surprising joy evoked by the varied calls of the curlew, whether it is the bubbling mating song tumbling in cadences from a summer sky, or the simpler, arrowed sound of its name, firing across the reaches of a mudflat in winter. Pure, unmitigated joy.

Curlews are highly vocal and have something to say in most situations. Their calls range from harsh barking and yelping to growling and soft, low whistles – and much else in between. They have specific sounds to communicate with developing chicks inside the egg, to call their mate to warn of danger, to scare away predators and to mark their territory. The signature call, the one from which the bird gets its name, is coorli or curlee, which is often heard as the bird takes flight over moorland and estuary. ‘Lancing their voices/through the skin of this light’,5 as Ted Hughes described this soul-aching cry that lingers in the air long after the bird has flown. If you imagine the shape of the call as a word, it is also curved. The ending of curlee rises in tone, similar to the pen-stroke flourish of a flamboyant scribe. Both the call of the curlew and its bill are curlicued.

But perhaps the most haunting song is a melody that can lighten even the most desolate of days – the bubbling call, most often heard in the breeding season. It is a gradually building trail of notes that rises up through the scale, sounding louder and ever more urgent as the bird flies skywards. As the call ends, the curlew then swoops through the air on stiffened wings. One anonymous poet described it as:

A crescendo of

sound bubbles

bursting in cadences

of liquid joy.

The cry bursts forth from the bird’s lungs through its binary voice box – two tubes that work in harmony to produce a richness of tone that intertwines both the major and minor keys, confusing our emotions. The bubbling call is ecstatic, both full of life but with deeply melancholic undertones. ‘Such trifling themes as life and death are kept in Curlew’s calls …’ wrote A.W. Bullen in his poem ‘Curlews’. ‘If my voice could be anything like theirs … if only … I would swallow my share of lugworms to know their truths …’

Lord Edward Grey, ornithologist and politician, found a sense of calm and hope in the music of the new moon bird:

Of all bird songs or sounds known to me there is none that I would prefer than the spring notes of the Curlew … The notes do not sound passionate, they suggest peace, rest, healing joy, an assurance of happiness past, present and to come. To listen to Curlews on a bright, clear April day, with the fullness of spring still in anticipation, is one of the best experiences that a lover of birds can have.6

For many, to hear a curlew is to listen to the wild. It is music that crystallises the range of emotions that well to the surface when standing on a lonely moor or walking through a spring meadow. Like adding seasoning to a dish, their calls add highlights or depth to the landscape. You might hear the ‘sweet crystalline cry’ recorded by W.B. Yeats, or perhaps the more melancholic ‘lingering, threadbare cry’ noted by another Irish poet, Thomas Kinsella. Alfred, Lord Tennyson only heard bleakness and described calling curlews as ‘Dreary gleams about the moorland flying over Locksley Hall.’ You may, though, feel happiness and hear Ted Hughes’ ‘wobbling water-call’ and smile.

Curlews are shape-shifting sprites that tease and tangle our emotions. Their evocative cries are aural keys that unlock our secret thoughts, and have inspired poets, artists, writers and musicians from time immemorial – and still do. This is perhaps all the more remarkable, given that their appearance is relatively unprepossessing. Looking past their beak, their colouring is less than striking. From a distance, they may even seem a little dowdy. But as with many works of art, the true beauty is discovered in the detail. At close quarters, the intricate patterning of brown, grey and cream feathers is exquisite, shimmering with the rippling tide or merging into the bright colours of a flower-filled meadow. Rain, cloud or sun bestow different characteristics. But to see the loveliness in curlews requires more than a passing glance.

G.K. Chesterton understood that what can appear dull on the surface often belies a shifting palette. When challenged about the drabness of grey as a colour, he asks us to consider an English village on a dull day. To some it may seem boring, but watch a while and it is a wealth of charm. ‘Clouds and colours of every varied dawn and eve are perpetually touching it and turning it from clay to gold, or from gold to ivory … The little hamlets of the warm grey stone have a geniality which is not achieved by all the artistic scarlet of the suburbs.’ This can only be seen by taking enough time to absorb the ever-changing delights. So too with curlews; to watch them in rain or sunshine, at dawn or dusk, is to see a restless beauty adorning a muddy marsh.

While many creative juices have flowed at the sight and sound of curlews, many gastric ones have, too. Being the UK’s largest wading bird, they have provided flesh for the pot for centuries. It is illegal to hunt them now, but before they were protected by the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981, it was said that the best time of year to eat them was soon after the breeding season. Weeks of feeding on insects and berries was thought to make their flesh sweet. According to one old Cornish recipe, this was the ideal time to make curlew pie, which required mincing up two birds with onions. Eaten later in the year, warned the chef, their flesh would be rank with the flavour of mud and shellfish, and will need more herbs to disguise the taste.

Winston Graham, the writer of the Poldark series, also refers to curlew pie being served in a pub in his novel The Loving Cup: A Novel of Cornwall 1813–1815. A seventeenth-century Lincolnshire proverb puts a price on them, and they weren’t cheap: ‘Be she lean or be she fat, a curlew has twelve pence on her back.’ Some versions change lean and fat to white or black, as it was thought the plumage of curlews darkens in the summer, though I have never found other references to this.

In Feast Day Cookbook, written by Katherine Burton and Helmut Ripperger, published in 1951, a Christmas Day pie extravaganza is described from the days of old, but no exact date is specified:

It is said to have contained, besides the crust, the following: four geese, three rabbits, four wild ducks, two woodcocks, six snipe, four partridges, two curlews, six pigeons, seven blackbirds; and it was served on a cart built especially to hold it!

The narrator of the medieval narrative poem ‘Piers Plowman’, written by William Langland at the end of the fourteenth century, says of the curlew that it is ‘a bird whose flesh is the finest’. Curlews also put in an appearance in The Forme of Cury, one of the oldest-known manuscripts on the art of cooking in the English language. It is believed to have been written in the late fourteenth century by the head chefs of Richard II (1377–99). It is a scroll made of calfskin containing 196 recipes. The word ‘cury’ is the Middle English word for ‘cookery’, and the recipes are full of exotic spices, Mediterranean delicacies and creatures we would not dream of serving today, such as whales, seals, porpoises and cranes.

By the fifteenth century, public feasts had taken on monstrous proportions, and curlews were part of the steamed, roasted and boiled menagerie that were used to display social standing. This is an account of the feast for 2,500 people made to celebrate the enthronement of George Neville as Archbishop of York in 1465:

They consumed 4000 pigeons and 4000 crays, 2000 chickens, 204 cranes, 104 peacocks, 100 dozen quails, 400 swans, 400 herons, 113 oxen, 6 wild bulls, 608 pikes and bream, 12 porpoises and seals, 1000 sheep, 304 calves, 2000 pigs, 1000 capons, 400 plovers, 200 dozen of the birds called ‘rees’, 4000 mallards and teals, 204 kids, 204 bitterns, 200 pheasants, 500 partridges, 400 woodcocks, 100 curlews, 1000 egrets, over 500 stags, bucks and roes, 4000 cold and 1500 hot venison pies, 4000 dishes of jelly, 4000 baked tarts, 2000 hot custards with a proportionate quantity of bread, sugared delicacies and cakes. 300 tuns of ale were drunk, and 100 tuns of wine, a tun containing 252 gallons according to the usual reckoning.

According to The Booke of Goode Cookry Very Necessary for all such As Delight Therein (1584), the correct way to roast a curlew is to put its legs behind the body, cut off the wings and wind the neck so that the bill rests on the breast. Others suggest ‘letting the heads hang over the pot for show’.

In the seventeenth century, curlews baked in a pie, and also roasted, were served to King James I, and a few decades later, at the end of the century, they appear in a cookbook by Hannah Woolley, instructing servants in the correct terminology for ‘the curious art’ of carving different birds.

In cutting up small birds it is proper to say thigh them, as thigh that Woodcock, thigh that Pigeon: but as to others say, mince that Plover, wing that Quail, and wing that Partridge, allay that Pheasant, untach that Curlew, unjoint that Bittern, disfigure that Peacock, display that Crane, dismember that Heron, unbrace that Mallard, frust that Chicken, spoil that Hen, sawce that Capon, lift that Swan, reer that Goose, tire that Egg.

It is a testament to their former abundance that many a curlew will have come untached. In some areas, their eggs were also collected and served alongside the meat up until the middle of the twentieth century. Alas, that vision of a plethora of new moon birds gracing the land from the tip of Scotland to the moors of Cornwall, from Kerry to Norfolk, is a distant memory.

Over the last thirty years, numbers of curlews have declined on average by 20 per cent across the European continent, but that figure is misleading for the UK and Ireland, where losses are much higher. In their most western reaches in the Irish Republic there is nothing short of a disaster unfolding before our eyes. In the 1980s there were many thousands of pairs of nesting curlews, but today only around 120 remain. The official population for the UK is 66,000 breeding pairs, although my personal opinion is that this is optimistic and the real figure is much lower, maybe less than half that number. In Northern Ireland, for example, there has been a decline from 5,000 to 250 pairs since the 80s. The Welsh population has fallen by over 80 per cent and is now thought to be fewer than 400 breeding pairs. England and Scotland have lost around 60 per cent of breeding curlews in the last twenty years. So alarming are the figures that curlews were made a species of highest conservation concern in the UK in December 2015, and put onto the red list of threatened species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the worldwide union of conservation bodies that monitors the status of animals and plants throughout the globe. They are now in the same category as jaguars, ‘near threatened’, indicating that extinction is likely in the future.

The reasons for such dramatic declines across the board are many and varied. Farming methods, the spread of forestry, the drainage of uplands to create pasture for sheep and cows and predation of their eggs and chicks have all taken their toll, but despite the great losses not everyone has noticed they are disappearing. Curlews suffer from a problem specific to them: a distortion of our perception. The winter curlew population of 150,000, boosted by birds from Scandinavia and Finland, means that between September and February large congregations of curlews can be seen around the coast. The arrival of these continental birds gives the impression of curlew-abundance and that all is well. Come early spring, however, when the large flocks disperse, many fly back to northern Europe to breed, leaving our residents scattered increasingly thinly across Ireland and the UK.

There is no escaping the fact that curlews are failing to thrive and breed in the UK and Ireland. Year after year their numbers fall, and few of those that remain are managing to breed successfully in an increasingly hostile landscape. With precious few youngsters surviving to take the place of the older birds, the trajectory is resolutely downhill.

The transition of curlews to high conservation status in December 2015 was the trigger for me to follow them more closely. It was then that the idea of a 500-mile journey on foot began to crystallise and became a concrete plan. This would be no aimless wander but a pilgrimage, an inner and outer journey that has a goal. It would follow a definite line across the countries at the far western edge of the range of the Eurasian Curlew, a path that, as far as I could discern, was unique. Walking was by far the best way for me to track these increasingly elusive birds; it allows time to connect with the landscape and feel its character, something that cannot be achieved in a car. I would start in the early spring when birds were first arriving on their breeding grounds in the west of Ireland, then continue through the heart of Ireland to Dublin. I would then sail to Wales, arriving as incubation was well under way. After travelling through Wales I would arrive in England to coincide with the first hatching of chicks. Six weeks after setting out, I would finish on the East Anglian coast as the fledglings were beginning to try out their wings. Here I would mark the place where many curlews would come to spend the winter.

This would be a journey of many layers. A geographical one from west to east through the variety of landscapes that range across Ireland and the UK, places that are at once familiar and yet still mysterious. I wanted to see where the birds are surviving, but also experience their absence from the fields that no longer host their songs. It would be a walk through a year in the life of curlews. I would watch them displaying to their mates, soaring on fresh winds over fields just emerging from winter, and then I would search for their hidden nests in meadows and on moorland. If I was lucky, I would see their young, all feet and feathers and beady eyes. This would also be an artistic journey to explore the many connections that curlews have to poetry, literature, art and music, both in the past and today. But, most of all, I wanted to really understand what it is that is edging them closer to extinction, the environmental problems that are so huge that we are in real danger of losing them as a breeding bird across Ireland and the UK.

All this I decided at the start of 2016, when curlews were still on winter-cold estuaries and coasts. This is when they are easiest to see, gathered together for safety on mudflats, beaches or wet coastal grasslands. It would be a chance to think about the walk ahead, surrounded by the birds that mean so much to me. The nineteenth-century poet Helen Maria Williams wrote in her poem, ‘To the Curlew’:

Soothed by the murmurs of the sea-beat shore,

His dun-grey plumage floating to the gale,

The Curlew blends his melancholy wail,

With those hoarse sounds the rushing waters pour.

And so I started the year where the walk would end – on the east coast of England.