Читать книгу The Quest for the Christ Child in the Later Middle Ages - Mary Dzon - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Introduction

Recovering Christ-Child Images

I will rise, and will go about the city: in the streets and the broad ways I will seek him whom my soul loveth: I sought him, and I found him not. (Song of Songs 3:2)

Medieval Christians’ Desire to Know About Jesus’ Childhood

In The Book of Margery Kempe, the story of a fifteenth-century English woman who, desiring a more spiritual way of life, parted from her husband to go on pilgrimages, we learn about how she wandered along the streets of Rome in hopes of stumbling upon Jesus, come to earth again, as a handsome man or as a darling baby boy. Margery would apparently have been pleased just to find a male who resembled and thus reminded her of her divine beloved. While her rather frantic and unconventional search for Jesus attracted attention and in many cases scorn from her fellow Christians in England and abroad, she was nevertheless a product of the religiosity of her times, not least in her devotion to the baby Jesus.1

As many scholars have observed, in the high Middle Ages (basically, the period stretching from the eleventh century and into the thirteenth) a new emphasis was placed upon the humanity of Christ, particularly the sufferings he endured in his Passion. Men and women living under religious vows, as well as the laity, began to concentrate more closely on the historical life of Jesus, especially his dramatic death—a trend that intensified toward the end of the medieval period. Through meditation on the events of Christ’s human existence, often with the aid of devotional books and images, Christians sought to gain a deeper understanding of the God-man who came to earth to redeem sinful humanity. The liturgical year, like the Creeds, had for centuries called Christians’ attention to the two main events of Christ’s life—his birth (at Christmastime) and the sufferings that culminated in his salvific death (in Holy Week). Yet it took roughly a millennium (from the time of Christ) before Europeans sought a deeper, more intimate—and, in many cases, intense—relationship with the God of love who became a little baby, lived, worked, and pursued his ministry within a Jewish community, and then suffered a brutal and ignominious death.2 Even medieval religious writers who stressed that the ultimate goal of the spiritual life was union with the deity, a pure spirit, often encouraged Christians to become more familiar with Jesus in his sacred humanity; by virtue of his concreteness, God the Son was accessible to an array of people at different levels of the spiritual life.3 While reflection upon the life of Christ was intended to produce feelings of compassion, love, and gratitude, it also provided an exemplar that ideally guided Christians’ actions.4 The high Middle Ages witnessed new religious movements that strove to return to the vita apostolica practiced by Jesus’ first disciples, as described in the New Testament, and epitomized by Christ himself—a man detached from worldly things, who ministered to those in need and preached salvation, before suffering on the cross.5 By the later medieval period, Christ the Almighty, whose divine retribution at the Last Judgment traditionally instilled fear, became for Christians a human being to be imitated and loved, on account of his labors and sacrifices on their behalf, as well as his innate goodness. Nonetheless, believers did not lose sight of Jesus’ divinity, as we shall see when considering the figure of the Christ Child in the later Middle Ages (generally speaking, the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries).

A desire to know more about Christ’s humanity undoubtedly impelled medieval Christians to seek greater knowledge of the events that constituted his life, in its various stages. In other words, curiosity about Christ, linked with a desire to be like him and to share in his sufferings, was a factor in the development of christocentric piety. Significantly, biblical exegetes began to pay more attention to the series narrationis of the biblical text at about the same time that the literary form of the romance emerged in Western Europe—a genre that focuses on an individual’s experiences over time, or at least on the most exciting and memorable incidents.6 It was thus natural for Christians to desire a more detailed, if not fully sequential account of Jesus’ life. Scripture, however, says very little about Jesus’ birth, even less about the marriage of his parents, and almost nothing about his childhood and adolescence. Only two of the four Gospels tell us something about the beginning of Christ’s life. The Gospel of Luke (chapter 2) recounts Jesus’ birth, the visit of the shepherds, the Child’s circumcision, and his Presentation in the Temple; it then skips to the time when Jesus stayed behind in Jerusalem at the age of twelve. The Gospel of Matthew, the only other canonical gospel that discusses Jesus’ early life, tells (in chapter 2) how the Magi visited the Christ Child and paid him homage, after which Herod ordered the slaughter of the Innocents. To avoid the mortal blow intended for the baby Jesus, the Holy Family fled into Egypt, where, according to Matthew, they lived for an unspecified duration of time, and then later returned to Judea after Herod’s death. The Gospels of Mark and John simply skip over Jesus’ infancy and childhood, basically beginning with Jesus’ public debut at his baptism (which John, for his part, recounts after his famous prologue about the Incarnation of the divine Word). The “hidden” years of Christ’s childhood, which remained a mystery to Christians due to the discontinuity of the Gospel narratives of Luke and Matthew and the complete silence of the other two, obviously posed a problem for Christians who wished to reflect upon the humanity of Christ in all of its stages and aspects.

This book will explore some of the ways in which medieval people tried to make inroads into the early period of Christ’s life, which encompasses his infancy, childhood, adolescence, and youth, prior to his public ministry (as presented in the canonical gospels). Although the highly influential early medieval encyclopedist Isidore of Seville demarcated and defined these first four ages of the human life cycle (the first two of which last seven years, the third fourteen years, and the fourth more than twenty years!), medieval authors were not always so precise and not always consistent in their use of terminology pertaining to the stages of human life.7 In this study I will focus on medieval depictions and discussions of the young and (more frequently) the very young Jesus; I will often refer to Christ’s hidden years as his “childhood,” broadly construed, though by the phrase “Christ Child” I usually have in mind a younger, preadolescent Jesus (which, in terms of the New Testament’s presentation of him, means Jesus before or during the Finding in the Temple episode).

How did medieval people deal with the difficult situation of wanting to know more about Christ’s childhood yet lacking ample information, it seemed, from the Bible as well as the liturgy? One approach was for Christians to turn to ancient apocryphal legends about the Christ Child and his family, or, if they were already familiar with some of them, to further their knowledge of such lore. Besides providing many interesting details, these legends laid claim to some authority, which stemmed from their supposedly being written by those who knew the Child (and his parents or the Jewish community in which they lived); at the very least, these stories derived credibility from purportedly being woven from the narratives of reliable witnesses.8 Crafted as historical accounts written by reputable authors, these narratives seem to have had a popular appeal. Yet as victims of their own success, it seems, within a few centuries of their composition they suffered the fate of being listed in the so-called Gelasian Decree (sixth century) among the many “apocryphal” books that the Church rejected, largely because of the perceived uncertainty surrounding their authorship. In other words, they were not accepted as being part of the official canon of biblical writings and could not be read in church.9 Even though they lacked the indubitable authority of the inspired Scriptures and aroused ecclesiastical suspicion, these apocryphal infancy texts were still considered valuable as sources of information about the births and childhoods of both Mary and Jesus.10 Christians’ willingness, in the later medieval period as well as earlier, to give credence to numerous details from the apocryphal infancy narratives is understandable considering that believers, many of whom were not literate, did not rely solely on Scripture and on official Latin texts and ecclesiastical teachings for the contents of their faith, but also looked to oral traditions and vernacular culture.

There were other possible approaches if one wished to know more about the Christ Child and his parents but did not wish to resort to apocryphal legends, which indeed had a certain aura of dubiousness about them. Focusing on reliable, biblical texts, one could seek greater knowledge of the early stages of Christ’s life through careful study of Scripture, by linking together passages that directly deal with the Christ Child with verses from different parts of the Bible that seemed applicable to him. Medieval Christian scholars viewed many passages from the Hebrew Scriptures as prophecies of, or encoded references to, the child Jesus, and such typological readings were transmitted to broader audiences.11 Another approach, one that seems to have yielded a more diverse outcome, was the retrospective application of the New Testament’s presentation of the adult Christ to Jesus’ boyhood, according to the common view that famous or saintly people were biographically consistent over the course of their lifetime. So, for example, if Jesus when he was a preacher spoke of himself as “meek and humble of heart” (Matt. 11:29), then it only stands to reason that the child Jesus would have been like that, too. On the other hand, the adult Jesus’ conflicts with the Jewish authorities suggested to some medieval Christians that he likely experienced opposition from Jewish elders (or those who were to become such) early on: just as he healed a blind man on the Sabbath using moistened clay (John 9:1–15), so also in his childhood, one might have reasoned, he fashioned clay birds at a riverside in violation of the Jewish day of rest.12 Related to this notion of biographical consistency is the popular belief that people destined for greatness give signs of this early on, as baby Hercules famously did when he killed the snake insidiously placed in his cradle.13 Yet not everyone was willing to take a more fanciful approach to Jesus’ childhood, or, on the other hand, had the training and leisure to study the Bible’s numerous (both clear and subtle) references to Christ as a way to discover something about his childhood. A conservative yet still somewhat creative approach was for a Christian to meditate prayerfully on scenes or episodes from Jesus’ early life, which are mentioned in the canonical gospels and commemorated in the liturgy, using his or her imagination to yield further details, which, if not completely accurate in a historical sense, were at least conducive to devotion. One could also aspire to supernatural communication with Jesus and Mary themselves, who might graciously reveal information about Christ’s childhood or help one reenvision it, as it transpired long ago within the household of the Holy Family and the village in which they lived—details that would have otherwise remained hidden. In short, medieval Christians who wished to gain a greater imaginary hold on the early part of Jesus’ life clearly had a variety of approaches at their disposal; besides turning to the apocrypha, they could study Scripture, pray and meditate, and also think of Jesus’ youth in terms of more contemporary constructs (such as late medieval ideals of masculinity).

A Shift in Medieval Christians’ Response to the Divine Child

In the patristic and early medieval periods, religious writers focused not so much on the early events of Christ’s life as a way to draw Christians closer to Jesus, but on the paradox of the Incarnation—of God condescending to become a human being—surely a great cause for wonderment.14 How was it possible for Mary’s womb to contain the Lord of the universe, who is “the wondrous sphere that knows no bounds, that has its centre everywhere and whose circumference is not in any place”?15 Another paradox frequently propounded by early writers was the transformation of the Eternal Word into an infans—literally, one who does not speak.16 While Christians during the first fifteen hundred years of the Church continuously wondered at God’s becoming a child and the paradoxes that followed thereon, it seems generally to be the case that, starting around the late eleventh century, more attention was paid to Jesus’ humanity per se—that is, not simply as a way to highlight the contrast between Christ’s divine and human natures. The experience of wonder arguably shifted in emphasis, with less weight being given to the intellectual stupefaction resulting from the awareness of paradox and more to the delight produced by the approachability of a God who became a lowly infant and simple child.17 In one of his Christmas homilies, the eleventh-century Italian monk and reformer Peter Damian, who is sometimes seen as a herald of the new concentration on Christ’s humanity, evinces the emotion of wonder as he calls attention to the Christ Child’s humanity, yet, at the same time, he does not seem to foster an emotional or imaginative interaction with the baby Jesus. Damian thus seems to stand at the end of a long tradition of Christ-directed piety:

Who would not be astounded that he who is not held in by the vastness of heaven is laid in a narrow manger? He who clothes his elect with the stole of immortality does not despise being covered by base rags. He who is the food of angels reclined on the straw of beasts. He who quells the storms of the sea … awaits the precious drops of milk from the Virgin’s breast…. The little infant who is tightly bound in a child’s swaddling clothes by his mother is the immense one who, with his Father, governs the rights of all things. O how great were the castellated palaces of the world’s kings … and yet he who chose the manger as the crib of his Nativity despised all those things…. He wished to be cast down so that he might carry us to the heights; he became a poor person in this world, so that he might present us partakers of his riches. Dearly beloved brothers, ponder the humility of our Redeemer with all the contemplation of your soul.18

Damian in this passage is concerned with eliciting a response of loving gratitude and joy based upon an intellectual and imaginative realization of what the Incarnation really means: Christ deigned to become a poor and powerless child so that he might generously share his divine wealth with lowly human beings. Who would have thought of such a thing!

In the following century, the eloquent Cistercian abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, in one of his sermons for the Vigil of Christmas, claimed that the belief that God united himself with humanity and that a virgin became a mother was itself a cause of wonder, since it entailed the coupling of faith and the human heart, which, by implication, is naturally inclined to disbelieve the pairing of polar opposites. Bernard uses striking language to speak of these three conjunctions, stating, for example: “Majesty compressed himself to join to our dust (limo nostro, literally, ‘our mud’) the best thing he had, which is himself…. Nothing is more sublime than God, nothing is lower than dust—and yet God descended into dust with great condescension … a mystery as ineffable as it is incomprehensible.”19 Further in the sermon, Bernard reconsiders the wonder implicated in belief in the Incarnation, asking rhetorically: “Are we to believe then that the one who is laid in the manger, who cries in his cradle, who suffers all the indignities children have to suffer, who is scourged, who is spat upon, who is crucified … is the high and immeasurable God?”20 Though Bernard here briefly mentions concrete aspects of Christ’s babyhood, he does not urge his audience to savor such homely details. Elsewhere, in a sermon for Christmas day, he leads his reader to a more personal reflection on the lowliness of Christ’s Nativity: “I recognize as mine the time and place of his birth, the tenderness of the infant body, the crying and tears of the baby…. These things are mine … they are set before me, they are set out for me to imitate.”21 In this passage, while he praises God’s wisdom, Bernard focuses on the example of asceticism provided by the infant Word; God did not become human by assuming the form of a strong man—in the view of many, the most impressive type of human being—but “became flesh, weak flesh, infant flesh, tender flesh, powerless flesh, flesh incapable of any work, of any effort.”22 The helplessness of the baby Jesus, lying in the manger, underscores the weakness of all human flesh, including that of monks who were supposed to discipline their body continually, in order to overcome pride and subdue fleshly desires.

Though Bernard approaches his subject rhetorically rather than scholastically, he shares a sentiment with high-medieval intellectuals who wondered at the tenderness of infants’ bodies. I refer here to how some scholars pondered why God, the author of nature, made it much easier for the babies of animals to move about on their own and seek food. The new Aristotelianism that partially prompted such questions may very well have led to greater reflection on the human nature of Jesus, who was thought to have truly passed through the early stages of the human life cycle. In other words, Jesus was believed to have experienced what other babies, children, and adolescents experienced—to be like us in all things but sin (Heb. 4:15).23 Another possibility was that Jesus simply gave the appearance that he was developing, as he non-dramatically bided his time until undertaking his adult mission.

Thus far, I have sketched out a broad picture of how Christians roughly in the first millennium and a half of the Christian era regarded the God-Man who, among other surprising things, had chosen to begin his earthly existence as a little child. The desire to know more about the Savior was probably always present among Christians. But as the centuries passed, believers felt a greater urge to delve into the human aspects of Christ’s existence, to imagine what it was like for Jesus to have been a helpless baby and then a growing boy. Although acknowledgement of the union of the two natures in Christ must have always been a cause of wonderment, Christians in the later Middle Ages seem to have approached this mystery on a more personal level, reflecting, for instance, on how the lowliness of their own humanity was willingly assumed by the Son of God. Yet as we shall see, though God became more approachable, especially in his childhood form, Christians continued to reverence his mighty power and mysterious transcendence, which were recognized even in the boy Jesus.

Previous Scholarship Pertaining to the Medieval Christ Child

Although scholars focusing on Mary or the adult Jesus occasionally mention the child Jesus, there has been no broad-reaching, single-authored study of this figure specifically in the medieval period, as William MacLehose has observed.24 This is the case, despite the fact that the Christ Child was the object of intense devotion in the later Middle Ages, and was a pervasive presence throughout medieval society. Scholars can find traces of the Christ Child’s influence even in areas where we might not expect to encounter evidence of the power and allure of Jesus as an infant or boy, such as papal politics, the crusade movement, intercultural relations, and the dynamics within local communities and domestic settings.25 While people looked for and esteemed the traces of Jesus’ early years on earth, often traveling great distances and enduring many hardships in order to make contact with the remnants of his historical past,26 medieval Christians acted as if Jesus still existed as a child and was accessible to them in their own settings—at home, in the convent, and in the nearby parish church. Writers and artists frequently spoke of and represented the Christ Child in their works, ostensibly with the goal of linking Christians with Jesus’ past and also of underscoring the living reality of Christ as a child with whom they could engage in the present. Ironically, the widespread presence of the Christ-Child figure within medieval culture may largely explain why he has not received a tremendous amount of critical attention from modern scholars, who may acknowledge his importance but consider it a constant and steady feature rather than a crucial factor within, or indication of, a particular medieval cultural setting.

The following brief overview of some of the scholarship on the medieval cult of the Christ Child will suggest further hypotheses as to why this area of research has not flourished more bountifully. To start with the more recent: The Christ Child in Medieval Culture, a 2012 essay collection I coedited with Theresa Kenney, focuses on later medieval sources, both textual and visual. In that book, which brought together scholars from a range of disciplines, Kenney and I sought to orient future scholarship in the field by exploring some of the key aspects of the Christ Child’s cult. The study was divided into three parts: “The Christ Child as Sacrifice,” “The Christ Child and Feminine Spirituality,” and, last, “The Question of the Christ Child’s Development.” Of these groupings, the third cluster of essays relates most closely to this current book, though the authors of those pieces did not intend to treat the issue of Christ’s childhood development systematically, with an eye to understanding the interrelationship of various sources. That part of the book simply offered three essays that dealt with the implications of medieval belief in Jesus as a real child, both physically and psychologically. From that section, Pamela Sheingorn’s chapter on two medieval Italian textual reworkings of the apocryphal legends about Jesus’ childhood, in my opinion, complements the present study particularly well. Sheingorn takes a microcosmic view of the apocryphal infancy tradition, focusing on two illustrated manuscripts (which contain related but substantially different narratives), whereas my approach to the apocryphal legends in this book is much more general. As I explain below, here I am interested in demonstrating the broad influence of the apocryphal tradition on later medieval culture. Hence it follows that although I mention (specifically in Chapter 3) some of the medieval manuscripts containing apocryphal infancy texts and illustrations, space does not permit me to focus on particular texts or manuscripts in great detail. In the Appendix, though, I offer a summary of the chapters in William Caxton’s Infantia salvatoris, which is fairly representative of the Latin narratives about Christ’s childhood circulating in the later Middle Ages.

Previous studies on the medieval Christ Child (that is, prior to the 2012 essay collection) tended to concentrate on two interrelated facets of the cult: first, the association of the child Jesus with the Eucharist, specifically the numerous cases in which he is said or shown to inhere in the consecrated host in a veiled manner, sometimes becoming visible to those who look upon the sacrament; and, second, his occasional appearance to and interaction with holy men and women generally considered mystics. The first approach is well illustrated by Leah Sinanoglou Marcus’s 1973 Speculum article “The Christ Child as Sacrifice: A Medieval Tradition and the Corpus Christi Plays,” which discusses conflations of the Eucharist and the Christ Child that we commonly find in late medieval drama and other sources, such as contemporaneous and earlier homilies. This classic essay has frequently been cited by medievalists and other scholars, not only because of its superb insights and impressive range, but also because other treatments of the child Jesus (in English and other languages) have been lacking.27 Caroline Walker Bynum’s numerous studies on medieval holy women constitute the prime example of the second, related category. Bynum frequently mentions the appearance of Jesus in the host, especially as he is savored by medieval holy women, who in a sense consume him, while denying themselves earthly food. Their gusto in relishing the baby Jesus may be summed up in an exclamation from a German nun whom Bynum quotes more than once: “If I had you, I’d eat you up, I love you so much!”28 Bynum also cites various instances of holy women enacting what were considered maternal roles and sentiments vis-à-vis the Christ Child, either meditatively, through the use of props, or with the Child himself, mystically reincarnated, so to speak, in their midst. Countering the pejorative view of some modern critics that such women were simply expressing their repressed femininity, for example, by naively playing with Christ-Child dolls or cradles, Bynum argues that such behavior, which was inextricably tied to the medieval discourse of women’s rootedness in the body, was consciously chosen and even enjoyed by women as an active mode of spirituality which they themselves could direct and excel at.

While the studies of both Bynum and Marcus are tremendously valuable, an accidental result of their successes has been that scholarship in the area of the medieval Christ Child has tended not to expand into other areas. In my view, when those of us whose work occasionally touches upon the medieval Christ Child cite such studies and then move on, without trying to learn more about medieval views of Jesus’ childhood, we run the risk of accepting a partial picture in place of a broader, more detailed landscape. A student of medieval culture in search of a summary of the medieval Christ Child prior to the 2012 collection may, understandably, have concluded that the child Jesus was simply a Eucharistic phenomenon or an important feature of female piety—the particular focus of women religious whose opportunities within the church were indeed limited. While the figure of the child Jesus certainly seems to have been appropriated differently by different genders,29 in my view, it is incorrect to regard him as mainly falling within the devotional purview of medieval women, a point supported by an observation made by Peter Dinzelbacher years ago in discussing christocentric piety among high-medieval mystics.30 So, we need to look more broadly at medieval sources touching or focusing on the Christ Child that were produced by, and for, men and women (and even possibly for children), examining different kinds of texts, images, and objects, not just those dealing with the Eucharist or centering around people regarded as saintly. Keeping the big picture in mind, we need to consider the Christ Child from various angles and the early part of his human life in relation to his adulthood and divinity, without limiting ourselves to a particular aspect of his personage or behavior, in isolation from the rest of his identity.31

The continuing influence of the apocryphal legends about Jesus’ infancy and childhood into the Middle Ages, and the role played by other imaginative texts, has, in my view, been obscured by the heavy emphasis of scholarship on mystical and Eucharistic encounters with Jesus. While these are certainly key pieces in the puzzle, they cannot stand alone as embodiments of medieval piety toward the Christ Child. Indeed, I suspect that the shortness and unpredictability of such supernatural encounters may, at least at times, have been frustrating to medieval Christians who wanted to enter more deeply into the mysteries of Jesus’ childhood—to advance along the quest for deeper knowledge of the divine child. When Jesus appears in the host as an infant or slightly older boy, the description we get of him usually emphasizes his amazing beauty, but it is nevertheless often tantalizingly nondescript; concomitantly, the duration of the vision or heavenly visitation is usually very short. Moreover, such mystical experiences were regarded as gifts rather than as something one could willfully lay claim to, though they could definitely be prepared for, especially by pious meditational reading, interaction with related artworks, pilgrimage to shrines, and attentive participation in the liturgy.

Margery Kempe, whom I mentioned earlier, felt the frustration of not having her wishes for a mystical experience with the child Jesus come true. Once when she saw some Italian women with babes in arms, who turned out to be, not surprisingly, just ordinary human infants, her “mende [was] so raveschyd into the childhod of Crist, for desir that sche had for to see hym, that sche mith not beryn [endure] it.”32 Nor did Margery, despite her imitation of earlier holy women, ever see the baby Jesus in the host, as he is said to have appeared to many female saints. Even though it may have seemed like a disappointment to her, Margery could still return to the devotional books she had access to back in England, which likely included a version of St. Birgitta of Sweden’s revelations, which, as we shall see, shed much light on the Christ Child. And if Margery was curious and persistent enough, she could have learned of the apocryphal tales of Jesus’ childhood, which at that time circulated in English and were also rendered artistically.

One of the reasons that medievalists have not pressed very far beyond such previous studies,33 extremely worthwhile and indeed essential though they are, is that the attention of scholars interested in medieval religiosity has been directed elsewhere. That is, recent studies on medieval devotion to the humanity of Christ have focused almost exclusively on the Passion of Christ and medieval Christians’ sacramental access to it through the Eucharist—the figure of the suffering Jesus, who, driven by love and exhausted from physical abuse, hangs on the cross, offering his body both as a propitiatory sacrifice and as spiritually nourishing food.34 Without a doubt, medievalists’ focus on the Man of Sorrows is both understandable and justifiable, given the centrality of this figure in the later Middle Ages.35 One valuable area of contribution within this latter field has been the recent work done on the anti-Judaic aspects of medieval treatments of the Passion and their unfortunate social consequences.36 Equally important has been the recent scholarship on devotion to the Virgin Mary in the medieval period, which has tended to focus on medieval approaches to the compassion she felt on Calvary or tales of her miraculous interventions in medieval people’s lives. In their concern about the undeniable historical meaning and importance of Mary, these studies often gesture at, if not actually grapple with, contemporary feminist/gender issues.37 Such contemporary concerns have probably resulted in more attention being paid to the medieval Virgin Mary than to the medieval Christ Child, even though interest in historical or other types of childhood studies has grown over the last fifty years or so. Still, medievalists do not seem to have felt a strong exigency to explore the medieval Christ Child more thoroughly. This deficiency largely accounts for the synthetic and interdisciplinary nature of the present study, which (though limited in scope) aims to bring together and explore some of the ways in which medieval Christians imagined Jesus in the early part of this life.

To be sure, we would have a much better understanding of medieval piety if we knew what it was about the figure of Mary that inspired, among many other things, a young man to wed himself to her, solemnizing the dedication of his heart to this lovely lady by placing a ring around the finger of her effigy. The Praemonstratensian canon Hermann-Joseph of Steinfeld (d. 1241) indeed performed this ritualistic and deeply meaningful gesture in his youth, if we can believe his hagiographer.38 Yet Hermann-Joseph also played with the Christ Child when he was a boy, having been invited to do so by Mary (who supposedly communicated with the pious youth through a statue of the Virgin and Child). As we shall see, in the later Middle Ages, many people interacted with the child Jesus, sometimes on a one-on-one basis. An animated statue of the Virgin and Child comes into play in another tale, a Miracle of the Virgin found in a thirteenth-century manuscript: when a nun was at prayer, the Christ Child spoke to her and instructed her sometimes to say “Ave benigne Deus” to him (by implication not simply the “Ave Maria” to his mother).39 Although medieval Christians sometimes seem to have focused on either Mary or the Christ Child, these figures were thought to be inextricably intertwined on account of their perpetual maternal-filial relationship.40 Arguments in favor of Mary’s bodily Assumption in fact drew attention to her loving care of and constant companionship with her son during his lifetime, implying that it would be impossible for Jesus not to reciprocate his mother’s love by having her beside him in heaven.41 That Mary and Jesus are closely linked by an enduring bond is likewise conveyed by an exemplum recounted in the Legenda aurea of Jacobus de Voragine, an immensely popular collection of saints’ lives from the thirteenth century: a woman who wanted to liberate her imprisoned son devised a novel yet effective plan. She detached an image of the baby Jesus from a statue of the Virgin and Child, took the effigy home with her, and locked it in a cupboard in order to force Mary to help her regain her son. This the Virgin promptly did, in order to recover her own beloved child.42

To sum up: in this section I have shown how there has previously been no broad-ranging study of the child Jesus as a focus of devotion and curiosity specifically in the Middle Ages, though a number of studies dealing with related aspects of medieval piety (and Christianity more generally) have explored important aspects of the medieval Christ-Child cult. Scholars interested in the ideas and social realities surrounding childhood in the Middle Ages have also touched upon this central figure within medieval culture.43

Studying the Christ Child and Medieval Childhood

At the outset, it is worthwhile stating my view that, given the inherently theological character of medieval images of and legends about Christ, they seem to have only a limited capacity to shed light upon medieval childhood (a difficult, though rewarding area of research, due to the relative scarcity of medieval sources focusing on children or childhood). Nevertheless, studying the medieval Christ Child can give us some indication of how medieval adults thought of and treated children.44 An example of this occurs in the vita of Ida of Louvain, a thirteenth-century Cistercian nun, which tells of a vision that Ida had one night, in which a lovely-looking boy Jesus, wearing a full-length seamless tunic, appeared to her sister who had badly mistreated her that very day. Climbing onto her bed, he proceeded to “overpower her with his punching fists and kicking feet.” He also “added bold outspoken words, in which he took her to task for the stupidity and wickedness behind her upbraiding of her sister [Ida],” who was accustomed to caring for him.45 This vita provides another naturalistic view of Christ as a normal human child (though in a more positive sense), in its account of Ida’s vision of being privileged to assist St. Elizabeth, Jesus’ aunt, in bathing him. First the women arranged the bathtub and the other things that were needed: “Then Elizabeth, along with Ida, carefully sat the Infant in the lukewarm water to be bathed. Seated there, this Choicest of Children cupped his hands and clapped on the water—as playing children will do. He toyed with the waves he stirred and he splashed [water onto] the floor all around.”46 Commenting on this passage, social historian David Herlihy remarks that “the male author of this life had clearly observed babies in the bath, and noted the delight which real mothers took in washing their infants.” 47

Just as sources dealing with the Christ Child have the potential to reveal medieval perceptions of children and attitudes toward childhood, so the study of medieval childhood helps situate medieval representations of the boy Jesus within the broader culture. For instance, knowing that swaddled babies, in medieval art, look very similar to deceased infants (who are similarly shrouded) helps us appreciate why the Christ Child in Nativity scenes is frequently depicted tightly swaddled, lying on a block-like, almost tomb-like manger. Such images represent the newborn Jesus as a sacrificial offering, placed, as it were, upon the altar at Mass. The Infant’s swaddling clothes, with their connotations of burial, foreshadow the adult Christ’s shroud and thus his future death, an association with perhaps more poignancy for medieval viewers, who dealt with deceased infants much more regularly than we do.48 To take another example, one from day-to-day life: knowledge that medieval mothers were often responsible for the education and formation of young children infuses greater realism into medieval images of Mary interacting with Jesus, as if to instill in him basic skills or knowledge about the world around him, if not also to confer with him regarding his future mission.49 Medieval sources probably had an even more powerful effect on their audiences when they involved a reversal of cultural norms; for example, some medieval texts and images suggest that the child Jesus actually instructed his mother about the suffering that lay ahead for both of them.

Other scholars have recognized the connection between medieval childhood and the medieval Christ Child as interrelated phenomena. In a wide-ranging essay on medieval childhood, originally published in 1978, David Herlihy argued that the urbanization of Western Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries and the dangers posed to children’s lives from contemporary social upheavals resulted in a greater “willingness on the part of society to invest substantially in [children’s] welfare [and] education.”50 Herlihy provides some evidence for adults’ concern that their children acquire marketable skills within the new urban economy, and also some indication of adults’ (presumably new or newly reflected upon) understanding of the particular nature of children. While noting that monks in the earlier Middle Ages, according to the sources, tended to praise children’s virtues and treat them humanely, Herlihy claims that the Cistercians in the twelfth century started a new trend of idealizing childhood, which later appealed to the laity, who sometimes felt burdened by materialism—an idea that complements my suggestion below that medieval adults desired somehow to reappropriate the simplicity of childhood. Herlihy boldly proposes that the “widespread devotion to the Child Jesus,” which developed from the twelfth century onward, and was strongly promoted by the Cistercians and Franciscans, stemmed from the appeal of childhood itself—an intriguing hypothesis that, intuitively, seems to have a good deal of truth to it.51

While investigations that consider the synergy among ideas about and images of childhood on the one hand and of the Christ Child on the other are definitely valuable, I would stress the importance of keeping in mind the diversity that existed within the latter category—a multiplicity that reflects the inherent difficulty medieval people faced when pondering the deity’s having become a child. Not only was God challenging (indeed impossible) for medieval Christian adults to comprehend, but so, too, it appears, was the very nature of a child. Studying the medieval Christ Child sheds light on this mystery, as medieval people perceived it—something that the other sources examined by social historians do not often convey, even though they may indicate parents’ emotional investment in their offspring, for example.52

Adding More to the Mix: Appealing Images of the Child, Yet None Completely Authoritative or Fully Satisfactory

Herlihy’s hypotheses that the emergence of a new urban economy led to a greater concern for and awareness of children, and that the idealization of children helped to relieve the stresses of day-to-day life for medieval adults, are certainly plausible. Yet his explanation for the new European interest in the Christ Child seems reductionistic. In sum, Herlihy says that what lay and religious people of the later Middle Ages most admired about the Christ Child was his childlikeness.53 Although a number of medieval sources call attention to the ways in which Jesus embodies the positive, natural virtues of children,54 most of the texts and images examined in this present study do not have this emphasis. Herlihy rightfully draws our attention to the successful efforts of the Cistercians and Franciscans to promote devotion to the child Jesus, but the members of these two groups did not simply portray the boy Jesus as a sweet and charming child, worthy of love and emulation on a basic human level. There were other ways in which the Child was presented and regarded, by various groups and individuals, in the high and later Middle Ages.

As we shall see in Chapter 2, for the twelfth-century Cistercian Aelred of Rievaulx, the Christ Child is the mystical bridegroom for whom the soul yearns and toward whom it makes progress, especially by retracing the key events of Christ’s early life. While Aelred, in one section of his well-known treatise on the twelve-year-old Jesus, sketches a picture of Christ as a charming child, he clearly wants his reader to go beyond such a conceptualization and visualization by developing spiritually, specifically through the cultivation of the virtues. In this treatise, Aelred also speaks derogatorily of the Jews, ostensibly to present a stark alternative: allegorizing the story in Luke about the loss of the twelve-year-old Jesus, he says that the Jews (represented in this episode by Jesus’ parents) have great difficulty finding the Messiah. By implication, Aelred’s monastic reader should do what it takes to avoid losing Jesus, and thus avoid the grief experienced by Jesus’ parents and the other members of the Jewish community who knew him. So, while Aelred deserves credit for laying important groundwork for greater reflection on Christ’s childhood in the later medieval period, his main goal was clearly not to promote a fundamentally sentimental approach to the boy Jesus; his treatment of the Christ Child is definitely more complex. Such complexity exists among Franciscan sources as well. As I show in the latter part of Chapter 2, Francis of Assisi had, and promoted, a more affective response to the infant Jesus, whom he regarded as a poor boy worthy of tremendous compassion. Yet for the Italian saint and his Franciscan followers the Child was not merely a darling bambino who captured their hearts. Much of their attention focused on the suffering that Jesus embraced at birth and throughout his life, which revealed the heights of divine love and was worthy of radical reciprocation. Moreover, the love of the Father who gave his Son to the world to redeem humankind—long ago in Bethlehem and in the present, on the altar at every Mass—was considered a cause of great rejoicing and also a mystery to be profoundly revered.

While it is true that the Cistercians and Franciscans invigorated the cult of the Christ Child for the later medieval period, as Herlihy emphasized, there were many Christians not belonging to or affiliated with these groups who fostered greater attention and a more intense response to the child Jesus—numerous men and women who in varying ways contributed to the historical cult of the Christ Child but who, for lack of space, cannot be featured here in detail (or, in some cases, mentioned at all). In terms of iconography, there was a range of images of the Christ Child in circulation; the “new picture of the Child Jesus,” whose humility and gentleness were attractive to medieval adults, did not simply supplant the old apocryphal portrayal of an “all-knowing and all-powerful” Christ Child, as Herlihy’s brief comments about the apocrypha seem to imply.55 The two main types of images he speaks of should, instead, be thought of as having competed with each other and, in many cases, overlapped with each other, as well as with other images. To be sure, in the medieval period there were not simply two types of Christ-Child figures, which were basically diametrically opposed, though it may be helpful to think of broad categories.

When we consider medieval iconography, we certainly perceive a difference between, on the one hand, the older Romanesque depiction of a hieratic, stern-looking Christ Child seated upon his mother’s lap, like a priestly or regal figure wielding influence from a throne, and, on the other hand, the more human Virgin and Child of Gothic art, who tenderly and playfully interact with each other. On the basis of the emergence of the latter, more approachable image, Philippe Ariès claimed that the seeds of the discovery of childhood in Western culture were sown in the later Middle Ages, when artists began to portray the child Jesus more realistically. Although it took a long time for this trend of realism “to extend beyond the frontiers of religious iconography,” he considered it “nonetheless true that the group of the Virgin and Child changed in character and became more and more profane: the picture of a scene of everyday life.”56 Though Ariès’s unsubstantiated (and rather ambiguous) remark that medieval society lacked a “sentiment de l’enfance” has rightfully been dismissed,57 he should surely be given credit for noting that a discovery of the Christ Child, so to speak, occurred in the later Middle Ages. A new outlook and sensibility did indeed arise, in the sense that the boy Jesus became the object of fresh attention and zeal, and that the implications of his having been a real child were pondered with new interest and open-mindedness.58

A little more than a decade after the appearance of Ariès’s book on the history of childhood, Leah Sinanoglou Marcus provided a brief though cogent overview of the medieval Christ Child as background for her literary study of Early Modern childhood. Despite the fact that her summary is quite insightful and still useful, it might lead one to think that a sentimental (fundamentally Franciscan) view of the Child predominated in the later Middle Ages:

From the beginning of the thirteenth century, the childhood of Jesus was portrayed with increasing frequency and realism. Latin nativity hymns from the fourth to the twelfth centuries are nearly all abstract treatments of doctrine just as visual depictions of the Christ Child from that period display him with hieratic formalism as the grave Incarnation of Divine Wisdom or the sacrificial Victim of the mass. But in the vernacular carols of the Franciscan Jacopone da Todi (1228–1306) the new affective spirit bursts forth. Jesus is “our sweet little brother,” called by the endearing diminutives “Bambolino” and “Jesulino.”

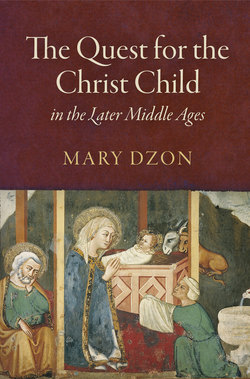

Figure 1. The boy Jesus reverenced as king by other boys, in an illustrated Vita rhythmica manuscript. London, British Library, Add. 29434, fol. 57v (fifteenth century?). By permission of the British Library Board.

Drawing a sharp contrast between a more intellectualized and a more affective Christ Child, Marcus sums up the emergence of a new image of Jesus by saying that, in the later Middle Ages, “the Infant Jesus leapt out of his Byzantine impassivity and became recognizably infantile, laughing, sucking the pap, or playing with fruit and toys.”59 A new iconography definitely emerged, yet the older images did not simply disappear. While Marcus’s succinct account of the later medieval Christ Child is impressive, it involves some exaggeration and oversimplification (Jacopone is surely not conventional).60 Images of a jocund Christ Child who noticeably laughs or even smiles are actually difficult to find.61 And evidence is lacking that Francis himself referred to Jesus as “our sweet little brother,” though the sources definitely indicate that the saint was deeply touched by the humility and lowliness that God manifested in becoming a human child. Significantly, in the twelfth- to fifteenth-century Latin and Middle English texts that I concentrate on in this study Jesus is not referred to endearingly, as far as I am aware, as “little brother.” This is not to deny, however, that some medieval authors, reflecting on mankind’s new familial relationship with God made possible through Mary’s divine motherhood, spoke of Jesus as our “brother.”62 In contrast to sources that call attention to the deity’s approachability on account of the Incarnation, the late medieval redactions of the apocrypha recount how Jesus’ childhood friends and the adults with whom he came into contact often called him “Lord.”63 Such reverence can extend even further: in an illustrated late medieval manuscript that retells a number of the apocryphal infancy legends, the boy Jesus is shown seated on a throne and reverently crowned by two boys, while a number of other boys who surround him kneel in obeisance (London, British Library, Add. 29434, fol. 57v; fig. 1).64

Proceeding from, Rather than Searching for Origins

This book, which gratefully acknowledges the contributions of previous related scholarship, which I have sought to synthesize and build upon, takes the mid-twelfth century as its starting point; it by no means aims to provide an encompassing history of the ideas, images, and emotions surrounding the Christ Child over the course of the first millennium and a half of Western Christianity, or even during the European Middle Ages. While some medievalists may choose to concentrate on the crucial turning points in medieval culture or to sort out which historical personages were most instrumental in the emergence of new developments, that is not my approach here, mainly because I am ultimately interested in the medieval reception of the apocryphal Christ Child and the relationship of the apocryphal legends to other roughly contemporary sources. I begin, in a sense, in medias res with well-known Cistercian and Franciscan saints and other figures, without giving a great deal of attention to their precursors or contemporaries, such as the numerous holy women and men who likewise embraced christocentric piety and imitatio Christi, and showed a notable degree of interest in Jesus as an infant, child, or youth.65 I have purposefully limited my focus to the later medieval period because of the abundance and richness of the relevant sources dating from this time. As a result, I survey in this book a range of texts from the high and later Middle Ages that attempt to provide a fuller picture of the child Jesus—texts that for the most part seem intended to help their readers progress along the quest of finding the “hidden” Christ Child, and also acknowledge the impossibility of completing that quest on earth.66 I primarily examine works that may be broadly classified as devotional literature,67 periodically mentioning medieval exegetical, theological, liturgical, dramatic, and lyrical texts; this book thus encompasses various types of religious literature pertaining to the Christ Child, with special attention paid to works whose readership extended beyond those who were highly educated. While I give priority to late medieval redactions of the apocryphal infancy legends, I intentionally focus on an assortment of sources, both medieval and patristic, that originated from different parts of Europe, as well as the Eastern Mediterranean.68 This study also explores, though to a lesser extent, related visual sources, and other forms of material culture, such as relics and the physical aspects of pilgrimage. My overarching goal is to provide a broad conceptual and categorical map that will amply illustrate the influence of the apocrypha on later medieval writers who attempted to reconstruct Jesus’ early years in diverse ways—a wide-ranging yet focused picture that will help frame future studies. Therefore, none of my primary sources are treated exhaustively, neither those I explore in detail, nor those I mention briefly, mainly for comparison’s sake. My aim is to argue for intertextuality—or, more specifically, a synergy among sources—rather than to produce a comprehensive and meticulous cultural history of the Christ Child throughout the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, what I offer covers much literary and intellectual territory. It is my wish that the broad argument of this book and the numerous details contained therein will serve as a guide to other scholars, especially given the lack of previous work in this field.

A Study of Different Identities for the Child Jesus—Commonly Linked with the Apocrypha

To recap and forecast the major threads of this study: in a general sense, the present book shows Christians’ tendency in the later Middle Ages to regard the Christ Child as an individual with whom they could communicate, in whose experiences they could share, and whose historical interactions with others (such as his family members and neighbors) they hoped they could better understand and profit from spiritually. My exploration of the Child’s cult illustrates Christians’ desire to make progress on a quest for deeper spirituality and greater knowledge of the God-man, Jesus Christ, through the use of various texts, objects, and artworks that shed light on the hidden years of Jesus’ youth. As we shall see, certain aspects of late medieval culture were incorporated (probably unconsciously) into diverse imaginative attempts to reconstruct Christ’s childhood and youth. This imaginative appropriation is readily apparent in the case of the early Franciscans, who thought of the child Jesus as a pauper like themselves. One can also sense that, within late medieval culture, parallels were perceived between the infant Jesus and the supernatural beings of medieval folklore: incubi, changelings, and demons who appear in human form.69

At the same time that writers added color to their portrayals of the young Jesus by incorporating new details that stemmed from the constructs and objects with which they themselves were familiar, they relied upon ancient traditions of both a popular and theological nature. These include the belief that Christ was, at least in a non-physical sense, a perfect person from the beginning of his life,70 an idea which, on the face of it, seems at odds with Luke’s remark (2:52) that Jesus progressed as he grew up (increasing “in wisdom, and age, and grace with God and men”). The view that the Christ Child was perfect—a human fully developed psychologically, due to his divinity—can be perceived in the fourteenth-century Meditationes vitae Christi and in other sources. As Jaime Vidal points out, we might assume that the Christ Child of this Franciscan-authored devotional text (whom the reader is invited to embrace lovingly and relate to in other tender ways) is simply a literary version of contemporary Gothic depictions of Jesus as a recognizably human child.Yet the case is more complex: the Christ Child of the Meditationes vitae Christi is not simply a charming and loveable boy. Insofar as he is also endowed with uncannily mature characteristics, the Christ Child of the Meditationes can be said to resemble Romanesque-Byzantine portrayals of the child Jesus:71 the Romanesque image of a little man, seated on his mother’s lap, as if on a throne,72 or the Byzantine image of “Christ Emmanuel,” a depiction of a serious and wise-looking Boy, portrayed in isolation from his mother.73

In the Meditationes vitae Christi, we do indeed find a less childlike, if not completely hieratic, Christ Child in the account of the Epiphany, where Jesus “watches [the kings] benignly, with maturity and gravity, as though He understood them.” After they lay their gifts at and kissed his feet, the “wisdom-filled boy (puer sapientissimus) also stretched out his hand to them to be kissed, to give them greater solace, and to strengthen them in his love. He made the sign (of the cross) and blessed them as well.”74 As Burrow remarks in his study on the importance of gestures in later medieval literature, “to kiss someone’s hand, leg, or foot evidently humbles the kisser and signifies respect.”75 Yet the regal and gracious Jesus depicted here seems concerned, not just with the respect he deserves, but also with his visitors’ well-being, in a way allowing himself to be kissed as “a sign of Catholic unity, as … when a guest is received.”76 Even more friendly interaction between the infant king and the Magi can be seen in a fourteenth-century fresco depicting the Adoration in the Monastery of the Sacro Speco of St. Benedict in Subiaco (fig. 2), in which the baby Jesus places his hand on the eldest king’s snow-white head, the latter’s crown having been removed. Here, as in other devotional works, the old man is shown kissing the Infant’s bare feet, a demonstrative act of reverence and supplication.77 Regardless of what exactly the baby Jesus is said or seen to do in numerous Epiphany scenes, “the image of a mere baby receiving the homage of grown men … forcefully expresses the transcendent standing of the incarnate God in his relation to human hierarchies…. Old men submit to infants.”78 In short, medieval texts and images that focus on the Epiphany often underscore the paradoxicality that medieval Christians perceived in the Christ Child.

While the child Jesus throughout the medieval period was regarded by orthodox Christians as both God and man, there are differences—both striking and subtle—in how he is portrayed. Such differences give us some indications of how artists, writers, thinkers, and more ordinary people viewed the relationship between Christ’s two natures. To be sure, Christians’ attempt to understand the so-called hypostatic union was, to say the least, challenging. Traditionally, it has been considered erroneous to think that Jesus’ two natures were blended or otherwise modified by their intimate association within the person of Jesus Christ. Joseph Ratzinger recently reiterated this idea, in a book on the canonical infancy narratives, where, at one point, he discounts the idea that Greco-Roman myths offer parallels to Jesus’ virgin birth. Restating traditional doctrine, Ratzinger forcefully emphasizes that “in the Gospel accounts, the oneness of the one God and the infinite distance between God and creature is fully preserved. There is no mixture, no demi-god.”79 Despite this perennial orthodox teaching, medieval Christians, as we shall see, sometimes verged on getting things wrong: coming close to or apparently detracting from (if not wholly discounting) the perfect divinity of Christ, by laying too much stress on the naturalness of his humanity, or, on the other hand, exaggerating his divinity to such an extent that his humanity was regarded as a mere act, which gave outsiders the wrong impression about his identity (specifically, by suggesting that he was not truly human).

Figure 2. The ministration of the midwives; the adoration of the Magi. Fresco attributed to the Master Trecentesco of Sacro Speco School, Monastero di San Benedetto, Subiaco (fourteenth century). By permission of Bridgeman Images.

Though it is difficult to sort out all the various cultural components that contributed to a given medieval representation of the Christ Child or the Virgin Mary, the following study of select religious texts dealing with these figures suggests that the apocryphal narratives, which earnestly explore the duality of Christ’s identity, had a significant influence upon other later medieval writers’ attempts at reconstructing Jesus’ hidden years. Originally composed in the Early Christian period, these legends were revived and elaborated in the high and later Middle Ages, when they appeared in new Latin redactions and in vernacular translations. With varying degrees of frequency, depending on the particular tale, these legends were also depicted in Western art, even though many of these legends were without any (or hardly any) biblical basis.

Artistic renderings of the apocryphal childhood of Jesus took a number of forms. Sometimes they helped fill out a sequence of images devoted to Christ’s childhood or were part of a cycle covering the span of Jesus’ life, thus providing a visual narrative paralleling the written accounts offered by devotional literature. Sometimes artistic scenes based upon the apocrypha were deftly mixed with more conventional images derived from Scripture, sometimes they themselves formed visual sequences depicting apocryphal legends. Artistically rendered in various ways, on the walls and ceilings of churches, as well as in Books of Hours and in illuminated manuscripts (occasionally as illustrations accompanying apocryphal texts), images of the apocryphal Jesus were viewed by both private and public audiences and were in no way limited to those who intentionally sought alternative Christologies.80 Some of the legends were loosely tied to Scripture (such as the story about the Child’s destruction of the idols in Egypt, which was linked with Isaiah 19:1). Legends that ended up being depicted very frequently acquired quasi-canonical status, such as the latter tale and the belief that an ox and an ass were present at the Christ Child’s manger. A number of apocryphal or legendary details crept into standard scenes, like the representation of the midwives who were summoned to assist Mary at Jesus’ birth and arrived belatedly. In artworks these women are often shown helping her with childcare, often by bathing the baby Jesus. They clearly have a central place in a fourteenth-century fresco of the Nativity in the monastery of the Sacro Speco: while one of these handmaidens prepares a bath, the other zealously extends her arms, reverently covered with a cloth, in order to receive the baby Jesus from his mother Mary (fig. 2). The cloth covering the woman’s hands and arms indicates her recognition of the divinity of the Child, whom she is privileged to attend.

In contrast, tales about the miracles that Christ supposedly worked as he was growing up, which were frowned upon by a number of medieval churchmen, were visually rendered much more rarely. In Chapter 3 I examine opposition to such legends on the part of the famous thirteenth-century Dominican theologian Thomas Aquinas. Despite the reasonableness of Aquinas’s arguments against Jesus’ childhood miracles, stories about them were nevertheless popular since they appealed to both lay and clerical audiences, who regarded such material as both entertaining and devotional. In addition to providing diversion for their audiences, such legends would have been welcomed as sources of information about the unknown period of Jesus’ youth, even if this material were only piecemeal or hypothetical.

Given the widespread popularity of such apocryphal stories, it is fair to suppose that late medieval writers were familiar with these accounts. The controversy surrounding the apocryphal legends may have actually drawn people’s attention to them, as well as impelled others to seek information from more reliable sources or to exercise their own creativity in dealing with Christ’s childhood. Chapter 4 considers the revelations of the fourteenth-century mystic Birgitta of Sweden concerning the Nativity and the family life of Jesus at Nazareth, some of which seem to respond to apocryphal traditions about Christ’s infancy and childhood (for example, by implicitly denying that midwives assisted Mary in attending to her newborn, a detail derived from early apocryphal narratives). Although this study could have focused on many other mystics from the later Middle Ages,81 I have chosen Birgitta since she provides an interesting perspective as a laywoman who gave birth to and cared for a number of children, and also because her revelations about the Virgin and Child are so numerous and frequently include the theme of Mary’s compassion, a common feature of late medieval piety. In addition, Birgitta was a popular saint throughout Europe and had a definite impact on late medieval English devotional culture, to which I give some priority in this study. Readers of this book who are interested in other mystics who had a special devotion to the Christ Child are invited to pursue some of my references and those of other scholars. Along similar lines, I do not explore representations of the child Jesus in a wide range of Middle English literary texts, but only mention (apart from the Middle English poems on Christ’s apocryphal childhood, which I examine in some detail) a sampling of Middle English works that deal with the beginning of Jesus’ life. These include a few Middle English lyrics, some late medieval biblical plays, and also Mandeville’s Travels. Elsewhere, I explore how Christ’s youth is handled in the well-known and highly regarded Middle English poem Piers Plowman, in which William Langland depicts the young Christ as a knight in training eager to fight against the devil in a tournament. By insisting on the Child’s having restrained himself from exercising his divine power for many years, and by exaggerating Jesus’ youthfulness at the wedding feast of Cana, Langland’s poem arguably addresses issues that are raised by the apocrypha.82

The interaction among the sources I examine in this book is complex, because we are not just dealing with the intertexuality of apocryphal and other written narratives; we must also consider the (in many cases mutual) influences wielded by oral tales, visual representations, and the popular traditions surrounding actual and imaginary places and objects. I move into less strictly textual domain in the latter part of Chapter 4, where I briefly deal with the legend that Mary made Jesus’ seamless tunic when he was still a boy and that it increased in size as he grew up. This legend was associated with a particular place, the Priory of Sainte-Marie in Argenteuil, which, from the middle of the twelfth century, claimed to have the relic of Jesus’ tunic. A distant yet important source for this legend was the apocryphal version of the Annunciation, which describes Mary as spinning thread when she conceived Jesus in her womb—a detail commonly depicted in Byzantine art.83 Since the notion of Mary as a textile worker was probably transmitted in multiple ways and also broadly reflects the social conditions of women in the pre-modern world, I would not venture to propose only one source—the apocrypha—for the legend that the Virgin made the seamless tunic at the beginning of Christ’s life. Nevertheless, the apocrypha clearly played a role in the spinning of this pious yarn, so to speak.84

On the whole, my study indicates that the apocryphal infancy legends were sources of both information and inspiration for writers (and artists) of the later medieval period. There were a variety of possible responses to the apocryphal material: some people apparently took these legends seriously, while others seem to have regarded them lightheartedly, or at least tolerated them as pious fiction. Still others—we may infer—tried to counteract them by offering alternative views of Jesus’ childhood. Even when they met with disapproval, the apocryphal legends had the effect of drawing attention to the vexed questions of whether Jesus behaved in a normal fashion during his boyhood and whether he developed gradually like other human children.85

The Appeal of Jesus—a Real Child Who Is Nonetheless Divine

As I have already suggested, one of the reasons why the Christ Child appealed to medieval Christians was that they perceived a surprising, inexplicable, and delightful conundrum resulting from God’s assumption of the form and characteristics of a little boy. Another ostensible reason was that, by becoming an infant and child, the deity became more approachable while still wielding a powerful influence upon people’s lives. The extremely popular Legenda aurea illustrates this principle in its chapter on Christmas, in which we hear that “a fallen woman, finally repenting of her sins, despaired of pardon. Thinking of the Last Judgment she considered herself worthy of hell; turning her mind to heaven she thought of herself as unclean; dwelling on the Lord’s passion, she knew she had been ungrateful. But then she thought to herself that children are more ready to be kind, so she appealed to Christ in the name of his childhood, and a voice told her that she had won forgiveness.”86 Although Christ of course passed beyond childhood during his life on earth, he was regarded as, somehow, a perpetual child in heaven who was always willing to grant forgiveness and offer his love.87 Bernard of Clairvaux went so far as to declare that “contact with [Jesus’] childhood is the only remedy for human sinfulness.”88 This presupposes that Christ’s childhood is still a reality and within reach, an idea that complements Jesus’ stipulation in the Bible that, in order to enter into heaven, one must embrace childhood (Matt. 18:3). The fourteenth-century Englishman Henry of Lancaster, in fact, explicitly claims that Jesus continues to be a child in heaven, because Christ is always ready to forgive.89 The underlying assumption that children are naturally forgiving (and, in a negative sense, inconstant, or—stated more neutrally—malleable in their interactions with other people) is reflected in a number of medieval sources. The thirteenth-century Franciscan encyclopedist Bartholomaeus Anglicus, for instance, notes (in the words of his fourteenth-century translator): “For mouynge of hete of fleisch and of humours þey ben eþeliche and sone wrooþ and sone iplesed and forȝeuen sone” (Because of the mobility of heat, of flesh, and of the humors, they are easily and quickly angered and readily pleased and quickly forgive).90 In the same chapter, which is devoted to the characteristics of children, Bartholomaeus explains, citing the (folk) etymology given by Isidore of Seville, that the Latin word for children (pueri) comes from the Latin adjective “purus” (“pure”). This attribute obviously refers to children’s sexual inactivity (their being pristine) and is grounded in the tenderness of their newly molded flesh, but it also seems to encompass their simplicity of character and light-heartedness.91 Describing children as pure also speaks to their mental and moral status, specifically the belief that young children are not yet capable of willingly choosing evil.92 In the aforesaid chapter on children, Bartholmaeus goes on to say that, before puberty, “children ben neisch of fleisch, lethy and pliant of body, abel and liȝt to meuynge, witty to lerne caroles, and wiþoute busines, and þey lede here lif wiþoute care and business…. And þey loven an appil more þan gold” (children are tender of flesh, flexible and malleable in body, agile and nimble for movement, keen to learn carols [or dances], and do not engage in serious tasks, and they lead their life without care and anxiety…. And they love an apple more than gold).93 Medieval adults’ desire to recover purity through repentance and spiritual cleansing and also to return, more generally, to the more carefree way of life exemplified by children (if not, more spiritually, to acquire a childlike trust and dependency on their divine Father),94 probably helps explain to a large extent the attraction that the child Jesus held for medieval Christians.95 Believers seem to have taken to heart Christ’s famous words: “unless you be converted, and become as little children, you shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven” (Matt. 18:3–4).

Nostalgia of an escapist sort, rather than a healthy desire for personal reformation, may sometimes have instilled the urge to find a lost childhood. More specifically, medieval Christians may have chosen to reflect upon Jesus’ childhood in order to ignore, at least temporarily, the negative aspects of their own lives or to avoid thinking about the suffering Jesus endured as an adult. In the Life of Blessed Margaret of Faenza (d. 1330), a Vallombrosan nun, we learn that she spent a good deal of time, “perfecting her meditations on the childhood of the Savior.” She experienced such “marvelously sweet things (mirabiles dulcedines) during them” that “she did not care to pass onto Christ’s later life (ad altiora conscendere, literally, “to climb to higher things”).”96 Perhaps feeling somewhat offended by the way she ignored his adulthood, Jesus finally told her that it was “not right to wish to taste only the honey and not the gall (de melle meo … & non de felle).” Margaret henceforth concentrated completely on the Passion, with great intensity, apparently exchanging all the honey for gall (though Christ’s rhyming of words suggests that sweetness and bitterness may go hand in hand). Other evidence suggests that at least some medieval people perceived a danger in fascination with Christ’s childhood. Once Humiliana de’ Cerchi (d. 1246), a Franciscan tertiary, was subjected to an illusion by the devil, who, “understanding her desires, showed her the figure of Our Lady and the child Jesus, radiant of face and raiment,” yet the pious widow saw through this demonic trick, which interestingly reveals the imaginative seductiveness, for some, of the Mother-and-Child duo.97

Although Christ had acquired the characteristics of ordinary children by the later Middle Ages,98 in contemporaneous sources he often seems distant and aloof, and occasionally imperious, so we would be wise to avoid the over-generalization that, at that time, the figure of a formidable Christ, such as the exacting Judge of the eerie Dies irae hymn, was completely superseded by the suffering Savior on the cross, as well as the gentle Child who is perpetually open to reconciliation.99 All three manifestations of the Son of God are in fact referred to—in quick succession, suggestive of a conflation—in a much earlier passage by St. Jerome, with which medieval scholars well read in patristic writings would have been familiar. Intending to convince his friend Heliodorus of the superiority of the anchoritic way of life, Jerome concludes his letter to him by reminding him that the God who will come to judge him and the whole human race is he who was a lowly man and a child who suffered during life, implying that Christ will show mercy to those who are likewise simple, humble, and patient.100 Given the many aspects of Christ’s persona—the different forms he assumes at the various stages of his earthly life, and in his current and future state of glory, forms which are able to coexist by virtue of his divinity—it is not surprising that medieval Christians imagined the child Jesus as a multifaceted and rather unpredictable personage. In an exemplum found in an early fifteenth-century collection of religious tales, “evidently compiled by a Franciscan in northern Italy,” the Christ Child (perhaps to be expected of one who is “purus”) is initially ill-disposed toward a prostitute who prays to him, but is then mollified by his merciful mother.101 In the famous early thirteenth-century collection of tales by the Cistercian Caesarius of Heisterbach, the Dialogus miraculorum, we learn, along similar lines, that the Christ Child turned his face away from a priest who presumed to consecrate the Eucharist unworthily.102 So the boy Jesus was not always imagined as a sweet and gentle child. He could express his displeasure in even more dramatic ways, as we have seen in an anecdote from the vita of Ida of Louvain, in which the Christ Child lashed out in a sort of temper tantrum at Ida’s sister, in defense of his beloved.

The Christ Child is, however, more often shown to be mysterious and elusive than retributive. In a didactic dialogue text transmitted in various medieval languages, the Child appears to the Emperor Hadrian; without at first identifying himself, he instructs the emperor in the central tenets of the Christian faith, and then disappears, immediately after revealing who he is.103 The Child likewise vanishes shortly after he appears to the boy Edmund of Abingdon (d. 1240), telling him that he was always beside him during his studies, and that he will continue to be with him.104 In his mystical dealings with the fourteenth-century Dominican nun Margaret Ebner, who cared for the infant Jesus as for a real child, Christ made a point of emphasizing his ability to leave her at will.105 In speaking of similar tales included in the so-called Sister Books that record the experiences and imaginary world of late medieval German nuns, Richard Kieckhefer remarks that “the theme of divine presence is expressed in these stories with something of the teasing playfulness associated with the Bridegroom in the Song of Songs.”106 While Kieckhefer’s comment is applicable in this more general discussion of the Child who often seems to be a flirtatious and inaccessible lover, I would stress the playful paradoxicality of a divine child who seems almost to play a game of “hide-and-seek” with his devotees.107 Along similar lines, in the vita of the Augustinian nun Clare of Montefalco by Berengario di Donadio, we learn that when she was still a child but had already entered the convent, the Virgin Mary appeared to her many times: “in her mantle the Virgin was [leading] the Child Jesus, who seemed to be the same age as Clare. Urged by his Mother, the Child Jesus [at times] approached Clare [on foot], took her hand, and filled her with wonderful consolations.” Yet Jesus made it clear to her that he was not accessible for play as she had assumed he would be, as someone her own age. “Seeing him thus with her own eyes, Clare wanted to take hold of him and play with him, but the Child eluded her and returned to his mother, leaving Clare in a state of deep desire.”108 Perhaps seeking to get at the ultimate untouchability of the child Jesus that stems from his divine majesty, an early fourteenth-century fresco based upon this episode depicts the young Clare kneeling before the child Jesus. Standing erect on his own two feet and partly sheltered by his mother’s mantle, the divine child blesses his young devotee (Master of St. Clare, Church of St. Clare, Chapel of the Holy Cross, Montefalco, c. 1333; fig. 3).