Читать книгу America's First Female Serial Killer - Mary Kay McBrayer - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

THE STAFF: BOSTON FEMALE ASYLUM, 1862

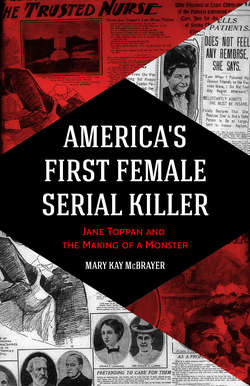

America’s first female serial killer was named Jane Toppan. She was born Honora Kelley.

Ten days after he dropped off his girls, he sewed his eyelids shut. We joked about it, despite its gore: how could you sew both eyelids shut? How could you see to stitch the second? This from women who call ourselves Christian. When he surrendered them, Mr. Kelley insisted their mother had died of consumption when Honora was in infancy. Honora remembers her mother anyway. But who can say if the memories of early childhood are of events or of stories so vivid we assume them to be true?

The wards heard the rumor about Mr. Kelley soon enough, and in the bunkroom after lights-out we once found them chanting around the girls’ beds in a circle. Delia was crying and yelling for them to stop, but Honora showed resilience. She smiled and tried to learn the words. She was only about six. We thought she didn’t understand what they were saying. When the wards saw us, they stayed in their circle because they thought we would confirm the rumor, and none of us said anything but to get themselves back to bed before they got the paddle. The tears ruddied Delia’s face and clung to the ends of her lashes as she begged us to tell her that wasn’t true about her da. Which we couldn’t do. Honora climbed into bed with her sister and put her forehead against Delia’s and whispered to her.

“Remember what he told us the last time he got angry, Delia. He promised it would be the last time. That he would go see Mam and take us with him before he saw it happen again. Remember? He only didn’t want to see it happen, see? It’s okay. He sewed them shut for us. So we could live here, with the nice ladies. So we could learn all these things and not die like Mam and be poor. See?”

Delia’s face went blank.

“The other girls don’t know it’s good that he did it. Wouldn’t the nice ladies tell us he hadn’t if it was bad? Wouldn’t they tell us? Wouldn’t they tell the girls it wasn’t true if it was bad?”

We never lie to them, of course. Although it would be easier to lie than tell the orphans the truths of their still-living relatives. Peter Kelley disappeared, with eyes sewn shut or wide open we didn’t know, so for Honora and Delia, there was no decision to make. If you don’t know the truth, there is nothing that is not true. We only just got the other girls back to bed. Honora seemed totally unfazed.

She does tell stories, but they are not exactly lies. Her eyes go so black they absorb light as she channels stories that no child could invent. Her chubby work-worn hands gesture to embellish the tales. Of her father colonizing India wearing tan clothes and a hat so hard she could stand on it without hurting it. Of the brown-skinned boy her father will bring her to marry when he stops back in Boston to retrieve her. Of how she and Delia, their two elder sisters, their living grandfather, and their mother will all return to Ireland once the adults get their affairs sorted. Of her mother dining in Kensington Palace at Queen Victoria’s table, not as a servant, but as a guest, an ambassador to both Ireland and India.

Her parents’ whereabouts are unknown. We have no knowledge of the elder sisters. After a few weeks, we could even doubt that Delia was related to Honora. Delia is a few years older, though we don’t know how many, and her face is so much fairer, her hair so much thinner, here eyes so light and luminous one wonders if she can see anything at all, if she doesn’t just sees through everything. Her mind wanders, and we often find her having conversations with no one in the stairwells. It is easy to forget that those girls were associated at all.

All the girls in the asylum love her, too young and so eager to believe her to notice the fantasies’ inconsistencies. Honora always stands amid a gaggle of admirers once her chores are finished—and although this isn’t often, there is never an open moment when she is alone. She gives them hope. False hope, but hope nonetheless. It seems harmless.

The women at Boston Female Asylum love Honora, too. We even gave her the nickname Nora. No matter what the task, she works at it till it is completed and satisfactory. True, her calling us to observe her progress grows tiresome, but with just a little praise, she will do anything, even to the point of asking for more chores. If one of us arrives to admire her work, she is the happiest girl. She takes on chores no other girls want to do, which makes them all like her even more.

Only once, when one of the new staff chastised her for needing constant approval, did Honora behave badly, spreading slander about one of the older orphans which we then toiled to dispel and diminish. We should not tell you what she said, as that would only perpetuate the lie—and this was a lie, no probability of trueness, just a childish vendetta to scare the other wards from being friends with the girl. Nora was punished with the paddle, but she seemed to learn her lesson about the importance of a girl’s reputation. After one of us consoled her, she returned to her chores, and by the end of the day, she was back to her normal garrulous self. That’s all we know about her.

Nora is a hardworking girl. She will be a blessing to anyone’s home.