Читать книгу The Other Mrs - Mary Kubica - Страница 17

SADIE

ОглавлениеTwo times I circle the house. I make sure all the doors and windows are locked. I do it once, and then, because I can’t be sure I got them all, I do it again. I pull the blinds, the curtains closed, wondering if it would be prudent to have a security system installed in the home.

This evening, as promised, Will drove Imogen to the public safety building to speak with Officer Berg. I hoped Will would come home with news about the murder—something to settle me—but there was nothing to report. The police weren’t any closer to solving the crime. I’ve seen statistics on murders. Something like one-third or more of murders become cold case files, leaving police departments mired in unsolved crimes. It’s an epidemic.

The number of murderers walking among us every day is frightening.

They can be anywhere and we’d never know.

According to Will, Imogen had nothing to offer Officer Berg about last night. She was asleep, as I knew she’d been. When asked if she’d seen anything out of the ordinary over the last few weeks, she turned stiff and gray and said, “My mom hanging from the end of a fucking noose.” Officer Berg had no more questions for her after that.

As I contemplate a third go-round of the windows and doors, Will calls to me from the top of the stairs, asks if I’m coming to bed anytime soon. I tell him yes, I’m coming, as I give the front door a final tug. I leave on a living room lamp to give the pretense we’re awake.

I climb the stairs and settle into bed beside Will. But I can’t sleep. All night, I find myself lying in bed, thinking about what Officer Berg said, how the little Baines girl was the one to find Morgan dead. I wonder how well Tate knows this little girl. Tate and she are in class together, but that doesn’t mean they’re friends.

I find that I’m unable to shake from my mind the image of the six-year-old girl standing over her mother’s lifeless body. I wonder if she was scared. If she screamed. If the killer lurked nearby, getting off on the sound of her scream. I wonder how long she waited for the ambulance to arrive, and if, in that time, she feared for her own life. I think of her, alone, finding her mother dead in the same way that Imogen found her own mother dead. Not the same, no. Suicide and murder are two very different things. But still, it’s unfathomable for me to think what these girls have seen in their short lives.

Beside me, Will sleeps like a rock. But not me. Because as I lie there unsleeping I start to wonder if the killer is still on the island with us, or if he’s gone by now.

I slip from bed at the thought of it, my heart gaining speed. I have to be sure the kids are okay. The dogs, on their own beds in the corner of the room, take note and follow along. I tell them to hush as Will rolls over in bed, pulling the sheet with him.

On the wooden floors, my bare feet are cold. But it’s too dark to feel around for slippers. I leave them behind. I step out of the bedroom, moving down the narrow hall.

I go to Tate’s room first. There, in the doorway, I pause. Tate sleeps with the bedroom door open, a night-light plugged in to keep monsters at bay. His small body is set in the middle of the bed, a stuffed Chihuahua held tightly between his arms. Peacefully he sleeps, his own dreams uninterrupted by thoughts of murder and death, unlike mine. I wonder what he dreams of. Maybe puppy dogs and ice cream.

I wonder what Tate knows of death. I wonder what I knew of death when I was seven years old, if I knew much of anything.

I move on to Otto’s room. There’s a roof outside Otto’s window, a single-story slate roof that hangs over the front porch. A series of climbable columns hold it upright. Getting in or out wouldn’t be such a difficult task in the middle of the night.

My feet instinctively pick up pace as I cross the hall, telling myself Otto is safe, that certainly an intruder wouldn’t climb to the second floor to get in. But in that moment, I can’t be so sure. I turn the handle and press the door silently open, terrified of what I’ll find on the other side. The window open, the bed empty. But it’s not the case. Otto is here. Otto is fine.

I stand in the doorway, watching for a while. I take a step closer for a better look, holding my breath so I don’t wake him. He looks peaceful, though his blanket has been kicked to the end of the bed and his pillow tossed to the floor. His head lies flat on the mattress. I reach for the blanket and draw it over him, remembering when he was young and would ask me to sleep with him. When I did, he’d toss a heavy arm across my neck and hold me that way, not letting go the entire night. He’s grown up too fast. I wish for it back.

I go to Imogen’s room next. I set my hand on the handle and sluggishly turn, careful not to make any noise. But the handle doesn’t turn. The door is locked from the inside. I can’t check on her.

I turn away from the door and inch down the stairs. The dogs follow on my heels, but I move far too slowly for their liking. At some point, they bypass me and dash down the rest of the steps, cutting through the foyer for the back door. Their nails click-clack on the wooden floors like typewriter keys.

I pause before the front door and glance out the sidelight window. From this angle, I catch a glimpse of the Baineses’ house. There’s activity going on even at this late hour. Light floods the inside of it, a handful of people milling about inside. Police on a quest. I wonder what they’ll find.

The dogs whine at me from the kitchen, stealing my attention away from the window. They want to go outside. I follow them, opening the sliding glass door, and they go rushing out. They make a beeline for the corner of the yard, where they’ve recently begun digging divots in the grass. The incessant digging has become their latest compulsion and also my pet peeve. I clap my hands together to get them to stop.

I brew myself a cup of tea and sit down at the kitchen table. I look around for things to do. There’s no point in going back to bed because I know I won’t sleep. There’s nothing worse than lying in bed, restless, worrying about things I can’t do anything about.

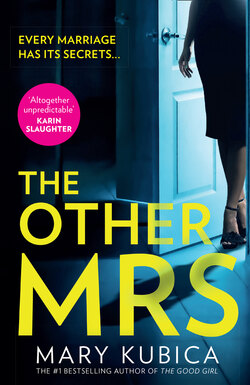

On the edge of the table sits a book Will has been reading, a true crime novel with a bookmark thrust in the center of it.

I take the book into the living room, turn on a lamp and settle myself on Alice’s marigold sofa to read. I spread an afghan over my lap. I open the book. By accident Will’s bookmark comes tumbling out, falling to the floor beside my feet.

“Shit,” I say, reaching down for the bookmark, feeling guilty that I’ve lost Will’s page.

But the guilt only lasts so long before it’s replaced with something else. Jealousy? Anger? Empathy? Or maybe surprise. Because the bookmark isn’t the only thing that’s fallen out of the pages of the book. Because there’s also a photo of Erin, Will’s first fiancée, the woman he was supposed to marry instead of me.

My gasp is audible. My hand comes to a stop inches above her face, my heart hastening.

Why is Will hiding a photograph of Erin inside this book? Why does Will still have this photograph at all?

The photo is old, twenty years maybe. Erin looks to be about eighteen or nineteen in it. Her hair is wild, her smile carefree. I stare at the picture, into Erin’s eyes. There’s a pang of jealousy because of how beautiful she is. How magnetic.

But how can I be jealous of a woman who is dead?

Will and I had been dating for over a month before he mentioned her name. We were still in that completely smitten stage, when everything felt noteworthy and important. We’d talk on the phone for hours. I didn’t have much to say about my past, and so, instead, I told him about my future, about all the things I planned to one day do. Will’s future was undecided when we met, and so he told me about his past. About his childhood dog. About his stepfather’s diagnosis with cancer, the fact that his mother has been married three times. And he told me about Erin, the woman he was supposed to marry, a woman he was engaged to for months before she died. Will cried openly when he told me about her. He held nothing back, and I loved him for it because of his great capacity to love.

In all my life, I didn’t think I’d ever seen a grown man cry.

At the time, the sadness of Will losing a fiancée only attracted me to him more. Will was broken, like a butterfly without wings. I wanted to be the one to heal him.

It’s been years since her name has come up. It’s not as if we talk about her. But every now and then another Erin is mentioned and it gives us pause. The name alone carries so much weight. But why Will would dig this photograph out of God knows where and carry it around with him is beyond me. Why now, after all this time?

My hand grazes the photograph but I don’t have it in me to pick it up. Not yet. I’ve only seen one other photograph of Erin before, one that Will showed to me years ago at my request. He didn’t want to, but I insisted. I wanted to know what she looked like. When I asked to see a picture, he showed me with circumspection. He wasn’t sure how I’d react. I tried to be poker-faced about it, but there was no denying the sharp pains I felt inside. She was breathtaking.

I knew in that instant: Will only loved me because she was gone. I was his second pick.

I brush my finger against Erin’s fair skin now. I can’t be jealous. I simply can’t. And I can’t be mad. It would be insensitive of me to ask him to throw it away. But here I am, after all these years, feeling like I’m playing second fiddle to the memory of a woman who’s dead.

I reach for the photo and hold it in my hand this time. I won’t let myself be a coward. I stare at her. There’s something so childish about her face, so audacious and raw, that I feel the greatest need to scold her for whatever it is she’s thinking as she makes a pouty face at the camera, one that is as provocative as it is bold.

I jam the picture and the bookmark somewhere back inside the book, rise from the sofa and bring the book to the kitchen table. I leave it there, having suddenly lost the desire to read.

The dogs have begun to bark. I can’t leave them outside barking in the middle of the night. I open the slider and call to them, but they don’t come.

I’m forced outside into the backyard to get their attention. The patio is freezing cold on my bare feet. But that discomfort is secondary to what I feel inside as I get taken in, swallowed by the darkness. The kitchen light fades quickly behind me as the December night closes in.

I can see nothing. If someone was there, standing in the darkness of our yard, I wouldn’t know. An unwanted thought comes pummeling into me then. My saliva catches in my throat and I choke.

Dogs have adaptations that people don’t have. They can see much better than humans in the dark. It makes me wonder what the dogs see that I can’t see, what they’re barking at.

I hiss out into the night, calling quietly for the girls. It’s the middle of the night; I don’t want to shout. But I’m too scared to go any farther outside than I already am.

How do I know that Morgan Baines’s killer isn’t there?

How do I know that the dogs aren’t barking because there’s a murderer in my yard?

Backlit by the kitchen light, I’m a fish in a fishbowl.

I can see nothing. But whoever is there—if anyone is there—can easily see me.

Without thinking it through, I take a step suddenly back. The fear is overwhelming. There’s the greatest need to run back into the kitchen, close and lock the door behind myself, pull the drapes shut. But would the dogs be able to fend off a killer all on their own?

And then the dogs suddenly stop their barking and I’m not sure what terrifies me more, the barking or the silence.

My heart pounds harder. My skin prickles, a tingling sensation that runs up and down my arms. My imagination goes wild, wondering what horrible thing is standing in my yard.

I can’t stand here waiting to find out. I clap my hands, call to the dogs again. I hurry inside for their biscuits and shake the box frantically. This time, by the grace of God, they come. I open the box, spill a half dozen treats on the kitchen floor before closing and locking the slider, pulling the drapes tightly closed.

Back upstairs, I check again on the boys. They’re just as I left them.

But Imogen’s door, this time as I pass by, is open an inch. It’s no longer closed. It’s no longer locked. The hallway is narrow and dark with just enough light that I’m not blind. A faint glow from the lamp in the living room rises up to me. It helps me see.

My eyes go to that one-inch gap between Imogen’s door and the frame. It wasn’t like that the last time I was here. Imogen’s room, like Otto’s, faces onto the street. I go to her door and press on it, easing it open another inch or two, just enough so that I can see inside. She’s lying there, on her bed, with her back to me. If she’s faking sleep, she does so quite well. Her breathing is rhythmic and deep. I see the rise and fall of the sheet. Her curtains are open, moonlight streaming into the room. The window, like the door, is open an inch. The room is icy cold, but I don’t risk stepping inside to close it.

Back in our bedroom, I shake Will awake. I won’t tell Will about Imogen because there’s nothing really to say. For all I know, she was up using the bathroom. She got hot and opened her window. These are not crimes, though other questions nag at the back of my mind.

Why didn’t I hear a toilet flush?

Why didn’t I notice the chill from the bedroom the first time I passed by?

“What is it? What’s wrong?” Will asks, half-asleep.

As he rubs at his eyes, I say, “I think there’s something in the backyard.”

“Like what?” he asks, clearing his throat, his eyes drowsy and his voice heavy with sleep.

I wait a beat before I tell him. “I don’t know,” I say, leaning into him as I say it. “Maybe a person.”

“A person?” Will asks, sitting quickly upright, and I tell him about what just happened, how there was something—or someone—in the backyard that spooked the dogs. My voice is tremulous when I speak. Will notices. “Did you see a person?” he asks, but I tell him no, that I didn’t see anything at all. That I only knew something was there. A gut instinct.

Will says compassionately, his hand reassuringly stroking mine, “You’re really shaken up about it, aren’t you?”

He wraps both hands around mine, feeling the way they tremble in his. I tell him that I am. I think that he’s going to get out of bed and go see for himself if there’s someone in our backyard. But instead he makes me second-guess myself. It isn’t intentional and he isn’t trying to patronize me. Rather, he’s the voice of reason as he asks, “But what about a coyote? A raccoon or a skunk? Are you sure it wasn’t just some animals that got the dogs worked up?”

It sounds so simple, so obvious as he says it. I wonder if he’s right. It would explain why the dogs were so upset. Perhaps they sniffed out some wildlife roaming around our backyard. They’re hunters. Naturally they would have wanted to get at whatever was there. It’s the far more logical thing to believe than that there was a killer traipsing through our backyard. What would a killer want with us?

I shrug in the darkness. “Maybe,” I say, feeling foolish, but not entirely so. There was a murder just across the street from us last night and the murderer hasn’t been found. It’s not so irrational to believe he’s still nearby.

Will tells me obligingly, “We could mention it to Officer Berg anyway in the morning. Ask him to look into it. If nothing else, ask if coyotes are a problem around here. It would be good to know anyway, to make sure we keep an eye on the dogs.”

I feel grateful he humors me. But I tell him no. “I’m sure you’re right,” I say, crawling back into bed beside him, knowing I still won’t sleep. “It probably was a coyote. I’m sorry I woke you. Go back to bed,” I say, and he does, wrapping a heavy arm around me, protecting me from whatever lies on the other side of our door.