Читать книгу The Life and Times of Mary Ann McCracken, 1770–1866 - Mary McNeill - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNEW FOREWORD

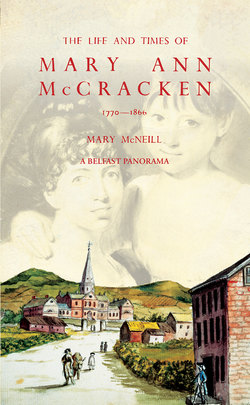

First published in 1960, The Life and Times of Mary Ann McCracken is a biography written by one remarkable Belfast woman about another. The decade of the 1950s was a hopeful time in Belfast, much as it had been when Mary Ann McCracken was young in the 1790s. People were emerging from enduring wartime rationing and undoubtedly, the terrible experience of World War II and the blitz of Belfast had brought people together. They were the first generation to benefit from the welfare state and although there had been a rumbling IRA border campaign, it impacted little on Belfast and would soon terminate from lack of support.

The 1780s and 1790s had likewise been a time for optimism. Belfast was leading the country in advanced social and political thinking, culminating in the formation of the Society of United Irishmen in the town in 1791. The young Mary Ann McCracken proved herself just as radical a thinker as them, holding her own in advanced political debate and associating with some of the most influential of the United Irishmen, including her own brother Henry Joy McCracken and the legendary Thomas Russell. Anti-slavery, the good of the common man, Catholic emancipation, improving the position of women, Irish music and language, the study of the natural world all occupied her and them as much as the enthusiasm for the French Revolution and advanced political reform for which they are better known. The real strength of Mary McNeill’s book is that she allowed Mary Ann to speak for herself through her extensive correspondence. Those letters provide a remarkable insight into a very special period in Belfast’s history and she lived long enough to pass them on to the nineteenth-century historian of the United Irishmen, R.R. Madden, and through him into the archives of Trinity College Dublin. They were a fundamental part of my own research into the 1790s, much as they have been to successive generations of historians.

Mary Ann was born into a middle-class Presbyterian family which already had a reputation for civic leadership and reformist leanings. Her maternal grandfather, Francis Joy, founded the first Belfast newspaper, the Belfast News-Letter, in 1737, which was a channel for reformist opinion until it became an organ of government under new ownership after 1795. The Joys were also among some of the earliest members of the Belfast Charitable Society, founded in 1752, who designed and built Clifton House which opened in 1774 as Belfast’s first institution to care for the poor – a mission which it strongly maintains in regard to a wide range of social need today. Mary Ann was to continue involvement in its work until her death in 1866, aged 96. The McCrackens and Joys were pioneering textile manufacturers, laying the foundation of Belfast’s industrial heritage. Aged only 22, Mary was to set up her own muslin business with her sister, and with the other McCrackens was a noted philanthropic employer. She thought it an employer’s duty to create time for the workers to pursue leisure and education, and later created programmes for educating the female poor.

It was this reputation as a friend of the poor which made Henry Joy McCracken a very unusual leader of the 1798 Rebellion. Working people, Protestant and Catholic alike, rallied to him even after that curse of modern Irish History, sectarianism, was tearing former allies apart and would soon infect Belfast’s future in a way that it had not done in the eighteenth century. The account of Mary Ann’s trek through the soldier and rebel-infested hills of Belfast in search of her brother after his defeat at the Battle of Antrim is only one example of the actions of this fearless young woman. And her correspondence during the imprisonment, trials and public executions of the two young men dearest to her, Henry Joy in 1798 and Thomas Russell in 1803, movingly describes the disintegration of the ideals and hope which had so marked preceding decades.

Another remarkable Belfast woman and contemporary of Mary Ann’s – William Drennan’s sister, Martha McTier – commented after the bloodbath of 1798 and the sectarian reprisals which continued after it: ‘It will be long before this devoted country recovers’. Mary Ann’s nineteenth-century correspondence reflects that negative change. Here post-union Ulster is a much more restrictive society, particularly for women.

It is easy to romanticise the 1790s – long seen as one of the great might-have-beens of Irish history. Even so, it is a period when Belfast was celebrated as Ireland’s capital of enlightened thinking and even today it commands interest and respect from people of very different political and religious leanings. There is something very symbolic in the Belfast Charitable Society reproducing this impressive book in its 267th anniversary year, for it has continued unbroken that philanthropic mission of the Joys, the McCrackens and the other Belfast reformers of the eighteenth century.

Marianne Elliott

September 2019