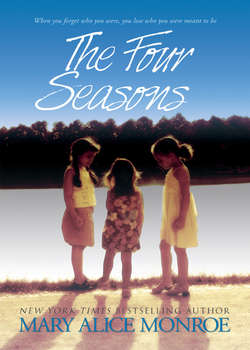

Читать книгу The Four Seasons - Мэри Монро, Мэри Элис Монро, Mary Monroe Alice - Страница 13

7

ОглавлениеJanuary 5, 1973

JILLY WAS SEVENTEEN AND pregnant. She rode in the passenger seat of the black Cadillac Brougham, resting one hand on her gently rounded belly and looking out at the dull, monotonous scenery of Interstate 95 north to upper Wisconsin. The morning was bright and sunny, mocking the dark, brooding mood within the car.

“Do you need to stop?” Her father kept his eyes on the road. In the past four hours he’d offered little conversation besides brief inquiries as to whether she was hungry or had to use the rest facilities. He wasn’t the talkative type on the best of occasions, and rarely carried on the usual father-daughter banter about such things as school grades, boyfriends or plans for college. The silence today, however, was punitive.

“No,” she replied, glancing at his stern profile. She felt herself recoil and wanted to weep. “Thank you. I’m okay.” She turned away again, tightening her bladder muscles against the straining urge. She would not ask to stop again so soon after his pithy comment on how this trip was taking forever due to pit stops. She could kick herself for having that soda.

Despite the long drive, her father maintained his usual crisp and immaculate appearance in his dark suit and pressed white shirt. Next to him she felt like a ragamuffin in a baggy dress and her mother’s old coat. The blue wool wasn’t warm enough for the January cold, but the voluminous A-line style was the only one they had that allowed for Jilly’s expanding waistline. What did it matter what she looked like or how warm it was, she told herself. She didn’t plan on going outside much in the next few months so she would make do with her mother’s hand-me-down.

She sighed and looked again at the raw bleakness outside her window, feeling each of the miles that separated her from her home and the life she once knew in Illinois, from the carefree high school girl she once was.

Jilly knew she’d crossed the line from child to woman ever since that evening last November when she walked into her parents’ bedroom, closed the door behind her and quietly told her parents that she was pregnant.

Her mother had accepted the news with her usual hysteria.

“Oh, my God! Pregnant? Oh, my God. You must have been drinking. You were, weren’t you?” she accused, sitting up in bed and pointing. She’d been watching TV and her heavy lids, the slurred words and the telltale empty glass on her bedside table revealed she’d been drinking. “I told you she was drinking,” she’d screeched to her husband, as if it was his fault.

“Mom, I wasn’t drinking.”

“How could you have done this to us? I knew you’re irresponsible, you’ve always been. But I didn’t know you were immoral, too! It’s a mortal sin what you’ve done. A mortal sin! And the scandal! Your father is a judge in this city. Did you think about him? Did you think about anyone but yourself?”

Her mother cried then, not for Jilly, but for herself. “Oh, Bill, I can’t take this. Two daughters ruined.” Then turning back to Jilly she narrowed her eyes and cried, “Your sisters’ reputations will be ruined, too. And so will mine!”

Her father compressed his lips and didn’t say a word. His thick red brows, streaked with white, furrowed as he slowly closed his magazine and let it drop to the floor.

Jilly turned her eyes to the ground, embarrassed and ashamed for bringing such scandal to the family. Everyone knew that “good” girls didn’t go all the way. “Good” girls did not get pregnant. Standing there at the foot of their bed, she looked in her parents’ eyes and a part of her died seeing the judgment written there: Jillian Season was not a Good Girl.

After a short but noisy cry her mother sobered up and spent a while in the bathroom. Jilly glanced at her father to see him staring at her, an odd expression on his face, as though he couldn’t quite believe what he was hearing. How many times had they argued about her curfew in the past? He’d always told her it wasn’t that he didn’t trust her, he didn’t trust the boys she dated.

“Well, when is the baby due?” her mother asked when she emerged from the bathroom. She had washed her face, brushed her short red-gold hair, and she appeared to have collected her composure. Jilly took heart that they’d have a real conversation instead of histrionics, but her hope wobbled as her mother crossed the room and climbed back into the bed.

Jilly remained standing. “In early May sometime.”

“Have you seen a doctor? Really, Jilly, how do you know you’re pregnant?”

“I went to Planned Parenthood.”

“Good God,” her mother exclaimed. “That place?” As far as she was concerned, Planned Parenthood’s clinic, located in a poor, dangerous part of town, was a bastion of fanatics—enemies of the Church who offered birth control and abortions to a new, immoral generation that preached free love. And now her daughter was one of them. “Bill…” she said, reaching over to clasp his hand in a dramatic gesture.

“We’ll send her to Dr. Applebee,” he said, the voice of reason. “Then we’ll get the facts.”

“I am pregnant. Three months pregnant. I had a blood test and there’s no mistake.”

The calm authority in her voice, the very fact that she had found her way to Planned Parenthood, had the test done and could report to them this finding, all without their help, took them both by surprise. She could see them look at her differently, more as an adult.

“Who is the father?” her own father asked.

“I don’t want to say,” she replied, looking away.

“Don’t press her just yet,” her mother intervened. “I’m sure she hasn’t gotten used to the idea. I certainly couldn’t believe it when I found out I was having you. I was married, of course,” she said, letting Jilly know that this shift of attitude by no means forgave her. “But was I surprised. Stunned, in fact. I had to give up my dancing career.”

Jilly knew the worst was over once Mother’s dancing career was mentioned. Her mother cherished her years in the Chicago Ballet Company as the highlight of her life and she never let an opportunity go by when she couldn’t remind them of all she’d given up for her family.

Once the idea of her pregnancy sunk in, the horror and shock subsided and the concept that they would be grandparents began to take root. Their voices grew solicitous. They painted rosier scenarios. Her parents assumed that she had a special beau, someone she was in love with and wanted to protect. She felt like dirt under their feet as she stood there listening while they calmed down and began talking about how they’d help her—and him—through this ordeal. Abortion was briefly mentioned in an academic sense, but they were Catholic. It wasn’t really an option.

The kindness was killing her. It was easier when they were mad and yelling at her. At least then she could shut down emotionally. As it was, the guilt was paralyzing.