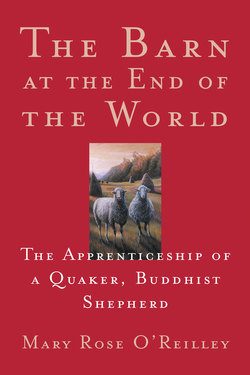

Читать книгу The Barn at the End of the World - Mary Rose O'Reilley - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCatching and Flipping and Shearing

FLIPPING SHEEP is a major component of barn management. You have to flip them to shear them, to perform any vet work (as we call the inoculations and small surgeries of everyday work), or merely to get their attention and remind them that they’re sheep and we aren’t. Perhaps I should mention what everybody takes for granted: you have to catch them first.

When I say “lambs,” most people think about cute little wooly animals, but in our barn we are moving market lambs and wethers, big castrated male sheep that run two hundred pounds. We also have around a hundred ewes at the moment, our breeding females, and several huge ram sires. Catching any of these animals requires skill and strength.

“Don’t you use a crook?” my friends ask, picturing perhaps a quaint shepherdess on an embroidered field of wildflowers. We don’t, but I don’t know why we don’t. Maybe it’s considered effeminate. Ben, of course, can easily head a sheep out of the flock, grab it under the chin, and get a purchase with the other hand on its tailbone. For my part, I’m slow, a little arthritic, and like to save my hands for sawing pitifully on the violin. I can’t reach from the chin to the tail of a large animal. Mostly I slide around in sheep shit to the delight of anyone in the barn.

“Don’t run around so aimlessly,” Ben sings out, as we pull sheep in for shearing. I’m black and blue all over. My instinct is to sink my fingers into the wool and hold on, at which point the rams just gather steam and pull me over.

We shear constantly, for one reason or another, in the summer simply to keep the animals cool. Our Polypays and Hampshires produce a poor wool staple, so we don’t bother with the classy shearing that might be done for the handspinning trade. Sheared wool is, however, separated by color, bagged, and sold for mattress-stuffing and blankets.

The rules of shearing are (1) keep the skin stretched; (2) don’t cut off the teats or nick a ewe’s vagina or cut off a ram’s sheath; (3) watch out for the Achilles tendon; and (4) hold the clippers flat and clip close. In my first few attempts I did not cut close but neither did I excise any vital organs.

While we shear, Ben, the extrovert, tells me more than I can absorb about genetics, breed characteristics, and the gossip of sheep production: which breeders are well thought of, who are suspected of having “spider” (a genetic malformation) in the DNA of their animals. Much of it goes right by me. At this point, I can authoritatively pick out a Dorset from a Hampshire, but a “classic Texel look” is lost on me. I’m merely happy I’ve reached a point where not all sheep look alike.

But as the summer days go by, I’m growing discouraged. My bones ache; my mind throbs and misfires over calculations about feed ratios. I wonder if I am too old to take this new direction, or if, like so many things, it’s a matter of focus rather than of strength and agility.