Читать книгу The Consummate Canadian - Mary Willan Mason - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4 HIS EARLY YEARS OF PRACTICE

EVEN BEFORE HE WAS CALLED TO THE BAR, SAM HAD BEEN EMPLOYED in the firm of Ivey and Ivey in London. One of the first cases he worked on, an appeal case concerning H.J. Garson and Co., the plaintiff, versus Empire Manufacturing Co. Ltd., defendant, involved alleged short weights and dirty metals. In the Supreme Court of Ontario Ivey and Ivey acted for the defendant. The appeal was dismissed with costs by the plaintiff to the defendant. The case was heard before the Chief Justice of the Exchequer, Sir William Mulock, and Messrs. Justice Riddell, Sutherland, and Masten. Sam was well pleased to have helped with the presentation of the case and kept everything related to it in a special file.

In 1921, he wrote to the External Registrar, University of London, South Kensington:

“Dear Sir: I am in receipt of the pamphlet containing the Regulations relating to degrees in Laws for external students and after reading the notes upon State 116, I am in doubt about my manner of admission.

I am not a graduate in arts of any university, but I am a graduate of Osgoode Hall (Ontario Law School Toronto) where I received the degree of Barrister-at-Law before being called to the Bar. Does this entitle me to admission of your law examinations? I am exceedingly anxious to write for the LL B (honours) but cannot go to London for your matriculation examinations. I, of course, have an honour certificate of matriculation into the Ontario universities and have standing in several subjects equivalent to the first year of our universities (Toronto and McGill). I can give references as to my fitness and would point out that I have received scholarships at Osgoode Hall.”

There is no record of a reply. For many years an LL.B. to put after his name was to become a consuming passion. Later Sam would pull many strings in his quest to be awarded an LL.D., but to no avail.

In August of 1922, Sam registered with the University of Chicago for eight departmental examinations, all approved for those whose practice would be in Ontario. However he never enrolled. More than likely he found the load he was bearing at Ivey and Ivey too time and energy consuming to do justice to eight subjects of study. His object was to enrol in Law School in Chicago or to acquire an A.B. He would have been given one year of credit for “Home Study,” but the remaining three years would have had to be spent on campus in Chicago, a dream that had to be put on hold for lack of money and which was never fulfilled. He had hoped to be given all four years in “Home Study,” but that was impossible.

In the early twenties the firm became known as Ivey, Elliott and Ivey and later Ivey, Elliott, Weir & Gillanders. By 1923, the firm name was listed as Ivey & Co., in 1924 as Jeffery & Co. By 1925 it had reverted to Ivey & Co, in 1926 Jeffery & Co once more. In 1927, the practice was listed as Jeffery, Gelber, A.O. McElheran & E.G. Moorhouse. Ten years later in 1937, Sam was in business for himself.

In the early years of his practice, Sam would be involved in a bankruptcy suit brought by London Life Insurance Co. against Lang Shirt of London. A complicated series of actions began after the president of the company was found to have borrowed on his own life insurance policies from Aetna Life Insurance Co. in order to benefit Lang Shirt. When the bankruptcy of the shirt manufacturer loomed, the president took his own life. Sam helped to prepare briefs on the case which lasted over a period of years.

As soon as Sam started out as a young lawyer with Ivey and Ivey, he began to buy bonds and stocks with whatever bits of money he could spare. With memories of his father’s ineptitude in the management of money, taxes in arrears, the sale of property for realty taxes and bought back later with a penalty, in arrears again, then having to move, Sam was determined that his goal was to be solvent and debt free.

At some time in 1920 or possibly 1921, an entirely unplanned encounter did a great deal to change Sam’s life. An itinerant picture salesman called on him at his office, showed him Dame Laura Knight’s watercolour Ballet Girls and Sam fell under its spell. Forty five years later in a letter to L.A. Dowsett of Leger Galleries in Bond Street, Sam wrote:

“I was got into the art collecting by Laura Knight. A man named Carroll who used to travel pictures through Canada and the United States landed a watercolour on me which had been done by Laura Knight for reproduction in a magazine. It was of ballet girls.”

This uncharacteristic purchase marked a real change for him from the usual stocks and bonds. Acquiring something which appealed to him aesthetically and which was just to be hung on a wall to be admired gave him enormous pleasure. He was fascinated and, as time went on, collecting paintings and objects of distinction and beauty which caught his fancy and gave him delight competed with his compulsion to amass a fortune through an investment portfolio.

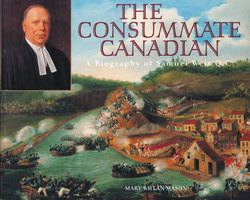

Samuel Edward Weir of London, Ontario, at the outset of his career in the early 1920s.

An early client, E.V. Harmon, who lived in the East Twenties, the Gramercy Park area of New York City, was landlord to over thirty properties in London. Sam looked after Harmon’s holdings, an example to him early in his career of the advantage in handling other’s finances as well as the advantages of being a landlord himself. On behalf of another client, Ben Baldwin, the young Sam travelled to Holyoke, Massachusetts more than once in order to effect the sale of a service station. A business and personal friendship began with Baldwin senior and his two sons, Bill and Bentley, that lasted for many years. Sam also acted for the W.R. Kent estate which was comprised of an impressive number of real estate properties stretching from Montreal to Manitoba and which was not wound up finally until 1937. Payments to Sam for handling these properties seemed rather sporadic, but eventually he was paid handsomely for his ministrations and he began to appreciate the possibilities of an international practice. Such early experiences whetted his appetite and expanded his horizons far beyond London, Ontario.

Ruth, now retired from the American Red Cross, and Wilbur Howell lived in Lower Manhattan on Washington Square with a kitten, Nicu, an offspring of Sarah’s cat. In one of the many letters to Sarah, Ruth recommends romaine and Simpson lettuces as well as asparagus, common enough perhaps in New York shops of the time but rare and pricey for the Weirs. Martha Amanda, now widowed for the third time, divided her days between her two daughters, Sarah and Eva, both living in Ontario. Her visits to Sarah’s household were rather dreaded if inevitable events.

In the summer of 1921, Sarah wrote to Ruth that a cow has freshened and that she is so very weary. “Why house clean?” asked Ruth in reply, “Let it go,” — not advice to be followed easily by a woman of Sarah’s pride. Sarah apparently had complained of eczema and Ruth commented that she doubted that diet had much to do with it. Sarah wrote that Martha’s hand pained so she bound live fish worms around it. The source of this bit of medical advice is not divulged and neither is the opinion of George M.D. nor of Ruth R.N.

About this time Paul was packed off to visit his sister briefly and Ruth accompanied him back to London. In the early years of her marriage Ruth spent a part of the summers in her old London home. A little weakness from her bout of malaria in Rumania still remained and, now having been diagnosed as having high blood pressure, London was a welcome respite from the heat of New York City. Ruth’s letters to Wilbur give a picture of Sam busily tending to his delphiniums and watering the lawn, Paul doing odd jobs for the neighbours, and Ruth and Paul incessantly playing ‘the banana song.’ Yes, We Have No Bananas was a popular foxtrot of the early twenties, a song which Sam and Martha apparently considered beneath contempt. Eventually it was played only in their absence. Ruth was an avid antiquer and wrote to Wilbur of her finds in anticipation of his coming to join her in London and their doing some antique hunting together.

The following year Sam was still working in the office of Ivey, Elliott and Ivey and took on his first big case, acting for Mr. Tomer, plaintiff, in a case of wrongful dismissal, against Crowle, defendant. Although the suit dragged on for several years through appeals, the plaintiff was finally awarded in excess of $5,000.00 dollars, a very large settlement for 1929.

Sam’s credibility as a lawyer specializing in insurance received recognition in Toronto, when in 1922, he acted as solicitor for the Paramount Insurance Co. Founded some twenty years prior with a head office in Toronto, the company was now in the process of obtaining letters of patent. Sam’s application was successful under the provisions of the Ontario Insurance Act. He was not listed as one of the five directors, but he was considered to be a brilliant and promising young man at twenty-four years of age. Sam turned his expertise in real estate to mortgage his father’s property, taking out two mortgages in his own name for $2500.00 and $600.00. At that time, a large furnace, ‘Good Cheer,’ was installed at 139 Oxford Street West to the comfort and peace of mind of the entire family. No more constantly piling wood onto fireplaces to keep some warmth in their bones, nor waking up in a freezing cold house. The furnace was well named.

Perhaps it was Ben Baldwin’s business concerning the service station that brought Sam to Boston in 1923, ostensibly as a tourist, but also with an introduction to Horace Morison, counsel-at-law at 92 State Street. Morison took Sam and a ‘distinguished surgeon’ to dinner at the Harvard Club. Sam wrote to Morison some thirty years later, recalling that he had been very impressed and remembered the occasion with great pleasure. It would seem that Sam still had his eye on an international practice.

In 1923, he left Ivey, Elliott and Ivey, now Ivey, Elliott, Weir and Gillanders, and returned briefly to Meredith and Meredith, the largest litigation firm in Western Ontario. But it was a shortlived association, for in 1924, Meredith and Meredith dissolved their practice and Jeffery, Weir, McElheran and Moorhouse was established.

It was probably in the same year that, while on a business trip to Toronto, Sam saw Lothian Hills by Homer Watson (1855-1936) and fell headlong in love with it. Painted in 1892, prior to Watson’s excursion into an Impressionist style, the painting remains an example of Watson’s best period and was quite probably the single work of art which consistently over the rest of his life gave Sam the greatest pleasure and satisfaction. “It was,” he wrote to a friend, “my first purchase other than the wash drawing of Laura Knight’s.” He bought it on the instalment plan for fifty dollars a month directly from the artist. Lothian Hills was sold to Sam for $1000.00 less the commission of 33 1/3%. It was his in 14 months. Sam, Homer Watson and the artist’s sister, Phoebe, remained friends till the end of the lives of both Watsons. The painting continues to hold the place of honour over the fireplace in the main gallery of River Brink. Sam did not count the J.W.L. Forster portrait of Sir Wilfred Laurier, the oilette on canvas, “acquired for 50^ in my student days” probably in 1913 or 1914 as a serious part of his art collection or perhaps he had forgotten all about it.

In 1924 Sam and Martha were guests of a friend at Yale. Martha caught sight of a stone angel on the campus and never forgot her. A casting of the angel eventually found its way to the Frick Museum. Sam, Ruth and Martha each paid homage to it, Ruth in her capacity of her interest in an art gallery on Fifth Avenue and Sam on his frequent visits to New York. After Martha’s death in 1959 Sam started long and involved negotiations to bring a casting of the Ange de Lude to River Brink to overlook his home and garden in Queenston, Ontario. He wanted the statue as a memorial to Martha for whom he had planned an apartment for her use in his dream home.

“Yesterday was Ted’s birthday, but we all forgot it,” Ruth wrote to Wilbur in August of 1924, a sad commentary on her family’s attitude. That summer Sam was an acting prosecuting attorney and according to Ruth, “spends his days running around to small towns, doing his office work at night.” The chief bread winner of the family worked long hours and seems to have been taken for granted by the family. Ruth wrote to Wilbur of Sam’s knowledge of an expired chattel mortgage, listing some interesting things supposedly from the estate of Governor Higgins of New York State, and other items she thought would entice Wilbur to come up to London. Wilbur’s knowledge of antique furniture and of art objects in general, as well as of paintings, was a source of inspiration to both Sam and Ruth.

According to Ruth, one of the first if not the first, of Sam’s many vacations from his law office was to have taken place in the fall of 1924. Sam and Arthur Nutter, the architect and a frequent guest in the Weir home, perhaps a paying boarder, planned to drive to the West Coast, an adventure indeed in the automobiles of the time. However Arthur Nutter lost a considerable sum of money in a Florida bank crash at West Palm Beach and the trip was off. This was the first intimation of a restlessness in Sam that would show itself in frequent trips and excursions. Despite the material rewards of his law practice and the dividends from his growing portfolio, Sam was always ready to get out of the office and see the world.

Four generations, in 1929, the year prior to Martha Amanda’s death. Martha Amanda seated, careworn Sarah standing, and Ruth with her daughter, Sarah Howell.

Religious differences seemed to haunt Sam in his choice of young ladies. One such was a French Canadian, a staunch Catholic and a designer and creator of women’s fashionable wear. Possibly Sarah’s dressmaking activities were the means of acquainting them. However, an alliance with a Catholic was not to be thought of in George’s opinion and the young canadienne was not about to renounce her faith. Sam also had a dear friend whose parents were Presbyterians. Feelings over church union were still raw in the twenties and her parents forbade the development of a serious attachment with a Methodist. They remained friends throughout their lives and she never married. She felt that Sam’s home life was such that the taking of any prospective bride to meet the parents would be an impossibility.

In 1920 or thereabouts, Sam had met a young lady from Guelph, Mary MacDonald, known to her friends as Topsy. They corresponded incessantly by letter and apparently chatted on long distance telephone at great length like a pair of teenagers. Topsy was a keen horsewoman, so Sam took riding lessons in London, rode every morning before going to the office and joined the London Hunt Club. He does not seem to have made any other use of his membership. After the romantic attachment cooled down, he and Topsy remained friends and his enthusiasm for horseback riding waned. The social life of the London Hunt Club could be most exclusive especially to a member who was not considered part of the inner social circle of the city.

Sarah was surprised at his keenness for riding, but pleased that he was enjoying the morning exercise, albeit tempered with a certain reserve according to her letters to Ruth. She had come to depend very heavily on Sam as the man of the house and the prospect of his leaving Oxford Street and establishing his own home was not one she could look upon with enthusiasm. Sam realized the responsibility of his position as the only child left, not only at home, but in the vicinity. It was a weight on Sam’s shoulders and a strong factor inhibiting him in his social life and his seeking a wife.

The situation was relieved somewhat in 1925 when Martha Amanda, Sarah’s mother died at the age of 87. George Sutton and his mother-in-law had never been compatible. The high spirited Martha Amanda and the tyrannical George Sutton were at odds with one another, so much so in fact, that George was vehemently opposed to her being buried in a Bawtenheimer plot, particularly the one at Cape Croker. The clergyman’s widow who had subsequently remarried not once, but twice, was not fit to be buried beside the Reverend Henry in his opinion. Mrs. G.A. Bayne was buried elsewhere. Apparently Sarah’s mother had lent Sarah some money. In a letter shortly before her death she advised her daughter that she would “take interest at 5 1/2% for the present. Don’t worry about the principal.” Earlier in the year Sarah had received a short note from her mother in which she discussed the weather and the state of her health. A post script was curt and to the point, “You forgot to send the cheque.”

Sarah’s health continued to deteriorate. Despite being overworked, overtired and generally run down with anxiety, she seems always to have mustered strength enough to extend hospitality to Ruth with her little family in the summertime, occasionally to Wilbur and frequently to Arthur Nutter. Sam later angrily upbraided the architect for availing himself so frequently of the Weir hospitality, but it may well have been that Nutter was a paying guest and therefore a small help to Sarah in her constant battles with balancing her budget.

That same summer Ruth was anxious for her mother to come and visit her in her new home in Sunnyside, Queen’s County. Ruth wrote to Sam urging him to encourage not only Sarah to come but Paul also. Their fares were paid for by Ruth. This turned out to be Paul’s opportunity to leave home for good. He became a merchant seaman, sailing out of New York. By October of 1925, Paul had sailed through the Panama Canal, sent a postcard to George Sutton from Los Angeles and sailed up the western seaboard to Seattle, where he looked up his Uncle Samuel, Sam’s namesake. Paul’s comments on a postcard to Sam reveal much about Paul. He and the distinguished educator did not find much to say to one another. “Saw Uncle Sam,” he wrote, “too prosy and long winded to suit me, but he’s distinguished looking and students like him.” Samuel’s opinion of Paul is not recorded.

The summer following Paul’s becoming a sailor, Martha, he and Ruth took a motoring holiday in Quebec. Paul, who now wanted to be called Carl, managed to get into an automobile accident near Three Rivers. Ruth was unhurt, but Carl was shaken and Sam was called upon to help his brother. Later Ruth would write to Sam that their brother had been drinking again as though it were not an unusual occurrence. Carl’s frequent headaches and pains had made him extremely irritable and hard to bear, but the family made allowances constantly and forgave him again and again. Apparently Carl got off lightly with only a fine. In a letter to Wilbur, Ruth had made mention that she missed her nightly cocktail while in London in the Weir’s teetotal regimen. However, by this time, Martha could be enticed to take a little alcoholic refreshment. Times were indeed changing with the young Weirs at least.

At Ruth’s suggestion, Sam wrote to the Romanian Charles Wilfred Paul, born 1900, pictured circa 1925 in New York City ambassador in Washington offering his services as honorary consul for Ontario, together with letters of recommendation from Ruth and from an influential friend of Ruth’s, a Madame Sihleanui. Although it was arranged that Sam should meet the ambassador in Detroit, nothing came of it. Sam was ever on the alert to enrich his spheres of influence. It would appear that the handling of relatively minor legal matters was becoming increasingly boring and restricting to a brilliant and restless mind filled with curiosity, eager to know and understand in depth whatever was encountered.

Charles Wilfred Paul, orn 1900, pictured circa 1925 in New York City.

In June of 1926, a damaging story concerning Sam made the front page of the London Free Press. “HOLD-UP IS CHARGED IN HOTEL SITE” trumpeted the paper. Sam had acted as Trustee in an Indenture of Mortgage dated October 1920 and duly registered in London, made to him by the Benson Hines Company Limited securing the sum of $50,000 with interest, trustee’s compensation and costs against the lands. The committee for the Lloyd George Hotel Site on Richmond Street refused to pay what in Sam’s opinion and what in fact was the cost of administration of the mortgage over six years. The Free Press thundered in bold face type, “Demand for what is alleged ‘handout’ bar to million dollar proposition…Hotel committee refuses to make ‘donation’ on grounds of moral right.”

Sam sued the London Free Press for $10,000 libel claiming damages and costs. By September of 1927, the case was settled with an apology to Sam in the Free Press and $50.00 for Sam’s costs. Sam claimed that the story libelled him and damaged his reputation. He had retained John McEvoy of Toronto to represent him, showing his distrust of the legal fraternity in London. Sam was sure that somehow there had been a misrepresentation tipoff by person or persons unknown. He wrote to the editor demanding to know the source of the story, but was unsuccessful. His notation at the bottom of the docket with its angry initials, so angry that the pen almost sliced through the paper, gives evidence that Sam felt there had been backbiting envy and a vicious attempt to discredit him. That there was some justification for Sam’s thinking can be appreciated when it is remembered that to many of his contemporaries he was still ‘Little Monkey,’ the boy who had come to school in tattered clothing, the upstart young lawyer without a bachelor’s degree who was making a habit of winning his cases. It had been someone’s delight to spread the rumours that Sam’s father had been the town dog catcher and that his mother was half red Indian, both of course untrue and viciously meant to discredit him in the environment of a small Ontario town’s attitude in the twenties and thirties.

Sam and John McEvoy, later the distinguished judge, had come to know each other the year before when they both acted for a Mr. Brownlee, plaintiff, in a suit brought against a Mr. Zinn. Zinn’s automobile had collided with Brownlee’s horse drawn waggon and Brownlee subsequently died of his injuries. The fate of the horse is not recorded.

While on one of his many business travels, Son of the Pioneers, a painting by Marc Aurele de Foy Suzor-Cote (1869-1937) caught Sam’s eye and he bought it forthwith. He immediately wrote to Suzor-Cote and the letter was answered by Suzor-Cote’s brother who handled his brother’s affairs while the artist was living in France. A close relationship developed over the years, first with the brother, then with Suzor-Cote’s widow. Sam, by now a collector in the truest sense of the word, conceived the idea of acquiring an example of each one of Suzor-Coté’s bronzes, a project in which he almost succeeded. Naturally a relationship with Roman Bronze Casting of New York developed on very cordial terms. Roman Bronze had a contract with the Suzor-Cote family to make all of the artist’s castings.

Sam’s clients often complained of overly lengthy waits to get their work done. His somewhat jaunty replies were usually to the effect that he had been or was about to go on holiday. Sometimes he blamed illnesses and chest problems, and it is true that pneumonia and flu attacks did bother him frequently. However, procrastination was a habit which would aggravate clients and sully his reputation as a brilliant advocate, although his meticulous thoroughness in preparation and attention to detail would win the day in the end. As well as making himself an expert of outstanding ability in the legal side of obtaining mortgages, Sam’s natural bent for doing everything with the uttermost thoroughness led him into the adjacent field of the legal aspects of home building. By 1927, he had built the last house on the property acquired from his father, at profit to himself. London had grown and there were no more cows in the back garden.

Sam was also instrumental in forming Canadian Mortgage Investment Trust with Wilbur F. Howell as President, three other directors and himself as Secretary-Treasurer. Even though his reputation as an able counsel in mortgage and insurance matters and as a winner in various court cases was growing, there was no acceptance of him in London society. Because of insensitive treatment he had received earlier, social acceptance assumed an importance for him that was to become an obsession and a source of great bitterness. He had bested some of London’s legal scions in court and that would never do. Becoming wealthy and thumbing his nose at the town’s social set was his answer to the snubs.

Always with a keen sense of where to invest, Sam formed London Home Builders, the first housing development in the city and became its secretary in the boom days of early 1929. Wilbur was also on the board and the head office was located in New York City, presumably with the intention of attracting American capital. From 1929 until 1940, Sam caused his name to be put on every law list he thought germane to his area of expertise, British, Irish and American.

Early in his career he had been invited to join a law firm in Baltimore as a partner, but declined with regret. He could not take his parents along and he felt he could not leave them alone. His practice was going well in 1930, even with the onslaught of the Depression and he very prudently invested whatever he could spare in United States securities, although there was always something left over for his growing art collection. Many of his mortgages were foreclosed in the dark days of early 1930, but nevertheless Sam always seemed to come out on top.

As has been noted, even from childhood Sam had a deep love for beautiful flowers and shrubbery. Characteristically he read widely and informed himself in the study of horticulture and botany. It was to be typical of Sam’s way of getting exactly what he wanted that, when he decided to have a showy bed of iris in the garden, he contacted the two best known firms in Paris, France, the world leaders of the iris trade, and ordered a total of seventy five rhizomes, specifying in great detail the specimens that he wished. It was in the last year of prosperity, 1928, prior to the stock market crash, that Sam began to order flower stocks in profusion.

Two significant works of art were added to the collection in 1930. Laurentian Landscape by Franz Johnston was bought by Sam at an auction at Waddington’s in Toronto for $21.00 and Canada West was acquired from a London dealer, who subsequently was asked to look out for legal portraits, an embellishment Sam probably had in mind for his office.