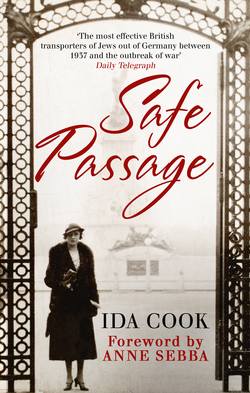

Читать книгу Safe Passage - Mary Cook - Страница 4

FOREWORD

ОглавлениеRomance is not just about love. It’s about an attitude to life, and there is little more romantic than a profound faith in the possibility of all things. It could be a belief that when you kiss the ugly toad he will turn into a handsome prince, just as much as a conviction that if you do the right thing you can, against all the odds, save a life. What could be more romantic than helping people, strangers, otherwise condemned to likely death, escape their own country and survive in a new one? For Ida and Louise Cook the spirit of hope, the conviction that everything would come all right in the end, was the essence of life. It pervades the romantic novels written by Ida, but it also guided the daily existence of both sisters. No matter what evils they encountered in the world, what remained constant for them was hope.

Thirty years after the death of romantic novelist Ida Cook such faith seems more necessary than ever. Their story has particular resonance today, at a time when Europe is facing the biggest refugee crisis since World War Two and many countries are being asked to provide shelter for hundreds of thousands of homeless people fleeing despotic regimes and torture. Britain has a reputation for tolerance, of being a country which has absorbed small movements of people in the past such as the Huguenots—French Protestants who came in their thousands—in the late 17th century. But in the years leading up to World War Two, although there was some sympathy for the plight of Jews trying to escape Nazi brutality in Austria, Germany and Czechoslovakia, there was also considerable hostility and above all, fear. Far from opening its doors to all those in need, the Government introduced tightly controlled entry visas designed to keep out more people than it let in. Today, the numbers seeking entry to Britain and other European countries from the Middle East and Africa are incomparably greater, but the arguments against allowing refugees or asylum seekers into the country are depressingly familiar: are they genuinely in need of asylum or are they economic migrants? If we welcome them will they “fit in” to our culture, or will they take our jobs? Fear of the other often remains a stronger emotion than sympathy.

Ida and Louise were not concerned with numbers or demographics. Fear they banished from their minds. When I first discovered We Followed Our Stars it was the unshakeable faith of Ida and Louise Cook that they could make a difference which hooked me immediately. It was the artless innocence of two young women flying to another country—at a time when flying itself was dangerously new—and defying that country’s laws to help desperate people they did not know, that made such a profound impression. I was moved by the sisters’ certainty, so rare today in a world where moral equivalence holds sway, that they knew without any ambiguity a clear difference between right and wrong. Since then, in the course of my own research into this period, I have come to recognise a hunger to share stories that many who lived through those years may have nurtured silently for almost a lifetime; yet they recognise that now this is their final chance before the generation that lived through the last War has died out, to share those emotions and experiences.

Ida and Louise Cook were born in Sunderland, northeast England, at the beginning of the last century; Louise, quieter and more intellectual, in 1901; Ida, naturally garrulous, three years later in 1904. Both came to maturity during the harrowing years of World War One, a war which wiped out almost an entire generation of young men in England. They were two ordinary women who lived in extraordinary times, spinsters who knew there would not be enough men available as husbands and who were unfazed by that; determined to live meaningful lives, lives that were more fulfilled than those of many other women at the time.

In the pages that follow there are innumerable examples of their pluck, to use an almost forgotten contemporary word. How Louise would leave her drab civil service office on a Friday evening, dash to Croydon Airport for the last plane to Cologne, then the night train to Munich, where they would, with luck (Ida often credits things going right to good luck, too modest to recognise it was good planning instead), arrive for breakfast on Saturday morning. Minor inconveniences such as toothache and overdrafts were ignored. They spent so much of their own money on these rescue missions that Ida admits towards the end of the book she was £8,000 in debt (equivalent to over £300,000 today).

Money was never one of their gods. They designed and sewed their own clothes, travelled third class and, even when Ida, known as Mary Burchell, became one of Mills & Boon’s best-selling authors earning almost £1,000 a year from her novels, they still usually sat in the gallery rather than the stalls of their beloved Covent Garden. “We spent thousands in our imagination,” she wrote when her advance for two books was a mere thirty pounds. By the time she was earning thousands, she had other ideas.

The problem they were confronting was that the British Government, since the Nazi seizure of power in 1933 when Jews had been gradually stripped of all rights, had allowed very few Jewish refugees to flee to Britain, and then only if financial guarantees for their future stability were in place. The situation deteriorated dramatically in November 1938 following the outburst of violence at Kristallnacht, when thousands of Jewish homes and businesses in Germany were destroyed and looted. This night of carnage shocked many British people who until then had ignored the plight of the Jews in Germany and Austria. The British Government now agreed to ease immigration restrictions for Jewish children but were still not prepared to allow unlimited entry for adults, many of whom found it impossible to leave. In this crisis private citizens or organisations had to come up with guarantees to pay for each child’s care and education or, for an adult, to provide assurances that they had means of support and would not be a burden on the public purse. For a woman, this usually meant entering domestic service. Adult men, accepted in Britain only if they had documentary proof that they were in transit, therefore faced the direst problems. Thousands, unable to leave their homeland, were later murdered. Such a domestic policy is not one to be proud of and some of those urging a more active response to today’s global refugee crisis are acutely aware of where we failed seventy years ago.

Ida and Louise, partly in order to make financial guarantees easier and partly because they recognised that those they were rescuing hated the idea of living off charity, offered to smuggle out valuables—mostly jewellery and furs for sale so that the refugees could have something to live on once they arrived in England. But in late 1930s Nazi Germany, smuggling currency or valuables was a serious crime. By helping opponents of the regime, as they did on at least one occasion, they risked their own lives. Yet the only precaution they took was to vary their return journey—perhaps coming home through Holland, catching the night boat and arriving at Harwich early on Monday morning so that Louise could walk into her office just in time. Their only weapon: faith in their dark blue British passports.

Ida describes their journeys (how many of them she doesn’t say) straightforwardly, not enhancing her or her sister’s role with the narrative storyteller’s skills at her disposal. There is no need for added drama. It soon became, she says, a regular and serious pattern of work. Yet who can forget the image of the nervous and eccentric opera-loving sisters, an image they themselves encouraged as a ‘cover story’, wearing cheap and cheerful clothes, embellished with fine pearls, expensive wrist watches and other jewels? Once, Ida’s jumper was adorned with a particularly huge oblong of blazing diamonds— “someone’s entire capital”—which she had to pass off as “fake paste from Woolworth’s” until she was safely back in England.

The smuggling was, she says, “a simple procedure.” But Nazi guards often boarded the train at the frontier for currency inspections. “This made things a bit awkward,” she writes blithely of an experience that for most young women (or men) would be heart-stoppingly fearful. “We both had rather ingenuous faces!” she says by way of explanation. And yet she admits that they started to be known at Cologne airport “and some awkward and unfriendly questions were asked.”

Soon they were doing more—organising forged documents, travelling the country giving talks as a means of raising money and awareness, and even buying a small London flat for the refugees to live in while they, women in their thirties, continued to live at home with their parents in South London.

But if fear was a forbidden emotion, sympathy and pain certainly were not. Neither sister was ashamed to shed tears, mostly at the agonising knowledge of the many they could not save and the likely suicides that would result. There was one occasion when a “case”, as the refugees were called by them, was imprisoned in a small country town in Germany. Ida used the same ingenious creative imagination which made her such a compulsively readable author by inventing a complicated plot to save the man’s life. She typed out a fake official letter stating that a very important man in the City of London was giving the financial guarantee and arranging to have a question asked in the House of Commons. She had a solicitor witness her signature and put a seal on it and, just as she hoped, the man was released and eventually escaped via Switzerland.

In order to demonstrate their lack of fear they chose deliberately to stay in the big luxury hotels, the Adlon or the Vier Jahreszeiten, where the Nazi chiefs stayed, wearing the borrowed furs with English labels freshly sewn in that they were taking back to England. “Then, if you stood and gazed at them admiringly as they went through the lobby, no one thought you were anything but another couple of admiring fools. That was why we knew them all by sight, Louise and I… Goering, Goebbels, Himmler, Streicher, Ribbentrop. We even knew Hitler from the back.” Not only does Ida make light of their courage, self-deprecatingly she describes her behaviour as “ignorant.”

“We didn’t know—imagine!—in those days we didn’t know that to be Jewish and to come from Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany…had the seeds of tragedy in it.” This was when their first case, Frau Mitia Meyer-Lissman, the official Salzburg lecturer, was entrusted to their care. Thanks to her they soon “saw things more clearly and understood the full horror of what was happening in Germany.” Mitia Meyer-Lissman escaped to live in England and after the War her daughter, Elsa, a seventeenyear- old music student when she first met the Cook sisters, became a renowned lecturer at Glyndebourne, the country house in Sussex where opera was performed and which became a haven for several German musicians forced to flee.

The sisters were in Salzburg for the annual music Festival in 1934, the year Engelbert Dollfuss, the Austrian pro-fascist Chancellor, was assassinated in a bungled Nazi coup attempt. “I blush now to think how ignorant we were of the significance of this event…we were concerned with only one aspect of the murder: would it put a stop to our holiday?” Ida wrote in 1950. But in fact no music lover that summer could have avoided the sense of menace, the atmosphere of doomed enchantment that hung over the Festival. And right in the centre of this maelstrom was the charismatic and controversial Austrian conductor, Clemens Krauss.

Krauss is the enormous and looming shadow that stalks the book. Krauss, an elegant, sometimes dictatorial conductor, was, by virtue of his friendship with Richard Strauss, a direct link to the source of musical creation. Director of the Vienna State Opera and later the Berlin State Opera, Krauss was ambitious to revive the musical life of Salzburg and he set audiences alight with fervour. He and his glamorous wife, the Romanian soprano Viorica Ursuleac, had what today would be called A-list celebrity status, and Ida and Louise were, unquestionably, star-struck.

It was only because of Clemens Krauss and his wife that Ida and Louise started their rescue work and they could, or would, never have maintained it without the constant encouragement and help of those two. His offer to stage favourite operas chosen by them gave added authenticity to their story if questioned by Nazi guards on their travels. But it also took them right to the heart of their earthly pleasures and dreams. Ida is honest enough to recognise that, although it was the pursuit of opera which initially brought them to the refugee work, it was now the pursuit of the refugee work which was made possible only by the support of the great operatic performances. She insists that it was the same naïve technique by which they first learnt to save up enough money to visit the United States and meet famous opera singers in the twenties that helped them now as they “stumbled” into Europe and began to save lives. “You never know what you can do until you refuse to take no for an answer.”

But naïve, with its connotations of foolish ignorance, is not a word that fits Ida or Louise. Ida was too intelligent not to realise, when she came to write up her account of those years in her autobiography, that Krauss, who had had to defend himself to a de-Nazification tribunal after the War, was tainted by default. He had taken over preparations for the premieres of Richard Strauss’s opera Arabella after the dismissal of the non- Jewish but anti-Nazi conductor, Fritz Busch. Busch became the music director of Glyndebourne Festival Opera. Ida writes of Krauss: “I knew that to speak in praise of any artist who occupied a high position in Hitler’s Germany is to tread on very delicate ground. At the first word, even now, tempers rise, private and professional axes are taken out and reground, and friend- ships tremble in the balance. But, in that homeliest of phrases, one must speak as one finds.”

Hindsight is easily acquired and if Ida and Louise had been ignorant in 1934, they were unusually far-sighted two or three years later. In the appeasement debate which raged around Britain in the thirties, many of those who thought that the only way to prevent Hitler was to fight him, were accused, like Winston Churchill, of warmongering. Others, such as Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, believed Hitler was a man who could offer Britons ‘Peace with Honour’.

A number of so-called intellectuals in Britain in the 1930s— not just those who were openly anti-Semitic or pro-Hitler such as Unity Mitford, but those who worshipped German art and culture—refused to believe ill of Hitler or a country which had produced Beethoven, Goethe and Wagner. The popular historian Arthur Bryant, for example, could write in 1937 of German fascists as “peaceable and ordinary folk” fighting for decency, tradition and civilisation and, even after Kristallnacht, said of Jews that they had “seldom been welcome guests and scarcely ever for long.” He argued that they should not be welcome in Britain because they were likely to acquire “an unfair and disproportionate amount of wealth and power,” arguments not so different from debates raging in Britain in the early 21st century based largely on fear of what the new immigrants might take.

Yet Ida and Louise, scarcely educated as they had been, were not fooled. They were able to distinguish between high art and fine music and bestiality. They understood that Anglo-German friendship did not require conniving with Hitler to kill Jews. They were born with an innate moral gauge, a spirit level in the brain that tilted as soon as they smelled evil. Courage they learned along the way.

The two characters in the wings of this book, not entirely offstage, are the Cook parents: James, who worked in Customs and Excise, and his wife, Mary; the book’s dedicatees. As well as the girls, there were two sons, Jim and Bill. “Both parents set a standard of personal integrity that gave us children a neverquestioned scale of values and made life so much easier later on,” explained Ida.

One of the most appealing scenes of domestic tranquillity in the book has Ida describing to her mother how they had returned from a particularly harrowing time. “I went straight through into the kitchen where mother was making pastry—which is after all one of the basic things of life… If she had stopped and made a sentimental fuss of me I would have cried for hours. She just simply went on making pastry…she told me ‘you’re doing the best you can. Now tell me all about it.’” The period of which Ida is writing is not so long ago and yet, to read of the way she extols family values seems like another world, another era. At the same time there is a timeless quality to the sisters’ response to desperate people. Their insistence on trying to save whole families is just one aspect of what made their work so unusual; elderly aunts, uncles as well as parents were included too, if possible, just as today images of young children and babies clinging to parents desperate for warmth, food and a roof over their heads flood the media.

And through it all is the music; glorious arias permeate the pages. Music shored up their belief “that there was another world to which we would be able to return one day. Beyond the fog of horror and misery there were lovely bright things that they had once taken for granted.” The world of music is, after all, deeply romantic. Of all the arts it is arguably music which has the greatest transformative power; within musical genres, it is opera where rational belief has so often to be suspended.

Ida recognised the absurdity of sublime music existing in the midst of a hell hole. But she saw it rather differently. She saw the music as something that counterbalanced their unhappiness at the cruelty they were forced to witness. She refers at one point to the power they had to decide the fate of an individual, power she loathed because of the “terrible, moving and overwhelming thought—I could save life with it.” But the real power in the book is the redemptive nature of music and especially the high drama of operatic music. These two spinster sisters knew that, in the presence of their Prima Donna heroines, or Angels as they appeared to Ida, they could pull on their home-made cloaks and assume different personae themselves.

Now that’s romance.

After the War Ida and Louise settled back in to the family home in South London where they had lived for the last sixty years and into the safe and familiar routines of work and opera. But, in 1950, after Ida published her autobiography, We Followed Our Stars, the pair were soon bathed in a halo of publicity and embarked on a round of parties and award presentations. Several of the refugees campaigned to have Ida and Louise’s work recognised by Yad Vashem, the Israeli authority which honours those who helped save lives during the Nazi period. In 1965 the sisters were declared “Righteous among the Nations” in recognition of their work in rescuing Jews from Germany and from Austria during the dark days of the Nazi regime and in helping them to rebuild their lives in freedom. The citation mentioned “twenty-nine families” but the total number of those they helped must be triple this, not all of whom were Jewish.

They never went to Israel, receiving the certificate instead from the Israeli Ambassador in London. In 1965, they were two among only four Britons to be so honoured and few people other than those directly involved knew their story. But in 2010 the British Government announced a new award, British Heroes of the Holocaust, to recognise those from this country who had risked their lives to help others escape. Ida and Louise Cook were among twenty-five individuals, including Sir Nicholas Winton, the Briton who organised the rescue of 669 Czech children, and Frank Foley, who worked for the Foreign Office in Berlin and helped thousands of Jews escape by bending the rules on passports, most of whom were posthumously declared British Heroes of the Holocaust.

Ida, the talkative sister, was the one to whom journalists had always addressed questions and whose fame as a novelist attracted attention. But she was always insistent that whatever honour was granted, it must be for both of them. As she never tired of pointing out, it was Louise who embarked on learning German in order to conduct the interviews. But there was something much deeper. They were dependent on each other. Briefly feted though they had been, especially in America, which had become home for some of those they rescued, their lives remained essentially unvaried until the end. Ida continued to write romantic fiction for Mills & Boon and one work of non-fiction, a ghosted autobiography of the singer Tito Gobbi, her close friend, in 1979. But her heroines belonged to an earlier world. Her publisher, Alan Boon, commented: “Mary Burchell wasn’t sexy but she showed an awareness of it…it was a pretended form of sex, not suggestive in any way at all. It was instinct, not participating.”

Neither sister married but that does not mean they did not have romantic lives. They lived vicariously through their music, through their work and through their refugees. Ida was never ashamed of believing in romance or of writing romantic novels. When she took over as President of the Romantic Novelists’ Association in 1966 she declared: “Romance is the quality which gives an air of probability to our dearest wishes… People often say life isn’t like that but life is often exactly like that. Illusions and dreams often do come true.”

Ida died at home on December 24, 1986 aged 82. Louise outlived her by another five lonely years. Obituaries talked of the sisters’ “Scarlet Pimpernel” operation. One of those refugees who wrote to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem in support of their cause described them as “Human Pillars”. Ida said simply: “We called ourselves Christian and we tried to do our best.”

Anne Sebba, London 2008-03-20

Updated London 2015-12-19