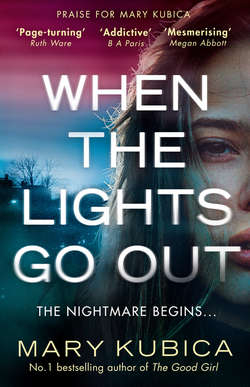

Читать книгу When The Lights Go Out: The addictive new thriller from the bestselling author of The Good Girl - Mary Kubica, Mary Kubica - Страница 19

Оглавлениеjessie

I push my way through the turnstile doors and step outside, making my way across the plaza. Beside the Eternal Flame, I pause, overcome with the sudden urge to scale the fence and lie down beside the puny little fire in the fetal position. To fall to my side on the cold concrete, beside the memorial for fallen soldiers. To pull my knees up to my chest in the middle of all those pigeons who huddle around it, trying to keep warm. The land around the flame is thick with birds, the concrete white from their waste. That’s where I want to lie. Because I’m so tired I can no longer stand upright.

People breeze past me. No one bothers to look. A passing shoulder slams into mine. The man never apologizes and I wonder, Can he see me? Am I here?

I head to the bike rack, finding Old Faithful ensnared beneath the pedals and handlebars of a dozen or more poorly placed bikes. I have to tug with all my might to get her out and still I can’t do it. The frustration over my identity boils inside me until I feel myself begin to lose it. All this red tape preventing me from getting what I need, from proving who I am. I’m starting to question it myself. Am I still me?

The debilitating effects of insomnia return to me then, suddenly and without warning. General aches and pains plague every muscle in my body because I can’t sleep. Because I haven’t been sleeping. My feet hurt. My legs threaten to give. I shift my weight from one leg to the next, needing to sit. It’s all I can think about for the next few seconds.

Sitting down.

Pins and needles stab my legs. I wrench on the bike, yanking as hard as I can, but still she doesn’t budge. “Need a hand?” I hear, and though clearly I need a hand, there’s a part of me feeling so suddenly indignant that I turn with every intent of telling the person that I’ve got it. Words clipped. Expression flat.

But when I turn, I see a pair of blue eyes staring back at me. Royal blue eyes like the big round gum balls that drop down the chute of a gum-ball machine. And my words get lost inside my throat somewhere as I rub at my bleary eyes to be sure I’m seeing what I think I’m seeing. Because I know these eyes. Because I’ve seen these eyes before.

“It’s you,” I say, the surprise in my voice clear-cut.

“It’s me,” he says. And then he reaches over and hoists Old Faithful inches above the other bikes, those that have held her prisoner all this time. It’s effortless to him, like nothing.

He looks different than the last time I saw him. Because the last time I saw him he was folded over the cafeteria table, drinking coffee in a sweatshirt and jeans. Now he’s dressed to the nines in black slacks, a dress shirt and tie, and I know what it means. It means that his brother has died. His brother, who was hurt in a motorcycle accident after a car cut him off and he went flying off the bike, soaring headfirst through the air and into a utility pole without a helmet to protect his head.

He held vigil beside his brother’s hospital bed while I held vigil beside Mom’s. And now, six days later, his eyes still look tired and sad. When he smiles, it’s strained and unconvincing. He’s gotten a haircut. The dark, messy hair has been given a trim and though it’s not prim or tidy—not by a long shot—it looks clean. Combed back. Much different than the hair I saw those days and nights in the hospital cafeteria, his head stuffed under the hood of a red sweatshirt. We only spoke the one night, him fussing about the coffee, telling me how he’d rather be anywhere but there. But still, there’s the innate sense that I know him. That we shared something intimate. Something much more personal than coffee. That we’re bound by a similar sense of loss, united by grief. Both collateral damage in his brother’s and my mother’s demise.

He sets Old Faithful down on the ground and passes the handlebar to me. I take her in my hand, seeing the way his nails are bitten to the quick, the skin torn along the edges. A row of rubber bands rests on his wrist, the last one tucked halfway beneath the cuff of the dress shirt. A single word is written on the back of the hand with blue ink. I can’t read what it is.

He runs his hands through his hair and only then do I think what I must look like.

It can’t be good.

“What are you doing here?” I ask, as if I have any more right being here than him.

He speaks in incomplete sentences, and still I get the gist. “The wake,” he says. “St. Peter’s. I needed some air.”

He points in the direction of some church just a couple of blocks from here, one that’s too far to see from where we stand. Though still I look, seeing that the sun has slipped from the sky and is hidden now behind a cloud. While I was inside the building, the clouds rolled into the city, one by one. They changed the morning’s blue sky to one that is plush and white, filling the sky like cotton balls, making the day ambiguous and gray.

I don’t ask when or how his brother died and he doesn’t ask about Mom. He doesn’t need to because he knows. He can see it in my eyes that she has died. Neither of us offer our condolences.

He rams his hands into the pockets of his slacks. “You never told me your name,” he says. If I was the kind of girl that felt comfortable in situations like these, I’d say something snarky like Well, you never asked.

But I don’t because it’s not that type of conversation, and I’m not that girl.

“Jessie,” I say, sticking my hand out by means of introduction. His handshake is firm, his hand warm as he presses it to mine.

“Liam,” he says, eyes straying, and I take it as my cue to leave. Because there isn’t anything more to say. The one and only conversation we had in the hospital, words were sparse, but unlike in the hospital we’re no longer killing time, just waiting for people to die. That night, before the conversation drifted to quiet and we sat in silence for over an hour, sipping our coffees, we talked about private things, nonpublic things, things we weren’t apt to tell the rest of the world. He told me about his brother beating him up when they were kids. About how he would lock him out of the house in the rain and shove his head in the toilet, giving him a swirly when their folks weren’t home. Such a bastard, he said, though I got the sense that that was then and this was now. That over the years, things changed. But he didn’t say when or how.

I told him about Mom’s hair and fingernails, both of which she lost thanks to chemotherapy. Her eyelashes too. I told him about the clumps of hair that fell out, and how I watched on in horror as Mom held fistfuls of it in her hands. How there were whole clods of it on her pillowcase when she awoke in the morning, masses of it filling the shower drain. I said that Mom never cried, that only I cried. It grew back, after the cancer was in remission for the first time, soft fuzz that grew a little thicker than it was before chemotherapy. A little more brown. It never reached her shoulders before the cancer returned.

“You should get back to the wake,” I tell him now as we stand there in the middle of Daley Plaza. But he only shrugs his shoulders and tells me that the wake is through. That everyone split.