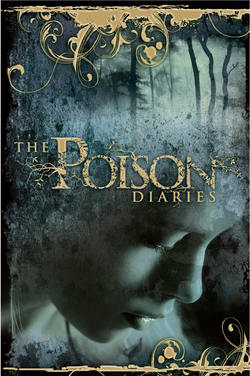

Читать книгу The Poison Diaries - Maryrose Wood - Страница 10

Chapter Five

Оглавление25th March

THE WEATHER HAS SHIFTED. THE BREEZE IS WARM AND full of promise. No time to write more. I have to tend to Weed.

Today is the first day of a new season.

It is the season of Weed.

He is not much company yet. All day and all night he hides in the coal bin, hunched and silent. Father says it must be because that is what he was accustomed to at the madhouse, but I think Father may have frightened him with his wild talk of throwing poison into wells; it is no wonder he does not wish to speak to us. So far he has refused to eat most of the food I bring, though he will drink as much water as he is offered.

I will be patient. Any wild creature can be tamed, if you are willing to wait and be still. I have learned this from the feral cats that lurk around the courtyard. They stare like yellow-eyed demons; they bolt and hide if you approach, but sooner or later, when they are hungry enough, they come and take the food from your hand.

So it will be with Weed – but not yet. In the meantime I have decided that I will introduce myself to him, to get him accustomed to my presence. He may not answer me at first, but that is no matter. I have someone to talk to, at last! My words will be like sunshine and air. My voice will rain down on him, and then we shall see what glorious orchid may blossom from this shy, unwanted Weed.

I race through my chores in half the usual time so that I may spend the rest of the day taming my new friend. Since he will not leave the coal bin, I carry my small stool down to the cellar and sit as close as I dare.

“My name is Jessamine Luxton,” I say, as a way to begin. “I am sixteen years of age. My father is Thomas Luxton, the apothecary. You have met him already; he was the one that picked you up off the ground and brought you inside the cottage, after that dreadful man on horseback left you lying in the dirt like rubbish.”

While I speak he stays facing away from me, his body curved around his knees as if he were encased in the hard husk of a seed.

“So,” I say, nudging my stool an inch closer, “now you have met Father and me. That means you have met my whole family, for my mother is dead, and I am an only child. My father and I live here on our own.”

I see a finger twitch, flex.

“This place we live in, this house, which I call our cottage – it is very old. Some would say it is a sacred place. The Catholic monks used to live and worship here.”

He turns, and his mouth moves as if he would speak.

“Bells,” he breathes.

His voice is so soft it is not even a whisper. More like the rustle of a leaf.

“Yes,” I say encouragingly, in case I heard right. “Centuries ago, in this very place, there were church bells ringing, and Mass bells, and the call to vespers. When the monastery was here there must have been bells ringing all the time.”

“Bells.”

I am nearly sure that is what he said, but it was so soft, a mere flutter of air. “Bells?” I repeat gently. “Do you mean Canterbury bells? They are such pretty flowers, I grow them in my cutting garden.”

Weed’s whole face brightens. “Garden?” he asks, quite clearly.

His green eyes pierce me like emerald daggers. “Do you like gardens? We have many,” I say in a rush. “In the kitchen gardens I grow all our vegetables and herbs for the table, and there is a small orchard for fruit, and a bee garden so the bees will make delicious honey, and a dye garden so I can make dyes to colour the wool. And Father has his apothecary garden of plants that he uses to make medicines and cures – but we may not enter there, for Father’s work is secret, and many of those plants are poison—”

“Jessamine!” Father stands silhouetted at the top of the cellar stairs. “What on earth are you telling that boy?”

“Nothing—”

“Do not lie, Jessamine. I heard you speaking. A person cannot speak nothing.”

“I am sorry, Father. I should have said, ‘Nothing of importance’,” I reply with false cheer, to cover the shame I feel at being scolded in front of Weed. “I was telling Weed about us, and our home, and about the gardens – he ought to know where he is, and in whose care, oughtn’t he?”

Father ignores my reply. “Since he is ready to speak, bring the boy upstairs to my study. At once please.” Then he leaves, letting the door close behind him. The shaft of daylight coming down the stairwell is snuffed out.