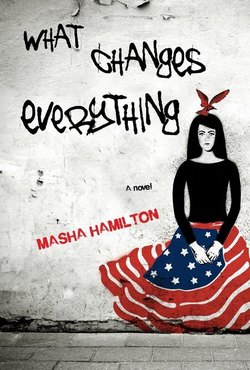

Читать книгу What Changes Everything - Masha Hamilton - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTodd

September 4th

The argument had tumbled forward for almost twenty minutes now and had already begun circling back; Todd was ready for ice cream. To a casual observer, the debate might seem one-sided; after all, Amin did all the talking. But Todd had a knack for disagreeing without speaking. His was the art of those too cautious or too isolated to engage in frank exchanges. He'd refined it over years of working far from home, challenging himself to seek persuasion through patience and through words used like pinches of pepper in a delicate dish.

"This isn't our work," Amin said. "I don't trust Zarlasht; her aim

is to manipulate," and then, with greater heat, "It's dangerous to in

volve yourself in a dispute of this sort, Mr. Todd— I feel a responsi

bility to make sure you understand this," and finally, "It's outside our

sphere of responsibility, anyway. We must concentrate on working

for refugees."

Todd smiled or grimaced now and then, nodded in a way that indicated nothing more than thoughtfulness, and occasionally glanced out the window. Though his vision was curtailed by the ten-foot-high whitewashed security wall that encased the compound, he knew that just beyond it lay the chaotic life of Kabul streets, where women in burqas clutched kohl-eyed babies and begged at stoplights and men pushing wheelbarrows loaded with bruised fruit swayed between cars with audacity, where underfed children scattered and regrouped to sell pieces of rusted metal intended for purposes Todd could never discern, where traffic lights and lane markings were thought to be for sissies and safe travel was achieved only through great boldness and luck. He longed for it. He longed especially now, stuck in a room of intellectual— and ultimately, he feared, irresolvable—discord.

Finally, blessedly, Amin paused for breath.

" Shall I get us some sheer yakh?" Todd asked.

"Why not simply have told her to return on Thursday instead of Wednesday?" Amin said, using what surely had to be the last of his arguing energy. "Then I could have said you were called out of town on an emergency. That might have discouraged her— or at least would have given me time to look into her claims, her family." Todd's travel plans were always secret; Amin, his closest Kabul colleague— no, friend— was the only person here who knew that early Thursday, just before fajr prayers, Todd would depart for Islamabad. By Thursday evening, he would be waist-deep in issues involving refugees in Pakistan, and Zarlasht would have been turned away at the gate. After four weeks in Pakistan, Todd would return for one more month in Kabul, his last. Then back to New York, and to Clarissa, for good, though Amin hadn't yet been told that, and of course that involved challenges of its own. Challenges not to be considered now; Todd always said his doctors insisted that, for his continued good health, he ignore all problems outside his current time zone.

"Because, Amin, we cannot simply dismiss this as beyond our mandate." Todd kept his voice neutral in contrast to Amin's heat. "You tell me the villagers are turning to the Taliban for justice. Well, Zarlasht is turning to us. If we do nothing, we are by default supporting the Taliban."

"How many years do I know you now, Mr. Todd? Long enough for me to say that you are still too trusting, and my words are not a— how do you say?—a compliment. You—"

But Todd held up his hand, cutting Amin off. "Wait, my friend. First . . ." He reached to a tray on a table in the corner, lifted two small glass bowls, and raised his eyebrows in a question.

Amin let out an exasperated breath. "Too late for ice cream," he said.

"Oh, Amin, we haven't reached the end of the world yet. And even then—"

"Your cook told me to strictly forbid you from eating ice cream after 3 p.m. because otherwise, you won't eat her dinners."

"Yes," Todd agreed. "Shogofa will not be happy with me. But there's nothing for it; sheer yakh it must be. It will clear our brains. Remember, we have the late meeting with the American nurse, Mandy Wilkens."

"I didn't forget," Amin said. "But Mr. Todd, do you really want ice cream, or just to escape my reasonable words?"

"The ice cream. Okay, mostly the ice cream." Todd, mock-somber, laid his palm on his chest. "I swear."

Amin shook his head in resignation. "One scoop," he said. "Only one."

Todd grinned as he headed out the office door and down the steps to the main entrance, where he slipped his shoes on. He nodded to his driver, Farzad, smoking by the car. "Salaam alekum," he said to Mustafa, the building guard, who emerged from a small room next to the metal gates. Todd raised the ice-cream cups as if they were admission tickets, which, in a way, they were.

Todd was required to travel everywhere by reinforced car with tinted windows: to refugee camps, government offices, the UN compound, the rare meal out, even the five blocks to the guesthouse where he slept. He sat in the back, with Farzad driving and Jawwid in the front passenger seat toting an AK-

47. Those who came to Todd's office were not allowed through the gate unless they'd made a prior appointment and even then were thoroughly checked by his guards. "Your safety is a matter of our honor," Amin had explained. Todd understood, but this meant that everything in his Kabul environment was tightly controlled, which was not the way he functioned best. To do his job well, he needed to walk down narrow, dusty roads as they descended into yet unknown villages and to visit the overfilled refugee camps. In fact, he came to life visiting homes fashioned of war rubble and roofed with UN-provided tarps, eating unimaginable food he hoped would not make him ill, witnessing the tremendous grace and imagination of the vulnerable. He loved the unexpected adventure of every day spent in the field. He got to do little enough of it as regional director, given all the desk work combined with safety concerns. And he'd soon be giving up even that.

But today he still had the ice-cream run.

Over the five and a half years that he'd been coming to this office, Todd had posited and reposited compromises to ease the restraints he faced in the name of security. At last his grumblings had evolved into a discussion: Todd, Amin, Farzad and Jawwid sitting on floor mats, drinking chai, Todd offering that both his job and his personal needs required more relaxed access to Kabul, at least occasionally, and the Afghan men talking among themselves at a speed that defied his limited Pashto. Finally, a little over a year ago, they had reluctantly agreed to let him walk the block and a half from the office to the ice-cream stand, no Jawwid at his side, no Farzad following in the car. But, equally firmly, nowhere else. So this had become his nearly daily outing, the only moments when he could imagine himself free in this teeming ancient city of conflict and joy and loss that enchanted him.

"How are you, Mr. Todd Barbery?" Mustafa asked in English as he opened the gate, making the second word sound elongated. Mustafa was the only Afghan who insisted on calling Todd by first and last name.

"Teh kha, manana," Todd responded, as was their practice. One in English, the other in Pashto, and sometimes they expanded their respective vocabularies in a fleeting language lesson. At the moment, though, Todd desired no further words. He kept moving, waved good-bye, and heard the gate clang shut behind him. The sound of freedom.

The air was golden, which really meant full of dust, but Todd chose to see it in more romantic terms. He walked slowly, lingering, stretching his leash to its ends. He admired the energy of this mountain-ringed city— founded, it was said, by Cain and Abel, visited by Genghis Khan, loved by Babur, beaten down over and over, but with a core of perseverance and unlikely optimism. He found the faces of its people beautiful, a human mosaic of endurance creased with dark but resilient humor. These were qualities he valued; Afghanistan had found its way into his blood. The ice-cream run was the most dependably enjoyable part of his Kabul day. He was grateful for the break from those who both helped him in uncountable ways and made him feel chained. And Afghan ice cream, seasoned with rosewater and cardamom and topped with grated pistachios, was a small miracle in a land that desperately needed miracles.

The boy Churagh ran to Todd, waving his newspapers. "How are you?" he said in over-enunciated English. Churagh had identified Todd as a soft touch; he bought a paper and gave the boy's arm a friendly squeeze. Sometimes they chatted and Todd bought a second newspaper. Today Churagh seemed to sense Todd's preoccupation; he followed but kept a distance. Though he wouldn't admit it to Amin, Todd was having trouble shaking the unease brought on by the conflict between his desire to help Zarlasht somehow and the strength of Amin's arguments. He wanted to play Zarlasht's visit over in his mind without Amin's voice in his ears.

This had been Zarlasht's third visit to Todd's office— too many for simple courtesy calls. Mostly, he was the one who called on government officials, and the visitors he did have at the Kabul office were usually NGO representatives, not hospital administrators like Zarlasht, so he'd been vaguely uneasy about what she might want from him. When she'd arrived, she had not been shown to the meeting room full of cushions; instead, she'd sat on a chair in front of his desk. Amin stood in the corner so that Zarlasht would not suffer any harm to her reputation by being alone with a Western man. She wore, as always, a headscarf, no burqa. He guessed she was about forty years old, although he'd found that the stress and want of their lives took a toll on Afghans, and he knew she could easily be a decade younger.

The first time she visited, Zarlasht chatted without making any specific request; she said she'd heard good things about him and wanted to meet, since she worked as an administrator in Maiwand Hospital and often dealt with refugees. The next time, she told a story about her grandfather, a story of captivity and separation, her grandfather taken away by the Soviets and she a child, so scared, hanging on to his robe, chanting, "Please don't go, don't go, Granddad."

"Not to worry, my dear," the grandfather had said, a soldier flanking him on each side.

" Where are you going?"

"Only out to buy you a television set," the grandfather said, a story so improbable only a child would believe it. "I'll come back with it soon."

"When?"

"An hour. Two at most. Before dark, surely."

So she released her hold on him. And did not see him again for two and a half years— infinity in the life of a child— until he appeared one afternoon in the home she shared with her mother and grandmother. Sitting at the table, her grandfather smiled and raised his hand in greeting. But she didn't recognize the frail stranger. "Who is this man? Why is he here? What does he want?" she asked her grandmother, and at that, his smile slid away and he began to weep. They'd pulled out his nails in prison, roots and all, so he had only the soft ends of his fingers, and he'd received electric-shock torture so many times it had left a hole in his tongue. He couldn't eat, couldn't bear food in his damaged mouth, so he was fed intravenously until his death, less than two years later.

Political discord in this land had always been marked by blood and pain. The stories were unending, shocking the first time, sad but predictable after that. Still, Todd had been moved not only by her story but by the simple way in which she told it, without melodrama or any apparent attention to its effect on him. On the way out the door, almost as an afterthought, Zarlasht had mentioned a cousin who was being beaten by her husband.

That cousin was the focus of her visit today.

"Things are worsening for her," Zarlasht said, starting in even before the cup of chai arrived. "She can stand that her husband beats her, but she cannot stand the beating of her only daughter. Last week he poured boiling oil on the girl's legs. They will be scarred. We are lucky it was not her face."

"I'm so sorry."

"My cousin is determined to stop him," she said.

"She is brave."

Zarlasht turned her head away as she nodded. "My cousin's father went to the elders," she said, gazing as if at someone no one else could see. "He asked that a jirga be held to hear her complaints against her husband. They agreed at first, but now her husband has gone to them and sought their support, and they are threatening to cancel the hearing and instead punish her for speaking against her husband."

"Can't her father help?"

"He is not as powerful as her husband," Zarlasht said. "It is whispered that

the jirga wants to stone her for defying her husband and encouraging other

women to do the same. Also as a show of strength, so the foreign occupiers—forgive me, but this is how they speak— can see that sharia holds sway less

than seventy kilometers from Kabul. It's not her own life that she considers.

She doesn't want her daughter left alone with a father who views her as an object. In this case, the girl will have no future at all."

Zarlasht did not cry during this small speech, but her eyes were tight with an anguish that seemed so personal Todd felt sure she was speaking of herself, not a cousin. His natural impulse was to reach to squeeze her hand, but he knew this would violate all kinds of cultural protocol. He looked out the window for a minute instead, and then turned back. "I'm so sorry about all this, Zarlasht. But why come to me?"

"Because I know your reputation," Zarlasht said. "I think if you summon Haji Mulak, and you mention the name of my . . . my cousin's husband, it might make a difference. Say you want to know about the case of Hamid, his wife and daughter."

Todd smiled. "I fear your confidence in my reach is unrealistic."

"I don't think so. They talk about how you go to see the refugee camps, and how more food and doctor visits follow." Zarlasht paused, then spoke in a slightly softer voice. "And I have nowhere else to go."

That sentence hung in the silent room for a moment, sucking out its air. Todd glanced briefly at Amin, whose eyes carried a clear warning. "Give me a few days," he told Zarlasht. "Let me see if I can help. Come back Wednesday."

"Tashakor," she said, putting her right hand to her chest. "Ma salaam."

She barely looked at Amin as she left, and no sooner had she walked from the building than Amin began to argue. "This is not your business, Mr. Todd. It is a local affair. To interfere in this matter is not only useless but perilous. She must know this. So I wonder why she comes to you."

Though Amin was a private man, Todd had heard something of his past, enough to reinforce his trust in Amin's political instincts. As a teenager, Amin had waited on Najibullah while the ousted president was held in the UN mission. With the Taliban takeover, he'd fled over the mountains to Pakistan, joining other refugees. Eventually he got a scholarship to be educated in the States, then returned to Afghanistan. He had a wife, three daughters, and a son who lived outside Kabul and whom he saw only at week's end, leaving his brother to look after them day-to-day. Amin believed the best future for Afghanistan lay in an alliance with America, but he also believed Americans were blind to Afghan cultural nuances, failing to understand how telling someone what they wanted to hear had become a survival skill and how quickly and violently apparently seamless alliances could be shattered.

Todd generally followed Amin's advice; in fact, he wasn't sure he'd ever before resisted this insistent an argument. But Amin was all logic and reason, lists of pros and cons, risks to be considered, unlikely gains to be weighed. Todd knew all that; he knew what was allowed here, what wasn't, and still, in these last of his remaining days on the job, he wondered about the advantages of simply speaking out, trying to do the right thing. He knew better than to express that aloud; Amin would invoke cultural differences and surely call him naive besides.

From a half-block away, Todd could see a longer-than-usual line at the ice-cream stand, jammed not with the children who generally gathered there— even Churagh had given up trailing him— but with men, maybe a dozen. Odd; he wondered about it for a moment. Outside the enclosed marketplace, crowds were rare. Fear of suicide bombers always rumbled in the subconscious, and beyond that, of course, a group of any size drew the unwelcome attention of passing troops, whether Afghan or foreign.

He quickly dismissed his worry as paranoia— this was ice cream he was talking about— and joined the back of the line. He raised a hand to the two men dressed in long white overshirts and loose pants who dished the ice cream into cups on a table topped with a bright red, plastic sheet. By this time, the vendors knew Todd by sight and generally greeted him with big smiles. Sometimes he ate his ice cream right there in front of the stand, chatting with simple words, pretending for a moment he belonged and could linger casually. Now, though, they were too busy to acknowledge Todd, if they even saw him.

He turned his attention to the bakery next door. In a room not much larger than a closet, three men tossed and patted dough and then submerged it in an open fire-pit to make bolani and nani Afghani. Sweat beaded their temples. Their bodies moved as if in hypnotic dance.

Something about the scene, though exotic, evoked home. He thought, then, of Clarissa; her name came into his mind, and immediately he felt a tightening in his chest. He thought of her neck, and her long waist. He thought of her voice floating from the bathroom, the door open but she unseen, bent over the sink or patting dry her face, telling him a story from her day. He always found that to be the most intimate of moments— to be with a woman in early evening, lying on a bed, listening to her voice coming from within the bathroom as she brushed or washed away the soil of the hours before. He closed his eyes and rubbed his forehead and saw a fleeting image of his wife. Clari, Clari, Clari.

How had this amazing thing even happened to him, sharing a home again with a wife? He still wasn't sure. He'd been widowed twenty-two years ago, losing Mariana when Ruby was only six. He'd never planned to marry again, throwing all his energy first into being a single parent and then into his work. They'd met at a party. Clarissa was an urban historian teaching at Columbia. Whoever had casually introduced them— he couldn't remember that detail— had noted that she'd recently finished a paper on historic housing patterns in Manhattan. He hadn't been sure what that meant, but he'd immediately liked her smile, so he'd blundered forward, saying he'd noticed from his work with refugees how people arranged their living spaces even among war rubble, when you'd think shelter would be their only concern. A hierarchy developed, he'd gone on. Desirable housing locations arose in ways indiscernible to average outsiders, based on issues such as position relative to the main entrance and the water supply as well as proximity to certain families once considered more powerful. Some tents, he said, were erected a few inches further from their neighbors than others; this sign of status was noted— and accepted— by the camp inhabitants. It all happened without any apparent discussion, so that even when no one had any money worth mentioning, socio-economic groupings occurred.

As he was saying all this, talking almost without breathing just to keep her from walking away, he was really noticing her energy, her way of standing, the look in her eyes, her hair, and again, her smile.

Less than a year later, they married. It felt crazy, unexpected, and right. When they met, he was in the middle of the three-months-in, three-months-out rotations to Kabul and Islamabad. At first she'd been fine with it, but last year she'd offered— as if cupping her words in her hands and holding them out for him to see— that she wanted him to stop. She was careful, so he knew it was still his choice. But he also knew what she thought. It had become too dangerous. The separations were too long; he had a home to return to, and they had a life to build, and too little time.

So he'd agreed to the request she hadn't quite voiced; he was doing his last rotation. He would celebrate his fiftieth birthday at home in three months and then stay there through the next birthday, and the one after that.

And she seemed glad, but she was edgy still, maybe even more so when he'd agreed to quit, thus tacitly acknowledging the dangers. He'd detected it in her voice when they'd spoken a couple of hours ago by phone, as he began his morning, as she headed into sleep.

" There was a bombing in Islamabad a few hours ago," she'd said.

"Yes, I heard."

"Skip going there. Just come directly back."

"I'll be fine."

She made a sound that indicated skepticism. "I feel like a military bride, Todd. And what are we doing still there? Really, at this point?" "Helping people who need it." "That sounds so damned sanctimonious," she murmured.

"I'm sorry. But I have to finish up properly. For them. For me."

The line went silent for a moment. "Have they named your replacement yet?" she asked.

"Not yet."

"But they will, yes? You won't offer to stay on for one more rotation?"

"No, Clari. No."

She released a noisy sigh of air into the phone receiver. "Okay, then," she said. And she tried— they both did— to lighten the conversation, to talk about smaller things. But it didn't work; he felt the space gaping between them and knew she did too by her tone when she told him she loved him. He repeated it back, and they said good-bye.

Now he realized he wanted to meet Zarlasht's needs because he couldn't meet Clari's. Illogical, of course. But it was as if showing kindness to Zarlasht could make up for hurting his wife, one in exchange for the other. He needed to consider Zarlasht independently. He would try, on the walk back, with his ice cream.

But the line, Todd noticed, did not seem to be moving, though the vendors were bent over their sweet, cold tubs. "Ice cream is popular today," he said to the man in front of him, speaking in Pashto.

The man turned toward Todd. He was about twenty-five years old. He wore a blue-gray turban and a brown vest over his salwar kameez, and his eyebrows were unusually thick, like angry storm clouds hovering over his eyes. "It is the best ice cream in Kabul," he said in a way that seemed too serious, so weighted that Todd grinned, thinking for a second he must be kidding.

Then the man turned abruptly away, leaving Todd to stare up at the high, teasing blue of the sky and think about how Afghanistan, even after all these years, had remained just beyond his reach of comprehension. While this concerned him occasionally, it also inspired him and was, in fact, something he loved: the rich, unknowable quality of living here that made his own life feel so much more consequential. A rush of gratitude flooded him, warming his stomach, making him smile faintly. And this was exactly the expression on his face at the moment of the improbable crack of thunder that preceded the dropping of two glass ice-cream cups, and then the silence.