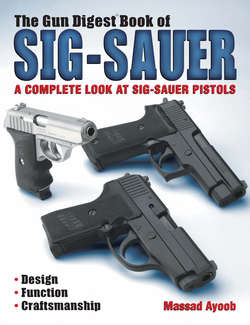

Читать книгу The Gun Digest Book of Sig-Sauer - Massad Ayoob - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

The SIG P220

The SIG P220

A writer owes his readers a disclosure as to his biases toward this and his prejudices against that. Let me open this chapter by confessing that the P220 is my very favorite SIG A pistol, and indeed, one of my all-time favorite handguns. Extraordinarily accurate, very reliable, and easy to handle and shoot, one of the P220’s cardinal attributes is the cartridge for which it is chambered: the .45 ACP.

The gun was introduced in 1976, the first of the SIG-Sauer line. Essentially designed by Schwetzerische Industriale Gesselcraft and manufactured by Sauer, it was chambered initially for the 9mm Parabellum cartridge and then almost immediately for .45 ACP and .38 Super for the American market. The 9mm P220 was immediately adopted by the armed forces of Japan, and of Switzerland, where it remains the standard military sidearm of Europe’s safest and most neutral country.

In 1977, Browning contracted with SIG-Sauer to produce the gun under their name as the BDA (Browning Double Action). It was introduced as such to the American market, where it received a mixed welcome. The gun experts loved it, instantly appreciating its smooth action, good trigger, reliability, and ingenious design. The purchasing public was less enthusiastic. They associated the Browning name with traditional, Old World guns crafted of fine blue steel and hand-rubbed walnut. Here was a modern pistol with flat gray finish and checkered plastic stocks, with an aluminum frame and a slide made of metal folded over a mandrel. It was as if Jeep had produced a fine four-wheel-drive vehicle under the aegis of Rolls-Royce: though the quality and function were there, the “look,” the cachet, were not what the buyers associated with that particular brand image.

The dust cover of P220 ST is grooved to accept accessories such as this InSights M3 flashlight.

Before long, SIG had decided to import the guns into the United States on their own and under their own name, establishing SIGARMS in Virginia. (Much later, SIGARMS would move to Exeter, New Hampshire.) It was at this point that SIG sales apparently took off. If the public would buy a machine that was rugged and precision-made, but not fancy, from Jeep but not from Rolls-Royce, then the same public would buy a rugged, precision-made but not fancy P220 that was marked SIG-Sauer instead of Browning.

Below is the author’s Langdon Custom P220 ST. Stocks are by Nill.

The Huntington Beach, California Police Department adopted the BDA in .45 ACP and had great luck with it. Their experience was widely publicized in both gun magazines and law enforcement professional journals. In the late 1970s, only a minority of American police carried semiautomatic pistols. Many gun-wise cops wanted auto pistols and didn’t trust the 9mm ammo of the day; they wanted .45s. Until the P220, the only gun that fit the bill was the Colt 1911 type pistol. Some forward-thinking departments adopted the Colt – LAPD SWAT, several small departments in California, a couple of county sheriff’s departments in Arizona – and many more made the Colt .45 optional. However, the mainstream of American police decision makers were leery about authorizing their personnel to carry a pistol that was perpetually cocked, and some worried that having to manipulate a safety catch would get in the way of a quick response when the officer needed it. The Browning BDA was obviously the answer, and changing its name to SIG P220 didn’t change that answer. When the BDA as such was discontinued, Huntington Beach recognized that the P220 was exactly the same gun, right down to complete parts interchangeability; they bought P220s and used them interchangeably with the BDA pistols already in hand.

Virtually straight-line feed is a key to the P220’s famous reliability, especially with hollow-point ammunition.

Police interest in autos was soaring. One sore point was that Americans habituated to American-style guns wanted a magazine release that worked quickly with a push-button behind the trigger guard. The BDA and the first SIG-Sauers had the European style magazine release, a spring-loaded securing clip at the heel of the butt. Police firearms instructors tended to be the department gun buffs, familiar with the 1911 and similar pistols from their time in other provinces of the world of the gun, and they clamored to SIG-Sauer for a pistol that ejected its magazines in the fashion to which they were accustomed. After all, speed of reloading was seen as one of the cardinal advantages of a semiautomatic pistol over a revolver; it was natural for the cops to want the fastest magazine release and therefore the fastest emergency reload possible.

SIG-Sauer listened and responded. In the early 1980s, they redesigned the P220 with an oval, grooved button behind the trigger guard to dump the magazine. While they were at it, they changed the shape of the grips, bringing the lower rear of the grip frame backward into an arch that widened toward the bottom. It filled the hand more substantially than the thinner and flatter-backed grip shape of the original P220. The change was analogous to Colt’s switch in the 1920s, at the request of the U.S. Army Ordnance Board, from the flat-backed mainspring housing of the original 1911 pistol to the arched housing of the 1911A1.

It was what the cops wanted, and SIG P220 sales skyrocketed. The .38 Super had never been popular in America except for a brief period between its introduction in the late 1920s and when it was eclipsed by Smith & Wesson and Winchester’s joint introduction of the .357 Magnum revolver and cartridge. Only a few hundred .38 Super BDAs had been sold, and the caliber remained similarly moribund in the P220 configuration. While all P220 sales to the world’s military had been in the 9X19 NATO chambering, I’m not aware of a single American police department that adopted either the BDA or the P220 in 9mm or .38 Super (though Secret Service would look very closely at the latter). No, it was the .45 that American cops wanted.

With the changed grip shape and side-button release, the new gun was designated the P220 American. Accordingly, the original would become known as the P220 European or P220-E. Its sales in the U.S. would wither and die, with the American style roaring forward in sales to police and civilians alike; the 1911’s influence was even stronger in the latter sector of the U.S. handgun market.

Countless police departments, including the state troopers of Texas (who used it exclusively) and of Arizona, adopted the P220. The latter gave their highway patrolmen the choice of the eight-shot .45 P220 or the 16-shot 9mm P226. The overwhelming majority chose the P220 .45.

The accessory rail of the P220 ST is a great addition.

This standard P220 has earned the author’s smug smile. The one-hole group in the neck of target was made by 12 200-grain bullets fired in less than 20 seconds from 7 yards, including a reload. The tight cluster in target’s chest was from one-shot draws averaging around a second at 4 yards. This is proof of the P220’s shootability.

In 1988, the FBI for the first time authorized rank and file agents to carry semiautomatic pistols. At first, only two guns were authorized, both in 9mm: the SIG and the Smith & Wesson. Shortly thereafter, the forward-thinking head of the Firearms Training Unit at FBI’s Academy in Quantico, John Hall, convinced the Director to also approve the .45 ACP in the same two already-approved brands of pistol. FBI agents rushed to purchase their own SIG P220s, which were both more compact than the all-steel Smith & Wesson Model 645 that had been introduced in 1983, and much lighter. The P220 .45 was the choice of Special Agent Edmundo Mireles, who had emerged as the hero of the infamous shootout in Miami, which had led to the Bureau’s approval of semiautomatics. Mireles had ended that gunfight with .38 Special bullets delivered to the head/neck area of the two cop-killers involved, and was clicking his revolver’s hammer on six spent cartridges at the end of the drawn-out death duel.

IDPA Stock Service Pistol Master Steve Sager tries his hand with a P220. The spent casing visible above his head shows immediacy of the shot, but the muzzle is still on target.

P220 Attributes

The P220 always fit most hands well. It always had good sights compared to most of its competition. And, of course, there was the reliability factor. The gun was and is extremely reliable.

Whether steel- or alloy-framed, P220s are accurate with a variety of ammunition. +P should be used sparingly in aluminum-framed guns.

This LFI student has topped his class more than once with his ergonomic SIG P220 American. He is about to fire all center hits strong-hand-only…

But the gun had other advantages, too. High among these was the double-action first shot mechanism. Police chiefs had been leery about carrying cocked and locked guns. The long, heavy double-action pull required to initially unleash the firepower of the P220 was much like that of the revolvers that were so much a part of their institutional history. Cops in general and police chiefs in particular were and still are much more comfortable with a double-action like the 220.

…and does the same weak-hand-only, with good recoil control. Note spent casing passing the target to the right of the gun.

Most 1911 pistols of the period were not “throated” by their manufacturers to feed wide-mouth hollow-point bullets, the choice of most police and gun-wise private citizens. Engineered with a nearly straight-line feed, the P220 was reliable with almost every hollow-point bullet.

The P220, even with an aluminum frame and powerful .45 ammo, is comfortable for a week of intensive firearms training.

There was also the accuracy factor. The SIG-Sauer pistols are famous for accuracy across the board, but the P220 may be the most accurate of them all. I have twice put five rounds from a P220 into one inch at 25 yards. Both times, the ammunition was Federal 185-grain JHP, which the manufacturer used to mark on the box as “Match Hollow Point.” It was certainly truth in advertising. One of those guns was a well-worn P220 European, the other, a brand new P220 American.

Almost every credentialed tester has noted the P220’s extraordinary accuracy. In his book The , defensive firearms 100 Greatest Combat Pistols expert Timothy J. Mullin had this to say about the P220. “All SIG pistols and products are fine weapons, but this one is particularly impressive. My groups were so remarkable that I tested again at 25 and at 50 yards – and the results were just as superb. I placed five shots into a little more than 2 inches, and I pulled one of those shots. Four shots went into roughly 1-1/4 inches.” (1) A fan of SIG’s compact single-stack 9mm, Mullin added, “Although the P220 is not as good as a P225, I would rate it the top weapon that I tested in .45 ACP.” (Mullin’s emphasis.) (2)

My friend Chuck Taylor is one of the leading authorities on combat handguns and the author of a great many articles and multiple books on the topic. When he wrote the fourth edition of The Gun Digest Book of Combat Handgunnery he had the following to say about the P220 .45.

“First appearing almost two decades ago as the Browning BDA, the P220 in its current American version is regarded by many as being the state-of-the-art .45 auto. Indeed, its popularity is exceeded only by that of the Colt M1911 Government Model, whose king-of-the-hill status the P220 is now seriously challenging, especially in law enforcement circles.” Chuck continued, “The P220 is a simple design, perhaps as simple as a handgun can be and still work. Its human engineering is excellent because, like its baby 9mm brothers, the P225 and P226, its controls are placed where they can be readily operated, something exceptional for a DA auto. Furthermore, its mechanical performance leaves nothing to be desired. It is probably the best DA self-loader around…In summary, the P220 is an excellent example of how good a DA auto can be. As such, it is well worth its not-inconsequential price and clearly a handgun upon which one could with confidence bet his life.” (3)

Current magazines make the P220 reliable with eight in the stack and a ninth in the launch tube.

Many double-action semiautomatics had a DA trigger pull that was heavy, rough, or downright lousy. The SIG’s double action pull was excellent, probably “best of breed.” It was the standard by which the competition was judged. Once the first shot had been fired, it went to single-action, where the trigger press was a clean, easy 4 to 6pounds or so. The distance the trigger had to move forward to re-set the sear was just enough to give a buffer against unintentional discharges under stress, but not so great that it appreciably slowed down the shooter’s rate of fire.

With a 4.41-inch barrel, the SIG was a little longer in that dimension than the 4.25-inch Colt Commander, but more than half an inch shorter than the 5-inch Government Model. The Commander, originally introduced in lightweight format in 1949, weighed 26.5 ounces unloaded and held the same number of .45, .38 Super, or 9mm rounds as the P220. Later offered as the steel-framed Combat Commander, the Colt put on an additional 10 ounces in that format. The lightweight Commander was dubbed by one of its greatest advocates, Col. Jeff Cooper, as “a gun designed to be carried much and shot seldom.” Most who had fired it considered it much more unpleasant to shoot than its big brother, the full-sized, all-steel Government Model.

This is the double-action-only (DAO) version of the P220 .45, carried daily by a Chicago cop. Note the absence of decocking lever behind the trigger guard. Grips are by Hogue.

Thus it was that the cops and the shooting public were delighted to discover that the SIG P220, which like the lightweight Commander had an aluminum frame, wasn’t anywhere near as difficult to shoot as the alloy-framed Colt. A major reason for the perception of the Commander’s vicious recoil was that, until the 1990s, its manufacturer furnished it with a short, stubby-tanged grip safety that bit painfully into the web of the hand whenever the gun was fired.

By contrast, the P220 was much rounder and more friendly to the hand. Nothing bit the shooter. In the P220, the low-pressure .45 cartridge simply drives the slide back with a gentle bump. Even though the slide of a 1911 pistol sits lower to the hand and should jump less since it has more leverage, anything that causes pain to the hand will magnify the shooter’s sense of recoil, and increase his likelihood of flinching and blowing each shot.

The P220 weighs a tad less than a lightweight Commander, 25.7 ounces unloaded. Yet most officers found it at least as pleasant to shoot as the full size 1911A1 in the all-steel configuration, which weighed some 39.5 ounces. Only when a custom gunsmith (or, beginning in the 1990s, the manufacturers) put a beavertail grip safety on the lightweight 1911 did it become as comfortable to shoot as a P220, and allow the shooter to take advantage of the reduced muzzle jump potential afforded by its lower bore axis. However, none of this changes the other SIG attributes that made the P220 a favorite.

The next time someone tells you that you can’t control a SIG .45 because it has a higher bore axis than a 1911, remember this photo. The spent casing of full-power .45 load is sailing past her cap brim, yet slender Patricia Sager has kept the P220 ST on target.

A P220 loaded with nine rounds of .45 Hydra-Shok is a reassuring companion for police officers and law-abiding armed citizens alike.

A lightweight service pistol is especially important in law enforcement. The duty belt carries a great deal of equipment. The author has seen duty belts weighing in the 15- to 20-pound range once festooned with multiple handcuffs, a full-sized baton, heavy flashlight, portable radio, and ammunition. The pistol is a significant part of the load, and any reduction in weight is appreciated. The weight of the duty belt is one reason why back problems in general and lower back problems in particular seem to be an occupational hazard of the street cop.

The pistol in its uniform holster rides near the edge of the hip, and on some individuals with some uniform designs, can directly contact the ileac crest of the hip. The potential for fatigue and discomfort is obvious. Reducing the weight of the duty .45 from 39.5 ounces to 25.7 (the same round-count of the same ammunition adds the same weight to either) results in a 13.8-ounce weight saving – almost a pound – at a critical point.

Now, let’s look at plainclothes wear, whether in a detective assignment or off duty. The dress type belt, even a dress gunbelt, does not support the weight of the holstered gun as efficiently as the big, 2-1/4-inch-wide Sam Browne style uniform belt. A heavy gun becomes all the more noticeable. For generations, officers carried little 2-inch .38 caliber revolvers as off-duty guns, simply for their light weight and convenience. However, they paid the price of a caliber that offered minimum acceptable power, especially when the ammunition was fired from a short barrel. They paid the price of a reduced in-gun cartridge capacity, only five to six rounds. They paid the price of a gun that kicked hard despite that minimum acceptable power level, and a gun that was difficult to shoot fast and straight, particularly at small targets or at longer range.

Now, the P220 .45 gives the plainclothes officer a much more attractive option. While not so small overall as a snubby .38, it is very flat. It fires the much more powerful .45 ACP cartridge, but despite its greater power it kicks less and is more pleasant to shoot than most snubbies. It is about the same weight as the six-shot Smith & Wesson Model 10 or Model 64 Military & Police revolver with a 2-inch barrel. And, of course, it is much faster to reload, and its flat magazines are much more discreet and comfortable to carry than speedloaders for a revolver when concealment is the order of the day.

With an inside-the-waistband holster and proper clothing, the P220 virtually disappears into concealment. With a well-designed scabbard riding on the outside of the belt, it is almost as easy to hide. The fact that a single pistol with which the officer is intensively trained could be used on or off duty, in uniform or in plainclothes, is another big factor in the P220’s favor when police departments look at purchasing new sidearms.

The P220-E is a particular favorite of mine. Back in the 1980s I discovered that, just as the flat housing of the original 1911 pistol fits my hand better than the arched housing of the later A1, the slimmer, flatter-backed shape of the original SIG P220 grip frame seemed more comfortable in my hand than that of the later P220.

However, there is another reason I was partial to the P220-E. In the Northern New England area where I have spent my now almost 30 years as a police officer, it is not uncommon for the wind chill factor to bring the temperature to 30 degrees below zero or worse in deep winter. This requires heavy gloves. I had found over the years that bulky gloves could sometimes cause a shooter to unintentionally activate a side-mounted magazine release button. This did not occur with a gun that had a butt-heel magazine release, like the P220-E or the BDA that preceded it. I special-ordered a P220-E .45 from SIG, and was told that it would probably be the last one brought into the country. (I’m told that the firm later changed its mind and brought in a few more in dribs and drabs, as the limited stateside demand warranted.)

This became my favorite winter gun for many years. On patrol when department regulations allowed it, and on my own time always, the P220-E was part of my cold-weather gear. Since the P220 American’s magazine was the same as the European’s but with four engagement holes cut in the sides (two on each side, to mate with the side button mag release, which could be easily converted for left hand use), the new magazines fit my old gun. The reverse was not true. This was because the European style mags did not have a cutout in which the side-button mechanism of the P220 American could engage. Much later, when SIG’s current eight-round mags came out with bumper pads running front to back, it turned out that they would not be compatible with the European or BDA magazines. This was because the rear of the extended bottom of the magazine could not engage the butt heel release device.

That particular P220-E is now in the hands of a good friend who needs it more than I do, but I cherished that pistol and look forward to having it back one day. It was modified over the years by pistolsmith John Quintrall, a master of the SIG-Sauer who was guided by a very knowledgeable old hand, the late Jim Anderson. The action was butter smooth in double-action and super sweet in single. John fitted Trijicon night sights (there tends to be more dark time in the winter, and remember, this was my “winter gun”), and after I shot it so much the accuracy started to fade slightly, he fitted a Bar-Sto barrel. It turned out to be the one case in which I had a Bar-Sto installed in a pistol, and accuracy did not improve. There was nothing wrong with the Bar-Sto; it simply couldn’t improve on the already superb SIG-Sauer barrel. A new SIG barrel, I expect, would have given me pretty much the same results.

The butt-heel release is a second or so slower for speed reloading than the American style. Certainly, there are situations in which a second can make all the difference; Americans are acutely conscious of that, and this is why SIG makes the American style P220. However, I found that with heavy snowmobile gloves on, the cruder gross motor movements of pushing back the latch with the free hand thumb and ripping the spent magazine out were actually more easily accomplished than finding the magazine release button with a thumb encased in a heavy glove that blunted the sense of touch and limited the thumb’s range of movement. In short, in heavy winter garb, I was able to reload the P220-E as fast, or very slightly faster, than the P220 American.

The P220’s “Other” Calibers

While we Americans have directed most of our attention to the .45 caliber P220 – after all, the .45 ACP has been called “the classic American cartridge” – the P220 has racked up an enviable reputation in its other calibers as well. On more than one occasion I’ve taught in Switzerland. There are some police departments there that issue the P220 in 9X19mm, though the higher capacity P226 seems to be far more common in Swiss law enforcement. More to the point, though, the P220 9mm has been the national standard Swiss military sidearm for many years.

Switzerland is a nation of shooters. It is well known that the Swiss militia constitutes the entire able-bodied male population of the nation (Swiss women may join voluntarily, though it is not required) and that all are issued what may be the finest assault rifle in the world, SIG’s Stg.90.

The Sturmgewehr 90 is a superb, state-of-the-art assault weapon. However, the Swiss public takes marksmanship as one of their national sports, and most of that marksmanship is done with military weapons of various ages. Virtually every Swiss village I passed through had a 300-meter rifle range, and the ranges stay in constant, heavy use. In rifle matches, the ancient Schmidt-Rubin 7.5 mm straight-pull bolt-action rifle is still used to compete against the ultra-modern SIG Stg. 90.

I say all this to lead up to a point. The Swiss have a lot of pistol matches, too. As you might expect they fare well in ISU (International Shooting Union) Olympic-style target sports, and also have a well-established contingent of practical shooters who belong to IPSC (the International Practical Shooting Confederation). However, a good deal of their handgun competition also involves national standard military weapons. Over the course of the 20th Century, Swiss military-issue handguns have included such fabulously accurate weapons as the Luger pistol, the exquisite SIG-Neuhausen P210, and only since the latter quarter of that century the SIG P220 9mm.

The P220 tends to give consistently good accuracy with most .45 ACP ammunition. These groups were fired from 25 yards.

And there was one thing I couldn’t help but notice. The 9mm P220 keeps up with the famously accurate P210! This, clearly, is testimony to the P220 9mm’s match-grade accuracy, which is achieved without compromising total reliability, even with some very old pistols that have fired countless thousands of rounds over the decades.

The .38 Super P220 did not prove popular at all. In the United States, at least, it had always been a specialist’s cartridge. Handgun enthusiasts appreciated its flat trajectory. Handgun hunters appreciated its inherent power. Cops in the Depression years liked its deep penetration against criminals’ “bullet-proof vests” and automobiles of the period. But no one liked its mediocre accuracy.

The reason was that the .38 Super was not a true “rimless” auto pistol cartridge, but instead featured a semi-rimmed case. From its introduction in the late 1920s until the coming of the SIG-Sauer engineers, Colt and every other manufacturer cut the chambers of their .38 Supers to headspace on the rim. The chamber in SIG-Sauer P220 in .38 Super was cut to headspace at the case mouth, which allowed more consistent and solid chambering. Thus did the Browning BDA/SIG P220 become the first truly accurate factory-produced .38 Super pistol. The same headspacing was developed by gun barrel genius Irv Stone, the founder of Bar-Sto, and when put in 1911 target pistols resulted in the .38 Super cartridge’s renaissance in the shooting world, specifically in practical pistol competition.

It has been reported that the P220 has been produced in very small quantities in caliber .30 Luger. I cannot speak to its accuracy as I have never seen one, let alone tested one. I am not aware of any nation or agency that has adopted the P220 in that caliber. Thus, its accuracy remains an unknown quantity, at least to this author.

Idiosyncrasies

In earlier models, there were some specimens in .45 caliber which did not feed one particular cartridge in one particular situation. The round was the old “flying ashtray,” a short and very wide 200-grain hollow-point from CCI Speer, who called it at various times the Lawman load and the Inspector load. It was notorious for jamming 1911 .45 pistols. The SIG would normally feed it just fine, but with some of the seven-round magazines, if the pistol was reloaded from slide-lock, the short Speer 200-grain would take a little dip coming off the magazine’s follower and strike low enough on the feed ramp to cause a six o’clock jam.

Most simply got by with another brand of ammo. My own solution was to load my personal P220 with the eight of the flying ashtrays, one in the pipe and seven in the mag, and then load the spare magazines with some other type of JHP round. My P220 never failed to feed this infamous gun-jammer once it was loaded into the P220 and the first round was chambered.

Over the years, the problem has resolved itself with new designs. The current 200-grain CCI Speer .45 offering, the Gold Dot bullet, does not seem to have any problem feeding in late model SIGs. I think it’s a combination of the improved fourth-generation P220 .45 magazine, and better feeding characteristics of the Gold Dot 200-grain bullet compared to the conventional jacketed hollow-point which preceded it.

Chuck Taylor is a contemporary and observed the same thing. He wrote in his edition of The Gun Digest Book of Combat Handgunnery, “My P220 shoots very well indeed, with three-shot Ransom Rest 25-meter groups averaging slightly over 2 inches. I’ve also had no functioning problems whatsoever with the gun, although in some of the earlier versions, some problems were reported with several styles of JHP bullet. SIG Sauer, to their credit, immediately relieved the front of the magazine body to allow better bullet clearance, which solved the problem nicely.” (4)

P220 .45 Magazines

About those four generations of P220 .45 magazines. They go like this:

First generation: Seven-round BDA/European style. Will only work in P220s with butt-heel magazine release.

Second generation: Seven-round P220 American style. Will work in American, European, and BDA model .45s.

Third generation: The so-called “DPS Magazine.” A P220 American mag with the same flat-bottom floorplate as the first two generations, but modified in spring and follower to take an eighth round. These were created for the Texas Department of Public Safety when they adopted the P220 American .45, and reportedly, Texas DPS had great success with them. Personally, I have never trusted a magazine designed for seven rounds, which then had an eighth forced into it; we fool Mother Nature at our peril.

The eighth cartridge in a magazine originally designed for seven put the rounds so tightly in the stack inside the magazine that there was no flex in the spring. This meant that if the P220 was reloaded with the slide forward, either in administrative loading getting ready for duty or in a tactical reload with a live round already in the chamber, the shooter really had to slam the magazine in to make certain that it locked in place. After experimenting with the DPS magazine, I went back to the earlier ones. Police had already cautiously waited for decades to switch from revolvers to autos because of fears of reliability. Their mantra had been, “Six for sure beats 14 maybe.” My reasoning as to P220 magazines was similar: “Seven for sure beats eight maybe.”

Fourth generation: Eight-round current production. These are unquestionably the finest .45 caliber magazines ever made for the P220 pistol. They are crafted of stainless steel, always a bonus when a gun and its spare magazines are carried in hostile environments, which can be rain and snow attacking guns holstered outside the clothing, or heat and humidity and salty, corrosive human sweat when the pistol is carried concealed. Moreover, the Gen Four SIG P220 .45 magazines are extended very slightly at the bottom, into a hollow floorplate. This does two good things. First, the buffer pad on the floorplate makes magazine insertion easier and more positive, especially under stress. Second, the added space inside the floorplate allows the eighth round to be stored there without too rigid a spring stack or undue pressure on the magazine springs. These are what I now carry in my P220 .45.

A word on aftermarket magazines. I normally trust only the magazines the gunmaker sells with its firearms. For the P220 .45, I trust Sauer-made SIG magazines and I trust Mec-Gar magazines. This may be seen as a redundancy, since Mec-Gar produces SIG’s magazines for them. The currently imported Novak’s P220 magazine seems to work well. ACT in Italy produces it. While marketed as an eight-round mag and having an extended floorplate, I’ve nonetheless found that some will comfortably hold all eight and some are better carried with seven rounds, at least when new.

Many shooters have found full P220 .45 mags hard to unload, at least for the topmost cartridge or two. Here’s the secret. Hold the loaded magazine in one hand and pinch the thumb and forefinger of the other hand beneath the nose of the cartridge on top, applying upward pressure. Now use the thumb of the magazine-holding hand to push the cartridge forward. It will come out much easier. Repeat if necessary for the next cartridge or two; after that, spring pressure will be relieved and the thumb alone will be able to slide the rest of the rounds out easily.

Variations

Though many considered the P220 a compact handgun, many who owned them wanted one even smaller for deeper concealment. This wish was granted by SIG in the form of the excellent little P245, a pistol that differs sufficiently from the P220 that it is treated separately in this book.

Stainless steel P220s have also been produced. Basically the same gun as the original, but heavier, they differ only in handling qualities and, of course, in adding one more option of corrosion resistance to the many finishes which are discussed in the segments of this book devoted to accessories and customizing.

The first of these guns was the P220 Sport, introduced to the public in 1999. I was at a conference of the firearms press conducted by SIGARMS in conjunction with the NRA Show and Annual Meeting in Philadelphia in 1998, where we were given a chance to play with advance versions of this gun.

Fitted with a long muzzle weight-cum-compensator, and with an all-steel frame of stainless alloy, this handsome pistol sports a 5.5-inch barrel and weighs some 44 ounces. With the added weight and the comp, recoil and muzzle jump are greatly reduced. The exquisite accuracy of the earlier P220s was clearly present in this .45. It was introduced with grooves on the dust cover (front of frame) to accept additional weights and other accessories proprietary to SIGARMS.

I liked the gun, but found it a bit big for my tastes and needs. Like many, I just said, “Make us a regular P220 with this frame, and groove the dust cover to accept more common accessories, like the M-3 flashlight.”

SIG listened. The 21st Century saw the P220 ST, exactly the gun described above. Though the first models had reliability problems (and, I thought, below-P220-standard accuracy), this was traced to the use of a stainless steel barrel. SIG solved the problem by installing their conventional chrome molybdenum steel barrel within the stainless slide.

Now, we had a truly meaningful option within the P220 line. There were those of us accustomed by years of wearing Colt Government .45s that weighed 39 or so ounces, and didn’t mind the fact that this was the weight of the all-steel P220 ST. In return, we got the recoil reduction and added durability that came with all-steel construction. Before, SIG engineers had been leery about recommending +P .45 ACP ammo for these guns. I saw very few aluminum P220 frames crack after continuous shooting with +P, which brings the ACP up to a power level comparable to a full-power 10mm Auto cartridge, which is infamously brutal to even full-size .45 caliber guns. With the ST variation, my sources at SIG tell me that they just don’t see a problem.

References

1. Mullin, Timothy J., The 100 Greatest Combat Pistols, Boulder, CO: Paladin Press, 1994, P.315.

2. Ibid., P. 316.

3. Taylor, Chuck, The Gun Digest Book of Combat Handgunnery, Fourth Edition, Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 1997, P. 224-225.

4. Ibid., P.225.