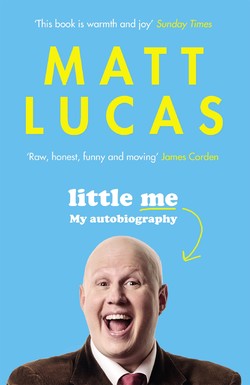

Читать книгу Little Me - Matt Lucas - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеC – Chumley

The bespectacled, frizzy-haired Chigwell housewife stood in front of us, recounting her life story. She talked about school, her first job, how she met her husband. It was all going swimmingly.

‘And then I was raped.’

We gasped.

‘Well, no, I wasn’t, but I wish I had been.’

Another gasp.

She continued her loose, improvised monologue for another minute or two, but we were now too shocked to laugh. As she came to an end, we applauded uncertainly, then turned as one to Ivor, who was running this stand-up comedy class.

‘Thank you, Pamela. Um, very good. Yes.’

Not much seemed to faze Ivor, but it took him a moment to work out how to respond.

‘Some nice observations there. If I had any criticism, I would say that, while there are no taboos in comedy as such, the “rape” line did take us all a bit by surprise. I felt that perhaps we found it hard to laugh again after that.’

We nodded our heads in agreement.

Summer 1992. Like some of my friends, I had opted to take a year out after my A levels. Unlike my friends, however, many of whom were travelling around the world, I had decided to launch myself on the London stand-up comedy circuit.

My teenage passion for performing had continued unabated. The year after my Edinburgh Festival experience, I’d bagged a background role in a West End play. Two years after that, at sixteen, I joined the National Youth Theatre – which mainly did Shakespeare and more serious stuff than the NYMT.

In the National Youth Theatre I had met a funny guy called David Williams, who was a few years older than me. (I’ll tell you more about that later, of course.) David and his friend Jason Bradbury were doing ‘open spots’ on the comedy circuit – unpaid five-minute slots for aspiring acts – and I’d follow them around. Sometimes they went down a storm; other times you could almost see the tumbleweed – but I thought they were hilarious and I dreamed of being a stand-up comic too.

Ivor Dembina’s stand-up comedy course was incredibly helpful. Not only did we get to write and test out routines on each other, building them up week by week, but Ivor also taught us how the alternative comedy circuit worked: no sexist, racist or homophobic material, don’t go over your time, don’t nick anyone’s gags and don’t badmouth other acts because you don’t know who’s friendly with who.

The only sticking point was that I had an idea for a character that I wanted to try out, but Ivor wouldn’t let me. His reasoning was that we should be ourselves onstage. I was happy to do that on the course, but I knew that, as soon as I was playing the circuit itself, I would appear in character.

There were a few character comedians on the circuit and they were always my favourites to watch. As much as I enjoyed the observational comics, I had no desire at all to be one. I didn’t want to walk out and do gags about being bald and I didn’t have a girlfriend to talk about. I wanted to perform – to show off – but I wanted to do it in the guise of someone else.

And I had a character in mind – well, not really a character, more just a silly voice at that stage. Throughout my childhood I would both entertain and ultimately rile my mum and brother by doing silly voices. I’d often fixate on one and then get consumed by it for weeks. For a time I couldn’t stop being Jack Wild in Oliver! After I returned from the Edinburgh Festival I was Miss Jean Brodie.

‘Okay, that’s enough now!’ Mum would say, her patience wearing thin once again, especially if I was supposed to be studying for my bar mitzvah or mowing the lawn.

I had been a massive fan of Harry Enfield and had loved a spoof South Bank Show documentary he’d made, called Norbert Smith – A Life. Enfield played the subject – formerly the defining young actor of his generation, rather like Lord Olivier, and now a sweet, befuddled old man.

There were various interviewees in the film – characters who had supposedly worked with Sir Norbert and who shared their recollections. One of them – played by Moray Watson – was called Sir Donald Stuffy, seemingly a nod to a couple of other famous theatrical Donalds: Sinden and Wolfit. During his scenes he told long-winded anecdotes and appropriated the names of other actors. For instance, Dame Anna Neagle became ‘Dame Anna Neagly Weagly’ and Rex Harrison was ‘Rexipoo Harrison’. He was the ultimate ‘luvvie actor’ and even though he only appeared onscreen for a minute or two, my brother Howard and I thought he was the funniest thing in the show.

I’d impersonate all the characters in the programme, but whenever I did Sir Donald Stuffy’s voice it seemed to amuse Howard the most. I did it so often that it wasn’t long before I stopped quoting lines from the programme and started using him as a vessel for my own jokes instead.

Gradually I built up a biography for the character – shows he’d been in, his friends, his agent, where he lived, until it felt like my own. Howard proposed the name Sir Bernard Chumley, which stuck.

If Ivor wasn’t too sure about me appearing in character – at least, on his course – my mother had greater concerns. If I was going to be taking a break from full-time education and still living at home, I’d need to be contributing towards my upkeep. I couldn’t argue with that and I knew it would probably be a long time before I’d be getting paid to perform, so I started to look for a day job.

Previously, while doing my A levels, I’d added to my pocket money by working as a babysitter. I didn’t get much work – most parents told me that they would rather have a girl minding their children – but after I placed an advert in the synagogue magazine, one couple, Clive and Michelle Pollard, contacted me and I started looking after their kids on a Saturday evening.

Clive manufactured and imported football merchandise – like those mini-kits you see in car windows – and had the contract to sell his wares at Wembley Stadium and in various football club shops. He had also just won the contract to run the shop at Chelsea Football Club. I was Arsenal through and through, but, keen to fund my stand-up career, give my mum some money and aware that jobs were hard to come by in the recession-hit Britain of 1992, I asked Clive for a job.

‘We’re looking for an assistant manager,’ he said.

‘Yeah, I can do that.’

‘You’re only eighteen.’

‘Well, I’m old enough to be trusted with your kids,’ I replied. He said it was a good enough answer to get me a job, and so it was agreed that I would help set up the shop and work there during my year off.

The job kept me busy through the day, and during the evenings I set about launching my comedy career in earnest.

I began by writing a dreadful routine at the desk in my bedroom. The set took the form of a long, rambling theatrical anecdote about events at a party Sir Bernard had attended. He name-dropped frequently – but often got the names a bit wrong – Bruce Wallace, Mel Gibbons – and invariably I would use the name-drop simply as an excuse to do an impression of a particular celebrity – Jimmy Savile, Jim Bowen. I had no idea what I was doing and, in truth, my desire to perform and be acclaimed for it outweighed any particular comedic message I wanted to deliver.

My meteoric rise was carefully planned. I would do my first open spot at the Punchlines in West Hampstead on Saturday, 3 October 1992. I would perform the following evening at the club for open spots that Ivor had recommended – the VD Clinic (which promoter Kevin Anderson said stood for Val Doonican). And then on the Thursday night I would crush it at London’s premier venue, the Comedy Store. In less than a week I would be a star. Job done.

What confidence. What delusion. But then I was only eighteen years old.

Actually I ended up having an unofficial first gig a few weeks earlier, somewhat spontaneously. David Williams and his friend Jason were performing at the Comedy Café in Rivington Street. On a Wednesday night the club traditionally featured a bunch of open spots. The first to arrive and put their names down on the list would get a slot. I had gone along with my friend Jeremy to watch David and Jason perform and, on learning that there was a space on the bill, couldn’t resist putting my name down, so eager was I to get on the stage – and also to impress David and Jason.

I was one of the last to go up. I didn’t have my costume. I had written my act down a few weeks before, but hadn’t actually learned it yet (not that it would have made much difference, devoid as it was of any actual jokes). I busked it, as they say. And it didn’t go down well.

Sir Bernard’s tale about the events at his showbiz soirée ended with his arse exploding and faeces landing on the faces of various celebrities . . .

‘There was shit on the ceiling, caca on the carpet, dump on the dining table, poo on the porcelain . . . I didn’t know where to look. And I turned to Felicity Ken-dell and I said “Felicity, you’ve grown a moustache” but she hadn’t – a bit of poo had deflected off the ceiling and landed on her upper lip!’

In my set I had contrived a reason for this arse explosion that involved Sir Bernard having been born in India and therefore being caught in some sort of ‘Anglo-Asian curry zone’. I know it doesn’t make any sense. I’m sure it didn’t then, either. But as soon as I mentioned about coming from India, some of the audience started shouting ‘Racist!’ I was taken aback. I hadn’t done an Indian accent or made any further comment, but the table of young men had had enough. I wasn’t quite booed off, but everyone in the room could hear the reaction. I hurried through to the end of the set and got off.

Jeremy and I left the venue quickly, my heart racing as I sat on the Tube back to Edgware station, trying to process what had happened. It was clear that I would have to make some big changes to my set before my first ‘official’ gig.

A few weeks later I turned up at the Punchlines club for my proper debut. I knew the place well, having been a regular punter there for a year or two. Despite being underage, I would flash my fake ID and make half a pint last the night as I watched some of Britain’s finest up-and-coming comedians take the stage.

I certainly hadn’t been shy in letting people know about the big event and much of the audience was made up of friends (and their friends and their friends etc.).

When it was my turn to appear, the compère gave me a warm introduction. I had a pre-recorded intro on tape, which featured some speeded-up music that I had found in my parents’ record collection, and me introducing myself in a bad Northern accent – ‘Live from Barry Island . . .’

Why would a theatrical raconteur be in Barry Island and why was a Northern voice introducing him? And why was I pretending to be a theatrical raconteur? I barely even knew what one was. I’m sure the audience had no idea, either. It made little sense.

It also wasn’t that funny.

But I needed to be onstage. Despite the confidence I’d got from those Youth Theatre appearances, I was still desperately unhappy, scared, freaked out by the events of my youth, by my paleness, baldness, fatness, gayness, otherness. Like many before me, and countless others since, I was convinced that becoming successful and achieving public recognition was the only way my sad story could end happily.

I was happy to use anything and everything I had in my pursuit. Sir Bernard was bald, though for much of the routine he proudly sported the wig that I had thrown in the cupboard a few years earlier.

The wig might have come out of the closet. I hadn’t – yet. But Sir Bernard was so gay that I partly hoped it wouldn’t occur to anyone that I wasn’t. He would do my coming out for me, I hoped. I wouldn’t have to say the words or live the life. I could hide in plain sight, at turns celebrating and mocking homosexuality, playing to both gay people and those who found gayness absurd, dancing nimbly backwards and forwards either side of the line.

Now people would laugh with me, not at me. I would control it.

The compère – Dave Thompson, later to find fame as Tinky Winky in Teletubbies – introduced me. The audience hollered loudly at my entrance and I sprinted on. I hadn’t considered how long the introductory music was (i.e. far too long) and, eager to fill the time, spontaneously broke into a wild dance, which drew laughter. Ever the fat, sedentary asthmatic, by the time the music came to an end I was breathless.

That night I wheezed and panted my way through my muddled little routine. Each lame joke was greeted with a supportive cheer from those who knew me, rather than a laugh. Those who didn’t know me would doubtless have been utterly bemused.

At the end of my act there were wild cheers. I took the applause – a little embarrassed, because I knew, despite the response, that it hadn’t worked on a comedic level. Dave came back onstage and the audience continued to applaud. He generously waited there and acknowledged the reception I was getting.

And what did I do? Well, because I am a bloody idiot, I stood behind him, signalled in his direction and did the ‘Wanker’ hand-sign.

Why did I do that?

I can only think that I was just trying to generate another laugh. I was eighteen years old and unprepared for – and giddied by – the audience’s applause. However, not only was my response unprofessional, it was also completely unwarranted, but that didn’t occur to me in the moment.

I got another laugh and went off.

Downstairs, in the backstage area, sweating, waiting to get my breath back, I accepted the congratulations of the other comics, but I knew that this hadn’t been a real victory. Half the crowd was already on my side. I’d shown balls – yes – but not much else.

The next act went onstage and then Dave appeared in the waiting area. He summoned me over and calmly asked me why I had called him a wanker onstage in front of the audience.

I gulped. I had no idea he’d seen the gesture. I stammered an apology. He told me, his anger coming to the surface, how I’d made a huge mistake, that comedians must never ever undermine each other like that onstage, that he had given me a great introduction and encouraged the audience to applaud me afterwards, that it was an incredibly selfish thing to do, that he was furious and that there was no place on the circuit for that kind of behaviour. If he told other people what had just happened, he said, I would never get booked anywhere.

What had I done? That was it. It was all over. My name would now be mud. People who hadn’t seen my act yet – who hadn’t heard of me – would know me by this story and this story alone.

He was apoplectic, but of course totally justified in his anger. I continued to apologise profusely. I told him I was completely out of my depth, that it was my first gig, that I’d been flustered and surprised by the audience’s response. Unsure of what to do, I had made a grave error. I was genuinely contrite. I felt awful to have put us both in that position, had learned an important lesson and would never do anything like that again. He accepted my apology and we shook hands.

Outside I was met by friends and acquaintances and praise was poured on me, but I was very shaken up and just wanted to go home.

The following night, I arrived for the next gig – at the VD Clinic, a dedicated open-spot show which took place every Sunday evening in the downstairs bar of the White Horse pub in Belsize Park.

I walked in and my face dropped. There in front of me was Dave Thompson, the compère from the night before. By chance he was hosting this gig too. Sheepishly I went and said hello and he was a complete gentleman, making no reference at all to the previous night’s incident. Onstage I was already calmer, wiser, more focused. The audience had been primed for an evening of new acts and it felt like a more natural environment for me. To my surprise, the set went down well. Afterwards Dave congratulated me. I thanked him and apologised again and again until he told me I could stop. Over the next few years I often found myself on the bill with him and we always laughed about our first meeting.

So my third gig was a success – or rather, I had got away with it – but the following morning I phoned Don Ward at the Comedy Store and told him I was going to pull out of the gig that week. Don admonished me for letting him down, but also said he respected the fact that I was saving us both from embarrassment. We agreed that I’d call him again when I had a bit more experience under my belt.

And so I focused on playing the smaller clubs. I would use that stage time to get good, I decided, and then approach the more established venues.

The act was thin, but I would listen to the audience and take out stuff that didn’t work. And when all else failed, there was one thing that guaranteed a laugh . . . halfway through my set I would pretend to sneeze and then yank the wig off my head and use it as a tissue, before replacing it, all skew-whiff. Other times I would simply scratch my head, moving the wig in the process, and then continue talking without making any reference to it. I was eighteen years old and looked a lot younger – the audience was not expecting this to happen. They would half-gasp, half-roar. Sometimes they’d even applaud. At Churchill’s in Southend, one man in the crowd was drinking his beer when I moved the wig and was so shocked he bit straight into his pint glass. As he left the club for the hospital with blood streaming down his face, still laughing, he told the manager to get me offstage. He said I was a health hazard.

At one of my early gigs I moved the wig but didn’t get the laugh I was hoping for. One of the other acts pointed out afterwards that it was perhaps because I had walked in without the wig and put it on in view of some of the audience, while waiting at the bar. From that moment on, I always made sure to ‘wig up’ before I arrived at the venue. Often I would run into a neighbouring pub, into the toilet and ignore the raised eyebrows of the other occupants as I placed ‘Kimberly’ (David Williams had said I should give it a name) on my head.

On 8 November 1992, five weeks after that Punchlines show, I wigged up outside the Tube station, then arrived, as I now did every Sunday, at the White Horse to do a short set at the VD Clinic. You had to walk into the main room in the pub in order to get downstairs and, as usual, I arrived far too early, sat down and ordered my customary Diet Coke.

My jaw hit the floor when I saw, at the next table, my idol Bob Mortimer.

Was there a more brilliant, more vibrant, more original and just plain funnier act in British comedy in the early nineties than Reeves and Mortimer?

Let me answer that for you.

No.

In fact, no one came close.

Jim Moir, aka Vic Reeves, had been around for a while. I had seen him occasionally on Jonathan Ross’s TV programmes and he and Bob Mortimer had developed a bizarre spoof variety show called Vic Reeves Big Night Out, which had transferred from the Goldsmith’s Tavern to Channel 4, where it ran for two series on Friday nights.

As a teenager in Stanmore who wasn’t quite allowed out yet on a Friday night, I had watched the first episode with expectations that weren’t met. In fact, I was mystified. Reeves kept promising things that were going to come up later in the show that simply didn’t. And there were no celebrity guests. I couldn’t work it out at all. By the end of the episode I was so irritated that I pompously called up Channel 4 and told them that I didn’t get it.

I tuned in again the following week, but only because I was convinced that I was watching something historically bad, something that would almost certainly be removed from air before the series could run in its entirety. This time I recognised the return of some of the weird non-jokes from the week before, understood that none of the so-called celebrity guests would actually be appearing, that instead Vic and Bob and their pals would be playing everyone. By the end of the series I was not just a convert, I was a fully fledged apostle.

In the White Horse pub that November night in 1992, I rushed over to Bob Mortimer, who had left his small group of friends and was on his way to the toilet.

‘Hi Bob i am a huge fan i am also a comedian like you are you coming to the-show tonight?’

And it turned out he was. He said his friend Dorian was compèring.

Dorian Crook was (and still is) a man from another age. The late fifties, I would say. The clothes he wore, the car he drove – even the jokes he told – could have come straight out of a Terry Thomas film. By day he was an air traffic controller, by night he was an aspiring comedian. He had been at art school with Vic Reeves and subsequently had become embroiled in Vic and Bob’s antics, making brief appearances in their stage shows and joining them on tour. Now he was branching out on his own. His set – a parade of puns, one-liners and Christmas cracker-style jokes – was entirely original and of his own creation, but was so traditional in its tone and subject matter that it gave the impression of having been excavated from the distant past. Some audiences – hungry for something more biting and fashionable – resisted Dorian’s charms, but those audiences who had had their fill of knob gags and hectoring political invective, and who were willing to go along for the ride, laughed uproariously throughout. There was something joyous and liberating about watching Dorian. As with Vic and Bob, it was a bit like he wasn’t supposed to be there, like he had somehow wandered in and managed to get onstage. He was cheeky.

Downstairs the gig began. I lurked nervously at the back of the room, until it was my turn to perform. With the great Bob Mortimer in attendance, I decided to give it everything.

In the five weeks since my first ‘official’ gig at the Punchlines, I had added a dynamic new aspect to Sir Bernard’s persona. I’d been heckled a few times – often before the act had got going – and, terrified and without any decent put-downs, had started to respond by screaming back at hecklers in a rough Cockney accent . . .

‘I will cut your fucking face! Do you want some? DO YOU FUCKING WANT SOME?’

And then I would turn straight back into the elderly posh old man again, as if nothing had happened. The audience – initially startled – would burst into hysterics.

Eager to utilise anything that got a laugh, I had started to incorporate Chumley’s outbursts into the set, regardless of whether anyone was heckling or not. The anecdote would be routinely punctuated with these horrendous, incongruous streams of abuse, often aimed at anyone who was returning from the bar or simply just someone who happened to be sitting in the front row.

As I performed, I noticed Bob Mortimer making his way down to the front. I certainly didn’t scream at him. I idolised him. However, I did allow myself to glance in his direction once or twice and I saw that he was laughing heartily.

After the show I was in the pub upstairs, wondering if and how I could talk to Bob again. I needn’t have wondered. He came over to me and, making no reference to our brief interaction before the show (maybe he had forgotten – after all, I had been wearing the wig), he introduced himself.

‘Hello, my name’s Bob. I work at a production company called Channel X. I really enjoyed your act. I wondered if you have an agent or a phone number I can pass on?’

Did I fly home that night? I might well have done. I might have soared up into the sky, circled a star and then floated back down over London, towards the suburbs. Did I sleep a wink? Did I even need to? History had been made. I had not only met Bob Mortimer – JESUS CHRIST, I JUST MET BOB MORTIMER – but he had asked for my phone number.

I cannot emphasise enough what a pivotal moment this was for me – in my life, let alone my career. I adored Vic and Bob. To me they were gods. They were Lennon and McCartney. And I was to become their drummer.

Sorry, I couldn’t resist.

I still pinch myself.

It was to be a few months before I heard from Bob, but with the confidence that grew from this chance meeting, nothing was going to stop me. Storm or die, paid or unpaid, I got as many gigs in my diary as possible. I didn’t care what or where they were. I pushed and pushed myself, performing every night, twice a night if I could.

And . . . I got better. A lot better. And I decided it was time to call Don Ward again and get that open spot at the Comedy Store back in the diary.

The Comedy Store had played host to every great British alternative comic and you saw their photos lining the walls as you descended the stairs. Paul Merton (then Paul Martin), Jo Brand, Rik Mayall and Adrian Edmondson, French and Saunders, even Robin Williams had turned up on a few occasions to try stuff out.

I was never going to get a paid booking there, I was too new for that – so it was more a rite of passage. I just had to do a gig there, at least once.

I did it. And it actually didn’t go too badly.

I did shit myself that morning, though – literally – while serving a customer in the shop.

Ah yes, the shop.

I was leading a double life. By night I was a caped crusader, swooping down through the windows of comedy clubs, reducing audiences to hysterics – or goading them into abuse – before disappearing off into the night. And by day I sold pencil cases, rosettes, scarves, ashtrays – anything, as long as it was emblazoned with Chelsea FC.

Chelsea Sportsland, it was called – a name that never sounded anything other than ridiculous, and which irritated and alienated the largely working-class English fan-base, who still ate dodgy burgers and pissed in each other’s pockets at half-time. Chelsea Sportsland reflected the creeping Americanisation of British culture. Saturday nights on ITV were dominated by a new US format – Gladiators; rockers banged heads to the grisly nasal screeching of Axl Rose. London even had its own gridiron team – The Monarchs.

When Sky paid what was then an astronomical £304 million over five seasons for the rights to broadcast games from the brand new Premier League, they featured cheerleaders at half-time. Football fans were unimpressed, and Chelsea supporters were not too happy either about the vision that Chelsea Football Club and Clive Pollard had for a new football shopping experience. Alongside the Chelsea kits, footballs, posters and T-shirts were a load of baseball jackets.

‘What the fuck is this shit?’ asked one of the more articulate fans as he squinted at an obscenely priced and completely pointless Chelsea baseball shirt.

This was pre-Abramovich Chelsea. This was pre-Matthew Harding Chelsea, even. This was the Ken Bates era, when you stood on the Shed for a few quid, screamed at Nigel Spackman for missing a sitter and called Graeme Le Saux a poof because he read The Guardian.

Tony, the shop manager, was a Watford fan. Vince, who also worked there, supported Leeds, and I was, of course, a Gooner, but on a match day we’d all have to sport Chelsea tops – not the blue one, thank God, but their brand new third kit – white with vertical thin red stripes. Beneath it, in an act of defiance, I would wear my Arsenal top, but that would show through, so I’d have to wear a white T-shirt between the two layers. I was roasting!

Before and after the match, the shop would be mobbed. Despite supporting a rival team, I used to hope Chelsea would win purely because it would put the customers in a better mood.

The customers generally seemed to be made up of two different types. There was your rough’n’ready Chelsea diehard, who knew everything about the club and, not unreasonably, assumed I did too. I was often engaged in long, misty-eyed conversations about Peter Osgood and Bobby Tambling, during which I would bluff my way through, pretending I knew who the hell they were.

One of the techniques I employed was to use an all-purpose word of my own invention that would hopefully buy me time or, if I was particularly successful, end the discussion completely.

‘Oh yeah,’ I would say, ‘only one word for that: morditorial.’

Few people want to admit they don’t know what a word means, so I used to get away with that one frequently – and still do, sometimes. Feel free to use it yourself, by all means, though I would request that you don’t ascribe an actual meaning to it, because then it will simply be just like every other word.

#KeepMorditorialMeaningless.

The other type of customer we would play host to was your posh Kensington High Street-type chappie, clearly unfamiliar with the game but keen, as a local, to ‘get stuck in, you know’. I’d lay it on thick with these guys, insisting that real fans bought the whole kit, and the jumpers, T-shirts, cufflinks and ties. I found you could sell them anything.

There was also a third type of customer in the shop – well, just this one guy, really – who was very friendly and had a giant spider tattoo on his face and a large thick swastika on his forehead. He was so nice and funny that I decided he surely must have had the tattoos done when he was young and incredibly stupid. He was a different person now. One day a Motown song came on the radio and I started humming along.

‘We don’t sing that stuff, mate,’ he said. I changed the station.

I toiled in Chelsea Sportsland by day and toured the comedy clubs by night. On that morning in the winter of 1992, now a seasoned pro with a full two months of stand-up experience under my belt, I woke up in a cold sweat. I was calling my own bluff. I was actually going to play the Comedy Store.

As usual I grabbed two scalding strawberry Pop-Tarts (another recent American import) fresh from the toaster, wrapped them in silver foil, got in Vince’s freezing-cold clapped-out Citroën and gave him two shiny pound coins to pay for petrol. He drove us to the shop – which took the best part of an hour. On the way, as ever, we raged about the villainous Tory government – Major, Portillo, Lilley and Co. We shared the hope that one day Labour would displace them and knew that when they did Britain would run perfectly again.

Our manager Tony had gone to the toilet. I had been left in charge of the shop, as Vince hadn’t been working with us for very long. We had some customers in and I was climbing a shelf to bring down a selection of jumpers when I felt a fart brewing.

I had recently perfected – or so I thought – an ingenious method of concealing a blow-off in company. Not necessarily the scent of it – the severity of which was inevitably dependent on whatever mélange of backstreet junk food I had polished off the night before – but the sound of it.

It had occurred to me that if I could manufacture a strident enough cough to coincide with the expulsion of said gas, then those present would be none the wiser. Sure, they might pause at a later moment to enjoy the aroma of a nearby gardenia or peony and in the process inadvertently inhale and subsequently gag at the tang of Tuesday’s Birds Eye Potato Waffle by way of the large intestine, but – crucially – at the moment of auditory impact they would be none the wiser as to the creator of the offending pop.

With two more customers appearing in the shop, the opportunity to further develop my groundbreaking theory of fartivity came upon me and, as I had been prone to do, I exercised my fine powers of coordination with focus and determination.

Reader, I am proud to inform you that fart and cough were fused quite exquisitely. Certainly there was not even the slightest turn of head or wrinkle of nose from any of the assembled personages.

I am less pleased to tell you that, because I had ejected perhaps too enthusiastically, a voluminous quantity of merde shot out of my anus and into my underpants. Indeed, I fear a pellet or two may even have made its way down the trouser leg and onto the floor.

A butt-clenched stagger to the door followed, as I excused myself, leaving a helpless Vince stranded on the shop floor with several eager customers, confusion and betrayal in his eyes. Where was I going? How could I forsake him? Had I forgotten he didn’t know how to properly operate the till yet?

With Tony occupying our shop’s only lavatory (he was later to return in fury at my absence), I somehow managed to totter to the travel agents next door: another Chelsea franchise, where you could book a trip to watch the team play abroad, though it was many more years before they would actually qualify for a European tournament.

I smiled weakly and asked for the key.

Catching it nimbly, I headed inside. There was nothing I could do but commence the industrial-sized clean-up job. Of course, had there been any toilet paper in there it might have been a little easier. Suffice to say I had a relatively decent reception at the Comedy Store that night, and if you looked closely enough you would have been able to see that I wasn’t wearing any socks.