Читать книгу Somebody to Love - Matt Richards - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5

ОглавлениеAt around the time that the Bulsara family was fleeing Zanzibar for their new lives in London, HIV was beginning its own migration across the world.

For decades, ever since the initial jump of the virus from a chimpanzee to a human sometime around 1908, it had remained, by and large, contained within the Republic of Congo. The country had been granted independence from Belgium in June 1960 and then dispensed with the name of the Belgian Congo. In fact, the year in which Belgium ceded interest and governorship in the region has been identified as a crucial and pivotal mid-century moment of divergence in the spread of HIV globally.

It was the very ambition to develop the west of Africa by the great Western powers that, ultimately, created this situation and provided the routes for HIV to spread beyond the ‘Dark Continent’. The desire to plunder the Congo region for its ivory, rubber and diamonds, and the subsequent railway network created to service such intensive industrialisation, produced the perfect environment for the virus to spread. Kinshasa (formerly Leopoldville) rapidly became the best connected of all African cities and, as such, was the perfect conduit from which HIV could spread rapidly. By 1948 over a million people were passing through Kinshasa on the railways every year and this unwittingly enabled HIV-1 to be transmitted throughout the country. At some point between the end of the 1930s and the early 1950s, the virus had spread from its epicentre.

Signs of the virus reaching out were there for all to see, but no one would know what they were looking at, or what they were looking for. As early as the 1930s, Dr Leon Pales, a French military doctor, spent some time observing the soaring death rates among men constructing the Congo-Ocean railway. After conducting autopsies he found in 26 of the deceased workers a wasting condition he named Mayombe cachexia. This condition, named after the stretch of the jungle where the men had died, resulted in atrophied brains, swollen bowel lymph nodes and a number of other symptoms that would later become synonymous with HIV. But, during the 1930s, it was simply another unidentified tropical malais.

Therefore, HIV was able to spread extremely quickly across the Democratic Republic of Congo, a country the size of Western Europe, as a result of the railway network and, to a lesser extent, the waterways. The changing sexual habits of the country’s population, in particular the rise in the sex trade, also contributed greatly in enabling the virus to become a pandemic. The social changes surrounding independence in 1960 also contributed; a study by Dr Nuno Faria of Oxford University’s Department of Zoology states that this year ‘saw the virus “break out” from small groups of infected people to infect the wider population and eventually the world’.1

As well as medicine and the creation of infrastructure, there remained the most effective method of the virus being transmitted: sex. The sex trade in the Democratic Republic of Congo flourished as a consequence of the building of roads and railways and the increase in industry within the region. The construction workers, miners and administrators who flooded into the region to seek employment were predominantly male (they outnumbered women in the city of Kinshasa by two to one) and they sought out the prostitutes who, taking on a large number of clients and practising unsafe sex, were all unknowingly complicit in helping the virus take hold in the city. From here the virus would spread to neighbouring regions via the very roads and railways these construction workers were building. A study in the journal Science suggests that, because of the medical programmes and this increased sex trade, HIV spread from Kinshasa rapidly as infected individuals travelled along their newly constructed railways and roads and even the old waterways. By 1937, HIV had spread four miles from Kinshasa to the nearby city of Brazzaville; by 1946 it had reached Bwamanda, 583 miles away; and by 1953 it had reached Kisangani, over 720 miles from Kinshasa. The authors of the study claim that, by 1960, the spread of the virus had become exponential in West Africa, although no one realised it.2 How many Africans died of the disease can only be speculated – perhaps, over 80 years, as many as 200m?

Then, sometime in the mid-1960s, HIV crossed the Atlantic and landed in Haiti. The catalyst for this transmission of HIV was yet another goodwill gesture, one that backfired spectacularly. Once independence was granted to the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1960, most – if not all – of the Belgian officials made a hasty retreat from the region, leaving a critical vacuum at the heart of the newborn Republic.

To fill this void UNESCO shipped thousands of Haitian teachers and technocrats to Africa, specifically the Democratic Republic of Congo. A large proportion of these were based in Kinshasa. Ideal recruits to step into the shoes vacated by the Belgians, they were French-speaking, well-educated, black, and more than happy to desert Haiti and the brutal dictatorship of ‘Papa Doc’ François Duvalier. They spent weeks, months or years working in West Africa, in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola and Cameroon before returning to their homeland. It was when these professionals arrived back home, sometime around 1964, that the HIV-1 subtype reached Haiti.

This timescale corresponds precisely with the thousands of Haitians who went to Africa in 1960 to work and who returned during the mid- to late-1960s and early 1970s once Zaire (the Democratic Republic of Congo had renamed itself Zaire in 1971) had completed the training of local national managers. En masse, Haitians began to leave central Africa after 1968, although many had already returned home. In 1998, J.F. Molez wrote a paper for the American Journal of Tropical medicine which states: ‘Medical investigations made in Haiti from 1985 to 1988 and clinical observations reported the deaths of retired Haitian managers who had lived and worked in Zaire and then returned to Haiti (and had lived there for a period of 10–15 years) that were suspected to be due to AIDS’. Given the length of time from infection of HIV to death from AIDS in the 1980s was seven to ten years, these dates align perfectly with the theory that Haiti was suffering an AIDS epidemic of its own around 1970 following the return of its workers from Zaire during the late-1960s.

But it wasn’t just sexual intercourse in Haiti – be it heterosexual or homosexual – that led to the virus spreading there. Something else was happening in Haiti’s capital that exacerbated the problem, a problem no one knew existed at the time, of course. Dr Jacques Pepin claims another of the factors in the rapid expansion of HIV in Haiti was a plasma centre in Port-au-Prince. It only operated for two years, 1971 and 1972, but was known to have low hygiene standards. During those years, impoverished Haitians were being encouraged to sell their blood plasma to the US for derisory sums as America was in desperate need of plasma for transfusions, as well as for the protein elements it contains, such as gamma globulin to inoculate against hepatitis. The US was, apparently, unable to meet its own demand for plasma because there were not enough healthy donors willing to give blood. Part of the reason for this was that most Americans were affluent enough not to be attracted to donate blood whereas the poverty-stricken Haitians were more than willing to sign up for $3 per donation.

A company called Hemo-Caribbean negotiated a ten-year contract with the Haitian Government’s Minister of Interior, Luckner Cambronne, leader of the feared Tonton Macoutes secret police and nicknamed the ‘Vampire of the Caribbean’.3 Hemo-Caribbean used a relatively new procedure, which involved the donor giving a litre of blood, from which the amber plasma was harvested out, and then the blood pumped back into the person who donated it. All this for a payment of $3, which could be boosted to $5, if the donor was willing to have a tetanus vaccination, which made their plasma more valuable because additional tetanus shots could then be harvested from the plasma. After this, their own blood was pumped back into them, meaning they could then go back and donate again and again in quick succession without becoming anaemic.

There was a catastrophic problem with this, however, which was that the blood of countless donors was inadvertently mixed together in the plasmapheresis machine before being pumped back into them, thus infecting potentially every donor – and therefore recipient – with any blood-borne virus the donors might be carrying . . . such as HIV.

But Hemo-Caribbean seemed perfectly happy with the manner in which the plasma was collected. In an interview with the New York Times on 28th January 1972, Joseph B. Gorinstein said of his procedures, with a somewhat chilling nonchalance, that the plasma his company processed was ‘a hell of a lot cleaner than that which comes from the slums of some American cities’.

It wasn’t until later in 1972 that President Richard Nixon asked for an investigation into the blood business in the US, but by that point, with no screening for HIV because it wasn’t on anyone’s radar, the virus was already circulating around Haiti and, most probably, it had already entered the US either in the infected plasma or via a single infected immigrant who had arrived in a large city such as New York or, more likely, Miami only 700 miles away.

This single migration of HIV from Haiti to the US is called the ‘pandemic clade’ by investigators and represents a key turning point in the history of the AIDS pandemic. It is called a single migration only when it successfully establishes itself. Individuals with HIV may have crossed into the US and infected several people but the lineage of infection burnt out. The single successful event is estimated to have happened between 1969 and 1972. This would fit the subsequent epidemiology of HIV in the US, as the first cases of AIDS were reported roughly ten years after HIV is thought to have entered the country from Haiti, the precise interval between infection with HIV followed by progression to AIDS and subsequent death.4 Just as it had before in the Congo, in the decades before mass travel (and colonial medical programmes using a hollow-bore needle), the virus would remain lurking for almost ten years before anyone noticed it.

The death of a teenage boy in St Louis in 1969 of an unspecified illness baffled doctors at Washington University, and suggested to some that the AIDS virus might have already been in the US several times before the epidemic of the 1980s kicked off. The 15-year-old African-American named only as Robert R., but subsequently identified as Robert Rayford, presented himself to a clinic in 1968 suffering from an assortment of ailments including swollen lymph nodes, swelling of the legs, lower torso and genitalia. For 15 months he was treated in three different hospitals but became increasingly exhausted, lost a dramatic amount of weight, and suffered severe chlamydia. None of those treating him in any of the hospitals could diagnose his illness. Eventually he died of bronchial pneumonia and an autopsy found he had Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) lesions throughout the soft tissues of his body, a hallmark we later became aware of AIDS infection.

It wasn’t until 1986 that doctors were able to perform specific tests on tissue samples from Robert Rayford. Two tests were conducted: blot tests of his serum, a precise test for AIDS virus antibodies, and also a test for the P24 antigen, a virus protein that gives further evidence of infection. Both tests came back positive but, crucially, it wasn’t the strain that became known in the late 1970s and which spread AIDS worldwide. Doctors remained baffled. Rayford had never had a blood transfusion, didn’t do drugs, had never left the area and no other cases had been reported in his vicinity. The general conclusion was that there must have been several different strains of HIV at low level already making incursions into different countries, including the US, and at some point one of these strains became established and spread the pandemic. It is possible that, as in Africa, other people in the US did have HIV and died from it at a much earlier date but that no one had ever connected these deaths to AIDS because no one was looking for a virus they didn’t know existed.5

Most of the evidence points to the fact that, although various strains of HIV might have already been in existence in the US or, indeed, other parts of the world before the 1970s, the most likely route is that the deadly HIV-1 came to America from Haiti via one migration between 1969 and 1972 and established a foothold within the country then subsequently spread imperceptibly. In the ensuing years, the virus followed certain paths of chance and opportunity in certain subcategories of the American population.

‘The virus reached hemophiliacs through the blood supply. It reached drug addicts through shared needles. It reached gay men – reached deeply and devastatingly into their circles of love and acquaintance – by sexual transmission,’ suggested David Quammen.6

For a dozen years or so it travelled quietly from person to person. Symptoms were slow to arise; death lagged some distance behind. No one knew the cause, and no one associated the deaths.

At some point in the 1970s, someone would give the virus to a Canadian airline steward called Gaëtan Dugas. Then someone would pass it on to the Hollywood actor Rock Hudson.

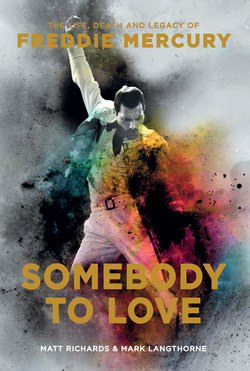

And just over a decade after it arrived from Haiti, someone else would give it to Freddie Mercury.