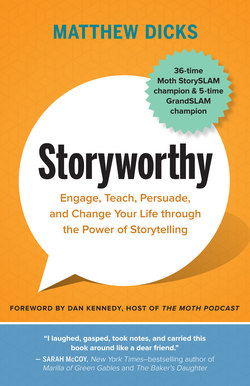

Читать книгу Storyworthy - Matthew Dicks - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

In early 2000, I got onstage, I told a story at this thing called The Moth, and something in my heart and head felt better. I remember talking about my biggest screwups, about some childhood dreams that hadn’t come to pass, and about how my attempts to pursue them at half-steam were clumsy and ill-fated. The story I told that night, about going to Austin to become a singer-songwriter and discovering the hard way that I wasn’t prepared or particularly good at songwriting, felt like the most deflating stuff any of us go through in personal defeats. Up to the moment I stepped onstage at The Moth that night, my life felt as if the stain of failure had been on me since about age twenty. But when I opened my mouth and shared a story about the details of that trip to Austin, the crowd laughed. Which made me smile through the bundle of nerves I was that night, and somehow made me feel like maybe, just maybe, everything would be okay in this life.

If I can recommend storytelling to you for any reason at all, it would be that storytelling helps you realize that the biggest, scariest, most painful or regretful things in your head get small and surmountable when you share them with two, or three, or twenty, or three thousand people. The other reason I can recommend storytelling, and learning about it with the book you’re holding, is that we’re all disappearing — you, me, everyone we know and love. A little heavy for a foreword maybe, but when you tell stories, you do yourself a kind favor by taking a moment to write your name in the wet cement of life before you head to whatever is next. This is a much more selfless act than conventional wisdom would have you believe. It’s a little like leaving a note in the logbook on the trail that others will be hiking after you, a note that might give the next hiker a clue: “Keep your eyes open for rattlesnakes by the bluff at the two-mile mark” or “There’s fresh water at the fire lookout if you’re running low” or “I live in the woods now, and I don’t care if I never see an iPhone again after staring at one for a decade until my head was tortured, my eyes were ruined, and my heart was broken.”

Telling stories about your life lets people know they’re not alone; and it lets some of the people closest to you — like family and loved ones — see your life apart from the context of family and without the kind of revisionist hindsight we can sometimes fall into concerning the ones we love most. Opening your mouth, getting out of your head, and your house, so you can be fully engaged in your life and the lives of others for the night — that’s what storytelling is all about, if you ask me. Or maybe it’s just as my friend Jesse Thorn joked: “Storytelling. In case you’re not familiar with it, it’s kind of like a less-funny stand-up comedy.” That line cracked me up — in some ways, it’s right on the money. Then weeks later, it oddly made me realize why I love storytelling so much: at its best, it’s not out to razzle-dazzle you at any cost. There’s no adversarial relationship with the audience; they’re not people leaning back in their chairs, drinking their two-drink minimum, signing an implicit contract that basically says “You better make me laugh.” There is no volley of anger like I’ve seen in comedy clubs; just a crowd of people who want to hear what you have to say and in some cases might be stepping up to the mic right after you to share something about themselves.

Sometimes it’s the funniest thing you’ve heard, and you’re rolling. Other times someone is getting attacked by a shark. Or going to space. Or sitting next to their crashed car and reevaluating their life. Or wondering how they got caught up in a world of white-collar crime. Or just dealing with an average Tuesday evening and trying to make sense of life like the rest of us on the planet. How can you not walk out of that room a changed person after feeling that connection?

In my early years of hosting The Moth StorySLAM, I never gave much thought to the numbers the judges in the audience hold up to score each storyteller. The scoring has always seemed in the spirit of fun, a device used to get the audience involved and to add some friendly stakes to the show. And early on, it never seemed to me that the storytellers were any more concerned with the scores than would be, say, a few friends throwing darts in a bar or playing poker for acorns on a camping trip. Even when we weren’t great onstage (and I’m also pointing the finger at myself here, as a host who sometimes tries to tell a story in the top or middle of the show), it was just part of the fun, because we were all there for each other, laughing or shrugging it off when a story went sideways on us. If nothing else, when I bombed something, I figured maybe I had been of service — hey, maybe someone in the audience who was too nervous to put their name in the hat and share a story heard me and thought, “What am I afraid of? I’m not going to do any worse than that guy!”

At some point as the years started racing past, I noticed storytellers caring about the scores; sometimes people would get angry if they didn’t get the score they thought they deserved. Storytelling was getting a lot of press at this point — The Moth Podcast was up to tens of millions of downloads a year, and tons of other great new storytelling shows were popping up around the country. And it was around this time that I started noticing a different kind of people coming around — a more competitive type of personality. I was vexed, frankly. It had always seemed like the most humble, fun-loving thing in the world to me. I mean, even the name of it never sounded cool: storytelling. How could you develop an ego or agenda to become internet- or podcast-famous (actual things, swear to god)? It’s a little like wanting to have the biggest house on the tiny-home scene.

It seemed like there was a phase when suddenly people who you could tell were seasoned actors or comedians were there; it felt like they were just there looking for a way to get another gig on their résumé, hanging around just long enough to see if this was going to be the thing that got them on TV somehow. Oh, no — the cool kids were coming around!

I felt I was developing a way of sussing out people who were the real deal and not just coming around for a hot minute to use storytelling as a stepping-stone. That had to be right about when I met Matthew Dicks. And here’s the twist: not only could you tell he was the real deal, the kind of person you wished was a family friend back home, but he somehow made me see that it was okay to want to work at getting better at this stuff. He’s the person I would watch whenever I was lucky enough to be hosting a show he was in. He taught me that trying to get better at storytelling also meant trying to get better at being a friend, or a son, a boyfriend, a brother, or just a better person. He’s a guy you can tell has been as heartbroken as you or me or anyone else carrying a heart around on earth, but he manages to set that aside, in the background and subtext of his stories.

It would be easy for a guy like Matthew Dicks to get onstage and tell an emotionally overwrought story to manipulate listeners into feeling something; oversharing and “emotion porn” are super-fast ways to get a reaction from an audience in the heat of the moment, and they wear off just as fast, leaving a mental hangover in their wake. But Matthew Dicks forgoes the aforementioned tricks and instead tells stories like the one about trying to impress his mom by jumping his BMX bike off the roof of his house growing up. And having it end miserably, but not without his sister nailing her cue of turning to their mother, as instructed by Matt, and exclaiming a then-popular TV show’s catchphrase: “That’s incredible!” This story is a perfect example of how Matt somehow gets you to feel bigger emotional stakes in subtext instead of hitting you over the head with them.

Matthew came along at a time when the New York storytelling scene needed someone to remind it that storytellers are, first and foremost, a family, no matter how large, no matter how many different shows exist, no matter in how many different cities or countries. The family might be millions of people all over the world at this point, but Matthew Dicks is the guy who makes you realize it was that big all along. That those of us performing on this so-called storytelling scene haven’t been doing anything new at all, just stepping up to a mic to partake in something that’s been happening since the dawn of time.

This book is the helping hand they didn’t have in the caves of Altamira. I mean, in fairness, they didn’t need it back then — they seemed to do just fine at telling stories. But the world has changed a bit over the past thirty-five thousand years, and the book you’re holding is a great resource. I’ve always said that a good storytelling show feels like a cross between therapy, rehab, and hanging out after dinner with friends. The idea of reading a book to get better at telling stories might seem a little academic, but you’re about to find out that this is a book written by someone with a great heart, who believes you’ve got a great life full of stories in you and ahead of you.

I have to admit I have a soft spot for the way Matt fell into storytelling — that he went to a Moth StorySLAM to make good on a promise, secretly hoping deep down that his name wouldn’t get called. And once he was in that room with everybody, he stuck around, but it’s almost as if he didn’t quite know what good could possibly come from it. Matthew Dicks hasn’t so much written a book about storytelling technique, or angling to get ahead in the smallest waters of the entertainment scene, or marshaling the will and ego to elbow your way past folks. He’s written a book about you and how it would be great to have you hanging out and telling stories with everyone. Even if you don’t quite know what good could possibly come from it.

— Dan Kennedy, host of The Moth Podcast