Читать книгу The Decadent Republic of Letters - Matthew Potolsky - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

___________

“Workers of the Final Hour”

Community is made of what retreats from it.

—Jean-Luc Nancy, The Inoperative Community

With surprisingly few exceptions, the history of the decadent movement has been told from the perspective of a single national tradition—with due acknowledgment of the French (most often), English, American, or German origin of this or that key figure or contributing intellectual thread. Written as part of a growing interest among scholars in cosmopolitanism, internationalism, and cross-Channel and transatlantic connections, The Decadent Republic of Letters regards decadence as fundamentally international in origin and orientation. The various names artists and critics have applied to fin-de-siècle literary movements tend to be identified with a single national tradition. Aestheticism was largely a British movement; Symbolism developed in France. Decadence, by contrast, was an international movement from the beginning, and had a lasting impact around the world well after the turn of the century. This book focuses chiefly on French and English writers of the second half of the nineteenth century, but the stylistic and thematic paradigms I tease out of the movement were adapted by writers from the United States, Latin America, Central Europe, and other regions.1 Defined by more than the familiar set of images, themes, and stylistic traits normally associated with the movement, decadence, as I present it here, is a characteristic mode of reception, a stance that writers take in relationship to their culture and to the cosmopolitan traditions that influence them.

This stance originates in a transatlantic encounter: Charles Baudelaire’s translations of and critical writings on Edgar Allan Poe. These texts provided later writers with a durable source of inspiration, but also, and more important, with a model of how to be influenced. Following Baudelaire, later decadent writers look enthusiastically to writers from other national traditions: Algernon Charles Swinburne wrote one of the earliest appreciations of Baudelaire in any language and was admired by advanced French poets; Paul Verlaine lived in England in the 1870s and was revered by the English decadents; Vernon Lee spent most of her life in Italy but wrote in English and published her works chiefly in England; Oscar Wilde composed Salomé in French and was regarded by French writers as a major theoretician of decadence; Friedrich Nietzsche imported his definition of decadence from Paul Bourget’s widely read 1881 essay on Baudelaire.2 The movement was disseminated through translations, imitations, and critical appreciations—all techniques designed to provide a new context for the foreign and unfamiliar.3 Essentially internationalist, decadent writing is a form of cultural production that begins with and recurrently thematizes the act of literary and artistic border crossing.

The radically syncretic and cosmopolitan texture of decadent writing accounts for the difficulty scholars have long had in defining the movement, or even fixing its major adherents. In his pioneering study of the fin de siècle, The Eighteen Nineties (1913), Holbrook Jackson identifies four characteristic elements of decadent writing: perversity, artificiality, egoism, and curiosity.4 Later scholars have added exoticism, morbidity, philosophical pessimism, and antifeminism, among other elements. None of these elements is exclusively decadent, however, in the way that the praise of nature is characteristic of Romanticism or the tracing of environmental influences on the individual is characteristic of Naturalism. Similarly, the major features of decadent style resemble forms of mannerism that extend into antiquity.5 The canon of decadent works and writers is equally unstable. Few of the writers I discuss in this book called themselves decadents. Wilde wrote canonically decadent books as well as society comedies; Baudelaire died before the decadent movement gained a clear identity, and was claimed by rival literary groups such as the Symbolists; Walter Pater resisted his association with the young decadents who championed his works; Michael Field abhorred the Yellow Book and its circle of contributors but read widely in the works of the French decadents. Noting the extreme difficulty of defining the term, Richard Gilman has suggested that decadence is nothing more than “the underside or logical complement of something else, coerced into taking its place in our vocabularies by the pressure of something that needs an opposite, an enemy.”6 He argues that the word should accordingly be expunged from the critical vocabulary. Yet the idea of decadence was central to the cultural politics of the nineteenth century, and dispensing with it, as Gilman advises, would distort our sense of the age. For artists, intellectuals, and the reading public in the period, decadence was a viable concept with real consequences. As a literary movement with a name and a manifesto, decadence dates to 1886, when Anatole Baju published the first issue of his flagship journal Le Décadent, but the term had already circulated for many years before in advanced literary and artistic circles, and underwrote a project that attracted writers from both sides of the English Channel who found common cause in each other’s works.7

Etymologically, decadence means to fall down or from (from the Latin de + cadere). It describes a temporal contrast or comparison. A body, a society, or an artistic form falls away from something prior and better: health, virtue, tradition, and so forth. Eighteenth-century historians such as the baron de Montesquieu and Edward Gibbon adapted this definition to explain the fall of the Roman Empire. In 1834, the French academic critic Désiré Nisard applied the term to literature in his influential study Études de moeurs et de critique sur les poëtes latins de la décadence, arguing that French Romanticism marks a decline of artistic value from the age of Louis XIV, much as the discredited corpus of “decadent” Silver Age Latin poetry marked a decline from the artistic and political unity of the early empire.8 Nisard’s study fixed the constellation of ideas and metaphors literary decadence still evokes today, from the imagery of Roman decline to sensual indulgence, extreme erudition, and linguistic complexity. Writers later in the century deployed the term both to praise and to condemn. Théophile Gautier, as we will see in Chapter 2, used the word to characterize the “maturity” of Baudelaire’s poetry, turning historical belatedness into an artistic virtue. Max Nordau, in his widely read 1892 book Entartung [Degeneration], took the organic metaphor underlying the concept literally, accusing fin-de-siècle writers of laboring under mental and physical debilities. Baudelaire, for his part, mocked critics like Nisard, ironically noting that if decadence is indeed an organic affliction, then poets like him have little choice but to accept their fate: “It is entirely unfair to blame us for accomplishing such a mysterious law.”9

The writers I discuss in this book use the word “decadence” and its familiar associations in a wide range of contexts and toward a variety of ends; more often than not, they regard it with Gautier’s and Baudelaire’s revisionary eye, transforming a term of opprobrium into a means of self-defense or countercultural identification. But I am less interested in tracing these uses in any systematic way than in documenting aspects of the decadent movement that remain obscure even for contemporary readers. Critics since Nisard have characterized decadent writing as if its qualities somehow followed from the definition of the term itself, as if there were certain essential traits that mark a text (or a person, or a historical moment) as decadent. But this reasoning is circular: decadent texts are decadent because they have decadent traits, which can only be discerned by analyzing texts one already assumes (or takes on faith) to be decadent. Not surprisingly, the word and the movement fall apart under scrutiny—as Gilman’s study demonstrates—or hang together in provisional or fundamentally unconvincing ways that must be defended with every new scholarly foray. This fact accounts for the prevailing “introductory” orientation of scholarship on the movement: every scholar of decadence becomes, as it were, a decadent scholar, seeking some fixed point amidst a kaleidoscopic array of names, texts, traits, rival movements, and stylistic gestures.10

I argue in this book, by contrast, that decadence is a consciously adopted and freely adapted literary stance, a characteristic mode of reception, rather than a discernible quality of things or people. It is a form of judgment and a way of doing things with texts. As Richard Le Gallienne perceptively put it in an article from 1892, decadence lies not in a particular theme or style but in “the character of the treatment.”11 Decadent writers sort incessantly through the materials of the cultural past, defining their relationship to others in the movement by collecting disparate themes, tropes, and stylistic manners from around the globe and binding them together according to their peculiar tastes and proclivities. Foregrounding acts of selection, juxtaposition, and critical discernment, they piece together ostentatiously borrowed parts, rather than purporting to create in any traditional sense or according to a clearly delineated doctrine. Reception is for these writers a crucial means of production.

Because it never adumbrated a single, unified doctrine, decadence attracted writers of strikingly various interests and talents, many of whom took up the stance for a time and later moved on to other forms, and even repudiated the movement altogether. The relationship of decadent writers to each another is closer to what Ludwig Wittgenstein calls a “family resemblance,” which is marked by “a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing,” than to the overriding unity of purpose that characterizes (at least ideally) a traditional literary group.12 They are united by the things they like and the ways they talk about them. The decadents incessantly drew lines of affiliation back in time and across national borders, declaring their (permanent or provisional) allegiance to the movement by asserting a family resemblance with admired contemporaries or figures from the past. These lines shifted often, even for the same writer at different moments in his or her career. Baudelaire and Poe are constant points of reference; for others, influences as diverse as Pericles, Petronius, Apuleius, Ronsard, Nicolas Chorier, Sade, Blake, Flaubert, Verlaine, and Wagner supplement or even supplant their role. Works are “decadent” not because they realize a doctrine or make use of certain styles and themes but because they move within a recognizable network of canonical books, pervasive influences, recycled stories, erudite commentaries, and shared tastes. Each decadent text borrows from and expands the network, locating itself by reference to the names or books it evokes and leaving its own contributions behind.13

Regarding decadence as an evolving literary stance rather than a fixed set of traits brings into focus a mostly unrecognized vision of cosmopolitan community that pervades the movement. Critics have long argued that the key characteristic of decadent writing is a turn away from the world and the public interest to the interiority of the private self. True to the etymology of the term, decadence deviates from or rejects some norm. It is nihilistic, condemnatory, and destructive, a perverse mirror of the bourgeois individualism it claims to abhor. In his essay on Baudelaire, Bourget describes decadent societies as organisms in which the “cells” no longer work together in the interest of the whole; such societies “produce too few individuals suited to the labors of communal life.” Decadent style exemplifies this social atomization: “A style of decadence is one in which the unity of the book is decomposed to make way for the independence of the page, the page is decomposed to make way for the independence of the sentence, and the sentence makes way for the independence of the word.”14 Nordau sees the decadent as a willful deviant, “an ordinary man with a minus sign,” suffering from a “mania for contradiction,” which only masks his fundamental conformism: “The ordinary man always seeks to think, to feel, and to do exactly the same as the multitude; the decadent seeks to do exactly the contrary.”15 More recently, George C. Schoolfield characterizes the decadent as a besieged elitist, who “regards himself as being set apart, more fragile, more learned, more perverse, and certainly more sensitive than his contemporaries.”16 Other recent critics have treated decadence more positively as a form of cultural critique, but they effectively define the movement in the same terms as Bourget and Nordau do. Charles Bernheimer writes, for example, that decadence entails both an appeal to and a subversion of accepted norms; it is “inhabited by a doubleness that puts fundamental moral and social values in question.”17 Most famously exemplified by Wilde’s epigrammatic deconstructions of received wisdom, decadent opposition here becomes strategic, an overturning of bourgeois ideology through parody, paradox, and subversive appropriation. The decadent, however, is still a nihilistic outsider who rejects social belonging out of disgust with the bourgeoisie.

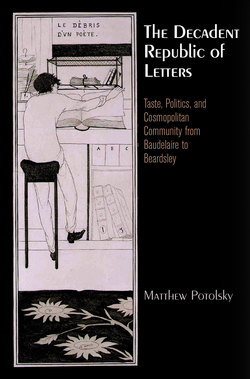

I argue in this book that decadent writing, so long associated with isolation, withdrawal, and nihilistic repudiation, is in fact preoccupied with communities. The fin-de-siècle literary and intellectual world was a ferment of burgeoning countercultures. Avant-garde writers rubbed shoulders and shared the pages of journals with anarchists, socialists, utopians, Uranians, feminists, spiritualists, and radical vegetarians. Although they did not always agree with the goals of all of these activists, the decadents regarded themselves as a part of the broader counterculture, and participated in its efforts to imagine new forms of affiliation and sociality.18 Decadent withdrawal is always collective, a ritualized performance of what Regenia Gagnier calls “creative repudiation.”19 Ostentatiously breaking ties with modernity and its dominant publics, the decadents do not isolate themselves but construct a new and more amenable imagined community, to borrow Benedict Anderson’s term, composed of like-minded readers and writers scattered around the world and united by the production, circulation, and reception of art and literature.20 The decadents produced a remarkable number of collective manifestos and literary journals, but their interest in community is most powerfully evident in the themes and subjects of decadent writing, which look decisively beyond the frame of any localized national coterie to new and radically international frameworks for sociocultural belonging. Decadent writers were fascinated with the creation and destruction of communities. They were drawn to martyrs, who die publicly for a persecuted group, and drew stories and political concepts from moments of historical transition (late antiquity, the end of the Middle Ages, the eighteenth century) marked by underground movements, revolutionary collectives, and secret societies. Decadent texts describe a striking range of quasi-utopian communities and promote new ideas about affiliation in the ways they address their readers. Significantly overlapping with the emerging gay and lesbian countercultures, decadence also provided a medium for writers to define communities united by sexual dissidence and nonnormative desires. The imagined community of other decadents provides writers from Baudelaire to Aubrey Beardsley with a coherent position from which to criticize contemporary political arrangements and to define the possibility of new ones.

Take, for example, an undated list of titles Baudelaire put together for a prospective monthly literary review. This list may have been written as early as 1852, when he drafted a proposal for a journal called Le Hibou philosophe [The Philosopher Owl], or as late as 1861, when the future decadent Catulle Mendès was launching his own journal, the Revue fantaisiste, and frequently sought Baudelaire’s advice. A number of titles on the list evoke stereotypically decadent images of isolation and retreat from the world: “L’Oasis,” “L’Hermitage,” “La Citerne du Désert [The Cistern of the Desert],” La Thébaïde, “Le Dernier Asyle de Muses [The Last Refuge of the Muses].” Another group of titles, however, describes communities or principles of affiliation: “Le Recueil de ces Messieurs [The Collection of These Gentlemen],” Les Bien Informés [The Well-Informed], Les Hermites volontaires [The Willing Hermits], Les Incroyables [The Incredible Ones]. Another title, Les Ouvriers de la dernière heure [Workers of the Final Hour], alludes to a parable of Jesus (Matthew 20:1–16)—better known in English as the parable of the workers in the vineyard— that concerns the mysterious nature of election (OC I, 53). Yet another, which Mendès adopted in 1875 for his most successful literary review, makes the underlying communal spirit of Baudelaire’s list manifest: “La République des Lettres.”21 The Enlightenment Republic of Letters was a loosely organized international group of writers and intellectuals who defined themselves as a polity apart, devoted to finding alternative models of affiliation and political order. Although the “citizens” of this republic lived under the rule of monarchs, they enacted the classical republican ideal of civic humanism and political participation on the page rather than within the borders of the kingdom.22 Working under the modern absolutism of the French Second Empire, Baudelaire resurrects this ideal in his list of titles, imagining a similarly international community of sympathizers brought together by writing and by a collective sense of alienation.

The communal ideals pervading Baudelaire’s list suggest that the overwhelming critical focus on decadence as decline, deviation, parody, and subversion distorts the most significant aims of the movement. This is true of the themes and stories to which decadent writers are drawn and the styles in which they tell them. Careful study of decadent texts reveals their ingenious reversals of social and artistic norms, but it is difficult for even a casual reader to miss the role of encomium, tribute, and eulogy in decadent writing. Decadent characters lavish praise on their favorite books and paintings, swoon over purple passages from decadent classics, launch panegyrics for ideas despised by the bourgeoisie, contemplate with great admiration the perversities of Nero and Caligula, or punctiliously follow the lessons of their decadent masters. Baudelaire composes long and fulsome dedications to his works, defends abused or misunderstood artistic figures, eulogizes the lost Paris of his memory, and lauds the use of cosmetics or the musical strains of flies surrounding a rotting corpse. Conversely, but within the same discursive register, he vituperates popular artists and writes venomous sonnets to his lovers. Wilde’s Salomé is composed almost entirely of expressions of appreciation or condemnation. The play opens with the Young Syrian’s praise of Salomé’s beauty, while Salomé herself addresses John with elaborate and starkly alternating words of praise and blame.

The rhetorical term for this mode of discourse is epideictic. Most critical writing is broadly epideictic, but decadent writers make the extremes of praise and blame central to both their critical and their poetic techniques. These techniques are not just a matter of individual temperament but a deliberate rhetorical choice, a way in which decadent writers appeal to an imagined community of sympathetic readers and writers by foregrounding the act of reception. The enthusiasm for the bizarre or recherché so often expressed in decadent texts carries a submerged communal element, embodying, as Kant noted about all judgments of taste, the liking of the perceiving subject along with an imperative for others to assent to the judgment. Just as Baudelaire admires Poe and Wagner for their insight into the failings of modernity or the transformative powers of art, so later decadent writers discover in the figures they praise (above all Baudelaire) a subversive, utopian, or nostalgic alternative to the present order. The reading of decadence as oppositional casts the decadent writer as a bitter outsider, condemning mass society in the name of a wounded individualism; the epideictic mode, by contrast, inscribes the decadent in a community of interest.23 The decadents were arguably the first literary group to realize the now-familiar, even banal association of subcultural affiliation with taste—the sense of attachment felt not by virtue of national origin or religious affiliation but through a liking for certain cultural forms. Expressions of enthusiasm, sympathy, and intellectual friendship are the coin of the realm in the decadent republic of letters.

Recent theorists of community have sought to think beyond existing political practices by looking toward what Giorgio Agamben calls the “coming community.” Against communal bonds defined by blood, territory, language, and the opposition of friend and enemy that Carl Schmitt placed at the heart of political association, this sense of community registers the bare experience of belonging or being-in-common. Rather than comprising an essential identity, totalizing communion, or stable distinction between insider and outsider, it is a bond, as Jean-Luc Nancy writes, “that forms ties without attachments, or even less fusion … that unbinds by binding, that reunites through the infinite exposition of an irreducible finitude.”24 In their effort to imagine a community founded on admiration and the exchange of texts, the decadents anticipate this project. They describe community as a dispersed phenomenon arising out of discrete moments of artistic production and reception, an almost utopian sense of belonging forged across space and time. It is not a completed “work” but a series of encounters and sensations. To play on Walter Benjamin’s well-known formulation, rather than aestheticizing politics, they find special political significance in the practices of reading and writing.25

Modern communitarian theory is closely associated with left and liberal intellectuals, but over the course of the nineteenth century a range of political groups laid claim to the language of community, from utopian socialists writing in the wake of the French Revolution—whose theories of association would influence Baudelaire—to far-right nationalists and traditionalists.26 Against the impersonal networks, state institutions, and mass movements of what Ferdinand Tönnies called the modern Gesellschaft (society), socialists and traditionalists alike sought to define a more intimate, if always vanishing or incipient, Gemeinschaft (community).27 Some decadent writers were drawn to utopian socialism, while others looked to anarchism, and still others cast their lot with reactionary Catholicism or (later in their careers) fascism.28 Regardless of the politics of their authors, however, the communities I find in decadent texts are radically open and aleatory, almost to the point of nonexistence, their members bound only by a shared sense of participation in a decadent republic of letters. Decadent communities embody what Ernst Bloch has described as the “anticipatory illumination”—an imaginary insight into real possibilities for social and political transformation gleaned from fictional worlds.29 Pushing the notion of community to a conceptual breaking point, the decadents produce a vision of affiliation no longer in thrall to nineteenth-century paradigms like the nation or the “people.” The centrality of this vision to the movement has largely been lost to posterity, but for the decadents it was an ever-present possibility. The sense of community, they recognized, could begin with the opening of a book, and end when the book is put aside.

Recent scholarship on British aestheticism has persuasively teased out the underlying cultural politics of a movement that was long associated with the same apolitical turn from the world that still defines decadence. Aestheticist literary form served as a medium for marginalized groups—gay men and lesbians, middle-class women, socialists, and avant-garde artists alike—to criticize mainstream society and speak to others who shared their experiences and desires.30 Despite the fact that the lines between the two movements were exceedingly blurry, scholarship on decadence remains tied to the sense of isolation, social fragmentation, and nihilistic withdrawal that we find in Bourget and other contemporary commentators. I demonstrate in this book, however, that decadent writers engaged the most pressing issues of nineteenth-century political and social theory—law and the public good, constitutions and social contracts, nationalism, imperialism, and cosmopolitanism—from a wide range of political stances on the left and the right. More directly oppositional and more resolutely cosmopolitan than the aesthetes in their critique of contemporary communities, the decadents foreshadow the new kind of intellectual that Julia Kristeva names the “dissident,” a figure who challenges the master discourses of society not from the position of the sovereign individual doing battle with the masses but as an advocate of a transformatively “modern community.”31

The decadents adumbrate their ideal of a modern community against the twin pillars of the nineteenth-century bourgeois ascendancy: liberalism and nationalism. The most significant revisionary scholarship on the fin de siècle has for the most part focused on cultural politics, detailing the ways in which writers in the period challenged contemporary norms of gender, sexuality, and economic value. This approach has provided a much more nuanced picture of the historical moment than earlier scholarship had allowed, but it has also tended to overlook the important ways in which these writers also commented upon larger macropolitical issues. One notable exception is the work of scholars such as Linda Dowling and David Wayne Thomas, who have found suggestive traces of the liberal tradition in fin-de-siècle writing, from the language of autonomy and self-cultivation, to the individualization of aesthetic experience, to the hope William Morris and others pinned on the politically transformative powers of artistic appreciation.32 But the decadents’ engagement with liberal and other political theories is considerably more thoroughgoing, and often more critical, than Dowling and Thomas indicate. Even those decadent writers most clearly influenced by certain strains of liberalism (such as Pater and Lee, who are often grouped with the aesthetes) are also deeply suspicious of the kind of community liberalism imagines in theory and brings about in practice. Their disdain for nationalism arises from similar concerns. The decadents object in particular to the way liberal thinking and nationalist thinking sweep together entire populations under overarching rubrics, ascribing rights and privileges—those enumerated in constitutions or evoked by the mythology of a national character—to subjects who did not choose or never desired to be so defined. The self-selected community of taste so often imagined in decadent writing is a frankly elitist protest against and revisionary alternative to this quasi-universalizing contemporary order. It is a cliché of scholarship on the movement that the decadents harshly condemned the bourgeoisie; I show in this book that their attack had reasoned and politically sophisticated (if often troubling) foundations.

As Jacques Rancière has argued, art and literature are political not because they convey deliberate political messages or give form to the unconscious ideological positions of their producers but because they “change the cartography of the perceptible, the thinkable and the feasible.” Aesthetic forms enable the politically marginalized—those officially excluded from political participation or alienated from the prevailing social order—to discover a collective voice.33 Decadent writers find this voice in older ideas of social and political organization and in the possibilities for association opened up by the rapid growth of print culture in the period. Turning the tables on contemporary critics who accused them of excessive individualism, for example, Baudelaire, Swinburne, and Gautier, I show in Chapters 1 and 2, challenge the liberal valorization of individual self-interest by evoking the classical republican tradition of civic humanism. Disdainful of the rising tide of nationalism that dominated European politics after 1870, later writers like Joris-Karl Huysmans, Pater, Wilde, and Lee, I demonstrate in Chapters 3 and 4, counter the prevailing notion of a community united by ties of blood, a vernacular language, and geographical boundaries by advocating self-selected and international communities of taste modeled on the early modern libertine underground. Republican virtue and libertine subversion may seem radically opposed, but they both exemplify alternative models of community that make sense of the decadents’ disidentification with bourgeois modernity, providing them with a shared idiom for the critique of contemporary liberalism and nationalism. In Chapter 5, I look at the ways Lee, Pater, and Beardsley describe quasi-utopian communities composed of dispersed individuals who gain (or retrospectively embody) a sense of unity in and through acts of reading and writing but who may never meet face to face.

The theory of decadence, I noted above, arose out of the historiography of ancient empires, and long served as a commentary on the fate of modern nations, so it is easy to see how it could become a medium for critique as well.34 This critique was not lost on all contemporary commentators. Nordau characterized the decadents in Degeneration as part of a broader cultural threat to modern civilization, a threat epitomized for him by the tendency of writers in the movement to form alternative communities—specifically, artistic schools—that loudly rejected mainstream values. Yet Nordau is too easy to caricature, and with the exception of some perceptive discussions of the phenomenon in Pater’s writings, the fascination of decadent writers with politics and communities has remained obscure to later readers.35

The most obvious reason is the looming figure of Huysmans’s paradigmatic decadent protagonist the duc Floressas des Esseintes, from À rebours (1884), the novel that all but wrote what Eugenio Donato calls “the script of decadence.”36 Sick of the world, Des Esseintes escapes to an artificial paradise devoid of people (apart from his servants) but filled with objects, apparently substituting the passive thrills of perverse consumption for life in the real world. Des Esseintes’s dramatic withdrawal defined the decadent movement in the nineteenth century, and in many ways continues to define it for contemporary scholars. In an influential account of fin-de-siècle literary movements, for example, Gagnier cites Des Esseintes as the epitome of a decadent individual “psychologically incapable of living with freedom,” who seeks “immunization against contamination and an illusory autonomy” in the hierarchical and overtly structured world of art. By contrast with the sexually and politically radical aestheticism of Wilde and Morris, decadence is an escape from complexity and change, “a tiny, safe space” from which the writer can criticize bourgeois society without the cost of genuine political struggle.37 Gagnier’s taxonomy was instrumental in making aestheticism a significant object of investigation for Anglo-American scholars, but it also contributed to the relative neglect of decadence, which remains for most readers a shadowy and reactionary “phase” of aestheticism, a pale imitation of French forerunners, or a literary-historical wrong turn rather than an analytical category of its own. Fin-de-siècle writers did not always draw such clear lines. For example, scholars at the forefront of the recent renaissance in the study of Michael Field (the collective pen name of Katharine Bradley and her niece and lover, Edith Cooper) have situated the poets firmly in the milieu of aestheticism, even stressing their thoroughgoing opposition to decadence.38 Yet Michael Field maintained friendships with many of the leading figures of the decadent movement, and eagerly read the works of Baudelaire, Swinburne, Verlaine, and other prominent decadent writers. As I show in Chapter 3, Michael Field’s collection of ekphrastic poems Sight and Song (1892) establishes a lively dialogue with Swinburne and Verlaine, borrowing recognizably decadent strategies to carve out a specifically female and homoerotic space within the movement.

For Gagnier and other scholars, the deepest problems of decadence are political, stemming in particular from the association of the movement with reactionary thinking. The political views of decadent writers can be exceedingly cryptic, but as I have noted, they are not exclusively reactionary, ranging from the anarchist left to the monarchial right, often in the works of a single author. The classic instance is Baudelaire, who swung violently from an early interest in utopian socialism to reactionary conservatism in his later years. Other writers’ political views are similarly problematic. Swinburne cast himself as a defender of classical republican traditions and later became a jingoistic panegyrist of the empire; Huysmans began his career as a socially critical Naturalist, and later became an apologist for an ultraconservative strain of Catholicism; Wilde promoted socialism but also evoked the traditions of the British aristocracy; the French decadent Octave Mirbeau turned from an early conservatism to a later advocacy of anarchism; Gabriele D’Annunzio and Maurice Barrès were drawn to fascism in the twentieth century; Stéphane Mallarmé avoided identifying with any political party. This dizzying array of political convictions might be taken as evidence of ideological incoherence—a political style matching Bourget’s description of decadent literary style—but the decadents found common cause across party lines, seeing themselves as part of a larger movement despite their varying beliefs. As Richard Dellamora his written, “Decadent critique can be directed from liberal, socialist, and/or anarchist perspectives, as well as from conservative or even reactionary ones. Whether from the left or the right, however, decadence is always radical in its opposition to the organization of modern urban, industrial, and commercial society.” 39 The seeming chaos of decadent politics epitomizes the underlying interest in the fate of contemporary communities that writers in the movement shared with mainstream figures such as Bourget or George Eliot, as well as with fin-de-siècle sociologists such as Tönnies and Emile Durkheim. Whatever their explicit political lineage, decadent ideas about community are critical of contemporary society in ways that go beyond traditionalist appeals to blood and land. Indeed, decadent antinationalism takes aim at just this kind of appeal.

Since the eighteenth century, taste has been understood as a kind of embryonic politics. In Friedrich von Schiller’s succinct formulation, “If man is ever to solve that problem of politics in practice he will have to approach it through the problem of the aesthetic, because it is only through Beauty that man makes his way to Freedom.”40 The feeling for beauty is common to all humans, Schiller argues, transcending partisan interest and political circumstances to unite people sympathetically before they unite politically. Individual acts of judgment connect the subject to a larger community. A number of scholars, informed by Antonio Gramsci’s notion of hegemony, have noted that the nineteenth-century state achieved by political means what Schiller imagined in theory.41 The decadents make the politics of taste more explicitly partisan, and more directly critical of the hegemonic aims of the modern state, by investing their appreciative discussions of books, artworks, objects, and other writers with political imagery and ideas. Associating their outsider views about representation with a radical critique of modern social and political formations, they cast Poe as an avatar of republican virtue and treat the contracts formed between decadent teachers and students as parodic versions of the social contract. Baudelaire turns the praise of beauty into an attack on the division of public virtue from private pleasure that follows the establishment of bourgeois hegemony after the Revolutions of 1848. Decadent collections promote an idiosyncratic and cosmopolitan counter to the feverish scholarly activity that consolidated national literary canons in the period. Judgments of taste in these examples are an active site for political commentary, a means by which writers think their way into new forms of community. If decadence seems explicitly to turn away from the public and institutional structures of “politics”—to borrow Chantal Mouffe’s useful distinction—it implicitly addresses the dimension of “the political,” engaging both thematically and stylistically in the conflicts that underlie all social relationships, and that unite or divide communities.42 Decadence is at once a medium for political thought, a vocabulary for criticizing the foundations of liberalism and nationalism, and a method for imagining a community of the future. It would be wrong simply to dismiss the less savory aspects of the movement—its pervasive misogyny, orientalism, and antidemocratic elitism—but it is also wrong to let these attitudes entirely define our sense of the politics of decadence.

The Decadent Republic of Letters traces the emergence and development of a decadent discourse about community and politics from Baudelaire’s early writings to Beardsley’s unfinished novel The Story of Venus and Tannhäuser. As we will see in the first two chapters of the book, Baudelaire set the stage for the decadent movement by charging his discussions of artists, writers, and social types like the dandy with the language and conceptual categories of classical republican theory. In Chapter 1, “ ‘Partisans Inconnus’: Aesthetic Community and the Public Good in Baudelaire,” I find echoes of this theory in a wide range of Baudelaire’s writings. Although he is deeply ambivalent about contemporary republicans, Baudelaire draws upon the language and imagery of the classical republican tradition to comment on the relationship between art and community. Against the individualism and legal formalism of the ascendant bourgeoisie, he defines the production and reception of art and literature as collective acts. Beauty is not an escapist diversion from reality but a public good essential to the workings of the polis, the true res publica of modernity. I follow this idea as it emerges in Baudelaire’s discussion of artistic schools in the Salon de 1846, recurs in his descriptions of quasi-aristocratic “families” of elite readers, viewers, and social performers, and is transformed in the writings on Poe. Informed by the counterrevolutionary writings of the political theorist Joseph de Maistre, Baudelaire characterizes Poe as a martyr who sacrifices himself to a tyrannous American public opinion for the benefit of a sympathetic community devoted to the production and reception of beauty.

In Chapter 2, “The Politics of Appreciation: Gautier and Swinburne on Baudelaire,” I turn to Baudelaire’s earliest advocates in France and England, who characterize the poet in much the same way Baudelaire had characterized Poe: as a martyr for art and the foundation for a new community of taste. Reading key works of tribute published in the immediate wake of Baudelaire’s death—Gautier’s “Notice” to Les Fleurs du mal and Swinburne’s elegy “Ave atque Vale,” both from 1868—I trace out the ways in which the two writers both preserve and transform the poet’s ideas about community into what I call a “politics of appreciation.” Like Baudelaire, Gautier and Swinburne appeal to the imagery of classical republicanism. Borrowing the form of the Athenian funeral oration, Gautier characterizes Baudelaire as a warrior for beauty and the leader of an emerging countercultural community. He is a keen observer and recorder of modern decadence, who documents the corruption of the Second Empire and defends the rights of outsiders to form their own communities. Swinburne gestures toward the collectivist mythology of the republican city-state. His critical writings, which were deeply influenced by Baudelaire, make the appreciation of neglected figures a crucial responsibility of posterity; the critic posthumously provides the rebellious genius with the kind of sympathetic community he or she was denied while alive. In “Ave atque Vale,” Swinburne appeals to the republican trope of political fraternity to describe his sense of sympathy with Baudelaire, a sympathy founded not on personal interaction (the two writers never met) but on the production and reception of poetry. Gautier and Swinburne profess political beliefs starkly different from Baudelaire’s (and from each other’s), but together they canonize his claim that beauty is a contribution of the public good, and that reading and writing are collective acts analogous to political participation.

Chapters 3 and 4 unearth a long unrecognized decadent critique of nationalism. Decadent writers are highly cosmopolitan in their literary and artistic tastes and correspondingly disdainful of the violent nationalisms that informed European politics after the consolidation of the German Reich in 1871 and the rapid imperial expansion by the major powers in the following decades. Turning from the example of the republican city-state—an ideal increasingly adopted by nationalist writers—the later decadents associate themselves with another important influence in the formation of the movement: the early modern tradition of libertinism. Closely tied since the seventeenth century to antimonarchial and anticlerical sentiments, libertinism becomes a medium for decadent antinationalism. Although their works are not often pornographic, the decadents fashion themselves as modern libertines, an underground and transnational movement united around their peculiar tastes (artistic as well as sexual) and self-consciously subversive of mainstream norms and beliefs. The example of libertine subversion differs markedly from the early ideal of civic humanism and responds to a different political order, but it, too, is based on a vision of community and affiliation fundamentally at odds both with the modern Gesellschaft and with conservative nostalgia for a lost Gemeinschaft.

In Chapter 3, “Golden Books: Pater, Huysmans, and Decadent Canonization,” I trace the emergence of this subversive ideal by looking at the pervasive image of decadent collections and the interest among decadent writers in the process of canon formation. Decadent collections self-consciously look back to the libertine association of outsider taste with social and political subversion, an association materialized in the so-called gallant library of pornographic classics described in many libertine works. Like the gallant library, the decadent collection is filled with subversive books and objects, constituting a canonical expression of the decadent sensibility. Decadent collections take aim at the contemporary fashion for defining national literary canons. International, idiosyncratic, and manifestly artificial, these collections stand as an affront to purportedly organic national traditions in their design and their preoccupations. Looking at two works crucial to the formation of decadent taste—Pater’s The Renaissance and Huysmans’s À rebours —I show how collecting and canon formation are closely associated with images of national disintegration: porous borders, hybrid languages, and radical cosmopolitanism. This counternationalist model of canon formation informs the practice of what I call “mimetic canonization,” by which later decadents “find” themselves in the tastes of an influential mentor, much as the nation finds itself reflected in a list of national classics. The practice is suggestively employed in the infamous chapter 11 of Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, which details Dorian’s collections and tells of his descent into decadence, and in Michael Field’s book of ekphrasitc poems Sight and Song.

In Chapter 4, “A Mirror for Teachers: Decadent Pedagogy and Public Education,” I turn to another decadent appropriation of the libertine tradition. Both the decadents and the libertines are fascinated with the process of education. Libertine works are organized around scenes of sexual instruction and initiation that subvert social norms; the decadents similarly make education a central trope in their subversive attack on the form of the nation. I argue that the many stories of conversion, influence, and persuasion in decadence are directed against the specter of public education, which was a recent innovation in Europe and England. From its earliest emergence in the writings of early nineteenth-century German reformers, the idea of public education was closely associated with national formation. Schools shape the populace, transforming it from a collection of inward-turning small groups into a unified collective willing to defend the nation-state. Driven by vanity, desire, and a taste for domination or submission, decadent teachers and students become case studies in the folly of making education a means to or model for political order. I look at five decadent educational narratives that scrutinize the motivations of teachers and students in this way. Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s Venus in Furs, Rachilde’s Monsieur Vénus, and Lee’s Miss Brown all show teachers and students agreeing to pedagogical contracts that mock the liberal theory of the social contract. Rather than forming free and rational individuals, these contracts enshrine the students as paradoxically willing slaves. Turning next to Pater’s Marius the Epicurean and again to Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, I consider the discourse of influence that is so prevalent in decadent writing. Libertine works assume the ability of teachers to shape their students at will; for Pater and Wilde, by contrast, education ideally takes the form of an aesthetic self-culture that may be stimulated, but never fully directed, from above. Marius the Epicurean and The Picture of Dorian Gray describe the problematic lure of influence for both teacher and students, associating the desire for domination and submission their characters express with the alliance of public education and state power.

Gathering together a number of conceptual threads pertaining to international and aesthetic affiliation that run through the book, Chapter 5, “A Republic of (Nothing but) Letters: Some Versions of Decadent Community,” looks at three decadent works about the Renaissance—Lee’s Euphorion, Pater’s Gaston de Latour, and Beardsley’s The Story of Venus and Tannhäuser —that describe communities formed by reading and writing. Baudelaire imagined himself as a member of a quasi-aristocratic elite of taste; later writers make this elite into the model for a broader international community. Borrowing from contemporary public sphere theory, I argue that the decadents constitute what Michael Warner calls a “counterpublic”—an oppositional social body made up of friends and strangers and formed by the production, circulation, and reception of texts. Lee defines the Renaissance not as a unified movement but as a series of contingent communities formed around wandering and hybridized literary and artistic forms. Pater’s protagonist Gaston imagines community in terms of the story of Pentecost, in which the Holy Spirit descends upon the apostles as tongues of flame, each speaking the native language of the multi-ethnic group present at the event. Beardsley’s novel depicts the literally underground exile community of Venus and her retinue in the Hörsel, and addresses its readers by incessantly gesturing toward the familiar constellation of themes and rhetorical practices that had come to serve as shorthand for decadence. His work builds an address to the decadent counterpublic into its very composition.

My postscript, “Public Works,” finds a new idea about community in Mallarmé’s memorial sonnet for Baudelaire, “Le Tombeau de Charles Baudelaire.” Eschewing the traditional imagery of monstrous flowers and exotic landscapes that dominated the nineteenth-century reception of Baudelaire, Mallarmé describes the poet in terms of sewers, street lamps, and public cemeteries. I see these images as evidence of a break from the decadent repudiation of modernity and a move toward a more inclusive notion of the relationship between poets and their audience. Like a public work, the poet provides material support for the community, a crucial means by which it can come to recognize its shared interests.