Читать книгу Behind the Mask: The Life of Vita Sackville-West - Matthew Dennison, Matthew Dennison - Страница 13

The Edwardians

Оглавление‘While he was still an infant John learned not to touch glass cases and to be careful with petit-point chairs. His was a lonely but sumptuous childhood, nourished by tales and traditions, with occasional appearances by a beautiful lady dispensing refusals and permissions …’

Violet Trefusis, Broderie Anglaise, 1935

‘IN LIFE,’ WROTE Vita Sackville-West in her best-known novel, The Edwardians, ‘there is only one beginning and only one ending’: birth and death.1 So let it be in this retelling of Vita’s own life.

Imagine her as a newborn baby, as she herself suggested, ‘lying in a bassinette – having just been deposited for the first time in it … surrounded by grown-ups … whose lives are already complicated’.2 The bassinette stands temporarily in her mother’s bedroom. The grown-ups are Mrs Patterson the nurse and Vita’s mother and father, Victoria and Lionel Sackville-West. We have already seen something of the complications: more will reveal themselves by stages.

In the early hours of 9 March 1892, the grey and green courtyards of Knole were not, as Vita later described them, ‘quiet as a college’.3 Howling and shrieking attended her birth. Outside the great Tudor house, once the palace of the Archbishop of Canterbury, once a royal palace and expansive as a village with its six acres of roof, seven courtyards, more than fifty staircases and reputedly a room for every day of the year, darkness hung heavy, ‘deepening the mystery of the park, shrouding the recesses of the garden’;4 the Virginia creeper that each year crimsoned the walls of the Green Court clung stripped of its glowing leaves. Inside, a night of turmoil dragged towards dawn. Dizzy with her husband’s affection, less than two years into their marriage, Vita’s mother confessed to having ‘drunk deep at the cup of real love till I felt absolutely intoxicated’:5 not so intoxicated that the experience of childbirth was anything but terrible. Its horrors astonished Victoria Sackville-West. She wept and she yelled. She begged to be killed. She demanded that Lionel administer doses of chloroform. It was all a hundred times worse than this charming egotist had anticipated. Lionel could not open the chloroform bottle; Mrs Patterson was powerless to prevent extensive, extremely painful tearing. And then, within three quarters of an hour of giving birth, she succumbed to ‘intense happiness’. Elation displaced agony. She was dazzled by ‘such a miracle, such an incredible marvel’: ‘one’s own little baby’. She was no stranger to lightning changes of mood.

Her ‘own little baby’ was presented to Victoria Sackville-West by her doting husband. Like a precious stone or a piece of jewellery, Vita lay upon a cushion. Her tiny hands, her miniature yawning, entranced her mother. So, too, her licks and tufts of dark hair. Throughout her pregnancy Victoria had been certain that her unborn child would be a daughter. Long before she was born, Victoria and Lionel had taken to calling her Vita (they could not refer to her as ‘Baby’ since ‘Baby’ was Victoria’s name for Lionel’s penis); her wriggling in the womb had kept Victoria awake at night. On the day of Vita’s birth, Victoria headed her diary entry ‘VITA’: bold capitals indicate that she considered the name settled, inarguable. It was, of course, a contraction of Victoria’s own name, just as the daughter who bore it must expect to become her own small doppelgänger. For good measure Victoria christened her baby Victoria Mary. Mary was a sop to the Catholicism of her youth. It was also a tribute to Mary, Countess of Derby, Lord Sackville’s sister, who had once taken under her wing Pepita’s bastards when first Lord Sackville brought Victoria and her sisters to England. Vita was the only name she would use. Either way, the identities of mother and child were interwoven. Even-tempered and still infatuated, Lionel consented.

And so, at five o’clock in the morning, in her comfortable Green Court bedroom with its many mirrors and elegant four-poster bed reaching right up to the ceiling, Victoria Sackville-West welcomed with open arms the baby she regarded for the moment as a prize chattel. ‘I had the deepest gratitude to Lionel, who I was deeply in love with, for giving me such a gift as that darling baby,’ she remembered many years later.6 She omitted to mention the lack of mother’s milk which prevented her from feeding Vita: her thoughts were not of her shortcomings but her sufferings. ‘I was not at all comfy,’ she recorded with simple pique. She was ever self-indulgent. The combination of intense love, possessiveness and an assertive sort of self-absorption imprinted itself on Vita’s childhood. In different measure, those same characteristics would re-emerge throughout her life.

In the aftermath of Vita’s birth, Lionel Sackville-West retreated to his study to write letters. He may or may not have been disappointed in the sex of his child, for which Victoria, with a kind of sixth sense, had done her best to prepare him. On 9 March, he conveyed news of his new daughter to no fewer than thirty-eight correspondents. The habit of entrusting intense emotions to the page and ordering those emotions through the written word would similarly form part of Vita’s make-up. As would his daughter, Lionel wrote quickly but with care. Later he shared with her his advice on how to write well.

When Lionel was not writing he read. In the fortnight up to 27 March, he offered his French-educated bride an introduction to the works of Victorian novelist William Makepeace Thackeray. Beginning with The Book of Snobs, he progressed, via Vanity Fair, to The History of Henry Esmond. Appropriately it was Becky Sharpe, self-seeking heroine of Vanity Fair, ‘a wicked woman, a heartless mother and a false wife’, who captured Victoria’s interest. The women shared coquetry, worldliness, allure. In time Victoria would indeed prove herself capable of falsity, heartlessness and something very like wickedness. But it was the story of Henry Esmond that ought to have resonated most powerfully for Lionel and his family.

Victoria’s diary does not suggest that either husband or wife drew parallels between the novel and their own circumstances. Those are for us to identify. As the illegitimate son of an English nobleman, Henry Esmond is unable to inherit the estate of his father, Viscount Castlewood, and ineligible as a suitor for his proud but beautiful cousin Beatrix: the paths to happiness, riches, respectability and title are liberally strewn with thorns. As we have seen, the legal and social ramifications of illegitimacy would for a period dominate the married life of Lionel and Victoria Sackville-West: their affection did not survive the struggle. In turn, Vita’s own life would be shaped, indeed distorted, by her inability as a daughter to inherit her father’s title and estates. In the early hours of 9 March 1892, wind buffeted the beeches of Knole’s park, ‘dying in dim cool cloisters of the woods’ where deer huddled in the darkness;7 the grey walls of the house, which later reminded Vita of a medieval village, stood impassive. All was not, as Vita wrote glibly in the fictional account of Knole she placed at the centre of The Edwardians, ‘warmth and security, leisure and continuity’:8 in her own life it seldom would be. There were very real threats to the security of her infant world. In addition, it was ‘continuity’ that demanded the perpetuation of that system of male primogeniture which was to cause her such lasting unhappiness. She once claimed for Knole ‘all the quality of peace and permanence; of mellow age; of stateliness and tradition. It is gentle and venerable.’9 But that statement was for public consumption. On and off, what Vita expressed publicly and what she felt most strongly failed to overlap. She was born at Knole, but died elsewhere. She would struggle to reconcile that quirk of fate.

In the short term, within days of her birth, baby Vita’s left eye gave cause for concern. Boracic lotion cleared up the problem and Victoria Sackville-West complacently committed to her diary the similarity between the blue of her daughter’s eyes and those of her great-uncle by marriage, Lord Derby. A smoking chimney in Vita’s bedroom resulted in her being moved back into her mother’s room. It was a temporary solution. Victoria’s diary frequently omits any mention of her daughter, even in the first ecstatic days which she celebrated afterwards as more wonderful than anything else in the world. Her thoughts were of herself, of Lionel, of how much she loved him. Most of all she recorded the extent of his love for her. It would be more than a month before she witnessed for the first time Mrs Patterson giving Vita her bath, a sight that nevertheless delighted her. In the meantime she rested, cocooned and apparently safe in her husband’s adoration.

These were happy days, as winter gave way to spring and Vita made her first sorties outdoors. She was accompanied on these excursions by Mrs Patterson, by her father or her grandfather, Lord Sackville. As the little convoy passed, clouds of white pigeons fluttered on to the roof, startled by the opening and closing of doors. ‘You have to look twice before you are sure whether they are pigeons or magnolias,’ Vita remembered.10 March faded into April and ‘underfoot the blossom was/ Like scattered snow upon the grass’;11 in the Wilderness, close to Knole’s garden front, daffodils and bluebells carpeted the artful expanse of oak, beech and rhododendron. Sometimes, indoors, Vita was placed on her mother’s bed, with its hangings embroidered with improbably flowering trees, ‘and I watched her for hours, lying or sitting on my lap. Her little sneezes or yawning were so comic. I hugged her till she screamed.’ At other times, husband and wife lay next to one another with their baby between them. When Vita cried, Lionel walked up and down Victoria’s bedroom, cradling her in his arms. In time, when Vita had learnt to talk, ‘she used to look at each of us in turn and nod her head, saying “Dada – Mama –”. This went on for hours and used to delight us.’12

These are common enough pictures, albeit the surroundings were uncommonly sumptuous. The air was densely perfumed with a mix of Victoria’s scent (white heliotrope, from a shop off the rue St Honoré in Paris), potted jasmine and gardenias that stood about on every surface, apple logs in the grate and, on window ledges and tables, ‘bowls of lavender and dried rose leaves, … a sort of dusty fragrance sweeter in the under layers’: the famous Knole potpourri, made since the reign of George I to a recipe devised by Lady Betty Germain, a Sackville cousin and former lady-in-waiting to Queen Anne.13 Such conventional domesticity – husband, wife and baby happy together – is unusual in this chronicle of fragmented emotions. ‘She loved me when I was a baby,’ Vita wrote of her mother in the private autobiography that was published posthumously as Portrait of a Marriage.14 In her diary, which she kept in French, Victoria described her baby daughter as ‘charmant’, ‘adorable’, ‘si drôle’: ‘toujours de si bonne humour’ (always so good humoured). On 17 June, she and Vita were photographed together by Mr Essenhigh Corke of Sevenoaks. But it was Lionel’s name, ‘Dada’, that Vita uttered first. It was 4 September. She was six months old.

Victoria’s diary charts Vita’s growth and progress. Some of it is standard stuff. There are tantalising glimpses of the future too. On 19 April 1892, Victoria opened a post office savings account for her daughter. Her first deposit of £12 was partly made up of gifts to Vita from Lionel and Lord Sackville. The sum represented the equivalent of nearly a year’s wages for one of Knole’s junior servants, a scullery maid or stable boy. Until her death in 1936, Victoria would continuously play a decisive role in Vita’s finances: her contributions enabled Vita to perpetuate a lifestyle of Edwardian comfort. Later the same year, Victoria introduced her baby daughter to a group of women at Knole. Vita’s reaction surprised her mother. Confronted by new faces, she behaved ‘wildly’ and struggled to get away. It is tempting to witness in her response first flickers of what the adult Vita labelled ‘the family failing of unsociability’.15 In Vita’s case, that Sackville ‘unsociability’ would amount to virtual reclusiveness.

The faces little Vita loved unhesitatingly belonged to her dolls. Shortly after her first birthday, Victoria made an inventory of her daughter’s dolls. It included those which she herself had bought at bazaars, a French soldier and ‘a Negress’ given to Vita by Victoria’s unmarried sister Amalia, as well as Scottish and Welsh dolls. ‘Vita adores dolls,’ Victoria wrote. In the ‘Given Away’ column of her list of expenses at the end of her diary for 1896, she included ‘Doll for Vita’, for which she paid five shillings. It is the only present Victoria mentions for her four-year-old daughter and contrasts with the many gifts she bestowed on her friends, her expenditure on clothing and the sums she set aside for tipping servants. Happily Vita could not have known of this imbalance. The following year she was photographed on a sturdy wooden seat with three of her dolls, Boysy, Dorothy and ‘Mary of New York’. Wide-eyed, Vita gazes uncertainly at the viewer. She is wearing a froufrou bonnet reminiscent of illustrations in novels by E. Nesbit; her ankles are neatly crossed in black stockings and buttoned pumps. She was two months short of her fifth birthday then and had ceased to ask her mother when she would bring her a little brother;16 she was still too young to be told of Victoria’s fixed resolve that she would rather drown herself than endure childbirth for a second time. Vita’s dolls had become her playmates and surrogate siblings. She had quickly grown accustomed to being alone: eventually solitude would be her besetting vice. For the moment her favourite doll was tiny and made of wool: Vita called him Clown Archie. He was as unlike ‘Mary of New York’, with her flaxen curls and rosebud mouth, as Vita herself, though there was nothing clown-like about the serious, dark-haired child. There never would be.

By the age of two, Vita was a confident walker. Earlier her grandfather had described to Victoria watching her faltering progress across one of Knole’s courtyards. On that occasion a footman attended the staggering toddler. In the beginning, Vita’s world embraced privilege and pomp. ‘My childhood [was] very much like that of other children,’ she afterwards asserted, itemising memories of children’s games, dressing up and pets.17 She was mistaken. Granted, there were universal aspects to Vita’s formative years: her love for her dogs and her rabbits; her fear of falling off her pony; her disappointment at the age of five, on witnessing Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession from the windows of a grand house in Piccadilly, that the Queen was not wearing her crown; her frustration at her parents’ strictures; even the ugly, homemade Christmas presents she embroidered for Victoria in pink and mauve. Too often her childhood lacked a run-of-the-mill quality. Hers was a distinctive upbringing, even among her peers. Its atypical aspects shaped her as a person and a writer; shaped too her feelings about herself, her family and her sex; shaped her outlook and her sympathies, her moral compass, her emotional requirements.

The trouble lay mostly with her mother. At thirty, recovering at her leisure from her confinement, Victoria Sackville-West remained beguilingly contrary; she had not yet been wholly spoiled. On the one hand she was capricious and snobbish (she described Queen Victoria as looking ‘very common and red-faced’18); on the other she was passionate and romantic, still the same eager, loving young woman who had confided to her diary with cosy delight, ‘Every day the same thing, walking … reading, playing the piano, making love’; still capable of enchantment.19 With her hooded dark eyes and hair that tumbled almost to her knees, she was lovely to look at. In the right mood, she was exhilarating company. Like Juliet Quarles in Vita’s novel The Easter Party, ‘she was irresponsible, unstable, intemperate, and a silly chatterer – but … under all these things she possessed a warm heart’.20 In time the combination of beauty, wealth and position encouraged less attractive facets to her character, but this illegitimate daughter of a poor Spanish dancer had yet to forget her good fortune in marrying her cousin. Hers was the zeal of a convert, leavened at this stage with apparently boundless joie de vivre: she embraced with gusto the life of an aristocratic chatelaine that had come to her like the happy ending to a fairy tale. As she herself repeated with justification, ‘Quel roman est ma vie!’ (My life is just like a novel). No one ever persuaded her to relinquish the heroine’s role.

Victoria’s year consisted of entertaining at Knole, country house visits and extended Continental holidays; her favourite days were those she spent alone with Lionel. These were leisurely days of flirtation and passionate lovemaking, of arranging and rearranging the many rooms she thrilled to call her own. She papered one room entirely with used postage stamps and made a screen to match. She installed bathrooms, the first for Lord Sackville, one for herself and another for Vita, close to the nursery. Along the garden front of the house, she rearranged furniture in the Colonnade Room to complete its transformation into an elegant if draughty sitting room. Its walls were painted in grisaille with grand architectural trompe l’oeil; seventeenth-century looking glasses and silver sconces threw light on to deep sofas. There Vita’s fifth birthday was celebrated with a Punch and Judy show; Vita dressed on that occasion with appropriate smartness in ‘an embroidered dress with Valenciennes insertion over [a] blue silk slip’, the sort of dress Victoria herself might have worn.21 As would her daughter, Victoria Sackville-West exulted in her splendid home. ‘Everybody says that I made Knole the most comfortable large house in England, uniting the beauties of Windsor Castle with the comforts of The Ritz, and I never spoilt the real character of Knole,’ she claimed for herself.22 Knole became her passion and filled her with a pride that was essentially vanity; she delighted in her ‘improvements’ to its vast canvas. ‘No one knew how, when the day was over and the workmen had gone home, she would lay her cheek against the panelling, marked like watered silk, and softer to her than any lips,’ imagined one of her observers.23 She had no intention of allowing motherhood to unsettle a routine that suited her so admirably. Inevitably, her manner of life affected her daughter.

Vita’s first Christmas was spent in Genoa. It was a family party of Victoria, Lionel, Lord Sackville, Vita, and Vita’s nurse, Mrs Brown. After Christmas, Mrs Brown took Vita to the South of France to stay with Victoria’s former chaperone, Mademoiselle Louet, known as Bonny; Lionel and Victoria continued on to Rome. Vita’s parents did not cut short their travels in order to celebrate her first birthday in March 1893: they were more than 1,600 miles from their baby daughter, in Cairo. In subsequent years they exchanged Cairo for Monte Carlo, their destination for Vita’s third, fourth and sixth birthdays. On those occasions Vita remained at Knole. On 9 March 1896, Victoria enumerated in her diary her losses and winnings, and those of Lionel, at the Casino: only as a parting shot did she note ‘Vita is four today.’ She did not suggest that she missed her daughter or regretted their separation; on the same day two years later, she admitted: ‘I think so much of my Vita today.’24 Every year there were visits to nearby London and a trip to Paris in the spring, ‘with the chestnut trees coming out and the spring sunshine sparkling on the river’.25

Accommodated within this routine, Vita’s childhood was by turns permissive and repressive. From infancy she was frequently left alone at Knole with her shy and silent grandfather. Lord Sackville believed in fairies. Morose and uncommunicative in adult company, he enjoyed the companionship of a tame French partridge and a pair of ornamental cranes called Romeo and Juliet, who accompanied him on his walks outdoors. His presence in Vita’s early years was benign if detached. Together they played draughts in the hour after nursery tea: as time passed, a shared antipathy to parties and smart society types sharpened their bond. Vita endeavoured to please her grandfather: ‘She is very busy gardening and cultivates mostly salad and vegetables for her Grand Papa,’ noted Victoria when Vita was eleven.26 Nurses and governesses oversaw Vita’s days; they were overseen in turn by Victoria, whose volatility ensured that none remained long at their post and that each dismissal could be traumatic and painful for Vita. When Vita was five, ‘Nannie’ was dismissed for theft. The truth was somewhat different. After the unexplained disappearance of three dozen quail, ordered for a dinner party, Victoria decided that Nannie had secretly consumed the entire order and acted accordingly.

With her parents abroad, as soon as she could walk Vita was free to lose herself in the self-contained fastness of Knole. She remembered ‘[splashing] my way in laughter/ Through drifts of leaves, where underfoot the beech-nuts/ Split with crisp crackle to my great rejoicing’.27 She climbed trees and stole birds’ eggs. She ran wild in ‘wooded gardens with mysterious glooms’ and on one occasion she fell into a wishing well. Indoors, even the frayed and faded curtains of Knole’s state rooms possessed a peculiar power of enchantment over her. After nightfall, beginning as a small child, she wandered through the rooms with only a single candle to hold fear at bay. Hers was a playground like few others.

The company of her mother, ‘maddening and irresistible by turns’,28 was predictably more stringent. Victoria’s sharp tongue was quick to wound, particularly on the subject of Vita’s looks, which proved an ongoing source of disappointment. ‘Mother used to hurt my feelings and say she couldn’t bear to look at me because I was so ugly’:29 it was Vita’s hair, with its stubborn resistance to curling, that exercised Victoria above all. She may have spoken more from pique than conviction – on 20 February 1903 she recorded in her diary, ‘The drawing of Vita by Mr Stock is finished and is quite pretty, but the child is much prettier and has far more depth and animation in her face;’30 it was all the same to Vita. Vita subsequently categorised her mother ‘more as a restraint than anything else in my existence’,31 but as a small child she delighted her with her quick affection and her loving nature. ‘She is always putting her little arm round my neck and saying I am the best Mama in the world,’ Victoria wrote on 1 August 1897.32 Vita grew up to regard her mother as compelling but incomprehensible: she dreaded her unpredictability and her ability to humiliate with a look or word. ‘She wounded and dazzled and fascinated and charmed me by turns.’33 Mutual misunderstanding coloured their relationship almost from the first: Vita was probably thinking of her mother when, in an essay about art composed in her late teens, she wrote, ‘It is possible, and indeed common, to possess personality allied to a mediocre soul.’34 In one letter, written in a round, childish hand, Vita implored Victoria to ‘forgive me. Punish me, I deserve it, but forgive me if you can and please don’t say you are sorry to have me and go on loving me.’35 Vita learned from Victoria that so-called loving relationships could embrace indifference, pain and even hatred, and that equality was not assured between partners in love. As she wrote in 1934 of one particularly mismatched couple in her novel The Dark Island, ‘She liked him, yet she hated him. She was surprised to find how instantly she could like and yet hate a person, at first sight.’36 For Vita that model of loving and hating existed in the first instance not in stories but her family life. It was a dangerous lesson.

It was Victoria, not Lionel, who administered punishments, and Victoria who ordered Vita’s life. When Vita was five, Victoria forced her to eat dinner upstairs: ‘she is always eating raw chestnuts and they are so bad for her’.37 Instead she insisted on simple food typical of nursery regimes of the period; Vita’s particular hatred was for rice pudding. The following year, Vita was again punished by dining upstairs: the six-year-old tomboy with the post office savings account had escaped her nursemaid in Sevenoaks in order to buy herself a ball and a balloon. Accustomed to extravagant flattery and naturally autocratic in all her relationships, Victoria inclined to high-handedness: where Vita was concerned she expected obedience. As it happened, her treatment of her daughter hardly differed from her behaviour towards her husband or her father. In each case she preferred to jeopardise affection rather than yield control.

Until Vita was four, Knole was home not only to her parents and her grandfather, but also her Aunt Amalia, ‘very Spanish and very charming’ in one estimate,38 remembered by Vita only as ‘a vinegary spinster … [who] annoyed Mother by giving me preserved cherries when Mother asked her not to’.39 (She annoyed Victoria more with her constant requests for money. The women were temperamentally incompatible and ‘endless rows and quarrels’ made both miserable.40) Also in the great house, hugger-mugger within its far-flung walls and ‘rich confusion of staircases and rooms’,41 lived Vita’s other families: four centuries of Sackville forebears, ‘heavy-lidded, splenetic’,42 preserved in heraldic flourishes and the rows of portraits in which Vita would glimpse ‘our faces cut/ All in the same sad feature’;43 and Knole’s servants and retainers. All influenced the small girl in their midst.

From the outset of her marriage, Victoria Sackville-West had set about rationalising Knole’s running costs. By 1907, she would successfully reduce the annual household expenditure by a third to £2,000.44 She did so while retaining a staff of sixty, including twenty gardeners; their combined wage bill cost her father and afterwards her husband a further £3,500.45 Few of these servants were known personally to Victoria, Lionel or Lord Sackville, or even recognised by them by sight. To Vita, free to explore regions of the house her parents seldom visited, they formed an extended kinship.

‘As a mere child, I was privileged. I could patter about, between the housekeeper’s room and the servants’ hall,’ Vita recalled in an article written for Vogue in 1931. ‘The Edwardians Below Stairs’ examines the elaborate staff hierarchies of her childhood. It also demonstrates how much of Vita’s time was spent among Knole’s servants, whom she knew by name, who shared her games and who omitted to lower their voices or silence their gossip in front of the dark-haired little girl who moved among them so easily. ‘I could help to stir the jam in the still-room or to turn the mangle in the laundry; I could beg a cake in the kitchen or a bottle of cider in the pantry; I could watch the gamekeeper skinning a deer or the painter mixing a pot of paint; my comings and goings remained unnoticed; conversation and comment were allowed to fall uncensored on my childish ears.’46 As Vita wrote of Sebastian and Viola in The Edwardians, ‘As children in the house, they had of course been on terms of familiarity with the servants, particularly when their mother was away.’47 So it was in her own case.

On the surface Vita’s childhood world was one of order and stability. Foresters cut timber and sawmen sawed logs – different lengths for different fires. Melons, grapes and peaches ripened in hothouses. Victoria’s guests enjoyed clean linen sheets daily; the flowers in their rooms were rearranged with similar frequency. Extravagance was endemic, splendid in its excess – as Vita remembered it in The Edwardians, ‘the impression of waste and extravagance … assailed one the moment one entered the doors of the house’.48 It contributed the necessary note of magnificence to this feudal environment of fixed places and shared loyalties. For Knole and its denizens, the world of 1892 appeared to differ from that of 1592 only in refinement and ease: given the estate’s modest income, it was a gorgeous charade. On the shell of Victoria’s pet tortoise, as it shuffled between sitting rooms, glittered her monogram, a liquid swirl of diamonds. It was a fantastical detail, afterwards appropriated by Evelyn Waugh in the lushest of his novels, Brideshead Revisited.

That the childish Vita should take for granted these insubstantial cornerstones of her parents’ existence is inevitable. Her memories indicate something more, a window on to Vita’s position as Knole’s only child: at home upstairs and downstairs, nowhere fully at home, everywhere proprietorial, keenly aware of her connection to the house and its history – as she herself offered, ‘Small wonder that my games were played alone; …/ I slept beside the canopied and shaded/ Beds of forgotten kings./ I wandered shoeless in the galleries …’49 Knole dominates all Vita’s memories of her childhood. She regarded it as her own munificent present and disdained to share it; later she would claim that a house was ‘a very private thing’.50 It was also an irresistible compulsion and seeped into so many of her thoughts. ‘At the centre of all was always the house,’ she wrote in an early story: ‘the house was at the heart of all things.’51 It occupied voids left by the absence of more conventional emotional outlets. That she learned early on that one day she must relinquish it, that as a girl she was prevented from inheriting what she already considered her own, served only to quicken those feelings which transcended ordinary love, feelings which went too deep to be put into words, so deep that throughout her life she hardly dared examine them.

A journalist in Vita’s lifetime described Knole as ‘too homely to be called a palace, too palatial to be called a home’52 – an outsider’s view. For Vita, even as a child, Knole was more than either home or palace. It was a living organism, ‘to others dormant but to me awake’:53 she lavished upon it the quick affection children usually reserve for their parents. ‘God knows I gave you all my love,’ she wrote later, ‘Scarcely a stone of you I had not kissed.’54 ‘So I have loved thee, as a lonely child/ Might love the kind and venerable sire/ With whom he lived,’ she claimed in a poem she dedicated to Knole.55

Finding her way through passages and galleries, crossing courtyards, peeping into workshops and domestic offices, what was Vita looking for and what did she see? Why did she give over her days to wandering and exploring, save for the pleasure of escaping her nursemaid or eluding her mother? At times, the connection she forged with Knole was the strongest bond of her life: to strengthen her conviction of reciprocity she endowed the house and its park with human attributes. ‘I knew thy soul, benign and grave and kind/ To me, a morsel of mortality,’ she wrote self-consciously, the night before she left Knole as a married woman for a new home of her own;56 in a later unpublished poem she went a step further and claimed that she was Knole’s soul. From a precociously young age, she was nourished and sustained by Knole’s accumulated memories: swaggering, picturesque, tragic or simply humdrum. The history she learned she read in its tapestries and portraits. In the first instance it was companionship Vita sought in the cavernous house: the romantic distraction of the past came next. ‘I knew all the housemaids by name … [and] was on intimate terms with the hall-boy … The hall-boy and I used to play cricket together.’57 They also indulged in wrestling bouts, for which Vita was punished by being made to keep her diary in French. But the hall-boy’s name is lost and we question the intimacy of those terms.

Day by day Vita absorbed an inflated, erroneous sense of Knole’s importance. Its place in British life – the prestige of her own family – overwhelmed her imagination. That sense persisted. A novel written when she was fourteen included the question, from father to son, ‘And you can bear that name, the name of Sackville, and yet commit a disgraceful action?’58 In fact, in the 850 years since Herbrand de Sackville had journeyed from Normandy with William the Conqueror, the Sackville achievement had been middling. Knole suggested otherwise, and it was Knole’s version of her family history that the young Vita unquestioningly imbibed and the mature Vita avoided revising.

As a child events conspired to delude her. In 1896, after Lord Sackville had persuaded the prime minister, Lord Salisbury, to make Lionel a temporary honorary attaché to the British embassy in Moscow, Lionel and Victoria set off from Knole to the coronation of Nicholas II of Russia; on the eve of departure their neighbours flocked to admire Victoria’s dresses and her jewels laid out for display like wedding presents. Two years later, the Prince and Princess of Wales lunched at Knole, in a party that included the Duke and Duchess of Sparta, heirs to the throne of Greece. Photographs show Vita and the Princess of Wales holding hands, an intimacy few six-year-olds could rival; they had stood side by side at the inevitable tree-planting ceremony. In his thank-you letter written afterwards, the prince admired Knole as ‘so beautifully kept’, a state he attributed to ‘the tender care “de la charmante Chatelaine!”’.59 In the summer of 1897, Victoria had recorded in her diary the visit to Knole of ‘Thomas the Bond Street jeweller’. She had summoned him to examine the silver. ‘He said that we had not the largest, but the best collection of silver in England.’60 Her life at Knole turned Victoria’s head. Knole turned Vita’s head too. In Vita’s case she knew no alternative.

The child shaped by parental absenteeism, maternal whim and her extraordinary surroundings was all angles and corners, ‘all knobs and knuckles’, ‘with long black hair and long black legs, and very short frocks, and very dirty nails and torn clothes’.61 She regarded her mother – indeed everyone outside the closed Knole–Sackville circle – with unavoidable hesitancy. Like the Godavarys in her later novella, The Death of Noble Godavary, she mistrusted any alien element within the family circle. From an early age, she took on her grandfather’s role of showing the house to visitors: the task exacerbated a tendency to unsociability. Although by modern standards Knole’s visitor numbers were low – on a ‘busy’ August day in 1901, the tally reached twenty-seven62 – Vita’s guide work stimulated her sense of possessiveness towards the house that would never be hers, and a rigid, atavistic pride in its glories. Showing the house was an exercise in showing off. Even as a teenager, travelling through Warwickshire en route to Scotland, Vita measured everything she saw against Knole’s yardstick. Of Anne Hathaway’s cottage she noted only its ‘very small, low rooms’, and she poured scorn on the idea that ruined Kenilworth Castle, covering three acres, had any claim to be considered ‘enormous’: ‘Knole covers between four and five acres.’63

The ‘tours’ she led even as quite a young child sealed the imaginative pact Vita made with Knole. She was reluctant and unskilled at making friends, sullen and shy confronted by unknown visitors, hostile and bullying to local children to the extent that ‘none of [them] would come to tea with me except those who … acted as my allies and lieutenants’.64 Knole superseded Clown Archie as her childhood love; perhaps it precluded – or prevented – other intimacies. ‘Vita belonged to Knole,’ Violet Keppel remembered; ‘to the courtyards, gables, galleries; to the prancing sculptured leopards, to the traditions, rites, and splendours. It was a considerable burden for one so young.’65

Unsurprisingly, given her surrounds, while her social instincts faltered, her imagination blossomed: her taste was for adventure. Vita was a scruffy, despotic, busy child. Her inclinations were starkly at odds with late-Victorian ideas about little girls. Victoria did her best. She commissioned elaborate fancy dress costumes, including a tinsel fairy dress, a May queen dress complete with a maypole made from wild flowers, and a flower-encrusted frock intended to transform Vita into a basket of wisteria (Victoria herself had been ‘very much admired’ when she wore a dress of similar design, with added diamonds, to a costume ball in 189766). It was not enough. Neither in appearance nor character would Vita achieve conventional prettiness and all that it implied; Victoria’s diary does not suggest she always troubled to sympathise with the daughter whose nature and instincts were so different from her own. Of a seaside holiday in August 1898, her mother recorded simply: ‘Vita was much impressed by seeing a runaway horse smashing a butcher’s cart.’67 Victoria and Lionel’s presents to Vita that year included a costly tricycle and a balloon. Even Vita’s greedy passion for chocolates and bonbons challenged Victoria’s ideas of appropriate behaviour. Concerned for her daughter’s complexion, and the figure she would later cut in the marriage market, Victoria ‘put away mercilessly what I thought was bad for her’.68

Although she was not aware of it, Vita learnt cruelty from her mother. It was not simply that isolation bred introspection or that Knole itself made Vita a dreamer, uninterested in those outside her gilded cage. Victoria’s exactingness threatened to deprive those closest to her both of autonomy and their sense of themselves. Her unconditional love for her daughter, whose birth she had regarded as a ‘miracle’, an ‘incredible marvel’, ceased with Vita’s babyhood. In time Vita learned to fear the mother whose love was so contrary, ‘so it was really a great relief when she went away’69: she never stopped loving her mother extravagantly. The family name for Victoria, ‘BM’ (Bonne Mama), contained no deliberate irony. ‘I love thee, mother, but thou pain’st me so!/ Thou dost not understand me; it is sad/ When those we love most, understand us least,’ Vita’s Chatterton exclaims in the verse drama she wrote about the doomed poet in 1909.70 Vita wrote the part of Chatterton for herself. Like many who are bullied, she responded by becoming herself a bully. Children invited to Knole to play with Vita were left in little doubt of the value she placed on their companionship.

Vita contributed a less-than-flattering anecdote to a volume of childhood reminiscences published at the height of her literary fame in 1932. It concerned the children of neighbours called Battiscombe, four girls and a boy, and happened at the beginning of the Second Boer War in 1899. Vita befriended the boy, Ralph. ‘The four girls were our victims’, forced to impersonate Boers. Together Vita and Ralph Battiscombe tied the girls to trees, thrashed their legs with nettles and blocked their nostrils with putty.71 Vita dressed for this activity in a khaki suit in which she masqueraded as Sir Redvers Buller, a popular military commander in South Africa and winner of the Victoria Cross. At her mother’s insistence, and much to Vita’s irritation, the suit had a skirt in place of trousers. The girls, she insisted in 1932, enjoyed their ordeal ‘masochistically’. She was equally clear about the sadistic pleasure she derived from her own part in this horseplay. For her seventh birthday that year, according to Victoria’s diary, Vita had received only presents of model soldiers. Within a year her toy box included guns, swords, a bow and arrow, armour and a fort for the soldiers. Seery bought her a cricket set. It ranked alongside her football among her prized possessions. ‘I made a great deal of being hardy, and as like a boy as possible,’ she wrote in 1920.72 She described a Dutch museum full of ‘all kinds of odds and ends: instruments of torture … old carriages’ as ‘a place where one could spend hours’.73 Forgotten were Clown Archie and his fellows. She composed a single poem about a doll. It was written in French in 1909 and called simply ‘La Poupée’. She invested more of herself in her subsequent biography of Joan of Arc. Like Vita, the tomboyish French saint fought her battles in armour and men’s clothing: brave, zealous, uncompromising. ‘One wonders what her feelings were, when for the first time she surveyed her cropped head and moved her legs unencumbered by her red skirt,’ Vita mused.74

Throughout her life Vita would appear easy with the inevitability of inflicting pain. There was a thoughtlessness to much of her cruelty, just as there was to Victoria’s. From Victoria, Vita had learnt that pain and suffering were implicit in the complicated experience of love. ‘Pain holds beauty in a fiery ring/ Much as the wheelwright fits the hissing tyre/ White-hot to wooden wheel,’ she wrote later.75 In a short poem, ‘The Owl’, she admired a similar combination: ‘Such beauty and such cruelty were hers,/ Such silent beauty, taloned with a knife.’76 All the principal relationships of Vita’s life – with her mother, with her husband Harold Nicolson, with Violet Keppel and a host of subsequent lovers, as well as with Knole – included this negotiation between positive and negative. The surprise is that she herself remained highly sensitive and easily wounded.

In keeping with her cruelty and her sensitivity, Vita also retained the habit, learnt in childhood, of secrecy. ‘Secrecy was my passion,’ she confessed.77 She later suggested that the passion for secrecy was the natural state of childhood.78 She avoided punishment as a small child by hiding under the pulpit in Knole’s Chapel, which lay within easy reach of her bedroom; as a teenager she resorted to code for those parts of her diary she meant to be private; later, in order to foil her mother, she wrote her diary entirely in Italian. Secrecy was Vita’s retreat: it inspired neither guilt nor reflection. Instead she excused it on grounds of heredity: ‘it’s a trait I inherit from my family. So I won’t blame myself excessively for it.’79 But while the family she referred to meant Lionel and the Sackvilles, the secretive impulse she developed as a child arose in response to the non-Sackville aspect of her upbringing, Vita’s understanding of her mother’s uncontrolled, unmannerly ‘Spanish’ emotionalism, which frightened and, over time, alienated her and forced her to keep her own counsel. For all her unwitting cruelty, Vita was seldom histrionic. The instinct for concealment, her dislike of ‘scenes’, were legacies of her childhood. As one future lover would remember, ‘She did demand peace and quiet … no rows. Certainly no inquisitiveness …’80

It seems surprising that Vita claimed subsequently that her memories of her childhood were hazy. As early as February 1912, weeks short of her twentieth birthday, she wrote to her future husband Harold Nicolson a selective description of her growing up that excluded more than it confided. It revealed what we know already, that like all children of her class, Harold included, Vita had led a double life: that of her parents’ daughter and that of the girl entrusted to a shifting cast of nurses and governesses. In addition, in Vita’s case, was the interior life of an only child who, inspired by her home and by loneliness, absented herself into daydreams and make-believe. As she grew older, while her parents travelled, Vita mastered time travel. She spirited herself into moments of Knole’s past, at one with the portraits and historic artefacts which surrounded her: the silver furniture made for James I in the King’s Room; the paintings by Holbein, Frans Hals, Van Dyck and Gainsborough; the heraldic leopards which prompted her to verse (‘Leopards on the gable ends, Leopards on the painted stair’); the white-painted rocking horse belonging to the 4th Duke of Dorset, an object doubly endowed in Vita’s eyes since the duke’s tragic early death in the hunting field had resulted in Knole’s inheritance by his sisters, a period of female ownership spanning half a century. Her spirited reveries excluded her parents. Often she dressed up, as in those Boer War games with the Battiscombes, fought in trenches among the rhododendrons; actually and metaphorically she would go on dressing up for much of her life. At the outset, the performance was for herself, Vita as player and Vita as audience.

As a writer, Vita seldom dwelt on the subject of childhood. Even the stories she wrote as a child focused on adults. Her poetic description of ‘children taken unawares’, ‘Arcady in England’, is an outdoor scene as much concerned with the lushness of an idealised autumn day as the particular nature of the children who catch the poet’s eye. For Vita’s upbringing was one in which, unusually alone, she learnt above all to observe; she forged few childish relationships, even within her family. Some things she saw clearly: the wonders of the great house that captivated her from infancy, ghosts of the past, the power of genius loci. Others she struggled to discern with any clarity throughout her life, among them her mother’s oscillation between absence and presence, affection withheld and affection lavishly bestowed, spite and charm. As in every childhood, happiness was balanced with unhappiness for Vita. As an adult she quoted one of her favourite forebears, Lady Anne Clifford: ‘the marble pillars of Knole in Kent … were to me oftentimes but the gay arbours of anguish’.81

Vita’s response to her dilemma was creative: she mythologised an existence she only partly understood. It was her own version of her mother’s ‘Quel roman est ma vie!’, but lacked the unqualified exuberance of Victoria’s joyful exclamation. For Vita, she and Knole and its whole population of relatives and servants became characters in a fable. She described her grandfather as ‘rather like an old goblin’. Contemptuously she listened to her mother ‘making up legends about the place, quite unwarrantable and unnecessary’, but acknowledged that ‘no ordinary mother could introduce such fairy tales into life’.82 Stalwartly and in silence, she worshipped her long-suffering father whom she imagined not as an individual but a type, ‘a pleasing man’83 – as Virginia Woolf described him, ‘the figure of an English nobleman, decayed, dignified, smoothed, effete’.84 Even the buildings themselves had an unreal quality, like a theatrical backcloth: ‘my little court [is] so lovely in the moonlight. With its gabled windows it looks like a court on a stage, till I half expect to see a light spring up in one window and the play begin.’85 When at length Vita devised a role for herself, she existed in a mythical tower, part heroine, part observer. At Sissinghurst thirty years on, she made good that pretence. Her sense of life as a performance – theatrical and containing elements of make-believe – began much earlier.

Victoria rejoiced in a reality that surpassed any romantic novel: Vita transformed the reality of her unsatisfactory childhood into a personal fiction. It was one way of placing herself centre stage and making sense of her fellow actors; the process also implied distance. These impulses of mythomania and detachment would remain part of Vita’s psyche until death. Early on, albeit subconsciously, she resorted to fiction to clarify the business of living: later she recycled her own reality as the principal element of her fiction, and all her novels contain fragments of autobiography. Despite this, Vita was an honest child and naturally affectionate. For the most part, those traits too would endure.

Vita Sackville-West described the childhood of the Spanish saint, Teresa of Avila, in The Eagle and the Dove, published in 1943. Identifying Teresa’s favourite childhood pastime as ‘tales of adventure’, she warmed to her theme. Throughout her youth, Vita wrote, Teresa, along with her brother Rodrigo, ‘could think of nothing but honour and heroism, knights and giants and distressed ladies, defeated evil and conquering virtue; they even collaborated in composing a story of their own, modelled on these lines’.86

Vita’s was a life of storytelling. Aspects of her poetry, the fiction she wrote in order to make money, her nonfiction and much of her journalism have a strong narrative content; ditto her diary, in which events, appointments and people take the place of analysis or self-searching. Honour, heroism and conquest – sometimes metaphorical, sometimes reimagined – all find a place within the stories Vita spun; invariably she projects herself into the person of her hero. She glimpsed an echo of these vigorous heroics in the youthful St Teresa, a fiery and imaginative aristocratic teenager sent to the Convent of Santa Maria de Gracia after suspicions of a lesbian affair. It was this swashbuckling quality that endeared Teresa to her: similar feelings coloured Vita’s interpretation of seventeenth-century writer Aphra Behn and French saint Joan of Arc, whose biographies she also wrote. Vita’s juvenilia, written in her teens, includes ‘tales of adventure’: so too the more fanciful of her mature fiction, for example, Gottfried Künstler and The Dark Island. The greatest adventure was writing itself. It would remain so. ‘I do get so frightfully, frenziedly excited writing poetry,’ she once admitted. ‘It is the only thing that makes me truly and completely happy.’87 Predictably her happiness was shared by neither of her parents, both of whom disapproved.

At Knole, Vita wrote at a small wooden table in a summerhouse shaded by tall hedges. It overlooked the Mirror Pond and the sunken garden. Previously, it had served as her schoolroom. She did her lessons there: by the time she was ten, essays written in English, French and German on geography and history (Norway and Sweden, ‘L’Amérique du Nord’, Charlemagne, Charles I, William and Mary, Trafalgar), as well as exercises in creative writing (‘Un jour de la vie d’un petit Chien’). Vita cannot have enjoyed these lessons unreservedly: she remembered at moments of boredom or revolt gouging the table’s wooden surface with the blade of her pocketknife.

Initially she wrote what she subsequently described as ‘historical novels, pretentious, quite uninteresting, pedantic’.88 She wrote plays, too, inspired by history or by plays she had seen or read and particularly enjoyed. She wrote at speed. Fully bilingual until her late teens, she was as comfortable in French as in English; she worked with an easy facility, as if writing were for her the most natural thing imaginable. Inspiration never failed her: ‘the day after one [book] was finished another would be begun’.89 In 1927 she quoted a contemporary assessment of Aphra Behn: ‘her muse was never subject to the curse of bringing forth with pain, for she always writ with the greatest ease in the world’.90 So it was, at the outset of her career, for Vita. Rapidly, the pile of lined Murray’s exercise books and foolscap ledgers mounted. All were neatly written in the clear, unselfconscious, undecorated handwriting that scarcely changed until her death. She dated her efforts, noting the days she began and ended. Sometimes a comment recurs in the margin: V. E. – ‘my private sign, meaning Very Easy; in other words, “It has gone well today.”’91 From the outset Vita’s manuscripts were remarkable for their tidiness and the absence of large-scale corrections and alterations. She claimed that she began writing at the age of twelve and ‘never stopped writing after that’.92 She identified as a catalyst Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac.

When Vita first encountered it, Rostand’s play was relatively new: it was written in 1897. By her twelfth birthday seven years later, she knew all five acts by heart. It was a work custom-made for this proud, fierce, boyish but still, on occasion, sentimental young woman of gnawing insecurities, a story of a nobly born soldier-poet, swashbuckling by nature but crippled by self-doubt on account of his enormous nose: ‘My mother even could not find me fair … and, when a grown man, I feared the mistress who would mock at me.’ The play is set in seventeenth-century France. The teenage Vita followed Rostand’s lead and repeatedly returned to the grand siècle: in Richelieu, a 368-page historical novel she began in French in October 1907; Jean Baptiste Poquelin, a one-act comedy about Molière, also written in French the same year; and Le Masque de Fer, a five-act French drama about Richelieu and Louis XIII, written, like Cyrano, in a poetic form resembling alexandrines. At the time Vita’s favourite writers were historical novelists Walter Scott and Alexandre Dumas: their shadows loomed large.

A portrait of Scott hung in Knole’s Poets’ Parlour, the room used by Lionel and Victoria as their family dining room. Vita’s early writing could never be anything but self-conscious. ‘She allowed her readings of … heroic romances to … flavour her interpretation of her hero with an air of classic chivalry,’ the mature Vita wrote of Aphra Behn’s story of thwarted love and racial prejudice, Oroonoko. ‘Oroonoko resembles those seventeenth-century paintings of negroes in plumes and satins, rather than an actual slave on a practical plantation.’93 It was a criticism she might have levelled at her younger self. The teenage Vita admired heroism, grand gestures, the dramatic (and the melodramatic) impulse. ‘In our adolescence, I suppose we have all thought Ludwig [II of Bavaria] a misunderstood figure of extravagant romance,’ she reflected later; ‘in the sobriety of later years we see him to have been only an exaggerated egoist … who happened also to be a king.’94 Twice as a young woman she wrote about Napoleon, a suitably leviathan figure – in a novel, The Dark Days of Thermidor, and a verse drama, Le roi d’Elbe, both written in 1908. Both are exercises in historic romanticism.

In the beginning Vita approached her writing in a spirit of earnestness and painful sincerity: she described her adolescent self as ‘plain, priggish, studious (oh, very!)’.95 Her teenage notebooks include historical jottings, scene-by-scene breakdowns of her plays, and chapter summaries for novels. Heavily she puzzled over the nature of literature, the qualities necessary to write well and the purpose and requirements of art; essays from this time include ‘The difference between genius and talent’, and ‘The outburst of lyric poetry under Elizabeth’. ‘Sincerity is the only possible basis for great art,’ she offered sententiously;96 certainly her output lacked humour. Vita’s submergence in her self-appointed task was complete. She revelled in losing herself in an imaginary past; she was dizzy with the thrill of creation: here was an occupation to match her loneliness. Her adult self likened the experience to drunkenness. It was especially heady on those occasions when she turned her attention to family history.

Vita wrote her first ‘Sackville’ novel in 1906. The Tale of a Cavalier was inspired by Edward Sackville, 4th Earl of Dorset, for Vita ‘the embodiment of Cavalier romance’. His portrait by Van Dyck, in breastplate and striped vermilion doublet, hung in Knole’s Great Hall, constantly before her. The following year she wrote The King’s Secret. Its subject was Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset, minor poet, rake, lover of Nell Gwyn, latter-day patron of Dryden and friend of Charles II (Victoria described it as Vita’s ‘Charles II book’). The 6th Earl was largely responsible for the appearance of the Poets’ Parlour in Vita’s childhood. In addition to Scott, its panelled walls were crowded with portraits of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton and Dr Johnson, alongside Sackville’s friends and contemporaries Dryden, Addison, Congreve, Wycherley and Pope. Such an illustrious visual compendium provided a powerful spur to Vita’s sense of vocation.

The King’s Secret included a self-portrait: ‘a boy muffled up in a blue scarf … scribbling something in a ponderous book … His pen flowed rapidly over the paper … He wrote from morning till evening.’97 She called her alter ego Cranfield Sackville, the first of numerous masculine fictional self-representations. He wrote ‘in a little arbour situated in the garden at Knole’.98 As she worked, Vita remembered, ‘the past mingled with the present in constant reminder’,99 the former as tangible as the latter, she herself in her own words a fragment of an age gone by.100 Victoria queried Vita’s self-portrait: Cranfield she considered ‘more open, less reserved’ than Vita. Plaintively she confided to her diary the wish that her daughter could ‘change and become warmer-hearted’.101 By chance, a visit to Dover Castle on 18 July, midway through The King’s Secret, brought Vita to the last meeting place of Charles II and his sister Henrietta. ‘This is interesting to me, as I am just writing about their meeting!’ she noted.102 Her earliest approaches to fiction were the literary equivalent of method acting.

But it was from a less picturesque source that Vita drew her first literary income. In July 1907, she was one of five winners of an Onlooker competition to complete a limerick. Her prize was a cheque for £1. In her diary, fifteen-year-old Vita put a characteristically heroic spin on events: ‘This morning I received the £1 I had won in the “Onlooker” verse competition. This is the first money I have got through writing; I hope as I am to restore the fortunes of the family that it will not be the last.’103 She resorted to code to record her intention of restoring the family fortunes. A fitting ambition for this ardent Sackville scion, it was not one she intended to expose to her mother’s watchful gaze.

Predictably, opposition came from close to home: Vita’s parents. Lionel was too conventional to embrace the idea of a daughter whose writing was more than a diversion. Like the majority of upper-class Englishmen of the time he mistrusted intellectualism, particularly in women: Vita described life at Knole as ‘completely unintellectual … analysis wasn’t the fashion’.104 Lionel had sown his wild oats in marrying his illegitimate cousin; in the short term, there would be no further public transgressions. Even the eventual breakdown of his marriage was managed with relative decorum on Lionel’s part. In her diary Victoria noted the physical resemblance between father and daughter and Lionel’s pride in Vita; his only plan for her was marriage into a family like his own, preferably to an eldest son. More than anything he longed for her to embrace ‘normal and ordinary things’, among which he did not count writing.105

On the surface, Victoria showed more sympathy. Victoria was Vita’s chosen reader. ‘How marvellously well she writes!’ she admitted later. ‘Reading her calm descriptions fills me with admiration … No one can beat her at her wonderful descriptions of Nature, or analysing a difficult character.’106 But Victoria too mistrusted the intensity of Vita’s involvement with her writing. Pepita’s daughter was too parvenu to condone such evident disregard for the conventional preoccupations of the society she had married into. (Vita afterwards condemned these preoccupations as limited to parties and investments, pâté de foie gras and the novels of E. F. Benson.) Two years earlier Victoria had confided to her diary her relief that Vita was ‘getting a little more coquette and tidy’, suggesting a growing interest in clothes and appearances to match her own; it was a chimera. On 16 July 1907, while she continued to work on The King’s Secret, Vita’s parents finally made their feelings plain: ‘Mama scolded me this morning because she said I write too much, and Dada said he did not approve of my writing … Mother does not know how much I love my writing.’

Vita was mistaken. Both her parents saw the extent of her passionate engagement with her writing. They noted, for example, that the majority of her thirteenth birthday presents were books: as a counterbalance, their own present consisted of sumptuous squirrel furs.107 Yet, despite their disapproval, they did little to redirect Vita’s energies. By 1907, confronted by overwhelming evidence of Lord Sackville’s mismanagement, they had embarked on a course of unwelcome financial retrenchment which only the Scott bequest would resolve; Victoria’s troublesome siblings continued their carping demands for money and title which afterwards erupted into the succession case of 1910. Above all, Victoria and Lionel knew now that their marriage was broken beyond repair. If Lionel’s response was one of courteous indifference, Victoria’s emphatically was not. She was angry, hurt, uncomprehending. There would be no resolution. Their days of acting in unison were running out. For her twenty-first birthday, Victoria presented Vita with the Italian desk which remains today in her writing room at Sissinghurst.

On 8 April 1908, an ebullient Vita recorded in her diary, ‘We had the results of the exams at Miss Woolff’s. I am first in French literature, French grammar, English literature and geography, and I won the prize essay. Brilliant performance!’ Later that year she consolidated her position. ‘Prize essay day at Miss Woolff’s,’ she wrote on 16 December: ‘I won it (“Reminiscences of an Oak Tree”). I was also first in mythology!’ She won the same prize for the third time on 5 April 1909. The title on that occasion played to bookish Vita’s strengths: ‘Thoughts in a Library’.

By 1909, Vita was in her fourth and final year at Helen Woolff’s School for Girls in London’s South Audley Street. She had first attended classes there at the age of thirteen and pursued her studies thereafter during the autumn and Easter terms. At the same time, until July 1905, Victoria retained the services of Vita’s French governess of ‘such an uneven temper’, Hermine Hall.108 Vita continued to write outside school: her earliest surviving poems, along with fragments of poems, date from this period. Like Cyrano de Bergerac, Miss Woolff’s school was a catalyst in Vita’s life: it represented her first sustained participation in the world of her contemporaries outside Knole. Neither the curriculum studied nor Miss Woolff herself impacted significantly on her intellectual growth or her development as a writer. Nor did she much relish the company of her peers, dismissing in her diary ‘the average run of English girls’ as dull and stupid.109 Meanwhile Victoria oversaw her cultural education: on 13 February 1909, Vita attended a matinée of The Mikado; on 16 February she went to an organ recital in Westminster Abbey given by Master of the King’s Musick, Sir Walter Parratt; on the following day she was present at ‘a most interesting lecture on Madame Récamier’.

More compelling than anything Miss Woolff or Victoria offered was Vita’s unquenchable thirst for her writing. ‘There is writing, always writing,’ she remembered of this period:110 her best days resembled those of Cranfield Sackville, at work undisturbed in his garden arbour. Vita was an autodidact. In every area she prized most highly, from poetry to gardening, she was partly self-taught. Writing had the added attraction of temporarily screening Vita from her parents’ world of acrimony and threats of litigation: she excluded from her first fictions anything unheroic in her Sackville heredity. In Orlando, her fictional ‘biography’ of Vita, Virginia Woolf describes Orlando’s hope ‘that all the turbulence of his youth … proved that he himself belonged to the sacred race rather than the noble – was by birth a writer rather than an aristocrat’.111 Throughout her life, Vita thirsted for just such an acknowledgement. She was never brave enough to separate her two identities. At first an aristocrat who wrote, she became a writer whose work affirmed her own ideal of aristocracy. It was one of several conflicts in her nature.

Vita considered that she had worked hard at Miss Woolff’s. ‘I set myself to triumph at that school, and I did triumph. I beat everybody there sooner or later, and in the end-of-term exams, I thought I had done badly if I didn’t carry off at least six out of eight first prizes.’112 Her triumph transcended examinations. She did indeed earn the reputation for cleverness she had deliberately cultivated. It went some way towards softening the blow of her unpopularity, which she attributed to her moroseness, pedantry, priggishness and savagery, as well as an appearance of aloofness that she was at a loss to explain. There were other discoveries too. Among her fellow pupils were girls who fell in love with Vita.

As an adult, Vita seldom loved singly and was always, as one of her sons remembered, in love.113 Her childhood had been poor preparation for intimacy. Neither Victoria nor Lionel consistently gave her grounds to suppose herself the exclusive object of their affections. Victoria’s love was erratic, Lionel’s mostly implied. As Vita wrote of Shirin le Breton in The Dark Island, ‘It was not a particularly united family, and indeed was held together, as is the case in many families, less by the ties of affection than by those of convenience and convention.’114 Vita loved Knole and believed that Knole returned her love. Her attitude refuted that of Leonard Anquetil in The Edwardians: ‘Chevron [Knole] is really a despot of the most sinister sort: it disguises its tyranny under the mask of love.’115 Yet the house could not wholly replace more conventional relationships. When she was older, Vita wrote in one of the unpublished private poems she called diary poems: ‘The horrible loneliness of the soul makes one crave for some contact.’116 ‘Contact’ was not love, nor limited to a single donor or recipient. During her teenage years at Miss Woolff’s, Vita inspired, and partly reciprocated, the love of two classmates: Rosamund Grosvenor and Violet Keppel.

She had known them both before. Rosamund Grosvenor was an old familiar, Vita’s first friend, a relation of the Duke of Westminster. They were ten and six respectively when Rosamund first visited Vita at Knole in 1899. In his capacity as commander of the West Kent Yeomanry, Lionel had departed for South Africa and the Boer War, and Victoria worried that Vita would be lonely. Rosamund stayed for three days: Vita remembered only that her neatness and cleanliness contrasted with her own grubbiness. Until 1908, when her family moved away from Sevenoaks, Rosamund shared Vita’s morning lessons at Knole. Initially, theirs was a milk-and-water relationship. Vita complained in private of Rosamund’s ordinariness and lack of personality; Rosamund fell under the combined spell of Vita and Knole. Despite her four years’ seniority, Rosamund learned to adopt the role of supplicant. It may have come naturally to her or she may have realised that the Vita who prided herself on her hardiness and her resemblance to a boy could only be conquered by weakness. Fortunately for Rosamund, who by her late teens was deeply in love, she had good looks on her side. Her soft, creamy curvaceousness earned her the nickname ‘the Rubens lady’. Eventually it was Rosamund’s body, not her mind, which provoked a response in Vita. In her diary for 17 July 1905, she noted that Rosamund had gone swimming, noted too her appearance in a bathing costume ‘on the skimpy side’. Vita was thirteen, Rosamund seventeen. When their relationship progressed beyond girlish friendship, Vita was clear that, as far as she was concerned, its root was physical attraction: Rosamund was fatally uninterested in books.

Hero worship, and a tendency she could not resist to regard Vita as the living incarnation of centuries of Sackville swank, characterised Rosamund’s love. She revelled too in Vita’s Spanish blood, an association of exotic glamour which Vita herself exploited. Vita provoked a similar response in Violet Keppel: ‘All this, and a gipsy too! My romantic heart overflowed.’117 Rosamund addressed Vita as ‘Princess’; for Violet, Vita was her ‘Rosenkavalier’.118 Both names imply status, desirability, a prize.

Violet’s novel Broderie Anglaise offers a version of her relationship with Vita, whom she reimagines as a youthful peer, John Shorne. There is ‘a languid grace’ about Shorne, ‘a latent fire’. Like Vita, he bears a strong resemblance to his family portraits. His ‘face recalled so many others seen in frames and surrounded by a ruff, a jabot or a stock, a face that had been a type since 1500 … a hereditary face which had come, eternally bored through five centuries’.119 Like Rosamund, Violet romanticised Vita. Yet while Rosamund’s affection had the puppyishness of first love, Violet’s, even as a child, was characterised by an obsessive decisiveness. It was not, Vita insisted, ‘the kind of rather hysterical friendship one conceives in adolescence’:120 there was nothing exploratory about Violet’s feelings. Her emotional precocity was matched only by her determination. If Rosamund’s love for Vita resembled the blushing passions of a girls’ school story, Violet’s possessed from the beginning a more adult quality. Her decision that Vita was her destiny was virtually instantaneous and never rescinded. Decades later she underlined in her copy of The Unquiet Grave Cyril Connolly’s statement that ‘We only love once, for once only are we perfectly equipped for loving.’121 She had not needed a book to tell her that. Even at the end of her life, fragile and lonely in the Villa Ombrellino in Florence, Violet spoke of Vita in adulatory tones. When it happened, she became Vita’s lover through force of will. Vita was a mostly willing participant, but it was Violet who contrived their collision.

Their first meeting took place on a winter afternoon: Mayfair, 1905, a tea party of sorts for a girl friend with a broken leg, who remained in her bed. The only fellow guest Violet noticed at the bedside was Vita. Vita was thirteen, tall for her age, ungainly and unmannerly (Lionel had recently complained of her abruptness and her roughness). Violet was two years younger. Vita rebuffed her conversational gambits, Violet inwardly criticised Vita’s dress. Both were evidently curious. Violet persuaded her mother to invite Vita to tea; Vita’s mother was delighted and Vita went. Again their conversation was at cross purposes. Violet described Paris while Vita enlarged on her rabbits. They found common ground in inventorying aloud lists of their ancestors: as Vita explained later, in upper-class Edwardian society ‘genealogies and family connections … formed almost part of a moral code’.122 On Vita’s departure, Violet kissed her. At home Vita congratulated herself on having made a friend – this was so unusual that she sang about it in the bath – while Violet embarked on what would become a lengthy and at times inflammatory sequence of letters. Vita responded with more news of her rabbits and also her dogs: an Aberdeen terrier called Pickles and an Irish terrier predictably known as Pat. Nothing daunted, Violet poured out what Vita labelled ‘precocious letters on every topic in a variety of tongues, imaginative exceedingly, copiously illustrated, bursting occasionally into erratic and illegible verse’.123

Between letters Vita visited Violet at her parents’ house in Portman Square; Violet was invited to Knole. Portman Square, where Violet’s mother, Alice Keppel, played host to Edward VII as his mistress, suggested sex at its most discreet and profitable; Knole, with its whispering galleries of Sackville history, imparted romance, a thrill of derring-do glittering in dust motes. Vita’s shortcomings as a correspondent notwithstanding, for Violet it was a perfect combination. ‘I fell in love with John when I was eleven and a half – I swear that’s the truth – and for eight years I never stopped thinking about him,’ she wrote of Vita–John in Broderie Anglaise.124 In another novel, Hunt the Slipper, she suggested that ‘one never loves more passionately than at the age of ten’.125

Vita and Violet shared dancing and Italian lessons. In the spring of 1906 they were in Paris at the same time. In the apartment in the rue Laffitte, in front of an audience of Lionel and Victoria and Sir John Murray Scott’s French servants, they staged Vita’s play about the reign of Louis XIII, Le Masque de Fer. Vita took the part of the Man in the Iron Mask and was delighted when Seery’s cook burst into tears. Less competent a French speaker than Vita (she did not have the benefit of a French-convent-educated mother), Violet took French lessons. They began to talk to one another in French. There was a special excitement to the intimacy of addressing each other as ‘tu’. That sense of intimacy grew. In the spring of 1908, Violet told Vita she loved her, ‘and I,’ wrote Vita, ‘finding myself expected to rise to the occasion, stumbled out an unfamiliar “darling”’.126 Violet sought to make a pact of the exchange by presenting Vita with a ring when next they met. The ring had been a reluctant present to Violet from the Bond Street art dealer Sir Joseph Duveen when Violet was six. It was carved from red lava with the image of a woman’s head and had belonged to a Venetian Doge of the early Renaissance. The sixteen-year-old Vita composed a special entry in her diary and kept the ring lifelong.

Vita’s relationship with Violet Keppel changed the course of her life: she was slow to respond fully to overtures which, on Violet’s part, contained a sexual dimension almost from the start. This was not, Vita would claim, because she mistook Violet’s intentions. Violet was always unique among Vita’s friends: colourful and sophisticated; her ‘erratic’ friend, as she introduced Violet to Harold Nicolson; ‘this brilliant, this extraordinary, this almost unearthly creature’, as Vita described her at the height of their affair in 1920;127 the friend whose love she argued she had recognised immediately. She said that she had understood Violet’s early feelings for her as she had understood those of Rosamund, whom she had admitted she loved by the time she was fifteen. Her mother’s diary challenges such assertions of sexual maturity. ‘Vita and I had begun together The Woman in White,’ Victoria wrote on 21 September 1904; ‘I dropped it as the child’s mind is still too young and I am careful to keep her very pure-minded.’ She had confiscated The Count of Monte Cristo for the same reasons.

If Vita was aware of the nature of Rosamund and Violet’s feelings, she ought to have recognised that they were rivals. In the event she admitted no need to arbitrate between them. In this way, at the outset of her romantic career, she established a pattern which would continue, juggling multiple lovers with no apparent sense of conflict or disloyalty. ‘All love is a weakness … in so far as it destroys some part of our independence,’ says Sebastian in The Edwardians.128 For Vita, invariably more loved than loving, love would seldom compromise her independence. She exercised freedom of choice both romantically and sexually, countering Silas’s statement to Nan in her early novel The Dragon in Shallow Waters that ‘freedom goes when the heart goes’.129 Invariably she retained a clear conscience, and she did not often lose her heart.

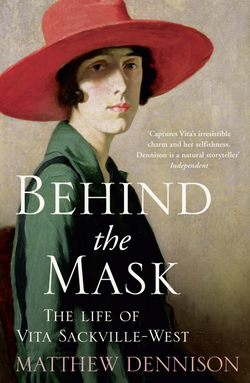

Vita did not return to Miss Woolff’s school in the autumn of 1909. Instead she went abroad with her mother and Sir John. Her extended visit to the Continent took in Germany, Austria, Poland and Russia. At Antoniny in the Ukraine, Vita experienced a last gasp of the ancien régime, staying with Count Joseph Potocki, ‘riding, dancing, laughing; living at a fantastic rate in that fantastic oasis of extravagance and feudalism, ten thousand horses on the estate, eighty English hunters, and a pack of English hounds; a park full of dromedaries; … Tokay handed round by a giant; cigarettes handed round by dwarfs in eighteenth-century costumes’.130 Potocki’s estate covered a hundred miles. Dazzled by splendour, aware of the poverty endured by all bar her host, Vita recognised an alternative, and disturbing, version of the tale of inheritance she had imbibed as Knole’s child. The inequalities shocked her. ‘That experience was really like going back to France before 1789,’ she wrote in 1944. ‘It was horrible; it was revealing.’ The travellers wound up in October in Paris, where Victoria ordered dresses for Vita at Worth. As her eighteenth birthday approached, her mother had different plans for Vita, who that year had begun her reluctant career as a debutante. ‘Party in the evening at Lady Jane Coombe’s,’ Vita had written laconically in her diary on 25 January: ‘Hated it.’ For Lionel and Victoria, whose ambitions for Vita’s marriage were considerable, it was an ominous beginning to her first season. Vita would discover, as she had predicted leaving Russia, a stultifying sense of confinement about the life that was now expected of her at home: ‘How shall I ever be able to live in this restricted island! I want expanse.’131 In the short term she did not rebel. She wrote out her protest in a new novel. In Behind the Mask, a story of modern marriage set in France, she dismissed ‘the whole business’ of the marriage market as ‘coarse and vulgar’.132

On 5 October 1905, Victoria Sackville-West had decided to make a new will. She had visited the family solicitor, Mr Pemberton of Meynell & Pemberton, back in March 1897, in order to formalise her intention of leaving ‘everything to Lionel in trust for Vita, till she marries with his consent; then he will give her the income of the capital’.133 On that occasion Vita was days short of her fifth birthday. By the time Victoria returned to the fray, her daughter was thirteen. Victoria explained her motives: ‘Now … I do not think I shall have another child, after all the precautions Lionel and I have taken.’134

Sexual intercourse ceased for Lionel and Victoria Sackville-West in 1904. Once it had formed the bedrock of this mismatched couple’s relationship. The decision was Victoria’s, her justification the weakness of her nervous system, as explained to her by her obliging physician Dr Ferrier. From now on, iron tablets rather than Lionel would be her medicine. Her husband was thirty-seven years old, active and highly sexed: previously Victoria had described him as ‘a stallion’, their lovemaking ‘delirium’. Lionel, for his part, had once thought Victoria ‘the very incarnation of passionate love’: ‘Her breasts are too delicious for words – round firm and soft with two darling little buttons which I adore kissing. She has the most magnificent hips and legs with the most ravishing little lock of hair between them which is as silky and soft as possible.’135 During the early years of their marriage, Victoria’s diary is full of sex: when, where and how often. In the beginning, the naughtiness of ‘Baby’ (Lionel’s penis) is a constant refrain. Sex forced the couple to miss morning appointments; it inconvenienced the servants; it kept Victoria awake at night; it bound them together.