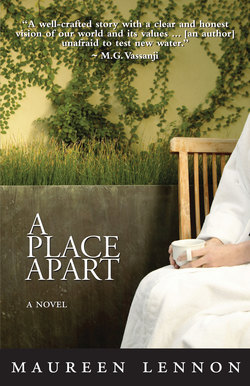

Читать книгу A Place Apart - Maureen Lennon - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 4

ОглавлениеCathy dried herself off, put her pyjamas back on, and stepped cautiously out into an empty hall. Her mother had vanished and the house had fallen silent again. Hurrying, she opened the hall closet where the cleaning supplies were kept, gathered up what she needed for her chores, and raced up to her room.

“Great news, huh?”

Cathy dumped all the aerosol cans and spray bottles and dusters into the middle of her unmade bed.

“Oh, Angela, I’ve got a job.”

“So I heard.”

“I’ve got something to do all summer.”

“Cool.”

“I can’t believe it. All of a sudden I feel so grown up.”

Cathy plunged into the closet and hung her wet underwear on a nail in the back corner.

“A summer job. I’ll have a bit of money and something to do.”

She popped back out and tore open a dresser drawer to begin changing into work clothes.

“I can go somewhere every day for two whole months.”

“Hot dog!”

“I’m so excited.”

“So I see.”

“I’ve always wanted to go away. For years, I’ve been thinking about it.”

“I’ve seen the pencil marks under your desk.”

“But I thought it wouldn’t be until I could go to university. But that’s still three years away.”

“Lucky break, huh?”

“But this is right out of the blue. It’s not the same as going away to live somewhere else, like residence, but it’s at least a start.”

Angela smiled. Cathy plunked herself down on the bed to pull on a pair of socks.

“It’s housekeeping ... for three priests ... at St. Alphonsis rectory ... across town.”

“I was there, remember?”

“It’s supposed to be old, but maybe it’s going to be really nice, like those parish churches in the old Christmas movies, you know? All that nice dark old woodwork, some of it halfway up the walls in some of the rooms, like the dining room, you know? I wouldn’t mind polishing all that.”

“You just might be out of your mind, you know?”

“I get to cook, too.”

“That’s always fun.”

“I know how to make sloppy joes, grilled cheese sandwiches, and tuna casserole.”

“Gotta start somewhere.”

“And I can barbecue things, steaks and chicken and burgers. I’m sure they’ll have a barbecue.”

“Well, you hope they’ll have a barbecue.”

“I’ve always wanted to try baked Alaska too. You know, it’s ice cream that gets baked inside a cake and it doesn’t melt?”

The whine of the vacuum cleaner suddenly started up in one of the downstairs rooms. Cathy saw that she was sitting motionless, gazing at herself in the dresser mirror. The side of her face was swollen, her eyes bloodshot, and one finger was bound in white tape.

She got up and opened the two small windows in the room. The droning of several lawn mowers and the smell of fresh-cut grass and newly blooming roses floated in through the screens. Unmistakably, it was summer.

“You’ve got a summer job,” she whispered, “a real live summer job.”

She picked up the bottle of glass cleaner and a rag and began cleaning the mirror. Her Saturday morning routine had been set in stone for years: bedroom, bathroom, dining room, front hall, dishes. Always in that order. Within each room, the various chores were also ordered. Remove stale sheets or towels first. Then work from the top of the room down: walls, windows and sills, mirrors, furniture, baseboards, floor. Finally, make the bed with fresh sheets or hang fresh towels. Her arm went round and round across the smooth glass surface, the cloth buffing away imagined smudges. How many mirrors would there be in a rectory?

When I was your age, my dear, I could work rings around anyone. My father taught me the meaning of hard work early, by golly, and it’s never hurt me one single bit.

How her mother loved the idea of work. Especially if it was hard physical work where you had to bend over or reach up to lift or pull heavy things; where you had to apply force and scrub hard; anything that made you huff and puff and tired you out and gave you rough red hands at the end of the day. That was work, by golly. The backbone of character.

Cathy sprayed the mirror and began buffing it again. At least it had to be better than working for nuns. Priests were a lot more easygoing than nuns. Father McCoy flaring his nostrils like a horse, raising his eyebrows practically up into his hair to get a laugh. She’d never known a nun to make faces. Sister Anne Rochelle sometimes laughed at her own feeble little witticisms, but generally nuns didn’t clown around. And was there a priest anywhere who could come even close to Sister Lumina in sourness? Father Lauzon was very businesslike, perhaps impatient, but she had never sensed cruelty in him.

The vacuum cleaner stopped and the house fell silent. The skin on the back of Cathy’s neck contracted. How long had she been cleaning the mirror? Panicked, she put down her cloth and pulled open a dresser drawer. She would tell her mother that she was taking a moment to go through each drawer, refolding everything neatly.

The vacuum started up again, sucking, whining, thumping into the baseboards. At least while it was moving she knew where her mother was. She picked up another duster and the can of furniture polish. How much furniture would there be in a rectory? What would it be like? White French provincial, like this?

“In a guy’s room? What are you thinking?”

“Well, there are rooms other than bedrooms.”

“Yeah, at Marie Antoinette’s house.”

“She retired to a hat box, didn’t she?”

“Oh! Excellent.”

Cathy smiled as she sprayed a lemon-scented mist of polish over the surface of her dresser.

“I’m sure if the place is old, it will be all dark. That’d be better. See this? I can hardly tell where I’ve been. It’s better when the wood’s dark and you can just cut a path through the polish like plowing through snow.”

“As you wish.”

Working through her morning tasks, digging into crevices, rubbing vigorously, pulling things taut, her mother’s endless opinions flowed through her mind. Only dirty filthy pigs slept for more than one week in the same sheets; this wasn’t a museum, with spider webs allowed to grow to the size of hammocks in every corner; the French were lazy, which is why they chose white for all their furniture. They thought it didn’t show the dust. But they didn’t fool her, by Jesus. At least not anymore. It was just too bad she hadn’t seen through them before furnishing Cathy’s room with the darned stuff. But she wouldn’t be fooled again, no siree.

Because of her injuries, progress was slow, which was frustrating because Cathy wanted to finish up quickly and go over to Janet’s.

Guess what? I’ve got a job.

And she couldn’t keep her mind on her work. Her thoughts turned repeatedly to Father Lauzon. Although he had been the pastor at her church, St. Mary, Star of the Sea, for six or seven years before this latest transfer to St. Alphonsis, she really only knew him to see him and say a shy hello. As far as she knew, he never bothered much with parish kids. He had a distinctly un-priestly air about him. To her, he seemed more like a businessman than a priest. Tall and deep-voiced, hands nearly always shoved deep into his pockets, playing with loose change, he was friendly and aloof at the same time. On Sundays, after mass, he always came out into the church parking lot. You could hear him talking to everybody in his big booming voice. Cathy’d heard him joking with men parishioners, asking when he could get a game in at their golf club. She’d even seen him pull a golf bag out of the trunk of his car, so she knew he wasn’t just making conversation. And he whistled and sang all the time. Snippets of tunes from the radio. She couldn’t imagine him looking over her shoulder and fussing over details of housecleaning, investigating her work and raising his voice if he found a spot of dust somewhere or a wrinkle in a bedspread. He certainly didn’t look as if he’d care whether a rag was wrung out properly or not. In fact, Cathy was certain he wouldn’t even realize that some people considered that there was a right way and a wrong way to do such a thing.

As she finished up in her room, the last thing she did was adjust the angle of the slats in her blind to let in as much light as possible. Her mother liked lots of light in a room, except when she was brooding behind one of her closed doors.

She was expected to scour the bathroom from ceiling to floor, ensuring that all its shiny surfaces—mirror, white tile, white porcelain fixtures, silver chrome taps, faucets, and cupboard handles—all sparkled. She even had to bring the step ladder in from the garage and take down the round glass ceiling light cover and wash it so that when her mother turned on the light and looked up, she saw only light and not the little dark specks of dead insect bodies. Finally, she had to replace all the towels and facecloths and the bath mat, making sure they all hung perfectly folded from their correct rack.

Then came the dining room, dusting and polishing all the dark wood furniture and washing all the little square windows in the French doors. Finally, she had to wash and rinse the floor in the front foyer, put two coats of paste wax on it, and then buff it to a gleaming shine, first with the brushes on the electric floor polisher and finally with the lambs’ wool pads.

Her well-trained hands worked independently while her thoughts wandered, wondering about St. Alphonsis. She pictured herself answering a beautiful heavy dark door, placing a hat on a coat rack, and leading a visitor inside, settling him in a comfortable parlour before she went to knock softly on a study door and say, “Father, you have a visitor. Shall I make tea?”

Finally, at two o’clock that afternoon, having made sure that all the drapes and curtains in all the rooms of the house were wide open to the bright afternoon light, having checked that not a dish was out of place in the kitchen, and having changed her clothes and combed her hair, she was free. The last thing to do was to hunt through the lemon-, pine-, and vinegar-scented rooms for her mother. Cathy liked the sharp, tangy air. Along with the orderly appearance of the rooms, it was palpable evidence of all her hard work.

She knew to be diligent in her search. Sometimes you could miss Adele because she sat so silently, hidden in a corner of a room, sunk into a chair, staring at the carpet in front of her feet, with a cold cup of tea in her lap. This time, though, Cathy spied her through the dining room doors, sitting outside on the swing, with her head thrown back, her eyes closed, and the garden hose held tightly in her right hand. As the swing rocked gently back and forth, the water from the hose splashed across the trunk of the nearby hawthorn tree, tracked across the grass, spilled onto the soil beneath a lilac bush that her mother had recently transplanted, and then reversed its path. Cathy cautiously called out through the screen that she was going to Janet’s. She knew enough to pause, looking towards her mother, just in case Adele was watching her through narrowed slits. There might be one more task that she wanted completed. But this time, her mother did not respond, and so Cathy quickly and quietly left the house by the laundry room door.

The Saturday-morning lawn mowers had fallen silent, and the smell of fresh-cut grass had drifted away. Now the hot afternoon air was scented with petunias. Oppressed by the sun, people had abandoned the street to their automatic sprinklers, which were busy ffutt-ffutt-ffutting arcs of water across the front lawns. Cathy stepped off the end of her driveway onto the gravel shoulder of the road, listening to the playful sounds made by the shooting water. Ffutt ... ffutt ... ffutt ... ffutt ...went Mrs. Munro’s sprinkler onto her beds of pansies and then chucka-chucka-chucka-chucka- chucka-chucka-chuck as it mechanically jerked away in another direction. Quich ... quich ... quich ... said Mr. Grant’s sprinkler.

“Kinda like one big conversation out here, isn’ t it?”

Angela had fallen into step beside Cathy. She could have walked right out of a flowerbed in her hot pink silk top, bright green silk pedal pushers, and yellow sandals.

“Just goes to show you never know how many parallel worlds exist right beside yours, you know?”

Cathy was staring straight ahead to the end of the street. Angela followed her gaze.

“Ah! Tar bubble time.”

Cathy smiled, her mind flooding with the memory of how, years ago, on a hot day like today, with the sun beating down so hard that her black hair felt almost on fire to the touch, and the heat waves rising from the scorching asphalt, the tar bubbles would always be up. Good big ones, ready for pushing down. And they belonged to her and Isabel Labelle.

She began to run towards the end of the street, pulled by memory back into the summers of her childhood. The crown of the road was scarred with cracks that had been filled in with tar. The tar was melting and bubbles were there now rising up slowly in the broiling heat, tiny reflections of the sun riding on their glossy thinning surfaces.

“This the place?” Angela asked, arriving at her side.

“Right here.”

“How many on a team?”

“Doesn’t matter. Just the same number on each side.”

“Remind me of the rules?”

“You pair off your bubbles and just watch them grow. If yours gets to be the biggest, you get a point. Unless it bursts. Then you lose it and your team gets smaller. So that’s why you have to decide whether you’re going to push it down before it bursts so you can keep it. But if you push it down too soon, and the other team’s bubble gets bigger and doesn’t burst, they get the point.”

“Hmph!”

“Isabel and I used to spend whole afternoons lying here,” Cathy said, her hand drifting up to caress the side of her face, “with our cheeks on the road.”

“Yikes. A hot asphalt facial.”

“You can’t see the height of the bubbles unless you’re right down there beside them.”

“Wanna have a game?”

“Naw. It has to be Isabel.”

“Whatever happened to her?”

“Don’t know. Moved away.”

“You sure?”

“Yes. Years ago.”

“No, I mean them. Look at them. They’re just waiting for you.”

“Well, they’ll have to wait forever, now.”

“You taking the shortcut to Janet’s?”

“Uh-huh.”

“That stinky dark little cave?”

“It’s not a cave, it’s just the underpass.”

“I think there are rats under there.”

“You sound like all the mothers on the street from years ago. They told us that just so we wouldn’t play down there. I’ve never seen a rat.”

“Just the same...”

“See you.”

Standing alone in the middle of the deserted street, Cathy looked down at the tar bubbles. It felt like a lifetime ago that she and Isabel had played there.

There was a ditch at the end of the road with a little dirt path worn into the grass at the water’s edge. Cathy left the pavement and headed through the little buffer of field and then down over the edge of the slope. Beneath her shoes, the coarse crunch of the gravel shoulder changed to the soft crackling of weeds and grass. Flowered walls rose up on either side of her. The slopes were covered in purple and white clover, brilliant yellow dandelions, pale pink and white bindweed blossoms, and tiny yellow hop flowers. In amongst the flower heads an army of insects bobbed and hovered, hunting for the things that sustained them. They brushed past her hair, intent upon their survival. On the opposite side of the water, a red-winged blackbird trilled from atop a stalk of last season’s thistle.

When she reached the path the sound of trickling water blotted out the rasping, rustling vegetation. She paused to watch the stream for a moment, wondering how much water had flowed past, day and night, in the years since she had played here. This was one of life’s mystery questions. There would be an exact number, but it would be unknowable.

The path threaded beneath the concrete underpass. As she stepped into the cool darkness of the cavern-like space, the sound of the moving water intensified. Her eyes adjusted to the dark and her skin rippled with goosebumps as she pressed close to the damp cement wall. It stank of mould and sulphur under there and was cool enough to chill meat. There probably could be rats.

Emerging into the sunlight again a moment later, the sound of running water dropped, replaced by more rustling and bird-song. She picked her way carefully across the water, stepping on protruding rocks and discarded half-broken cement blocks, refuse from past bridge-building exploits of excited little neigh-bourhood boys. Once on the other side, she followed another path for several more minutes until just before encountering another road crossing. Then she trudged up the angled slope, leaving the flowers and the sounds behind her, and set her foot upon the arbour-covered delight that was Whitehall Boulevard.

Janet St. Amand had been Cathy’s best friend ever since the day, eight years ago, that Sister Gertrude brought her by the hand to the door of the Grade 2 classroom in the middle of the morning and asked Sister Joseph to make room for a new pupil. Sister Joseph took the delicate little blonde girl by the hand and sat her down in the empty desk right across the aisle from Cathy.

The newcomer obviously didn’t own a school uniform yet. She was wearing a dress with bright coloured tulips all over it; Cathy remembered this because a tulip was one of the few flowers that she was able to identify at that age. When Sister Joseph turned her attention back to the examples of addition and subtraction on the blackboard, Cathy remained staring at the brilliant colours, unable to tear her eyes away.

Janet’s house was midway down the boulevard, a lovely old English manor with a dramatic sloping roof above the front door and lead-paned diamond-shaped windows that twinkled in the sunlight like bits of treasure hidden among the dark leafy ivy that covered the brown brick exterior.

Just as her hand was in the air, about to knock on the screen door, Eva, with her shiny blonde hair caught up in a ponytail and tied with a bright blue scarf, came around the side of the house with Whisky, a blonde cocker spaniel, at her heels. She had been gardening and her hands were caked with mud.

“Well, hi there, sweetie. Long time no see. How come you’ve been such a stranger? Your timing is perfect, though. Now you can get the door for me. How many times do I have to tell you not to knock?”

She slipped past Cathy, followed by the dog, and paused to kick off her moccasins on the landing inside, calling up the stairwell to Janet that her best friend in the world was here.

The three of them converged in the kitchen a moment later, Eva going immediately to the sink to wash up, Cathy choosing to lean on a cupboard near the door, and Janet making a speedy arrival from upstairs right into the middle of the room, courtesy of a long skid in her stockinged feet. She narrowed her eyes at Cathy immediately.

“What happened to your face?”

“I know. I know. Nice mess, huh?”

“What’s the problem, sweetie?”

Eva turned around to see what Janet was talking about.

“I’m so clumsy. My mother says I can’t stand on my feet for more than ten minutes at a time.”

Eva shook her wet hands in the sink and then took Cathy by the wrist and pulled her into the light in front of the window, sweeping Cathy’s dangling hair out of the way.

“Ew, honey, that looks really sore. I didn’t notice that at the door. How did you do that?”

“Oh, it’s a really dumb story. My father was washing the car in the garage yesterday and there were soapsuds and water all over the floor and I was in a hurry to get to the bathroom. I shouldn’t have been running, but I was desperate, and I slipped just when I got to the door. I hit the doorknob on the way down.”

“Oh, you poor thing. Did you put ice on it?”

“Yeah, a bit.”

“Well it sure looks like it could use some more. Here, sit down.”

Eva dried her hands on a tea towel and took a tray of ice cubes out of the freezer. A moment later she swept Cathy’s hair gently out of the way again and lightly pressed an ice bag to the swollen cheekbone.

“You should be more careful, sweetie. You could have put out an eye or something. It’s hard to tell if you’re gonna get a shiner or not. I don’t see any blood under the skin near your eye. There’s just a bit over the bump. It looks like there’s been a very little bit of bleeding there. That’s an awfully hard swelling though. You must have hit the bone. Did you hurt anything else?”

“No.”

“Did your mother watch you for a concussion? You’re not supposed to go to sleep right away after a bump on the head, you know. If it’s a really bad bump and you get sleepy right after, then it usually means that you’ve got a concussion.”

“Oh, it wasn’t really that hard. It just looks worse than it is. I don’t even know what a concussion is, really.”

“A bruised brain.”

“So why can’t you go to sleep if you have one?”

“I’m not exactly sure, but any drowsiness after a bump on the head can indicate that you’ve actually bruised the brain, and I think if it’s serious you can actually slip into a coma.”

“Well, I guess I don’t have one because I woke up same as usual this morning.”

“What did you do to this?”

Janet was pointing to the adhesive tape on one of Cathy’s fingers.

“Oh, that’s not related. I’m just trying to save a broken nail, that’s all.”

She thrust her hand out in front of her, turning it this way and that, examining the white taped finger, surreptitiously widening her eyes to the evaporating air.

Janet poked her nose into a brown paper grocery bag standing on the table. She pulled out a chunky blue box of tampons.

“Yea. More corks. Huge box! They on sale or something?”

“Well at the rate you use them I’m beginning to wonder if you’re smoking them or something.”

“Ew. Yuck, Mom.”

“Well. They sure don’t last long with you around.”

“Well, you’re just lucky I’m not like Lucy De Finca then.”

“Who?”

“Sandra De Finca’s little sister. You don’t know her. She’s in Grade 8. She has to use two at a time.”

“Two at a time? How can you do that?”

“Put the first one in really far and then hold onto the string so you don’t lose it and put a second one in. Sandra told me it’s the only way Lucy can use them without getting a leak.”

“Hm. I never thought of doing that. It sounds like a good idea. Sure beats using those manhole covers. Poor kid, flowing so heavily at her age.”

“Manhole covers?”

Cathy looked at Eva with even more wide-open eyes and started to giggle uncontrollably. Eva smiled.

“Well, what else would you call them? They make you waddle around with your legs two blocks apart, you can’t wear anything tight, they bunch up in the hot weather, it’s like sitting down on a stack of damp books, they’re hot, they smell awful, you can’t swim. Who the heck needs to live in the Dark Ages like that? You couldn’t pay me to use pads ever again. You girls are really lucky that tampons were invented so you never have to go through that.”

“And how.”

Janet lifted a package of fig cookies out of the grocery bag and tore open the cellophane.

“Here,” she said to Cathy, pushing the open end of the package towards her. “Have some. I’ll get some milk.”

“So, Cathy, besides beating up on yourself and nearly putting out an eye, what’s new?”

Eva was bent over a vegetable crisper in the fridge, her voice coming out from behind the opened door.

“Yeah,” said Janet. “I didn’t see you at all last weekend. What’s up?”

“Well, I’ve got a summer job.”

“Really? How neat. Where?”

“Well, my mother got it for me. It’s out at St. Alphonsis Church. You know, where Father Lauzon got transferred to?”

Eva had now closed the fridge and was rooting through the cutlery drawer looking for a knife to chop an onion.

“That’s way out in the east end, isn’t it?”

“Yeah.”

“What’s the job?”

“I’m going to be a housekeeper.”

“What?”

“I know. Funny, eh? Me, a housekeeper. But the one that used to be out there died and they can’t find anybody to replace her, so I’m it for the summer.”

“You’re kidding. What do you have to do?” Janet asked.

“My mother said it’s nothing out of the ordinary. Just dishes and dusting and making beds and getting their meals.”

“Just! It sounds like a lot of work to me.”

Eva finished chopping, leaving a mound of onion bits on the breadboard, and turned her attention to breaking apart ground beef with a wooden spoon in a large bowl.

“How many priests?”

“Three.”

“You have to cook meals and pick up after three men? Boy, I don’t envy you that. How many days a week?”

“Monday to Friday. They have to fend for themselves on the weekends, I guess.”

“Well,” said Janet, pulling half a dozen cookies out of the package and putting them on a plate, “I hope they give you a vacation so you can come up to the cottage again this summer.”

“Oh, I’m sure you won’t be there that long, sweetie,” Eva said, brushing onion off the board into the bowl with the meat. “That’s a full-time job getting all those meals for three grown men and running a household. They’re gonna have to find a permanent replacement fairly soon, I would think. I know you’d like the money and everything, but you’re still just a young girl. You have the whole rest of your life to work. Besides which, keeping up with your own housework is boring enough without having to do someone else’s. I don’t know how Crystal comes here every week and puts up with us and this house. And she’s been a cleaning lady for years. She sure does a terrific job, though. I couldn’t survive without her. I’m sure you’ll do a great job for them.”

“As long as I don’t burn everything to a crisp on the first day.”

“Make sandwiches,” said Janet. “What can go wrong?”

“Actually, before you go home, sweetie, I’ll give you a copy of this recipe that I’m making. It’s for Scandinavian meatballs. It’s really easy. You just make these tiny meatballs here, like I’m doing, and then there’s a nice rich gravy that goes with them that’s also really easy to make. You serve everything over rice and you don’t need another thing to go with it. The priests will love it.”

“I’ve never made rice before.”

“Oh, that’s easy. You just boil water, add the rice, turn the heat down really low, and wait. That’s all there is, really, to making rice. It sort of makes itself. Even Whisky could do that if she had to, couldn’t you, sweetie.”

Just at that moment, with her stubby tail stump vibrating rapidly, the dog shot out from under the table to retrieve a scrap of onion that had fallen off the breadboard onto the floor.

Later, when Cathy left, with the recipe for Scandinavian meat-balls folded and stashed in her pocket, Eva called out to her from the door, “Get your mother to put some ice on that cheek for you. And cold cucumber slices, too. They’ll help. Get her to slice them really thin.”

Cathy paused on the path down beside the steadily trickling water and brought the piece of pale yellow writing paper out of her pocket. The golden late afternoon light sloped over her shoulder. Eva’s handwriting was lovely, curved and tidy, pretty to look at. Cathy gazed at the cheerful scrolls and loops and then gently pressed them against her swollen cheek. The paper had picked up the scent of Eva’s hand cream. She stood like that for a moment, eyes closed, with Eva’s handwriting and the warm sun touching her face. Get your mother to put some ice on that cheek for you. And cold cucumber slices, too. They’ll help. Get her to slice them really thin.