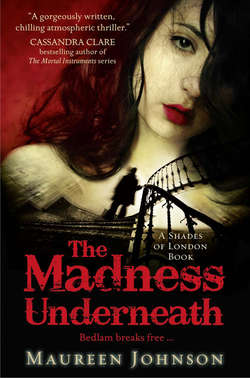

Читать книгу The Madness Underneath - Maureen Johnson - Страница 9

Оглавление

HIS DESTROYING-THE-DEAD-WITH-A-SINGLE-TOUCH thing was even more recent than the seeing-the-dead thing. It had happened once before, the day I left Wexford. I’d found a strange woman in the downstairs bathroom where I’d been stabbed. She too had looked frightened, and I’d reached out, and she too had exploded into nothingness. I’d tried to tell myself that this had been a fluke, something to do with the room itself. The bathroom was where the Ripper had cornered me. The bathroom was where the terminus had exploded. I’d convinced myself that the room did it.

But no. It was me.

I walked home, an entirely uphill walk in every way, feeling queasy and shaky. Once there, I went to the “conservatory,” which was really just a glassed-in porch. I sat with my head resting on my knees and replayed the scene again and again in my head. The inevitable rain came and tapped on the roof, rolling down the panes of glass.

I’d tried to make a new friend, and I had blown him up.

I’d been told to keep quiet, and I had. But it wasn’t going to work anymore. I needed Stephen, Callum, and Boo again. I needed them to know what was going on with me. I had made a few efforts to find them in the last week. Nothing serious—I’d just tried to find profiles on social networking sites. No matches. This much I expected.

Today I was going to try a bit harder. I Googled each of their names. I found one set of links that were definitely about Callum. Callum had mentioned that he was good at football. What he didn’t say was that he had been a member of the Arsenal Under-16s, a premier-level junior club. He’d been in training to become a professional footballer. And all of that ended one day when he was fifteen, when a malicious ghost let a live wire drop into the puddle Callum was stepping through. He survived the electrocution and recovered, but something in him was never the same. Whether it was physical or psychological, who knew, but he couldn’t play football anymore. The magic was gone. Callum hated ghosts. He wanted them to burn.

In terms of contact information, though, there was nothing.

I moved on to Boo, Bhuvana Chodhari. Boo had been sent into Wexford as my roommate after I saw the Ripper. It was her first job with the squad. There were a lot of Chodharis in London, and even quite a few Bhuvana Chodharis. I knew Boo had been in a serious car accident, but I found nothing about it. Nothing about Boo at all, really. That surprised me. Of the three of them, I expected her to pop up somewhere. But I guess once you joined the squad, your Facebook days were over.

I searched for Stephen last. In terms of his past, I knew very little. I think he said once he was from Kent, but Kent was a big place. He went to Eton. He had been on the rowing team while he was there. I started with that, and managed to come up with one photo of a rowing team in which I could clearly see him in the back. He was one of the tallest, with dark hair and eyes fixed at the camera. He was one of the not-smiling ones. In fact, he was the least-smiling person in the photo. Like everyone else, he had his arms folded over his chest, but he seemed to mean it.

But again, there was nothing in terms of how to make contact.

I stared at the photo of Stephen for a long time, then at the ceiling of the conservatory, which was thick with condensation and fat drops of water. I knew that Stephen and Callum shared a flat on a small street in London called Goodwin’s Court. I’d been there. I had never, however, looked at the building number. The few times I’d been there, I was following someone to the door, usually in a state of distress.

I pulled up a map and some images of the street. The trouble with Goodwin’s Court was that it was very picturesque, and very small, and all of it looked more or less the same. The houses were all quite dark, with dark brick and black trim, so it was hard to see numbers. I found one pretty grainy picture that I thought was probably their house, but I couldn’t see the number.

My phone rang. It was Jerome. He often called me on his break between classes. Jerome had been what I suppose I could call my “make-out buddy” at Wexford. But since I’d been gone, we had become something much more. I still couldn’t talk to him the way I needed to talk to someone, but it was nice that I had someone in theory. An imaginary boyfriend I never saw. We were planning to see each other over the Christmas break in a few weeks, probably only for a day, but still. It was something.

“Hey, disgusting,” he said.

Jerome and I had developed a code for expressing whatever it was we felt for each other. Instead of saying “I like you” or whatever mush expresses that sentiment, we had started saying mildly insulting things. Our entire correspondence was a string of heartfelt insults.

“What’s wrong?”

“Nothing,” I said quickly. “Nothing.”

“You sound funny.”

“You look funny,” I replied.

I could hear Wexford noises in the background. Not that Wexford noises were so particular. It was just noise. People. Voices. Guys’ voices.

He was talking quickly, telling me a story about some guy in his building who’d been busted for claiming to have an interview at a university, but actually he went off to see his girlfriend in Spain, and how someone had ratted him out to Jerome, and Jerome had the unwelcome task of reporting him. Or something.

I was only half listening. I rubbed at my legs and stared at the images of Goodwin’s Court. I hadn’t shaved in three weeks, so that was quite a situation I had going. For the first few days, I hadn’t been able to bend over completely or get the injured area wet, so I couldn’t shave. The hairs sprouted, and they were kind of cute. So I just let them go to see what would happen, and what had happened was that I had a fine web of delicate hair all over my legs that I could ruffle while I watched television, like some people absently pet their cats. I was my very own fuzzy pet.

The grainy picture told me nothing.

“Hello?” Jerome said.

“I’m listening,” I lied. I guess the story had finished.

“I have to go,” he said. “You’re disgusting. I want you to know that.”

“I heard they named a mold after you,” I replied. “Poor mold.”

“Vile.”

“Gross.”

After I hung up, I pulled the computer closer to stare at the image. I moved the view up and down the row of tiny, dark houses with their expensive gaslights and security system warning signs. Up and down. And then I saw something. There was a tiny plaque on the outside of one of the houses, right above the buzzer. That plaque. I knew it. That was their building. There was some kind of a small company downstairs, a graphic designer or photographer or something like that. The print was impossible to make out in the photo, but it began with a Z. I knew that much. Zoomba, Zoo . . . Zo . . . something.

It was a start, enough to search the Internet. I tried every combination I could with Z and design and art and photography and graphic design. It took a while, but I eventually hit it. Zuoko. Zuoko Graphics. With a phone number. I pulled up the address in maps, and sure enough, it was the same building.

Now all I had to do was call and ask them . . . something. Get them to go upstairs. Leave a note. I would say it was an emergency and that they needed to call Rory, and I would leave my number. So simple, so clever.

So I called, and Zuoko Graphics answered. Well, some woman did. Not the entire agency.

“Hi,” I said. “I’m trying to reach someone else in this building. It’s kind of an emergency. Sorry to bug you. But there are some guys? Who live upstairs? From you?”

“Two guys, right?” the woman said. “About nineteen or twenty?”

“That’s them,” I said.

“They moved out, about a week and a half ago.”

“Oh . . .”

“You said it’s an emergency? Do you have another way of reaching them, or—”

“It’s okay,” I said. “Thanks.”

So that was that. I struck that off the list. They’d moved out. Because of me? Because I knew where they lived? Maybe they were really cleaning up their tracks so they could never be found again.

I heard someone come into the house. I quickly clicked on a link to BBC news and pretended to be deeply engrossed in world affairs. My mom came into the kitchen.

“We have chairs,” she said.

“I like it down here. It’s where I belong.”

“Doing some work?” she asked.

My parents weren’t stupid. They knew I hadn’t really been keeping up with school stuff, but they hadn’t been pressuring me. I was recovering. Everyone was very gentle with me. Soft voices. Food on demand. Command of the remote control. But there was just a little lilt of hope in her voice, and I hated to disappoint her.

“Yup,” I lied.

“I just got a call from Julia. She’s asking all of us to come in tomorrow for a group session. Is that all right with you?”

I ran my thumbs along the bottom edge of my computer. This wasn’t right. We didn’t do group sessions. Was this an intervention? It sounded like an intervention, at least like the ones I had seen on TV. They get your family and a psychologist, and they sit you in a room and tell you that the game is up, you have to change. Change or die. Except . . . I didn’t drink or do drugs, so I wasn’t sure what they could intervene about. You can’t stop someone from doing nothing all time.

I thought about the man again . . . my hand reaching out in greeting. Maybe the first greeting he’d had in years. The hand that wiped him from existence. Or something.

“Sure,” I said, slightly dazed. “Whatever.”

The next day at noon, the three of us waited by Julia’s door, staring down at the little smoke-detector-shaped noise-reduction devices that lined the hallway. That’s how you could tell a therapist was behind the door. One of these little privacy devices would spring up naturally, like a mushroom after a rainstorm.

“So,” Julia said, once we were all squeezed onto her sofa, “I want to talk to all of you about the progress we’ve made, and just a little bit about the process. Recovering from a trauma like this. There’s no one method that fits everyone. I want you to know, and I want you to hear this, Rory . . . I think Rory is very, very strong. I think she’s resilient and capable.”

It was supposed to make me feel good, but I burned . . . burned with anger or embarrassment or resentment. I felt my cheeks flush. This was the worst of it. Right now, this. I’d survived the stabbing. I’d survived all of the other, much crazier stuff. But now I was a victim. I might as well have had the word tattooed on my face. And victims get strange looks and psychologists. Victims have to sit between their parents while they’re told how “resilient” they are.

“In my opinion, I feel . . . very strongly . . . that Rory should be returned to Wexford.”

I seriously almost fell off the sofa.

“I’m sorry?” my mother said. “You think she should go back?”

“I realize what I’m saying may run counter to all your instincts,” Julia said, “but let me explain. When someone survives a violent assault, a measure of control is taken away. In therapy, we aim to give victims back their sense of control over their own lives. Rory’s been removed from her school, taken away from her friends, taken out of her routine, out of her academic life. I believe she needs to return. Her life belongs to her, and we can’t let her attacker take that away.”

My dad had a look in his eye that I’d once seen in a painting at the National Gallery. It was of a man who was facing down an angel that had just come crashing through his ceiling and was now glowing expectantly in the corner of the room. A surprised look.

“I say this with full understanding that the idea may be difficult for all of you,” she continued, mostly to my parents. “If you decide against this, that’s absolutely fine. But I feel the need to tell you this . . . Rory and I have done quite a lot of work in our sessions. I’m not saying we’ve done all we can do. I’m saying the next logical step is to get her back into a normal routine.”

She was lying. Julia, right now, was lying. And she was looking right at me, as if challenging me to contradict her. We both knew perfectly well that I’d told her nothing at all. Why the hell would Julia lie? Had I said things without even realizing it?

“She can have a normal routine here,” my mom said.

“It’s not her normal routine. It’s a new routine based around the attack. Right now, keeping her away from the learning environment is punitive. I’m not talking about sending Rory out to live in a wild and dangerous environment—this is a structured one, with everything in place to allow her to resume her life.”

“An environment where she was stabbed,” my dad said.

“Very true. But that particular case was a true anomaly. You need to separate your fears from the actual risk involved. What happened will not be repeated. The attacker is deceased.”

Their conversation became a low buzzing noise, like the background sound that’s supposed to run across the universe. Of course I couldn’t go back. My parents would never agree to it. It had taken me a week to convince them I could walk down the hill by myself. They were never going to send me back to school, in London, to the very place I’d been stabbed. Julia might as well have asked me, “Rory, do you want to go live in the sky? On a Pegasus?” It was not going to happen.

As ridiculous as this all was, if there is one thing that could sway my parents, it was a professional opinion. An expert witness. They both dealt with them all the time, and they knew how to take that knowledge and advice. Julia was a professional, and she said this was what I needed. They were still listening.

“I’ve been in touch with them,” she went on. “There are new security measures in place. They have a new system that apparently cost a half a million pounds.”

“They should have had that before,” my dad said.

“It’s best to think forward,” Julia said gently, “not backward. The system includes biometric entry pads and forty new CCTV cameras feeding into a constantly monitored station. Curfew hours have been changed. And the police now include Wexford on a patrol, simply because of all of the publicity. The reality is that it is probably the most secure environment she could be in right now. The school term is only going to last about two more weeks. This short period would allow her to reintegrate herself. It’s an excellent trial run to get Rory back into a more normal routine.”

Oh, the silence in that room. The silence of a thousand silences. I could hear that stupid clock ticking away.

“Do you really feel ready?” my mom asked me. “Don’t let anyone talk you into feeling like you’re ready.”

It wasn’t phrased as a question—I think it was more of an invitation. They wanted me to say I wasn’t ready, and we would just go on like this, safe and secure and static.

This was happening. They were saying yes. Yes, I could go back. No, they didn’t want me to, and yes, it went against every instinct they had . . . and possibly against every instinct I had.