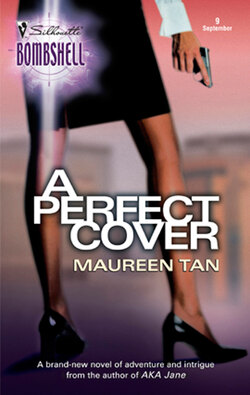

Читать книгу A Perfect Cover - Maureen Tan - Страница 10

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеI was sitting in darkness, waiting to be rescued. Or to die. As were we all. More than fifty of us, trapped inside the long, battered trailer of an eighteen-wheeler. Men and women, young and old. A few adolescent children. But no infants. Yet.

All around us were splintery shipping crates, large and small. They filled the trailer top to bottom and front to back, with just enough room left between the rows to conceal a human cargo. Shipping labels, stenciled in black paint, said the crates contained an assortment of machine parts destined for America. We, too, had been destined for America. But the truck that pulled us was long gone, its trailer and its cargo—human and machine—stationary. We were locked in and abandoned. And the heat was becoming unbearable.

Beside me, Rosa groaned—a deep, harsh sound with surprisingly little volume to it. I leaned in closer to her, my hand brushing the sleeve of her light cotton dress, then moving to find a thick braid, a soft cheek and, finally, her forehead. It was damp with perspiration. From the heat. And from her labor. I stroked Rosa’s hair back away from her face, murmured pleasant, soothing nonsense and tried to give comfort where none existed.

Rosa groaned and tensed again. My wristwatch was gone, stolen. But I had counted the seconds between her contractions, confirming what we both already knew. Soon, Rosa’s child would arrive. And I wished I could stop the inevitable.

I’d met Rosa weeks earlier. As the sun rose over the lush green of the jungle, a group of desperate and excited strangers had gathered on a hill, close enough to the Actuncan Cave to feel the cool, damp air flowing from its mouth. We had each paid a life’s savings to smugglers called polleros— chicken herders—for a few forged papers, the promise of a minimum-wage job and legal citizenship for any of our children born on U.S. soil.

“Me llamo Rosa Maria Martinez,” Rosa had said. “I go to America. To New York City.”

“I am Lupe Cordero,” I replied in Spanish that was touched by the distinctive accents of rural Guatemala. “From Chichicastenango. I am fifteen and go to live with my sister in Houston.”

Lies. All of it. My real name was Lacie Reed. I was twenty-seven, an American citizen, and I had no sister. But there was nothing about my appearance to make her doubt me. My hair was dark and curly, my skin unwrinkled and golden-brown, my almond-shaped eyes dark. And I was tiny—small-boned and just a breath over five feet tall. Like Rosa and the others, I was dressed to travel in nondescript clothing that would draw little attention.

This wasn’t the first time I’d lied for my Uncle Duran. I was Special Assistant to the Right Honorable Senator Duran Reed, a position that covered an amazing variety of activities. This time, it meant being part of an interagency task force that included Mexico’s National Immigration Institute and the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. The INS.

For two weeks we traveled together on foot, by car and by rickety open truck, making our way from Flores to Tapachula, Mexico. Then two days by freight train brought us to Veracruz. We spent that night in a warehouse, on a dirty concrete floor surrounded by fifty other exhausted refugees.

The United States government wanted these people stopped. These and many thousands like them. A flood of illegals from Central and South America passing through Mexico on their way to the U.S. But even as the government of Mexico cooperated with the U.S. to solve the problem, corrupt officials grew rich extorting the immigrants.

If organized traffickers were brought to justice, the danger for those who continued traveling along Mexico’s underground highway would be lessened. But that required the testimony of a reliable witness. And immigrants who cooperated with the authorities had a bad habit of disappearing or dying.

That was where my skills came in.

In the dim yellow light of a bare overhead bulb, in the layer of grime on the warehouse floor, I used the edge of a plastic cigarette lighter I found in a corner to draw the faces of two National Railway workers I had seen taking bribes that day. It didn’t matter if I used a pencil on a sketch pad, a piece of chalk on a blackboard or a stick on a smooth patch of ground. If I drew what I saw, I could remember it and reproduce it accurately. Always. Faces were easy. As were diagrams and numbers. More than that, the very process of drawing objects and people freed my intuition, enabling me to make connections that weren’t apparent when I merely observed a situation.

And so, that night, I added more descriptions to my mental catalog of incidents and faces. My sketches at journey’s end, along with my recollection of dates, locations and times, would enable both governments to identify and arrest traffickers. Then I would testify against them.

The sun was just rising when we loaded into the truck. We went willingly, ducking beneath an overhead door that had been raised only a few feet from the trailer floor, moving as quickly as we could into the shadowy interior. We squeezed through a maze of claustrophobic aisleways created by shipping crates, occasionally crouching low to avoid a load bar. When our progress through the trailer was briefly stalled by a large, slow-moving man from Honduras, I looked more closely at one of the bars. A ratcheting mechanism telescoped the tubular steel bar outward until it spanned the width of the trailer. Swivel rubber pads at each end wedged the bar tightly into place, creating a strong, temporary, horizontal barrier.

At the far end of the trailer was an open area large enough—barely—to accommodate all of us. Rosa and I settled down in a cramped corner as a pollero announced that the drive would be long and uncomfortable. But it would end in America. In Laredo, Texas. In the meantime, we could relieve ourselves in the buckets he’d placed inside the trailer for us. Then he closed the door with a thud and I heard a heavy lock drop into place. The truck lurched its way out of the freight yard and picked up speed on the roadway.

We were still moving when the narrow pinpoints of daylight coming through small scars in the trailer’s aluminum shell faded to darkness.

In the middle of the night, things went terribly wrong.

It started with sirens in the distance. As the sound came closer and caught up with us, conversation stopped inside the trailer.

“Uno. Dos. Tres.” Rosa counted under her breath as the sirens resolved themselves into at least three vehicles.

The truck slowed and the surface beneath the tires roughened. The floor beneath us sloped slightly to one side as the driver pulled the rig onto the shoulder of the road. But he kept the truck moving.

The sirens blazed past. The red lights of emergency vehicles glanced off the trailer, throwing shattered fragments of light into the interior. Then the light was gone. And the sirens were lost in the distance.

But the driver must have panicked. The truck pulled back onto the highway, continued along at high speed, then abruptly braked and downshifted to make a right turn. More time passed and the road deteriorated. The movement of the trailer became increasingly violent. We were thrown like rag dolls, bouncing against each other and into the unyielding shipping crates.

Then, abruptly, the terrifying ride stopped.

For a moment, except for the sound of the engine, there was silence. Then male and female voices erupted, shouting in Spanish, cursing the driver in the vulgar colloquialisms of Mexico and Guatemala and Honduras and El Salvador. We threatened him, demanding that he open the trailer door and let us out now. But the driver didn’t respond. Instead we felt the jolt as he freed the truck from the trailer. Then he drove away, abandoning us to the desert heat.

Despite the exterior lock, a dozen sets of bare fingers and straining backs and shoulders tried to pull the trailer door upward. The heavier men and a few of the women threw their shoulders against the door, trying to shift it outward. We climbed up the stacked crates, grasped the overhead track for the door and tried to yank it from the brackets that mounted it to the ceiling.

We were still working to escape when the pale beginning of a new day gradually found its way in through the tiny holes in the trailer wall. The heat inside the trailer grew worse. As each escape attempt was revealed as futile, activity inside the trailer slowed. An hour past dawn and those inside the trailer were quiet. Deathly quiet.

Rosa cried out again.

Her contractions were now coming in waves, one after another, barely giving her time to rest in between. For the first time since her labor began, she began crying. Quiet, hopeless weeping. Heart-wrenching, inconsolable weeping.

“Never give up, little one,” I murmured.

Only after I had spoken did I realize that I’d said the words in Vietnamese, repeating them exactly as I had first heard them. Rosa was too preoccupied to notice, but the words brought back memory, still vivid though two decades had passed.

I was eight when Grandma Qwan put me on a fishing boat crowded with people fleeing Vietnam. The men she’d paid had assured her that I would be safe. And perhaps they’d believed that. But we were intercepted midvoyage by Thai pirates. From my hiding place beneath a pile of rotting nets, I listened to the screams as they murdered the men, raped the women and stole everything of value.

Fourteen of us were left alive—cast adrift on a ruined boat without food or water. Thirteen women and one scrawny, mixed-race orphan who reeked of fish guts and filth. Days passed. One by one, the others died. Some of thirst and exposure. Some quietly, hopelessly, casting themselves into the sea. Until just one young woman and I remained. Though I was just a child, I had seen enough death to know that she would not live much longer.

That night she had held me close.

“Never give up, little one,” she had whispered in Vietnamese, as if she were telling me a precious secret.

When I awoke, she was gone. And I was alone.

I did not despair. I did not give up.

I had come too far to die today.

I stopped thinking about the imminent arrival of Rosa’s child. Using an edge of the cigarette lighter against the vertical surface of a nearby crate, I imagined that I was drawing with a nicely sharpened charcoal pencil on paper torn from an expensive vellum pad. I drew the exterior of the trailer, its only door solidly locked, and surrounded it with desert. A blazing sun hung in the sky. Mentally, I set that drawing aside. Then I drew the interior of the trailer.

I began with a rectangle with six solid walls—back and front, sides, ceiling and floor. I sketched the details of a door that pulled upward to open, that rode on tracks mounted parallel to the ceiling. Between the tracks and the ceiling there was at least a foot of space. I added crates. And refugees. And load bars that ratcheted into place…

The load bars could be moved!

I stood and began dragging at one of the horizontal bars as I described my plan to the others. Within moments, I had help. We freed the bar, set it on its end and ratcheted it upward until it pressed against one of the tracks from which the trailer door was suspended. Then the big, slow-moving man from Honduras, who was the strongest among us, continued working the stiff ratchet. He lengthened the load bar one inch at a time until there was so much pressure against the track that it buckled and bent.

Though the door remained on its track, it sagged at a top corner, bringing in a triangle of bright sunlight and a hot desert breeze that was fresher and cooler than the stale air inside the trailer. The space between the door and its frame wasn’t very large. Even the weight and strength of the man from Honduras failed to make it larger. But the gap was enough that a very small, athletic woman from Vietnam could squeeze herself through.

I pushed myself through headfirst and on my back. Head and shoulders escaped the trailer and above me I saw the brilliant blue Texas sky. Cloudless and beautiful. Breathtaking. But the thrilling moment of rebirth was immediately quashed by more practical concerns.

Grabbing finger and handholds wherever I could find them, I hauled myself upward until my entire body was free of the trailer. Then I hung for a moment, catching my breath, taking advantage of the trailer’s height to look off into the distance. As far as I could see, there was nothing but clumps of scrub, spiny cactus and an occasional thorny tree. And lots of rocks. The largest of which I tried not to land on when I pushed away from the trailer and dropped to the desert floor.

The landing was inelegant, but relatively painless. I picked myself up off a patch of dusty earth, spent a moment prying a large dry thorn from the palm of my right hand and dusted the back of my pants. Then, using a solid-looking rock, I tried to dislodge the padlock that locked the trailer door down. Spurred by cries of encouragement coming from within the trailer, I bashed and pounded at the lock until my hands were bloody, until the rock split in two.

Then, though no one could see me, I shook my head. Beating at the lock was wasting time and eating away at my remaining energy. Adrenaline helped, but it was only a temporary cure for dehydration and heat exhaustion.

“Take care of Rosa,” I shouted in Spanish. “I will go find help. And I will come back. I swear.”

Then I turned my back on the trailer, focusing on a single goal. I had to find help. For everyone. I began following the truck’s tire tracks. I wanted to hurry, to run, to push myself to my limits. Instead, I walked. Slowly, steadily, concentrating on my breathing.

I was already tired and thirsty. It didn’t take long before even the ruthless beauty of the desert held no appeal. Thoughts of how I would go about capturing its arid vistas with pen and ink faded. I began cursing the cloudless blue sky, the thorns that pierced my clothing and my skin, the rocks and sand that filled my shoes, and the relentless late-morning sun. My head throbbed in rhythm with every step, with every painful breath.

My attention drifted, back to the trailer, back to Rosa, back to our travels through Mexico and Guatemala. I saw myself walking in the streets of Flores and Veracruz and Tapachula. I stumbled on a rock and fell hard onto my hands and knees. A dry black branch tore a jagged furrow in my leg. Pain brought concentration back with a snap. Ignoring the warm trickle of blood down my left calf, I stood. And made a horrifying discovery.

I had wandered away from the tire tracks.

I tried not to panic, tried not to think of dozens dying because I had gotten lost. I took a deep breath, then another, and carefully reoriented myself. The tracks had been heading north and I had followed them, keeping the rising sun on my right. Now I was facing directly into the sun. I turned slowly, looking for evidence that a truck had recently passed that way. Several dozen yards to my left, I spotted a crushed cactus and a brittle, skeletal tree whose spindly limbs were smashed on one side. I walked in that direction and rediscovered the tracks.

I walked on.

I am in Texas, I repeated to myself. In Texas. Near Laredo. And I must find help. I concentrated on the pattern of tires in the dust. On the details left by the tread. On the texture of the plants crushed by the truck’s passing that way not once, but twice. On the tiny brown lizards that skittered frantically across my path. On insects so small that the track’s grainy texture shaded them.

I walked on.

The tire tracks led to the barest hint of a road. I followed it, head bent, eyes downcast, focused only on the scars that passing tires had laid on the desert floor. I traced each scar with an imaginary stylus, wove each detail into an imaginary length of rope stretching between me and the main highway, between me and the help I needed.

I walked on.

Soon nothing mattered but the heat. The dreadful, pounding heat. And the imaginary rope. I held on to it with my mind, with all the strength that remained in me, watching closely as it gradually twisted, turned and changed. It became a fishing net, worn but still strong, tossed into the sea by the sinewy brown hands of Thai fishermen. Thrown to a child who drifted, helpless and alone, in a battered boat on the South China Sea. Pulled on board by hands that eagerly pressed a tin cup of water to a child’s parched lips.

I walked on.

Suddenly there was a blaring horn and squealing brakes.

America! I thought as I heard a woman shouting at me in English. I’ve made it to America!

More lucid thoughts quickly followed, snapping me back into the present.

I had emerged from the dirt road, stepped into the highway and owed my life to the quick reaction time of a middle-aged woman with bleached-blond hair driving a shiny blue pickup truck. She rolled down her window to get a better look at me, stopped shouting, and scrambled from her vehicle. Her arms around my shoulders supported me as we staggered back to her truck.

I need help, I thought, but the words came out in Spanish. I saw her incomprehension, forced myself to concentrate and managed a language I hadn’t spoken for many weeks.

“Please,” I said in English, “Do you have a phone I can use? To call the police.”

She listened, openmouthed, as I offered the dispatcher enough information to convince him that the situation was beyond urgent. Then I disconnected. And my rescuer stopped me from walking back into the desert alone.

I sipped the bottle of lemon-flavored water she offered as I counted the minutes. A lifetime seemed to pass before the police arrived, before I could lead a convoy of police cars and ambulances to the abandoned trailer.

Within that lifetime, no one inside the trailer died.

Within that lifetime, a baby girl was born.