Читать книгу African Art - Maurice Delafosse - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Development of Negro Civilisations in Antiquity

Phoenician and Carthaginian Influence

ОглавлениеWe have, therefore, the right to suppose that these beads, perhaps of Phoenician manufacture, but in any case abundant among the Phoenicians, were first imported by them into the settlements that they had founded as early as the 12th century BC on the Mediterranean coast of Africa; that their colonists, Carthaginians and others, later introduced them into the Sahara even as far as Sudan; that Berber merchants, and then Arabs and Arabo-Berbers of Tripolitania, Tuat, Tafilalet and Dara or Draa continued this traffic, and that, after all, the men with long hair and of light colouration, of so-called celestial origin, mentioned by the Negro traditions, may have been successively Phoenicians, Punic, Berber, and Moorish caravan merchants.

As for the trace of Egyptian influence that voyagers have claimed to find in the houses of Djenné and in the pyramidal minarets of Sudanese mosques, it is useless to demonstrate its non-existence otherwise than in recalling that the constructions in question are subsequent to the Islamisation of the country of the Negroes and remind one singularly of a type of architecture which is widely spread in the Arabo-Berber country north of the Sahara. It is necessary to mention again the fantasy of those who have tried to discover the origin of the name Fula, Fulbe, or Fulani in that of the fellah of Egypt, without considering that fellah is an Arabic word serving to designate the peasants of any country and of any nationality and that there is no more a fellah of Egypt than of Morocco or Syria or any other place where there are people given to the cultivation of the land.

On the contrary, an attentive study of the facts leads me to formulate a hypothesis which, without doubt, will be verified with time and which would tend to attribute to the Phoenician colonies of North Africa, notably Carthage, a very considerable influence on the development of Sudanese civilisations, much more considerable and also much more direct, at least in that which concerns western and central Africa, than the influence having its point of departure in Egypt. This hypothesis does not rest only on simple conjectures.

In studying the words of Semitic origin which have acquired rights of citizenship in most of the Negro languages of Sudan and its hinterland, I have ascertained that, on the whole, they are divisible into two large categories which are very distinct from each other. The one relates almost exclusively to the dogmas and rites of the Muslim religion or to legal notions, hagiography and magic, which constitute the accessory baggage of all Islamisation; these, because of their meanings and the ideas which they represent, could not have been introduced except subsequently to the Hegira, they have not been borrowed from spoken Arabic but from written Arabic, and have passed into the Sudanese languages with the form – altered only by the Negro pronunciation – that they have in grammatical Arabic; they are thus words of scholarly formation. The other category comprises words serving to designate material objects – for example, pieces of harness, arms, utensils, clothing, etc. – or general ideas which are most often abstract, objects and ideas which the Negroes did not possess and hence borrowed at the same time as the vocables meant to represent them. These words have corresponding forms in Arabic, since, as I have said, they are incontestably Semitic; but they never answer to the grammatical form and they often depart enormously from the popular form Between the Arabic word and the word incorporated into the Sudanese languages, one does not find the alternating phonetics which are the law for the passage from Arabic into the Sudanese dialects of the words belonging to the first category: it seems, then, that the borrowing has been made from a Semitic language other than Arabic and, apparently, at a date far anterior to the introduction of Arabic into Africa. May not these words have been borrowed from Phoenician or Punic?

Whatever has been the scope of maritime expeditions undertaken by the Phoenicians and the Carthaginians and no matter how far Hanno and his companions may have gone towards the south, beyond the Pillars of Hercules, it is improbable that Carthage and other Phoenician colonies of Africa should have been able to establish continuous relations by sea with the Negroes. But it was certainly not the same by the way of land.

Carthage took from the Phoenicians, her founders, exceptional aptitudes for what one might call “long distance commerce”. Her citizens were not slow to perceive the advantages which they could procure by trading with the Negroes who, beyond the unproductive desert, inhabited fertile regions, rich in men and gold. They organised caravans which must have very closely resembled those which still circulate today across the Sahara and which travelled to Sudan in search of slaves, gold dust, ostrich feathers, and ivory, in exchange for textiles, clothing, copper and beads. These Carthaginian merchants undoubtedly did the same as their Tripolitanian and Moroccan successors do in our day: they were not content to escort their convoys of camels, they sojourned some little time in the country of the Negroes, settling in temporary colonies in the principal centres along the edge of the desert and, from there, just as the Moroccans do today, went out into the neighbouring provinces.

During hundreds and hundreds of years, there must have been other affairs than the exchange of products between Carthage and Sudan: there was contact between the still very rude Negroes and the representatives of one of the most refined civilisations known to antiquity. This contact could not but be fruitful. As I have just suggested, these Carthaginian merchants introduced among the Negroes, together with the new words designating or expressing them, new objects and new ideas. Undoubtedly, the horse, coming from Libya, was already known in Sudan but, also without doubt, was hardly utilised there: the Carthaginians taught the Negroes the art of equitation and the use of the bit, stirrups and saddle. At the same time that they sold them textiles and a sort of chemise, and they probably brought them the seeds of the cotton plant and taught them to weave cotton fibres and to sew goods. They also showed them how to work the gold which the Negroes had been content until then to extract from alluviums and, by imitation, the copper and bronze industries developed, while those of iron and clay became perfected and the glass industry was born and still existed in the last century in some localities of the Nupe on the lower Niger. Of course, all this is only supposition,[5] but it is probable supposition nonetheless.

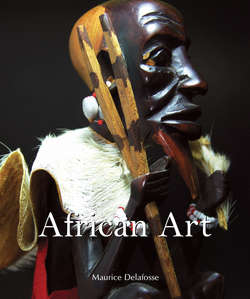

Mask (Bangwa). Cameroon.

Wood, encrusting, height: 27 cm.

Private collection, Brussels.

This mask from the secret society of Troh, in charge of maintaining order and fighting against criminals, was kept in a hut and watched by a servant.

Mask of the Troh Society (Bangwa).

Western Province, Cameroon.

Wood with a blackish encrusted patina, 27 × 19.7 × 27.5 cm.

Musée du quai Branly, Paris.

The guardians of the tradition of the secret society of Troh, who supervised funerals, the selection of a new chief, and his enthronement, consists of a council of nine dignitaries. Part of their attire, this helmet is passed through families from father to son, which implies that only nine masks are in existance. This mask consists of various spherical shapes for the brow, eyes, cheeks, and so on; we see a man in a pointed headdress whose face is in a slight, open-mouthed grimace, showing his filed teeth. The thick coating, proof of the great age of the mask, comes from years of ritual libation and fumigation. The Troh member to whom this belonged guarded it with great care.

5

Translator’s italics.