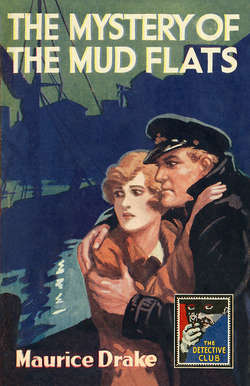

Читать книгу The Mystery of the Mud Flats - Maurice Drake - Страница 8

CHAPTER II CONCERNING A STROKE OF GOOD LUCK AND AN ACT OF CHARITY

ОглавлениеWITH the sun warming me, I must have slept for over an hour; but, lying face downwards as I was, even my dreams weren’t pleasant. I thought I had fallen overboard from the Luck and Charity, and rising half drowned under her stern called to ’Kiah for a rope. He was steering, but, instead of throwing me the mainsheet, he reached over a long arm, caught me by the side and pushed me under again. Drowning, I gulped salt water, and woke with a jerk, to find a girl standing over me prodding me in the side with her toe. Stupid with sleep, I rolled over and sat up, blinking to stare at her.

The sun, just over her head, dazzled my eyes so that I couldn’t clearly see her face; but from her get-up I judged her to be the usual type of summer visitor to the town. A big straw hat, a light blouse and dark skirt, and a bathing towel in one hand; but with the towel she held her shoes and stockings, and I saw that the foot that she had stirred me with was bare.

I asked her what she wanted, sulkily enough.

‘We want to go across the river.’ She pointed to the yellow sand-hills on the Warren side.

‘Well?’ I said.

‘There doesn’t seem to be a ferryman here. Don’t you want to earn a sixpence?’ Her tone was not conciliatory.

I looked down the beach. A man and woman stood by the waterside, but the boatmen had gone—to breakfast, I supposed. For a moment I was minded to tell her she must wait till they came back, but the thought of ’Kiah came into my mind. I owed it to him to make up what I could for the money I’d spent overnight.

‘I don’t expect my boat’s smart enough for you,’ I said, scrambling to my feet.

‘I didn’t expect anything lavish,’ she snapped; and at her tone I looked down over my clothes and passed a hand over my head and face. I didn’t look prosperous. One boot was broken at the toe, and my serge coat and trousers were stained with every shade of filth, from dry mud to tar, by the winter’s ’longshoring. I wore one of ’Kiah’s jerseys, Luck and Charity in dirty white letters across the breast. Bare headed, my hair was full of sand, and there was a fortnight’s growth on my cheeks. My razor, an elaborate safety fakement, had been sold early in the winter to get ’Kiah an oilskin jacket, and though I considered I had a right to shave with his, it was a right not often exercised. He’d inherited the thing from a grandfather who’d been in the army, and I didn’t share his high opinion of it. But in bright sunlight, with this girl staring at me, I wished I’d done so more recently.

The boat was in a state to match its owner. It couldn’t have had a coat of paint for two years, and to make matters worse the beach children had been playing in it and left it half full of pebbles, seaweed and sand. With the girl looking on, I started to clean out some of the rubbish, and the man and woman strolled along the water’s edge to join us. Feeling ashamed of myself and my shabby craft, I kept my head down and went on with my work till the man spoke.

‘An old boat?’ he said, civilly enough.

For an answer I mumbled some sort of assent.

‘Is she tight?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘I only bought her yesterday. She’ll take us that far without sinking, I suppose.’

He said no more and we pushed off. The filthy tub leaked like a basket, of course, and the water was level with the bottom boards before we reached the Warren. I saw what was going to happen when we started, and rowed my hardest to get across before their feet were wet, but facing them I had time to look them over and see what sort of people my first customers were. The other woman was a beauty—a real beauty, of the big, placid type. She said very little on the way across, just trailing one hand in the cool water now and again, and listening to the talk of the others. The man struck me favourably. He was tall and gaunt, with a bit of a stoop in the shoulders. His clean-shaven face was sallow and he wore spectacles, which gave him the air of a student of sorts. His big square mouth was immovable as the slot in a post office, save for an occasional movement at the corners that seemed to hint at a laugh suppressed. A man you took to at sight: straight as a line, you could see he was.

The girl who had waked me was of a different class from the other two. Now that I could see her more plainly I saw that she had a likeable little face enough, but you couldn’t call her a beauty anyhow. Big eyes and short upper lip were her best features; her nose was a snub, and she was well freckled, and wore her hair in a club sort of short pigtail. Her dress was shabbier than the other woman’s, and I took her for a paid companion, or rather a poor relation, which would account for their tolerating her impudence. She was full of life, chattering nonsense the whole way across.

I’ve learnt since that that young woman’s manners do occasionally cause embarrassment in well-bred circles. Blood will out: her grandmother was a mill hand, and the grand-daughter’s thrown back to the original type. She’s told me since that ‘Guttersnipe’ was one of her school nicknames, and like most school names it’s deadly appropriate. She’s got the busy wits and the quick tongue of the gutter, combined with the haste in action and the discerning eye for essentials that lifted her forefathers out of it.

The Warren beach was steep, and when they got out of the boat they had to scramble up a high slope of sand. The girls reached the level beach at the top and were out of sight at once; the man lingered to pay me. He hadn’t anything less than a shilling, and I couldn’t change it.

‘Take the shilling and call it square,’ he said, blinking at me through his spectacles.

‘The fare’s twopence a head. I don’t take charity,’ I said rudely.

‘No need to be rude, my man,’ said he. ‘Either you can trust me or you can take the shilling and bring me the change later. Here’s my card. I’m staying at the Royal.’

‘I don’t know when I shall be ashore again,’ I told him. ‘When are you going back to Exmouth?’

‘In about an hour, I expect. The ladies are going to bathe.’

‘Then I’ll wait till you come back and put you across again,’ I said. ‘That’ll make up the shilling’s worth.’

He nodded and scrambled up the beach after his womenfolk. No sooner was he out of sight than the younger girl’s head appeared against the sky and came slipping and sliding down over the steep bank of sand again. When she reached me she was breathing fast as though with running.

‘How old are you?’ she jerked out.

‘Twenty-eight.’

‘You were drunk last night, weren’t you?’

‘I was.’

‘You fool!’ she said.

Words can’t tell the scorn in her voice. It brought me up all standing, as though she’d slapped me in the face. Literally I couldn’t answer her; before I’d thought of a word she’d scrambled up over the slope again and was gone, leaving me staring after her like a baby.

When I got my wits about me I don’t know when I was in such a rage. The cheek of the little slut!

One thing I would do. I’d show her I was independent, at all events. Somebody else could row them back and spend my sixpence. I got into the boat again and pushed off to where the Luck and Charity lay at anchor.

It’s queer the way one’s resolutions change with one’s moods. ’Kiah was getting breakfast, but I kept mine waiting whilst I had a shave with his awful razor. After a wash I felt better and got overside and had a swim. Scrambling aboard the small boat her looks disgusted me, and I tidied her up as best I could, next thing, and put a couple of cushions from the cabin into her.

Doing this I heard a clock at Exmouth strike nine, and remembered it was eight o’clock when I had left Exmouth beach. I don’t pretend to explain it, but almost before I knew where I was I was rowing back to the Warren beach to await my fares.

I’d been thinking hard about the ckeeky girl, you may be sure, and a good breakfast and a wash had revived my self-conceit. Her slanging indicated that she took some interest in me, I thought, and I made up my mind I’d rout out my last decent suit of clothes and go ashore in the evening and try and pick her up on the promenade. Her behaviour had confirmed me in my notion that she was some sort of dependent, and I thought I could furbish up sufficient togs to impress her with the fact that I was a yacht owner. I’d take the starch out of her, I reckoned. No denying she’d waked me to an interest in her.

They kept me waiting half-an-hour longer. Whilst I was waiting I remembered the card the man had given me and searched my pockets till I found it. ‘Mr Leonard Ward’ was the name, and the address ‘Mason College, Birmingham.’

When they came down the beach the little girl gave me one look up and down, and then sat in the boat with her back to me all the way across, ignoring my existence. The man Ward gave me my shilling and offered to pay me for waiting, which I declined, and the three of them were strolling up the beach together when I was seized with a diabolical impulse.

‘Here,’ I called after them; and as they turned round, ‘You—the little girl. Miss—Pamily, is it? I want you.’

Her face went crimson, but she walked back to me.

‘My name is Brand,’ she said, very stately.

‘Pamela Brand?’ I asked.

‘Pamela Emily Brand. And what do you want of me, pray?’

‘I want to ask you something—two things. Why did you go for me just now like you did?’

‘Because I hate waste,’ she said. ‘What’s the other thing?’

‘Will you meet me this evening?’

It was her turn to be struck speechless now; she couldn’t get any redder than she was already. She looked over her shoulder to see if the man Ward was within call, and then, her face quick and alive with resentment, leaned over and with her open hand fetched my face a smack you could hear fifty yards down the beach. She’s a lady, I tell you! And before I’d recovered, she was marching off with her nose in the air—just boiling with rage, I knew; and I laughed aloud, for all my stinging cheek. I’d drawn her. I’d teach her manners—the gutter-bred little prig.

Rowing back to the Luck and Charity I resolved more than ever to go ashore and seek her out that very evening. Now that she was piqued, I knew she would welcome any advance on my part as giving her an opportunity for revenge. So the first thing I did after scrambling aboard was to look out my best suit of clothes and give them a brush up. Then I turned in to get an hour or two of decent sleep.

Judging from the way the ship’s head was laying, and from the sunlight streaming through the doorway on to the floor, I guessed it must be about half-past two, and three-quarters flood, when I was waked by a boat bumping alongside and by someone climbing on our deck. ’Kiah was about, I knew, and reckoning he could attend to any visitor, I turned over and was trying to doze off again when he swung himself down the companion stair, barefoot.

‘Gen’leman to see you, sir,’ he said.

‘What name?’ I called after him.

A mumbled inquiry, and the voice of my morning customer in answer.

‘Tell him Mr Ward wants to see him. He had my card this morning.’

So Miss Brand had called in male assistance. Somehow I hadn’t thought that of her; but I hadn’t any particular objection to a row, so pulled my boots on and went on deck, stretching myself. He was sitting on the bulwarks, looking aloft, a hired boat and man hitched alongside.

‘Good afternoon,’ he said civilly.

‘Afternoon,’ I answered. ‘Want me?’

‘Yes. I—I—want—’ He hesitated. ‘I understand you want to hire this boat on a charter?’

‘I wanted to sell her and clear out to sea,’ I told him. ‘Failing that I wouldn’t mind a charter, certainly. But she’s not fit for a yacht. Her cabin fittings are stripped, and there’s nothing under this hatch roof but smashed bulkheads and driftwood.’

‘I don’t want a yacht. It’s for the coasting trade. How many tons could you get into her, and what water would she draw, loaded?’

‘Not more than about sixty tons, I should think. And I don’t know about draught. Something under nine feet, for certain. She’d never pay. You’d want three men, and how’s the freight on sixty tons to pay their wages?’

‘The draught is the point,’ he said. ‘They’re shallow waters I want her for. We can’t use a bigger boat very well. In fact, it’s just this small class of vessel I’m down here to look out for. She’s staunch, isn’t she?’

‘Sound as a bell,’ I assured him. ‘Come below and have a look at her, and then you can tell me just what you do want.’

We went all over her, and he seemed an intelligent man, from his comments. Being evidently shore-bred. he couldn’t see how badly she’d been stripped, of course, but the few questions and remarks he did make were all to the point. After going through the hold and forepeak we went aft into my cabin and sat down.

‘She’ll suit my purpose,’ he said, and looked across the table at me inquiringly.

‘Where do you want her to go to?’ I asked.

‘To and from the Scheldt,’ he said. ‘I am a director of a small company trading at Terneuzen, in the Isle of Axel. We have a couple of boats on charter now, but we’re busy and can do with another, for a year at least. You would take our goods from English ports here on the south coast, returning in ballast. What ballast did you say this boat wanted?’

‘Summer, fifteen tons or so; winter, twenty-five, I daresay.’

‘You can allow for more than that,’ he said. ‘We’re excavating beside our wharf there and are glad to get the mud taken away. So you needn’t blow over for want of ballast. And now as to terms.’

We discussed terms easily enough. Thinking such a small company as he described would be sure to haggle. I asked twice what I was prepared to take, and he accepted on the nail. After that, I was almost ashamed to point out that I should have to ask for an advance.

‘The boat isn’t fit for sea as she is,’ I explained. ‘I’ve sold all my spare stores, and shall have to pay for labour as well as fit her out. If you’re in a hurry, that is. I daresay my man and myself could get her rigged in a month or five weeks.’

‘That won’t do,’ he said. ‘I want you to get under way just as soon as you can. We’ll advance you fifty pounds. Will that be enough?’

I nodded. ‘That’ll be ample. As to security? I’ll give you a mortgage on the boat herself.’

He seemed to approve of the suggestion. ‘That’s business,’ he said. ‘I’ll get the mortgage prepared at once, and you can have the cheque when you please. You’ll want to take on another man or two, won’t you?’ He got up and went on deck, me feeling almost dazed with my good luck.

He shook hands as he was going over the side. ‘By the way, I shall want your name and address.’

‘My name’s West—James West.’ It didn’t seem quite the occasion to drag in the Carthew hyphen part of the business. ‘As to address, I haven’t one ashore. You’d better describe me as master and owner of the ketch Luck and Charity, registered at Plymouth.’

‘That’ll be good enough,’ said he, and went down into his boat and was rowed away, leaving me fit to jump with delight.

‘What du he want?’ ’Kiah asked.

‘Sir,’ I shouted at him. ‘Say “sir,” you uncivil Topsham dab.’

‘Yu ’eaved flukes at me for callin’ ’ee “sir” yes’day,’ he protested.

‘That was because you were my partner then. Now you’re my crew, my first orficer, my navigating loo-tenant, my paid wage-slave. We’ve got a job, ’Kiah. Your wages are doubled as from last October. You’ll have a lump of arrears to draw tomorrow. Go and wash your face, and then go ashore and spend the money I got for the dinghy last night. In meat, d’ye hear? A duck, and green peas, and a cold apple tart at Crump’s, and cream to eat with it. Us’ll feed like Topsham men when the salmon comes up river, ’Kiah. Us have got a job, ’Kiah—a twelvemonth charter-party at good money—and us draws fifty quid tomorrow. D’ye understand, you plantigrade?’

‘Caw!’ said ’Kiah cheerfully, and went forward to wash himself before going ashore.

When I woke mext morning it struck me I’d been in rather a hurry to take the man Ward at his word; but the confidence wasn’t misplaced, for he came aboard at eleven with the cheque in his pocket and the mortgage deed ready for signing. That was soon done, and he handed me the money and my first instructions. I was to get the topmast up; replace the missing stores and victual the boat; hire an extra hand and proceed to Teignmouth, there to load clay for Terneuzen. My consignee was a Mr Willis Cheyne, the company’s representative on the spot, and I must look to him for further instructions.

The rigging once started we worked double tides. I took on two men instead of one, and drove them for all I was worth, intending to take whichever proved the better of them to sea with me. They turned out to be a pair of crawling slugs, and I sacked them the third day and looked for another couple to take their place. But the tourist season was beginning, all the best men on the beach were busy, and the report spread by my two failures discouraged the others. In the end ’Kiah went to Topsham one evening and returned with a cousin of his, a Luxon—everybody in Topsham is called either Pym or Luxon—and we three finished the job in a week from the day the other two were sacked. Ward was aboard nearly every day, and once he brought his womenfolk with him. I was aloft, too busy to do the polite, so I shouted to him to make use of the cabin and went on reeving the peak halliards. The Pamily girl scowled up at me till she must have nearly got a crick in her neck, but I gave her a friendly wave of the hand and after that saw no more of her than the top of her big straw hat. Foreshortened, she looked like a mushroom wandering about the deck.

Luxon was just such a silent shockhead as ’Kiah himself. I never learnt his other name; ’Kiah always called him ‘Banny,’ which was obviously impossible. The job done, he drew his money arid went ashore without a word to me of his future intentions, but ’Kiah explained he wouldn’t come to sea with us. ‘’E reckons ’e’d ruther stay ’ome,’ was all I could get out of, him.

The evening before we left Exmouth I was in the dock entrance, filling our water-breakers from the hose where the ferry steamers water, when a voice hailed me from the top of the steps and asked if I was the ferry.

‘What ferry?’ I asked, without looking up.

‘Across the river. To—Dawlish, is it? I want to keep along the coast road.’

‘You’ll find the Warren ferryboat on the outer beach. There’s a steam ferry leaves here for Starcross in half-an-hour or thereabouts.’

‘What good’s a sixpenny steam ferry to me? I’m on the road;’ and the owner of the voice came down and sat upon the steps just above me.

He was on the road and no mistake about it. I never saw such a long, lean, broken-down tramp in my life. His coat and shirt were worn through at the elbows, showing his thin, bare arms. The holes in his ragged tweed trousers showed he had on another pair of blue serge underneath, both pairs frayed to fringes at the heels. He wore no hat, and his boots were past even a tramp’s repairing. As he sat, he took one off, looked at it whimsically with his head on one side, and threw it into the dock, and then served the other in the same way.

‘It’s a pity to separate ’em,’ he said cheerfully. ‘True, they never were a pair, but they’ve done a good few miles in my company.’

‘You’re a chirpy bird,’ I said.

‘Of course I am,’ said he. ‘Why not? Six months ago I wasn’t given as many weeks to live, and yet here I am, fit and well, thanks to God’s fresh air and a sane life. I’ve neither house nor farm nor fine raiment to bother me, nor woman, child nor slave dependent on me. I’ve even half-a-lung less to carry than you have, by the healthy look of you. My hat once on, my house is roofed.’ He put his hand to his head. ‘I forgot. It blew over the cliff a few miles back. All’s for the best in this best of worlds. That’s another worry the less.’

‘You’ve got two pairs of trousers,’ I suggested.

‘True, O seer. A concession to public tastes. They are selected so that the holes in the inner pair do not correspond with those in the outer, and thus decency is observed. And now what about this ferrying business?’

I had got my water-breakers aboard the boat and was stowing them between the thwarts. ‘Jump in,’ I said. ‘I’ll put you across.’

‘I may as well warn you that I haven’t a sou to my name,’ he said. ‘You’ll have to work for love. I’ll take an oar and work my passage, if you like.’

It wasn’t the first time he’d been in a boat, evidently, for he came aboard neatly, without stumbling or awkwardness, took the oar I proffered him, and handled it very fairly.

Half-way across I asked him what he was doing at Dawlish.

‘Nothing, I expect. I’ve given up asking for jobs. It’s much easier to ask for grub. Almost anybody’ll give you that in this dear land of mine—poor folk especially—but work isn’t so easy to get. Besides, I’m an unhandy fool at the best. I never learnt any trade worth knowing.’

‘Have you a trade?’

‘Bless you, yes. I’m a pressman—or was, before my lungs began to go. The doctors ordered me fresh air and exercise in a mild climate and I’m getting them tramping the South of England. Then I was fat and flabby and unhealthy and morose; now I’m the lightest-hearted wastrel on earth, and I’ve stopped spitting blood these last two months.’

‘What are you going to do when the winter comes?’

‘Don’t know. Same thing as before, I suppose, unless I can ship south in some packet or other.’

I pricked up my ears. ‘Ship south, eh? Are you a sailor man?’

‘I used to report the big regattas for The Yachting Gazette,’ he said. ‘I had to know one end of the boat from the other to do that.’

‘Feel like supper aboard my boat?’ I pointed to where lay the Luck and Charity, just visible in the gathering dusk.

‘Nothing I should like better,’ he said airily, so we went aboard and I set before him cold fried sausages and baked mackerel.

The man was ravenous—almost starving—and he ate like a shark, I watching him across the table. In the lamplight one could see him better, and upon examination he wasn’t such a bad looking tramp. He had a short black beard and moustache, his hair was close-clipped, and, for a wonder, he was clean, save for the dust of the roads upon his tattered clothing. Lean as a lath, his cheekbones stuck out and his eyes were sunk in their sockets, yet he looked like what he had claimed to be, fit and well and sunburnt to a healthy brown.

After he wiped the dishes dean he got up.

‘Shall I wash up after myself?’ he asked.

‘No hurry. Sit down and chat. D’you smoke?’

‘When I get the chance. Thanks.’ He produced cigarette papers from some corner of his rags and rolled and lit a cigarette of my tobacco. Inhaling a few breaths luxuriously, he began to look about him. ‘Books—books,’ said he, and got up again to run his nose along my little shelf. ‘Practice of Navigation, Ainsley’s Nautical Almanac, South of England Cruises. Hullo! Pecheur d’Islande. D’you read Loti?’

‘With a dictionary handy.’

‘Good man. Pecheur d’Islande takes a bit of beating, don’t it? Henry James’s American, too.’

‘I’m trying to break myself in to him. The American’s readable.’

‘Readable! You savage. Half-a-mo’, though. Balzac. Marcus Aurelius. What sort of ship d’you call this?’

‘The Luck and Charity, coasting ketch.’

‘The Luck’s mine, the Charity yours. Extend it to a night’s shakedown, will you? A heap of old sails in any lee corner’ll do me well. I’m dog tired—and I give you my word I’m not verminous.’

‘You’re welcome,’ I told him. ‘Turn in when you like. I’ve got to be about early tomorrow morning—we’re going round to Teignmouth to load.’

As luck would have it, the Teignmouth tug brought up a vessel next morning, and as she was going back alone I bargained for a cheap tow round. In the hurry I forgot my guest, and when he came on deck we were passing the harbour mouth.

‘Shanghai’d me, have you?’ he said.

‘I forgot you. We’re only going as far as Teignmouth this trip. That won’t take you off your road, will it?’

‘Any road’s my road,’ he said philosophically. ‘Can I be of any use?’

‘Can you cook?’

‘Near enough, I expect,’ said he, and set ’Kiah free by frying the breakfast, which he did very well.

I was messing about the deck afterwards, tidying up a little, and took a pull on the topsail halliards, which were new stuff and were loosening in the sun. The other end of the rope was insecurely hitched, and my down haul pulled it off the pin and just out of reach. It began slowly to slide aloft over the sheave and was quickening pace when the tramp went up the shrouds like a lamplighter and caught it at the crosstrees.

‘You’ve done some sailoring,’ I said, when he came down, the free end in his teeth.

‘Yachting,’ he said shortly. ‘Just enough to know my own uselessness.’

‘Good talk,’ I said. ‘Care to ship with me aboard this packet. We want a man.’

‘What’s the trade?’

‘South Coast to the Scheldt, I understand.’

‘Sounds good enough,’ he said. ‘But I’m supposed to be an invalid of sorts. I may not be up to the mark, but I’ll try it for a bit, if you’ll have me, on one condition. I’m to chuck it any day I please without any nonsense about giving notice on either side.’

‘All right. We’ll see how it works. If you can’t stick it, you can’t; if you can you’ll be company for me. What’s your name, by the way?’

‘Voogdt.’

‘What a name! Dutch?’

‘My grandfather was. It’s a good enough name for me.’

‘No offence,’ said I, for he sounded testy. ‘Only we seem to have a rum collection of names here. Mine’s Carthew-West, the boat’s the Luck and Charity, the first mate is Hezekiah Pym, and now we’ve shipped a crew called Voogdt.’

‘Austin Voogdt, if you want the lot of it,’ he said, in perfect good temper once more. And so we came to Teignmouth with our full ship’s company.