Читать книгу The General - Max Hastings, C. Forester S. - Страница 5

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеNo warrior tribe in history has received such mockery and contempt from posterity as have been heaped upon Britain’s commanders of the First World War. They are deemed to have presided over unparalleled carnage with a callousness matched only by their incompetence. They are perceived as the high priests who dispatched a generation to death, their dreadful achievement memorialised for eternity by such bards as Siegfried Sassoon:

‘Good morning; good morning!’ the General said

When we met him last week on our way to the line.

Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of ’em dead,

And we’re cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

‘He’s a cheery old card,’ grunted Harry to Jack,

As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack.

But he did for them both by his plan of attack.

Two generations later, Sir John French, C-in-C of the wartime British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front, together with his successor Sir Douglas Haig, were caricatured by Alan Clark in his influential though wildly unscholarly 1961 polemic The Donkeys, for which the author belatedly admitted that he had invented the quotation attributed to the Kaiser, describing British troops as ‘lions led by donkeys’. Clark’s book inspired Charles Chilton and Joan Littlewood to create the 1963 satirical musical Oh, What A Lovely War!. In 1989 BBC TV’s Blackadder Goes Forth imprinted on a new generation of viewers a vision of 1914–18’s commanders personified by General Sir Anthony Cecil Hogmanay Melchett, played by Stephen Fry. Here was the mass murderer as comic turn – or, if you prefer, the comic turn as mass murderer.

Yet this was not how most survivors of 1914–18 viewed their leaders in the war’s aftermath, despite gaping emotional wounds left by the slaughters at Neuve Chapelle, Loos, the Somme, Ypres, Passchendaele and elsewhere. Among veterans returning from France, there was anger about the muddle attending demobilisation of Britain’s huge army, which prompted strikes and mutinies; about the lack of a domestic social, moral or economic regeneration such as might offer some visible rewards to justify the war’s sacrifice; about the absence of the ‘homes fit for heroes’ promised by politicians. But until the end of the 1920s, senior officers such as Haig, French, Plumer, Byng and Rawlinson received respect and even homage. The belated victors of the campaign on the Western Front were loaded with titles and honours; painted by Sir William Orpen; granted places of honour at the unveiling of countless memorials, of which the Cenotaph in Whitehall was only the foremost. A million people turned out for Haig’s 1928 London funeral procession, and almost as many for the subsequent ceremonies in Edinburgh.

The public mood began to shift about the time the Depression began. Such accounts of the war as Frederick Manning’s The Middle Parts of Fortune (1929), Edmund Blunden’s Undertones of War (1928), Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928) and Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930), Robert Graves’s Good-bye to All That (1929) and Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1929) depicted a protracted agony in pursuit of rival national purposes which allegedly meant little to those who perished in their names, compounded by the brutalism of those who directed the armies.

Even if most veterans – unlike Maynard Keynes and Siegfried Sassoon – retained a belief that the allied cause had been just, people could see for themselves the political chaos and economic wretchedness prevailing across much of the world at the end of the decade following the armistice. The Great War, it seemed, had not merely yielded battlefield horrors of unprecedented scale and intensity; it had also failed to secure any discernible benefit for mankind or even for the victors. In the absence of evidence of Germanic evil remotely matching the 1945 revelation of the Holocaust, by the 1930s a diminishing number of people in the allied nations acknowledged the Kaiser’s empire as a malign and aggressive force, the frustration of whose purposes had been critical for European civilisation. Britain became host to a Peace Movement unrivalled in any other country for its numbers and fervour. Following the Oxford Union’s February 1933 debate, in which a motion was carried by 275 votes to 153 ‘that this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country’, many people believed that a new generation of British men had become irredeemably committed to pacifism. In 1934 Madame Tussaud’s waxwork gallery responded to the changed public mood by removing from exhibition its galaxy of allied generals, catalogued as ‘The Men Who Won the War’.

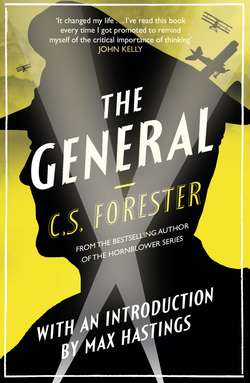

It was in this climate that C.S. Forester, then emergent as one of the most popular novelists of his generation, wrote The General. The author, whose real name was Cecil Louis Troughton Smith, was born in Cairo in 1899, son of a minor government official. Educated at Dulwich College, he was rejected for military service in 1917 on grounds of poor eyesight and general physical frailty. He spent three years as a medical student before abandoning this path in 1921 to pursue a writing career. Success came relatively slowly; only in 1926, after publishing several deservedly unnoticed pieces, did Forester win attention for Payment Deferred, a novel about a man who murders his rich nephew and escapes consequences until his wife exacts an ironic but appropriate penalty. The book caught the eye of Charles Laughton, who embraced it as a star vehicle for himself in highly successful stage (1931) and film (1932) versions, which also propelled its author towards fame and prosperity.

Forester thereafter displayed versatility as well as high gifts as a storyteller, penning histories and historical novels which achieved a worldwide audience, while also serving as a Hollywood scriptwriter. His books focused upon the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with a special emphasis on naval yarns, of which the first was Brown on Resolution (1929), a superbly accomplished, wry tale about Albert Brown, a sailor whose short life climaxes on a barren Pacific islet in 1914 after he has become sole survivor of his old British warship’s encounter with a German raiding cruiser. The African Queen (1935), which later became a movie starring Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn, wove a quirky love story around one of the lesser-known episodes of World War I, the Royal Navy’s December 1915 sinking of a German gunboat on Lake Tanganyika. Other early novels were set in the Napoleonic Wars, to which the author would return for the 1937 creation of Captain Horatio Hornblower, the character with whom his memory remains most famously associated, favoured leisure reading of Winston Churchill in World War II.

But Hornblower still lay in the future when Forester wrote The General, which more than a few admirers, myself and the author among them, believe to have been his best work. In all his writing he displayed a fascination with awkward human beings, unglamorous figures who nonetheless achieved notable deeds, some base, others heroic. By 1936, when the book was first published, a growing minority of British people feared that it would prove necessary once more to fight Germany, this time under Hitler, making mock of the post-1918 slogan ‘Never again.’ For a season, however, the Peace Movement and its collateral branch, the appeasers, still held sway. Abomination of the Western Front’s generals had not reached the peak it would achieve thirty years later, and has since retained, but there was assuredly revulsion towards the bloodbaths which the ‘brass hats’ had directed.

Captain Basil Liddell Hart, who served briefly and without attracting much notice on the Western Front, had transformed himself into a widely read pundit on military affairs. In this role he did much to advance the legend of British command idiocy, initially through his 1930 study The Real War, later extended and republished as A History of the World War (1914–1918). Sir Hew Strachan has written that the book ‘posed as an objective analysis of military operations. In truth it is a sustained critique of the British high command, and its purpose is more didactic than historical.’

Liddell Hart was prejudiced, if not embittered, by the unwillingness of the British Army’s senior officers to treat himself as seriously as he believed his gifts as a strategic thinker merited. He was a fluent writer who sustained a prodigious output of journalism, books and correspondence. He developed some good and even important ideas which, like most theoreticians, he habitually overstated. Foremost among them was the claim that exploitation of manoeuvre and technology – most conspicuously, the tank – could have played a game-changing role earlier in the First World War, and would certainly do so in future conflicts, without the necessity for murderous headlong collisions.

Liddell Hart’s denunciations of 1914–18 commanders’ myopia, and assertions of their culpability, won favour with some important people, including Lloyd George, Winston Churchill – and C.S. Forester. The strategic guru’s vision pervades the novelist’s tale about an officer who rises to high rank in the First World War. Forester was encouraged to write it by Michael Joseph, a flamboyant and gifted publisher. Joseph, born in 1897, had served on the Western Front as an officer in the Machine-Gun Corps, being badly gassed before coming home to marry – briefly – the actress Hermione Gingold. In 1936 he had just started his own publishing house, which thereafter midwifed all Forester’s work. The author inscribed The General to him ‘not as the “onlie begetter”, but nearly so’. On 2 January, Joseph wrote to Basil Liddell Hart, asking him to read and comment upon Forester’s proofs. The pundit responded that he was immensely busy, but could not resist a book by an author whom he did not know personally, but much admired.

On 8 January he wrote at length, saying that having finished The General he was impressed, and would make no proposals for major changes: ‘It is so true a picture, with so telling a message, that I feel nothing ought to be risked that might dim it.’ He added a list of twenty detailed comments and corrections – a cavalry regiment had three sabre squadrons, not four; a corps never contained more than three divisions; Sir John French was sacked as C-in-C of the BEF in December, not October 1915, and suchlike. Cajoled by Michael Joseph, Liddell Hart also provided a pre-publication ‘puff’ for the book: ‘It is superb … in its combination of psychological exposure and balance.’ Forester and Liddell Hart met early in 1937, the first encounter of what became a close and mutually admiring friendship. On the novelist’s death in 1966 the military commentator was among those to whom he left legacies of $1,000 apiece as tokens of esteem.

Forester starts the portrait of his hero, or anti-hero, with one of the more droll first sentences in fiction: ‘Nowadays Lieutenant-General Sir Herbert Curzon, KCMG, CB, DSO, is just one of Bournemouth’s seven generals, but with the distinction of his record and his social position as a Duke’s son-in-law, he is really far more eminent than those bare words would imply.’ The author set himself to understand and explain what manner of man could have done as the commanders of 1914–18 did: launch repeated doomed assaults that killed their own troops in tens of thousands, some before they reached the British front line, never mind the German one.

Before I took my wife on a first visit to the battlefields of the Western Front, I recommended The General as background reading ahead of any work of history, and she devoured it eagerly. To appreciate Forester’s book, no grasp of strategic studies is necessary. This is pre-eminently a human story, enhanced by its bathetic romance between a tongue-tied, socially corseted cavalryman on the wrong side of forty and a duke’s unhappy and unlovely spinster daughter: ‘for a fleeting moment Curzon, as his eyes wandered over her face, was conscious of a likeness between her features and those of Bingo, the best polo pony he ever had’. The author writes sympathetically about the sexual problems which dogged so many marital relationships in those ignorant, if not innocent, days. Above all, he tells the story of a wartime officer’s rise from obscurity to arbitration of the destinies of 100,000 men – which, as the author remarks, were more than Marlborough or Wellington ever commanded.

The book received a warm critical reception. H.G. Wells described it as ‘a portrait for all time of an individual in his period’. An American reviewer wrote: ‘Here is a book in which fiction masquerades, with complete success, as biography … More than the story of a man, this is a revealing study of the military mind, the military caste and the military system … Herbert Curzon represented the finest flowering of the officer type that was shaped and bred and groomed for command by the Old British Army.’ The writer credited the novelist with presenting, ‘with superb clarity and ironic definition, a few notable scenes from an ancient and enduring farce’. The Times was tepid, but the Daily Mail dubbed the book ‘masterly’: ‘Mr. Forester is uniformly just to his general, with effects that are sometimes startling.’ In the Evening Standard, Howard Spring wrote: ‘Everything that Curzon had was fine: courage, endurance, impartiality, honour. But in this great and moving study Mr. Forester shows how little even these avail when man’s divine element, the imagination, has flickered out.’ Spring described Curzon as ‘a well-nigh flawless creation’.

The book was not a big seller: it addressed a theme for which the British public had scant appetite. But word of its excellence travelled swiftly through service messes. Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, soon to become Battle of Britain C-in-C of Fighter Command, told Liddell Hart he thought the novel ‘marvellous’, as did General Sir Tim Pile. One American reviewer, never before having heard of Forester, speculated that he must have served in France, to possess such insight into what had taken place there. In truth, of course, the author had never experienced a day of military service, nor heard a shot fired in anger. Some modern novelists who write about conflict in general and the First World War in particular sell well, but expose to knowledgeable readers a profound ignorance of military affairs. Forester, by contrast, displayed in The General a mastery of soldiers’ conversation and behaviour, as well as of the machinery of war, which few writers have matched.

Whether he described the thought processes of sergeants or the social conventions of officers’ messes, he seldom faltered or struck a false note. He recognised that in 1914’s cavalry units, the post of machine-gun officer was often given to the regiment’s least plausible horseman, rather than to its brightest spark. He perfectly grasped the respective functions of divisional, corps and army commanders – he knew what generals did. He astutely observed the politicisation of wartime senior soldiers, who discovered the importance to their careers of dinner-table intrigue; the novelist shows Curzon unwillingly joining this game. His account of his subject’s experience in the October–November 1914 First Battle of Ypres achieved a verisimilitude he can surely have achieved only by interrogating survivors.

Forester was also a perceptive observer of the British social system, and especially of the lower middle class. This enabled him to write wittily and well about the bourgeois origins of his general, the perils of his ascent into the world of unkind hearts and coronets. Curzon belongs in Forester’s extensive fictional gallery of awkward, limited human beings. In an early chapter, the author describes this prematurely middle-aged bachelor, with his DSO won in South Africa fighting the Boers, as he was on the eve of war in 1914, a picture which

seems to verge closely on the conventional caricature of the Army major, peppery, red-faced, liable under provocation to gobble like a turkey-cock, hide-bound in his ideas and conventional in his way of thought, and it is no more exact than any other caricature. It ignores all the good qualities which were present at the same time. He was the soul of honour; he could be guilty of no meannesses, even boggling at those which convention permits.

He would give his life for the ideals he stood for, and would be happy if the opportunity presented itself. His patriotism was a real and living force, even if its symbols were childish. His courage was unflinching. The necessity of assuming responsibility troubled him no more than the necessity of breathing. He could administer the regulations of his service with an impartiality and a practised leniency suited to the needs of the class of man for which those regulations were drawn up. He shirked no duty, however tedious or inconvenient; it did not even occur to him to try to do so … The man with a claim on his friendship could make any demand upon his generosity. And while the breath was in his body he would not falter in the face of difficulties.

Although a part of Forester disdained his principal character and the role his kind had played in the greatest human tragedy ever to befall Britain, the author’s sense of justice caused him also to recognise his general’s merits. Curzon commanded respect and indeed affection from his staff and subordinates as a tireless worker and dedicated professional, of the highest courage both physical and moral. As a corps commander, he displayed intelligence enough to recruit to his staff civilian experts in chemistry, railway scheduling, logistics and suchlike, and to make full use of their skills, such as he knew himself to lack. Forester concluded his portrait: ‘So much for an analysis of Curzon’s character at the time when he was to become one of the instruments of destiny. Yet there is something sinister in the coincidence that when destiny had so much to do she should find tools of such high quality ready to hand. It might have been – though it would be a bold man who said so – more advantageous for England if the British Army had not been quite so full of men of high rank who were so ready for responsibility, so unflinchingly devoted to their duty, so unmoved in the face of difficulties, of such unfaltering courage.’

This has seemed to me, since first I read Forester’s lines at the age of fourteen, one of the most vivid character sketches he ever made. Among much else, it showed his recognition that to brand the commanders of 1914–18 as cowards, who chose to lead from the back – one of the charges made by some war poets – was unjust: fifty-eight British general officers perished in the conflict. Moreover, it is no more sensible to view those men as clones of each other than to delineate any other group of professionals and contemporaries in such a way. But there was indeed a British military caste, which had its German, Russian and French equivalents, and Curzon seems a fair exemplar.

Among the more foolish of popular proverbs is that which claims ‘Cometh the hour, cometh the man.’ Occasionally in the course of history, great challenges have brought forward great leaders – Pitt in the 1790s and Churchill in 1940 are obvious examples. More often, however, societies have been obliged to respond to threats to their security and even existence under the direction of unimpressive statesmen and bungling soldiers. In the Napoleonic Wars, with the possible exception of Sir John Moore who perished at Corunna, it was only with Wellington’s appointment as Peninsula commander-in-chief in 1809, after almost two decades of intermittent European strife, that Britain identified a commander of the highest gifts to lead its forces on the Continent. Few societies put their best brains in their armies, and clever people are usually more profitably employed elsewhere. Such a distribution of national talent becomes a handicap only when great wars break out, and in 1914 a century had elapsed since Britain’s last one. Forester portrays a calamity which dwarfed its military actors by its scale and intractability.

Although the novel’s claim to minor-classic stature seems hard to dispute, in one important respect it is flawed. It was informed by a belief, derived from Liddell Hart and his kind, that better allied generalship could have secured victory at lesser cost. This view suffuses the pages of The General: an assumption that Curzon, like his real-life counterparts, lacked the imagination to adopt methods which could have overcome the difficulties of confronting the German army in France and Flanders. In a seminal passage of the book Forester describes how, after the failure of the British attack at Loos in October 1915, the commanders of the British Expeditionary Force discussed preparations for a new offensive with more men, more guns, more shells, more gas:

‘In some ways,’ wrote the author, ‘it was like the debate of a group of savages as to how to extract a screw from a piece of wood. Accustomed only to nails, they had made one effort to pull out the screw by main force, and now that it had failed they were devising methods of applying more force still, of obtaining more efficient pincers, of using levers and fulcrums so that more men could bring their strength to bear. They could hardly be blamed for not guessing that by rotating the screw it would come out after the exertion of far less effort; it would be a notion so different from anything they had ever encountered that they would laugh at the man who suggested it.’ Here the novelist displayed the mindset that caused Churchill to write at the same period: ‘Battles are won by slaughter and manoeuvre. The greater the general, the more he contributes in manoeuvre, the less he demands in slaughter.’

Where both Churchill’s dictum and Forester’s analogy were fundamentally mistaken, in the view of the best modern scholars of the First World War, was in their failure to acknowledge that no military means then existed to make possible a ready ‘rotation of the screw’, to open any cheap and ready path to victory. To pose such questions as are asked by some modern critics of Great War generalship, ‘Could they not have invented tanks sooner?’, is as meaningless as demanding, ‘Might the Schlieffen plan have worked if the Germans had Panzer divisions?’ The Western Front’s dominant reality was that the available means of defence proved more effectual than the means of attack. Even when, at terrible cost, one side or the other’s assaults achieved an initial breakthrough, the necessary mobility was lacking, together with appropriate command and control technologies, wirelesses then being cumbersome and primitive, rapidly to reinforce and exploit local success. This changed only in the summer of 1918, when the German army was much weakened by attrition, and the British had developed new tactics – above all through the sophisticated management of artillery – for which Haig deserves significant credit.

Even in the Second World War, Liddell Hart’s faith in an ‘indirect approach’, the possibility of attaining victory by manoeuvre rather than attrition, proved justified only where defenders suffered a moral collapse, as did the French in 1940, the Italians in 1941, the Russians in the first months of Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa, the British in Malaya in 1942. When a defending army displayed staunchness and professional competence, like the Wehrmacht in almost all circumstances, and the Japanese in most of their 1944–45 island battles, Liddell Hart was shown to be quite mistaken in supposing that enlightened generals could readily cut keys to victory.

Between 1914 and 1918, British and French commanders were imprisoned by strategic realities, foremost among which was that if the allied armies remained supine in their trenches, they thus acquiesced in enemy occupation of a large swathe of France and Belgium, in which five million people lived under brutal subjection. Herein lay the answer to the oft-asked modern layman’s question: ‘Why did the allies keep attacking?’ Moreover, the Germans enjoyed another considerable advantage, that they could concede a few yards or even miles of occupied territory wherever it seemed tactically expedient to do so – to entrench on higher ground, for instance – while it was politically unacceptable for allied formations voluntarily to yield French or Belgian soil, even if doing so would save lives. Over all loomed the cruel truth that the only ready means of escape from the horrors of the Western Front was to concede victory to the Kaiser.

But if 1914–18’s generals deserve sympathy for the intractability of the military challenges they faced, to modern eyes they still seem repugnant for their indifference to the massacres over which they presided. A vivid insight into their emotional processes, or lack of them, was provided by the 1952 publication of Sir Douglas Haig’s diaries. For instance, the BEF’s C-in-C wrote on 2 July 1916, amid the Battle of the Somme: ‘A day of ups and downs! … I visited two Casualty Clearing Stations … They were very pleased at my visit. The wounded were in wonderful spirits … The A[djutant]-G[eneral] reported today that the total casualties are estimated at over 40,000 to date. This cannot be considered severe in view of the numbers engaged, and the length of front attacked. By nightfall, the situation is much more favourable than we started today.’ Next day, Haig added: ‘Weather continued all that could be desired.’ Winston Churchill, who knew the senior officers of the war intimately both as a cabinet minister and, for some months, as a battalion commander on the Western Front, penned a vivid portrait of the wartime C-in-C, soon after Haig’s death in 1928:

He presents to me in those red years the same mental picture as a great surgeon before the days of anaesthetics, versed in every detail of such science as was known to him; sure of himself, steady of poise, knife in hand, intent upon the operation; entirely removed in his professional capacity from the agony of the patient, the anguish of relations, or the doctrines of rival schools, the devices of quacks, or the first-fruits of new learning. He would operate without excitement, or he would depart without being affronted; and if the patient died, he would not reproach himself.

Forester’s Herbert Curzon was a subordinate officer rather than a warlord, but in this respect he exemplified his real-life superiors as well as his peers. His own diary, had he kept one, would have resembled Haig’s. He was a Roman, schooled since childhood to regard fortitude in the face of difficulties and losses as an indispensable virtue for every right-thinking soldier, a view shared by the senior officers of Russia, France, Germany, Austria, Italy. What seems to a twenty-first-century society to have been harsh insensitivity was, to those who led armies throughout earlier ages, an essential element of manhood and even more so of warriorhood. Some of Napoleon’s greatest victories were purchased at appalling human cost, but even today few French people think the less of him because of this. The first Duke of Wellington wept when confronted by the ‘butcher’s bills’ for his triumphs, but he never hesitated to sacrifice men to battlefield imperatives. Consider those British squares at Waterloo, which finished the battle where they had started it, but with almost every man dead in his place. Almost one in four of Wellington’s soldiers were killed or wounded on 18 June 1815, about the same proportion of those engaged as fell on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Somme. Great captains have seldom flinched from accepting heavy casualties when circumstances seemed to demand this; their fitness for command would have been questioned had they done so.

In the First World War, the vastness of the struggle imposed an unprecedented scale of loss. But what choice was there before the military leaders, save to stiffen their backs and carry on, unless they chose to resign their posts or concede defeat to the enemy? The literary culture which dominates twenty-first-century perceptions burdens the generals with overwhelming blame for the struggle’s horrors. Yet, on the allied side at least, soldiers bore little or no responsibility for having unleashed Europe’s catastrophe. It is almost impossible to make such officers as led Britain’s forces between 1914 and 1918 appear sympathetic human beings to a twenty-first-century audience, but they were men of their time, and it is thus that they should be judged.

All societies view history through nationalistic prisms, and the British indulge this as much as any, cherishing another persistent myth – that the First World War was much bloodier than the Second. Many people like to believe that in the 1939–45 conflict, Britain suffered much smaller losses because the army had more gifted and humane generals, who declined to sacrifice their men as they had been sacrificed on the Somme and at Passchendaele by such commanders as Sir Herbert Curzon. Yet Paul Fussell, an influential modern writer, was profoundly mistaken when he wrote in The Great War and Modern Memory that the conflict was uniquely awful, and thus lay ‘outside history’, fit matter for literary rather than historical examination. In reality all wars inflict horrors on those who fight them, as well as upon bystanders who find themselves in the path of armies and fall victim to their excesses.

Life and death in Western Europe in the fourteenth century, era of the Hundred Years War and many other struggles, were dreadful indeed, as they were also during the seventeenth-century Thirty Years War, which killed a higher proportion of Europe’s population than perished between 1939 and 1945. It is a childish delusion to suppose that 1914–18’s fighting men experienced worse things than their forebears had known. They did not. For centuries past, soldiers had fought battles in which they were often obliged to stand and face each other’s fire, sometimes at ranges of fifty yards and less, hour upon hour. The hardships they suffered from hunger, weather and disease were quite as severe as those faced by combatants on the Western Front. Survivors of – for instance – Napoleon’s 1812 Russian campaign would have mocked the notion that what men did to each other at Ypres or the Chemin des Dames represented a qualitatively worse experience than their own.

What changed in the First World War was simply that cultured citizen soldiers, disdaining the stoicism displayed since time immemorial by warriors, most of whom were anyway illiterate, chronicled the conflict into which they were plunged with an unprecedented lyricism. Moreover, the absence of significant strategic movement on the Western Front generated a sense of military futility which afterwards extended, understandably but irrationally, and especially among later generations rather than among contemporary participants, to the merits of the allied cause.

Neither the poetic achievement nor the sense of futility were repeated between 1939 and 1945. This is strange, because the second of the twentieth century’s great clashes was much more costly for mankind. Far bloodier attritional clashes were required to accomplish the destruction of Nazism than those on the Western Front in the struggle to defeat the Kaiser. But 1941–45’s principal killing fields, its Sommes and Verduns, lay in the East, and the losses were borne by the Russians, who suffered twenty-seven million dead and inflicted 92 per cent of the German army’s total casualties. The Western allies accepted only a small fraction of the material and human price for destroying Hitler. For four years – between June 1940 and June 1944 – most of the British and later American armies marched and trained at home, while a handful of divisions fought in North Africa, later Italy and the Far East, and a titanic contest in arms took place on the Eastern Front. Only in Normandy, during June and July 1944, did the Western allies go head to head with the Germans in battles during which some units’ losses matched those of 1916.

In the second half of World War II, assisted by a superiority of resources such as Foch and Haig had never enjoyed, together with the fact that the global tide had shifted decisively against the Axis, Britain won some victories under the leadership of competent, if not inspired, generals who were indeed cautious about casualties, to the disgust of their American allies. But it is difficult to argue convincingly that the British commanders of the early war years displayed higher skills than those of French, Haig – and Forester’s Curzon. It is a matter of personal taste whether such generals as Percival at Singapore and Klopper at Tobruk – who surrendered their commands to the enemy in 1942 rather than conduct the sort of sacrificial stands Churchill wanted and Herbert Curzon would have been happy to lead – deserve the applause of posterity for their humanity, or castigation for their ignominious battlefield failure. But the dominant reality of World War II was that Alanbrooke and Marshall, Montgomery and Eisenhower were spared the odium of presiding over bloodbaths comparable with those of 1914–18 not by their own genius, but because the Russians did most of the killing and dying undertaken by British Tommies and French poilus a generation earlier.

It is sometimes suggested that allied generals in Hitler’s war eschewed the sybaritic lifestyle of commanders in the Kaiser’s conflict, who created the legend of ‘château generalship’, champagne-swigging ‘brass hats’ living it up in the rear areas. This view, too, is factually hard to justify. Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten’s South-East Asia Command headquarters in Ceylon was notoriously self-indulgent. Field-Marshal Sir Harold Alexander and his staff in Italy were thought to do themselves remarkably well, as did many of the US Army’s commanders. When champagne was available, most British, American and German generals drank it as enthusiastically between 1939 and 1945 as they did between 1914 and 1918. Soldiers serving in headquarters inevitably live far more comfortably than infantrymen. Once again, modern perceptions have been distorted by the literary culture of 1914–18, which fostered a delusion of the First World War’s exceptionality in this respect, as in many others. Sassoon wrote in one of his most famous poems:

If I were fierce, and bald, and short of breath,

I’d live with scarlet Majors at the Base,

And speed glum heroes up the line to death.

You’d see me with my puffy petulant face,

Guzzling and gulping in the best hotel,

Reading the Roll of Honour. ‘Poor young chap,’

I’d say – ‘I used to know his father well;

Yes, we’ve lost heavily in this last scrap.’

And when the war is done and youth stone dead,

I’d toddle safely home and die – in bed.

Fed by such brilliant derision, the delusion persists that the First World War was unique in its chasm between innocent youth sacrificed in the trenches, and slothful cowards skulking at the rear. In reality, in all wars since 1914, for each rifleman confronting the enemy, at least ten and sometimes twenty officers and men have fulfilled support functions. Every surviving veteran of World War II is today absurdly dubbed a ‘hero’, yet only a small fraction performed any role which put them at greater risk of mortality than they faced in civilian life. Throughout the 1939–45 conflict, Churchill deplored the high proportion of the British Army which never heard a shot fired. It fell to army chief Gen. Sir Alan Brooke repeatedly to rehearse to the prime minister the argument that modern conflict demands a long administrative ‘tail’ for the ‘teeth’ arms. Fighting soldiers of the 1939–45 era liked their brethren who manned office desks and ate hot lunches no more than did Sassoon his ‘scarlet Majors’.

In the pages above, I have deliberately avoided tracing the career of C.S. Forester’s Curzon, because to do so would be to deny readers of this remarkable and compelling novel the pleasure of discovering his history for themselves. My objective has been to set in context the experiences both of the writer and of the character he depicted. Cecil Forester was a friend of my parents whom I met once or twice – a lean, bony, ascetic figure with a twinkling eye which caused him to reflect in everything he wrote his consciousness that the play of human affairs is always a comedy; that we all look equally ridiculous in the bath. It is interesting that Adolf Hitler – a man lacking both cultural judgement and a significant sense of humour – relished the 1937 German edition of The General, and presented specially bound copies to favourites, including Goering and Keitel. He urged them to read the novel, which, he said, offered a penetrating study of the British military caste they would soon meet – and defeat – in battle.

No more than Sir Douglas Haig was Curzon a wicked man, as Germany’s commanders in the Second World War were indeed wicked men, because they colluded in barbarous deeds unrelated to military imperatives. The British generals of 1914–18 did the best they could for their country. They possessed virtues and vices bred into the British military caste over many centuries, but in the unprecedented circumstances of France and Flanders these qualities were tested almost to destruction. It is understandable that today the British people decline to celebrate the 1918 victory of Foch and Haig, because its human cost is deemed to have been disproportionate; but it is irrational that meanwhile they untiringly recall and applaud the 1944–45 triumphs of Eisenhower and Montgomery.

The contrast is explained, if not justified, in part by the fact that it proved necessary to fight and overcome German expansionism a second time in the course of the twentieth century. This caused many people to conclude that the earlier struggle had been a failure, the achievement of victory in 1918 annulled by subsequent events. In some measure, this was true. But a balanced perspective, such as should be attainable a century after the event, suggests that if the Kaiser’s Germany had won the First World War, Europe would have paid a terrible forfeit. It is much too simplistic to look back on the 1939–45 conflict as Britain’s ‘good’ war, and 1914–18 as its ‘bad’ one. The war poets are so often misinterpreted by modern readers, that it is necessary to remind ourselves that Wilfred Owen – to name only the foremost – went to his grave in November 1918 overwhelmed by the horror of his generation’s experience, but unwavering in his conviction that the allied cause was just, and had to be upheld in arms, a view in which some of us remain assured that Owen was right.

A twenty-first-century reader who takes up The General will discover no cause to love Curzon’s kind. But C.S. Forester recognised that his fumbling half-hero was as much a tragic figure as the men whom he led, often to their deaths. The author ends his tale as he began it, with a drollery: ‘And now Lieutenant-General Sir Herbert Curzon and his wife, Lady Emily, are frequently to be seen on the promenade at Bournemouth, he in his bathchair with a plaid rug, she in tweeds striding behind. He smiles his old-maidish smile and his friends are pleased with that distinction, although he plays such bad bridge and is a little inclined to irascibility when the east wind blows.’ A modern reader who wishes to understand something about the nature of the men who directed Britain’s Great War will learn more from the pages of Forester than from those of many modern pundits and novelists, marching doggedly through the centenary of 1914 bearing knapsacks still laden with myths and clichés.

Max Hastings

January 2014