Читать книгу Liberty’s Exiles: The Loss of America and the Remaking of the British Empire. - Maya Jasanoff, Maya Jasanoff - Страница 11

ОглавлениеChapter Two

An Unsettling Peace

ACROSS THE ATLANTIC, when news of Cornwallis’s surrender reached the embattled British prime minister Lord North, he took it “as he would have taken a ball in his breast.” “Oh god! It is all over,” he exclaimed, throwing his arms into the air and pacing frantically about the room.1 He was—at one level—right. Yorktown is conventionally understood as the endpoint of the war. It was the last pitched battle between the British and Continental armies, and led directly to the peace negotiations that resulted in British recognition of American independence.

But as even North must have known, it would take more than surrender to end this war. Beyond America, Britain’s global conflict against France and Spain raged on. Yorktown did not pull back the British forces sweating it out in southern India against French-allied Tipu Sultan. It did not relieve the British soldiers defending Gibraltar and Minorca against the Spanish. Crucially, it did not stop the French fleet that had trapped Cornwallis in Virginia from cruising into the Caribbean and threatening Britain’s valuable sugar islands. Within America, too, hostilities continued to an extent not often appreciated in standard histories of the revolution. The war between Lord Cornwallis and George Washington may have ended in the trenches outside Yorktown, but Thomas Brown’s war was not over, nor was Joseph Brant’s. From the outskirts of New York City to the Florida borderlands, partisan fighting nagged and gnawed at American communities. After Britain ceased offensive operations in January 1782, this was more than ever a civil war, waged by loyalists, patriots, and Indians.

Loyalists responded to news of Yorktown very differently from North. At first, some didn’t even believe it. “A Hand Bill from Jersey of the Surrender of Lord Cornwallis . . . shocks the Town,” wrote New York’s loyalist chief justice William Smith in his diary six days after Yorktown. “I give no Credit to it,” he comfortably concluded, “but suspect an Artifice to prevent the Insurrection of the Loyalists or some Operations on our part.”2 The fifty-three-year-old jurist was a skeptic by nature, which was one reason that he, like Beverley Robinson, had delayed taking a public stand until he was summoned before a patriot committee and forced to choose between swearing allegiance to the republic or moving to British-occupied New York City. When push came to shove, Smith moved to New York. Of course, he quickly recognized the awful truth about Yorktown when veterans arrived in New York bearing eyewitness accounts of the battle and the miserable “Fate of the [loyalist] Refugees left there to the Mercy of the Usurpers.” But as Smith and other influential loyalists saw it, there was still no reason to consider the war over or lost. Smith and his friends concocted various strategies to “balance the Southern Disaster” with further British attacks. “There are 40 Thousand Men . . . here, including Canada and [St.] Augustine,” insisted one, and “if we had made a right Use of them all would have been well, and... there is still no Cause to despair.”3 A somewhat different plan for a troop surge was suggested by John Cruden, the commissioner for sequestered estates in Charleston. Raise an army of ten thousand freed slaves, he said, and America could yet “be conquered with its own force.” Cruden sent the proposal to his patron Lord Dunmore, who enthusiastically forwarded it to General Henry Clinton.4

Even if Britain stopped fighting, loyalists believed that British rule in the colonies could still be saved. Britain could refuse to grant the colonies independence and instead offer them some kind of self-rule, rather like Joseph Galloway’s plan of union, or an analogous proposal by William Smith to create an American parliament.5 This had been the thrust of British peace initiatives during the war, which had granted virtually everything the colonists had requested up to 1775, and even floated the possibility of admitting American representatives into the House of Commons. Though Congress had dismissed the most significant British overture, the Carlisle peace commission of 1778, insisting on independence as a prerequisite for further talks, Smith, Galloway, and others still held out for an imperial federal union.6 Loyalists could perhaps take some comfort in knowing that King George III himself was so strongly opposed to independence that he threatened to abdicate if it were granted. “A separation from America would anihilate the rank in which the British empire stands among European States,” he declared, “and would render my situation in this country below continuing an object to me.”7

Partly because of the range of possibilities still in play after Yorktown, it took a year for British and American negotiators to work out a preliminary peace treaty, and another year until a definitive peace was signed and British troops evacuated. Historians tend to fast-forward through these two years as if their outcome were inevitable. But for loyalists in America, especially those who had already fled to British-occupied cities, these years of peacemaking proved just as stressful as the years of war. Loyalists saw their hopes for a continued British relationship with the colonies dashed, one after another. They wanted renewed military offensives; but Britain declared a cessation of hostilities. They wanted the colonies to remain part of a confederated empire; Britain acknowledged U.S. independence. They wanted protection from reprisals and security of property; the Anglo-American treaty left many feeling just as “abandoned” by the British as the Yorktown loyalists had been. They wanted to preserve the British Empire, and instead they watched the British start to leave. By the middle of 1782, loyalists in British-occupied New York, Charleston, and Savannah confronted urgent choices about where to vest their own futures: in the United States or in other quarters of the British Empire. In a climate of persistent violence and uncertainty, the majority chose to evacuate with the British. Yet the wrenching results of the peace also left them feeling deeply frustrated with the British authorities who brokered it. Loyalists thus often went into exile harboring grievances against the very same government they relied on for support. Their disheartening final months in America laid the groundwork for a recurring pattern of discontent elsewhere in the British Empire, with repercussions as far afield as Nova Scotia, Jamaica, and Sierra Leone.

It was to be as much in European political and diplomatic councils as on a Virginia battlefield that loyalist dreams came crashing down. Back in Westminster, support crumbled for the war effort and the wavering government of Lord North. After all, many Britons had never wanted to go to war in the colonies in the first place. The “friends of America” included some of the greatest politicians of the age, such as the eminent political philosopher Edmund Burke. They also included future leaders William Pitt the Younger, elected to Parliament in 1781 at the tender age of twenty-one, and Charles James Fox, a radical aristocrat, who ostentatiously dressed in buff and blue, the colors of Washington’s army. Though North’s political adversaries had long been stymied by their own internal rifts, the opposition regrouped after Yorktown and emerged determined to bring the war in America to an end.8

Late one February night in 1782, a venerable general rose from the narrow wooden benches of the House of Commons to speak out against a war “marked in the best blood of the empire,” “traced...by the ravaging of towns and the murder of families; by outrages in every corner of America, and by ruin at home.”9 He went on to propose a motion to end “the farther prosecution of the offensive war on the continent of North America, for the purpose of reducing the revolted colonies to obedience by force.” At half past one in the morning, Parliament voted in favor of the motion by a slim margin of nineteen votes.10 Two weeks later, North failed a vote of “no further confidence” (the first use of such a measure in British history) and submitted his resignation.11 In North’s leavetaking meeting with King George III the next day, the king, resistant to the bitter end to the idea of American independence, dismissed his prime minister coldly, saying, “Remember, my Lord, that it is you who desert me, not I you.”12

In June 1782, the new prime minister, William Petty, Earl of Shelburne—another friend of America—took the critical decision to acknowledge American independence. This concession made sense from a metropolitan British perspective, because the future of the thirteen colonies was only part of a larger strategic picture involving France and Spain. It mattered less to Britain whether the United States was independent than whether it remained in a British, as opposed to French, sphere of influence. For loyalists, though, this was the worst news yet, ending any prospect of continued imperial ties. It also raised the next major challenge for administrators. How would the colonial relationship actually be dismantled? This question had two distinct parts. One was addressed in Paris, where British and American peace negotiators began to hash out the details of U.S. independence. There were borders to be drawn. There were economic relationships to be untangled, from trade privileges to the resolution of transatlantic debts. Then there was the issue that most gripped the loyalists’ attention. What provisions would be made to protect them from legal and social reprisals, and compensate them for their confiscated property?

Meanwhile in North America, British officials had to figure out how to phase out Britain’s physical presence on the ground. There were about thirty-five thousand British and Hessian troops to be withdrawn, and substantial British garrisons in three cities—New York, Charleston, and Savannah—to be dismantled. These cities also held at least sixty thousand loyalists and slaves living under British protection, whose welfare had to be taken into account. A further difficulty was that Sir Henry Clinton had resigned his position as commander in chief immediately after Yorktown, leaving nobody actually in charge of superintending this huge task. The job description for his successor was as awe-inspiring as it was unenviable: it required nothing short of deconstructing the apparatus of an empire from the bottom up. Who could be entrusted with it? Fortunately the king and his ministers, despite their many differences, readily agreed on whom to appoint. Sir Guy Carleton, veteran military officer and colonial administrator, was their man.

OF ALL the British officials who influenced the fate of refugee loyalists, Sir Guy Carleton was far and away the most significant, and also the most trusted and well liked. (Lord Dunmore, for instance, who continued to be involved in loyalist affairs, rarely commanded either trust or affection.) As the primary manager of Britain’s evacuation from the United States, Carleton bore the brunt of responsibility for the refugees and slaves under British protection. His actions determined their futures to an extent unrivalled by any other policymaker, and his ideas defined the shape of the loyalist migration in crucial ways. So what sort of a person was the new commander in chief ? Horace Walpole, one of Georgian Britain’s sharpest commentators, estimated Carle ton to be “a grave man, and good officer, and reckoned sensible”—a sight better than any of the ineffectual commanders who had preceded him.13 Many of those who met the general agreed with Walpole’s assessment. Stiff and closed in demeanor, Carleton may well have chilled less commanding souls when he looked down his long, severe nose at them from an imposing height (for the era) of six feet. But if anybody could have glimpsed behind the general’s ungiving façade as he traveled down to Portsmouth on April 1, 1782, and waited for the Ceres to sail to New York, they would surely have detected confidence and at least a whiff of self-congratulation. For Carleton had been to North America before, three memorable times—and this appointment, coming on the heels of a long period in the political wilderness, represented a personal vindication.

Carleton was himself a creation of the British Atlantic world, and his pre-revolutionary experiences in North America shaped the attitudes he brought to his later career. Born outside Londonderry in 1724 into the ranks of the Anglo-Irish landed gentry, Carleton, like so many other boys from ambitious families on the margins of the British Isles, joined the army as a teenager—a path chosen by his brothers as well. He soon became close friends with another officer two years his junior, James Wolfe. While Carleton doggedly served out his lieutenantcy, Wolfe shot up through the ranks, impressing his seniors and fighting in some of the period’s key battles. Soon Carleton’s friend had become his most important patron. In 1758, Wolfe got Carleton appointed quartermaster-general on a campaign the younger man was to command against the French in Canada. They sailed out in 1759—Carleton’s first voyage to North America—and together spent a frustrating summer laying siege to the city of Quebec. In September 1759, Wolfe plotted a daring assault on the fortified capital, hoping to take it by storm. As the morning mist rose on the day of the attack, Carleton stood in the front line of redcoats on the Plains of Abraham, outside the city walls, commanding an elite detachment of grenadiers. By afternoon, he had fallen wounded in the head. His friend Wolfe lay dead. But the battle had been won, and it proved a significant victory indeed. Thanks to the capture of Quebec, the whole of French Canada was ceded to the British Empire in the 1763 Treaty of Paris. In his will, Wolfe left “all books and papers” to Carleton, and a handsome legacy of £1,000.14

Carleton would not figure in the phenomenally popular 1771 painting The Death of General Wolfe produced by the American-born artist Benjamin West, which catapulted Wolfe (and West) to stardom—and Carleton must have felt the loss of his friend’s patronage power at least as much as the loss of his companionship. By then, Carle ton had returned to Quebec as imperial governor and brigadier general. He took up his post within the stone-walled capital almost seven years to the day after he had fought on the battlefield outside it. As he surveyed the city from the windows of the crumbling old Château Saint-Louis, Carleton might have felt he had returned full circle in one further respect. As a colony overwhelmingly composed of white but Catholic, non-Anglophone subjects, Quebec resembled no part of the British Empire so much as his native Ireland. Carleton applied himself to learning French, and to managing the competing interests of the majority French Catholic population (the habitants) and the small but vocal community of Anglophone Protestant merchants. British forms of government “never will produce the same Fruits as at Home,” Carleton decided, “chiefly because it is impossible for the Dignity of the Throne, or Peerage, to be represented in the American Forests.” As such, he systematically supported preserving French systems in place of introducing British laws and institutions “ill adapted to the Genius of the Canadians,” and equally strongly upheld the power of authoritarian direct rule.15 In 1770, he traveled to England to consult with the government on how to reform Canadian administration. These discussions culminated in the Quebec Act of 1774, widely understood as a milestone in British imperial legislative efforts to accommodate culturally and ethnically alien subjects.

Carleton returned to his post later that year, bringing with him a charming new wife—aristocratic, French-educated, and thirty years his junior—their two small sons, and clarified powers under the Quebec Act. While maintaining French civil law and ensuring freedom of worship for Catholics, the Quebec Act also ostensibly protected French Canadian interests by entrusting sole legislative authority to the governor and council. There was to be no elected assembly, no trial by jury, no habeas corpus—measures, according to Carleton, that French Canadians had no wish for. Edmund Burke, among others, condemned the measure as despotic, but as one minister quipped back, “if despotic government is to be trusted in any hands . . . I am persuaded it will be as safe in [Carleton’s] as in anybody’s.”16 Carleton himself, highly satisfied with an act drawn up in large part to his own design, was pleased to find that most Québécois welcomed its terms.17

The trouble was that Anglo-Canadians—to say nothing of British subjects in the thirteen colonies—did not. They saw it as both overly authoritarian and an affront to their own rights and interests. The discontents tearing apart the American colonies to the south soon made their way into the coffee houses of Canada. Reports told of travelers from Boston being intercepted and searched on the roads by Canadian dissidents who were trying to sever communication between British officials. Agents from Massachusetts infiltrated the province to organize antigovernment resistance. A few days after the battles at Lexington and Concord, Anglo-Canadian patriots in Montreal poured black paint over a bust of George III, topped it with a mitre, and hung a rude sign around it reading, “Behold the Pope of Canada or the English Fool.”18 Though the habitants did not rally en masse to the patriots, much to Carleton’s relief, they also appeared unresponsive to his efforts to form a militia for provincial defense.19

Neutrality is all well and good until you get invaded. Ill-equipped, and reluctant to recruit large numbers of Indians (as some British officials encouraged him to do), Carleton had just about managed to fend off guerrilla raids with his limited troops. But in September 1775 the Continental Army invaded Canada, under the command of Generals Benedict Arnold and Richard Montgomery, and sped against the onset of winter toward Quebec. Would it have encouraged or chastened the governor to know that he himself had successfully besieged the city he now endeavored to defend? Before dawn on the last day of 1775, the hungry, half-frozen Americans assaulted the city with a stinging blizzard blowing at their backs. By the time the late sun curved into the sky, it was all over. As in 1759, the leading attackers had fallen outside the walls: Arnold with his left leg shattered, Montgomery dead in the snow. But the American painter John Trumbull’s attempt to immortalize the episode with The Death of General Montgomery enjoyed less success than his teacher Benjamin West’s depiction of Wolfe. Because this time it was Quebec’s defenders who won, securing the province in the British Empire. Years later, Carleton would find himself lending the lamed Arnold a supportive arm, as the American limped into his first audience with the king.20

With the American invasion repelled, and the habitants having rejected a diplomatic overture from Congress to join the revolution, Carleton launched a counteroffensive into New York. In October 1776 he smashed the patriots at Lake Champlain and joined forces with Burgoyne. But, seeing “the severe season approaching very fast,” he withdrew into Canada for the winter.21 Burgoyne and others chastised him for not proceeding farther south to Fort Ticonderoga, a fatal blunder (they said) that allowed the Americans to get away. Whether or not they were right, the decision proved fatal for Carleton’s career. He had already made an enemy out of the influential colonial secretary Lord George Germain. Fortified by Burgoyne’s hostile reports, Germain fired Carleton from his military command and tried to recall him from the governorship. Carleton preemptively resigned his positions in 1777 and returned to England in disgust.

His sixth Atlantic crossing carried him toward an uncertain future, his reputation tarnished and position reduced. Yet leaving North America ultimately put Carleton in the most advantageous situation he could have hoped for. One by one British generals fell in America, while Sir Guy and Lady Maria, comfortably distant from a badly managed war, made the rounds of London society, cementing their connections among the British elite. Carleton, without knowing it, had also landed in a fortunate political position. His abilities had made him an enduring favorite of the king, and now his feud with Germain endeared him to the parliamentary opposition as well. The appointment as commander in chief of British forces in North America offered an especially sweet satisfaction after his earlier dismissal from military command. And it must have been even better to know that his rehabilitation had helped force his hated rival Germain out of office.22

So as he faced America again in the spring of 1782, Sir Guy had much to reminisce about. But it was time to confront the challenges ahead. He cracked open the seal on his instructions from the prime minister and read about his mission. The most “immediate object to which all other considerations must give way” sounded deceptively simple: Carleton was to withdraw “the garrison, artillery, provisions, stores of all kinds, every species of public property” from New York, Charleston, and Savannah, as well as St. Augustine in East Florida if he saw fit. Meanwhile, in his role as a peace commissioner, he was to placate the Americans as much as possible in order “to revive old affections and extinguish late jealousies”—part of a hearts-and-minds offensive designed to separate the Americans from the French. There was one group of people who were to command his closest attention. Carleton must extend his “tenderest and most honourable care” to the loyalists, by helping them move to “whatever other parts of America in His Majesty’s possession they choose to settle.”23

The mission was defined clearly in outline, but executing it would be daunting indeed. He had up to 100,000 soldiers and civilians in British-held cities to evacuate. Yet he possessed scant resources with which to provision them, no clear instructions on where actually to send them, and fewer than fifty ships at his disposal. And for all that hostilities had officially ceased, Carleton discovered a different reality on the ground. From New York to the swamps and forests of the lower south, the civil war continued, clouding over the impending evacuations with violence.

TO RECOVER the conflicts that continued in America during the months after Yorktown is to understand the passion with which some loyalists clung to, and fought for, their version of British America. Equally important, it helps explain why so many loyalists chose to follow the departing British. Wartime violence had pushed thousands of loyalists into British lines, for what they hoped would be a temporary stay. But as internecine conflict continued into peacetime, present danger and the threat of future reprisals made loyalists fear for their long-term welfare in the United States. It transformed their displacement into an international diaspora.

Carleton landed in New York on May 5, 1782, to find himself immediately swept up in a controversy that revealed the depth of factional animosity still raging in the colonies. It centered in part around one of New York’s leading loyalists, William Franklin, the last royal governor of New Jersey, and the only son of patriot statesman Benjamin Franklin. How long ago it seemed that father and son had flown a kite together, the wet string twirling and pulling in William’s hands as the square of stretched silk bobbed, fluttered, and caught the currents up toward the storm clouds. For thirty years the Franklins had been close partners in life and work, moving together to London and back and sharing in the early upbringing of William’s son, Temple. But the coming of war opened an unbridgeable rift between them. Benjamin Franklin broke with British authority, signed the Declaration of Independence, and moved to Paris, where he now served as a peace commissioner and one of the United States’ most revered public figures. William Franklin, though no friend to arbitrary power, and a champion of imperial reform, could not bring himself to renounce his loyalty to the king—and endured two years as a patriot prisoner for his refusal. During his time in jail, his beloved wife Elizabeth fell dangerously ill, but Washington denied Franklin permission to visit her. She “died of a broken heart” before her husband could see her. Equally painful for William, Benjamin had essentially adopted Temple Franklin as his own and taken the lad to Paris, where Temple acted as secretary to the American peace commission. The relationship between Benjamin and William Franklin would never be restored, and stands out as the highest-profile example of how this civil war tore families apart.24

William Franklin arrived in New York City after his release from jail, battered, disappointed, and ready to fight back. His efforts to organize loyalists were formalized in 1780 with the creation of a so-called Board of Associated Loyalists, which sponsored paramilitary “companies of safety”—a counterpart to patriot committees of safety—to protect loyalists in the hinterland.25 Under the board’s patronage, partisan fighting ravaged the greater New York area well after Yorktown. On an early spring day in 1782, a patriot captain named Joshua Huddy, notorious for his rampages through central New Jersey, was found swinging from a tree at Sandy Hook. A paper pinned to his chest declared, “We, the Refugees, have with grief long beheld the cruel murders of our brethren, and . . . determine to hang man for man, as long as a refugee is left existing. . . . UP GOES HUDDY FOR PHILIP WHITE.” A loyalist captain had ordered the execution—apparently on William Franklin’s instructions—in retaliation for the summary killing of another loyalist, Philip White, some days earlier. Outraged by the incident, George Washington demanded that the perpetrator be handed over for punishment or else he would order a British prisoner of war executed in his stead. To make matters worse, the officer selected for American retribution—a Yorktown prisoner—turned out to be the poignantly young and impressively well-connected Charles Asgill, heir to a baronetcy. Before long the New York spat had become an international incident, with Prime Minister Shelburne asking Benjamin Franklin to intercede personally on Asgill’s behalf.26

When the new commander in chief arrived in New York City, patriots were screaming for justice, loyalists were up in arms to protect their own, and British regulars were incensed at the idea of an innocent officer falling victim to Washington’s lex talionis. On his very first day on shore, Carleton spent two hours closeted with William Franklin and William Smith discussing the case. Asgill was ultimately relieved thanks to a direct appeal from his mother to a different American ally, Queen Marie Antoinette. Washington did not come out well from the affair: his unforgiving stance verged on downright cruelty. But William Franklin came out looking worse. As the sordid details of the case emerged before boards of inquiry and a court-martial, Franklin appeared vengeful and injudicious, denting his reputation as a sage leader. It was a thoroughly souring experience for the former governor. The news, which reached America in midsummer 1782, that Britain had agreed to recognize American independence—that Franklin’s father had won—only compounded his despair. In August 1782, William Franklin sailed to England for a life in exile, carrying with him—“for a Pretext,” thought William Smith—“a Petition to the King from the Loyalists, deprecating the Separation of the Empire and imploring Protection,” a list of grievances against the government whose asylum he sought.27

The Asgill affair was just the first instance of the violence still haunting America that Carleton had to contend with. On the western edges of New York and Pennsylvania, Britain’s Indian allies had been caught up in another ongoing partisan struggle. After Saratoga, Molly Brant had moved to Niagara with the other Mohawks from her village. Like many a refugee, she found herself “not at all reconciled to this place & Country,” for it “at first seemed very hard for her to leave her old Mother . . . & friends behind and live in a Country she was an entire Stranger in.”28 Still, she continued to muster support for the British, and was rewarded in turn with a house built for her on Carleton Island, at the far eastern tip of Lake Ontario. Joseph Brant fought in an intensifying series of offensives and counteroffensives: patriots led a scorched-earth campaign across the Finger Lakes region; Indian war parties and loyalist militias swooped down on patriot outposts ranging all the way from the Mohawk to the Ohio rivers.29 Brant’s raids in one month alone resulted in ninety people captured and killed, more than a hundred houses destroyed, and five hundred cattle and horses seized.30 Such vicious frontier war attested to an animosity between white colonists and Indians too entrenched for a formal Anglo-American cease-fire to eliminate. These hatreds boiled over in what was probably the largest massacre of civilians during the entire American Revolution, five months after Yorktown. In far western Pennsylvania, patriots captured a village of pacifist Moravian Delaware Indians and methodically murdered every one, striking each male victim first with a blow to the head, as livestock were stunned before slaughter, then tearing off their scalps.31 Carleton’s ability to neutralize frontier violence would have special bearing on the future of the refugee Mohawks.

Of all the theaters of continuing conflict, however, the fiercest was also the one of most immediate importance to Carleton. In the deep south, loyalists fought desperately to preserve British power. William Johnston and his father-in-law John Lichtenstein remained at the forefront of these efforts, by commanding cavalry brigades that patrolled the swampy outskirts of Savannah. Two weeks after Yorktown, Johnston and his men were relaxing at their base when they saw three hundred patriots advance from the woods. Rapidly surrounded—and doubtless not eager to follow the fate of his brother Andrew, slain at Augusta—Johnston was on the verge of surrendering his sword to the opposing commander when a patriot soldier struck out at one of Johnston’s men. Fired up by the insult, Johnston promptly began a vigorous defense of their position. Fortunately the outnumbered loyalists were soon rescued by a detachment of Thomas Brown’s Rangers, commanded by a Johnston family friend named William Wylly.32

Johnston’s brush with death was just one of many such episodes in the southern civil war. “The rage between Whig and Tory ran so high, that what was called a Georgia parole, and to be shot, were synonyms,” recalled one American officer.33 Patriots and loyalists struck truces that held only as long as tempers. Brown may never have embraced his reputation for savagery, but another loyalist officer described with positive pride how he ranged through the Carolina borderlands burning his enemy’s houses, stringing up deserters from trees, taking hostages, and stealing slaves and horses.34 All this fighting left the Carolina and Georgia backcountry “so completely chequered by the different parties” that no livestock, not even any squirrels or songbirds, animated the land; just the bald, red-headed turkey vultures, tearing at the corpses.35 In the spring of 1782, American forces encamped a few miles outside Savannah, busily fomenting desertion from the British ranks. Thomas Brown sortied from the city, intending to link up with three hundred Indian allies and drive the Americans back. But Brown failed to make the connection and his skirmish ended in stalemate. A few weeks later, the Indians were also rebuffed and the surviving warriors streamed into the safety of British lines. The struggle to save British rule in Georgia was over.36

This was the backdrop against which Carleton set in motion a momentous train of events: the evacuations of British-held Savannah and Charleston. Carleton saw this step as “not a matter of choice, but a deplorable necessity in consequence of an unsuccessful war.”37 There simply were not enough British troops to hold these cities, let alone send badly needed reinforcements to the Caribbean. In early June, 1782, a letter from Carleton marked “Secret” reached British headquarters in Charleston. “A day or two after the receipt of this letter,” it warned the commanding officer Alexander Leslie, “you may expect off the bar of Charles-Town a fleet of Transports: these I send for the evacuation of Savannah, and of St. Augustine; to bring off not only the Troops, with the Military and public Stores of all sorts; but the loyalists who choose to depart with their effects.”38 General Leslie immediately forwarded the news to Savannah, asking Georgia governor Sir James Wright to notify “the King[’s] Loyal subjects . . . to provide for whose ease and accommodation on this distressing occasion . . . has been an object of prime consideration with the Commander-in-Chief.”39 Two months later Leslie faced exactly the same task when he was ordered to evacuate Charleston.

What looked like a strategic necessity to Carleton looked like a disaster to the thousands of loyalists in both cities. News of evacuation prompted outcry and anguish. A mere five hundred more troops, Governor Wright believed, could “have drove the Rebels entirely out of the Province.”40 Yet instead the British were abandoning it. “The distress and misery brought on His Majesty’s Loyal Subjects here, you cannot conceive,” Wright reported, “and the very great property given up...I apprehend your Excellency has no idea of.”41 In Charleston, a handbill authored by a self-styled “Citizen” (not, notably, a “subject” of the British crown) wryly proposed various ways loyalists might try to curry favor with the incoming patriots:

[O]ne man intreats his wife or some friend to write letters intercessory for him;—then, there is another person has a cousin of his wife’s aunt now in the American camp;...and last of all, one pleases himself with the charming thought, that he was always a friend to the American cause in his heart—though perhaps he now and then does duty at the City Guard in a Red Coat.42

But British withdrawal was no jesting matter for most loyalists. They heard terrifying reports of what was happening outside the city limits, of loyalists hunted down and murdered by vindictive patriots.43 Confiscation acts passed by the Georgia and South Carolina patriot legislatures in 1782 expelled some five hundred prominent loyalists as traitors on pain of death, taking their property, and subjecting “divers other persons” who “did . . . traiterously assist abet and Participate in . . . treasonable Practices” to similar penalties.44 And when delegations of loyalist merchants went to meet with patriot authorities to find out what treatment they might expect if they stayed on, the answers were far from encouraging. Savannah loyalists were told they could take “reasonable time . . . to dispose of their property and settle their pecuniary concerns,” but that the Continental Army could not promise total protection, and of course “traitors” (vaguely defined) could always be prosecuted under the Confiscation and Banishment Act.45 Similar terms in South Carolina convinced Charleston merchants that the patriots were “retaliating upon & punishing the innocent.”46 Prospects hardly seemed any brighter for the hundreds of humbler refugees, such as those dwelling in Charleston’s makeshift camp of “miserable huts.” Eight hundred “distressed refugees” were dependent on cash handouts from the British army, and had scant hopes of finding much better if they returned to their war-ravaged homes.47

What were they to do? Here was a country coming out of civil war, with the possibility of anti-loyalist reprisals, and the good chance that their property had been seized or destroyed in their absence. There were the British ships, offering free passage to fresh domains. Amid so much confusion, one thing at least was clear. Loyalists who left would enjoy the security of remaining in the British Empire. Within a matter of weeks of the evacuation orders, the majority of civilians in Savannah and Charleston made up their minds to go.

In the twenty-first century, such scenes of mass human displacement, of cities emptying out, have come to seem depressingly common consequences of war. But in the 1780s there were simply no British precedents for civilian evacuations on this scale. Nor have any histories of the American Revolution described the British withdrawals in detail. Yet what unfolded on the ground during the last months of British power in America held up a startling mirror to the familiar images of United States nation-making. For while American patriots considered how to fashion the thirteen colonies into a United States of America, following Thomas Paine’s injunction to “begin the world over again,” thousands of refugees set off into the British Empire, as one loyalist put it, “to begin the world anew.”48

SO WHERE would they go? For many white loyalists in Savannah and Charleston, the choice of destination hinged on one overriding consideration to do with a very special kind of property, at once portable, valuable, and alive: slaves. The question of how best loyalists might sell or employ their slaves crucially influenced decisions about whether and where to go into exile. During the war, most refugees who had left the colonies had traveled to Britain or Nova Scotia. But in Britain, slaveowning had been effectively illegal since the early 1770s, while Nova Scotia, a preferred locale for New England and New York refugees, was seen as climatically unsuitable for southern plantation slaves. Jamaica and other British West Indian islands seemed a better option, but these well-settled islands had little uncultivated land available, and were known for their high cost of living and high chance of dying of tropical disease.

That left only one British territory as an attractive possibility for southern slaveowners: the neighboring loyal province of East Florida. More or less similar to Georgia in climate and ecology, and unfolding in mile upon mile of uncultivated land, East Florida appeared to loyalist planters like the last best hope for reproducing their existing lifestyles. The ambitious governor of East Florida, Patrick Tonyn, enthusiastically encouraged loyalist immigration. “Upon the unfortunate defeat of Earl Cornwallis” he issued a proclamation inviting “the distressed and persecuted Loyalists in the neighbouring Colonies” to “become settlers in this Province.”49 Hundreds had already arrived. The only trouble was that in Carleton’s initial orders, St. Augustine had also been slated for evacuation. Dismayed loyalists and sympathetic officials chorused in protest against the measure, as did Governors Wright and Tonyn.50 Under loyalist pressure, Carleton canceled the evacuation on the grounds that Florida would give loyalists “a convenient refuge, whither the most valuable of their property may without much difficulty be transported, and in a Country where their Negroes may continue to be useful to them.”51 East Florida henceforth became the destination of choice for southern loyalists—underscoring the importance of property concerns, and slavery in particular, in determining the course of the loyalist exodus.

Loyalists in Savannah were the first to confront a situation that would be replayed on successively larger stages in the months ahead. Seven thousand white civilians and slaves prepared to depart in less than four weeks’ time. How or if loyalists readied themselves psychologically for leaving can never be really known, but there were concrete chores aplenty. The city’s neat grid of angles and squares turned into a moving mosaic. Days became busy with selling and packing, transactions and farewells. Soldiers piled up military stores and ordnance below the fort walls to be rowed out to the coast. Slaves hauled furniture and baggage and gathered by the hundreds to ship out with their masters. Ultimately almost all of the five thousand enslaved blacks in Savannah would leave, transported from the city as loyalist property. On July 11, 1782, the garrison trooped into flatboats and rowed around the grassy curves of the river mouth to the sea. “Nothing can surpass the sorrow which many of the inhabitants expressed at our departure,” a New York soldier noted in his diary, “especially those ladies whose sweethearts were under necessity of quiting the town at our evacuation; some of those ladies were converted and brought over to the faith, so as to quit as well and follow us.”52

If it is hard to know just what went through the minds of departing loyalists, it is especially difficult to gain insight into the attitudes of the majority of people who left, those five thousand or so enslaved blacks, who outnumbered the white migrants by more than two to one. George Liele, though, part of the tiny minority of free blacks to evacuate, did provide some account of what made him go. Liele may have found a higher solace in his journey, for he followed two masters to the seafront—if you counted the one in heaven as well as the one on earth. For about three years, Liele had been living in Savannah as a free man, ever since his former owner, a loyalist who had manumitted him before the war, had been killed, his hand blown off by a patriot bullet. Liele may well have worked in Savannah as a carter, like many other free blacks, helping to provision the British as his friend David George was doing from his butcher’s stall. But the labor that really consumed Liele (and George) was the Lord’s: preaching among the blacks in town, as he had done in the cornfields, clearings, and barns around Silver Bluff. Though David George moved his family to Charleston in anticipation of disruptions in Savannah, Liele stayed on and preached till the very end of the British occupation.

Freedom, Liele had learned, could be a precarious condition. Once, he had been jailed by whites who did not believe his old master had really freed him. Only by presenting his manumission papers did he get released, with the support of a white benefactor, a backcountry planter and loyalist officer called Moses Kirkland. (It was Kirkland who had taken in Thomas Brown after the latter’s torture in 1775.) Liele owed Kirkland something more. Liele’s wife and four small children had all been born slaves, and Kirkland apparently helped him purchase their freedom. In return, Liele agreed to renounce a portion of his own liberty by indenturing himself to Kirkland for a period of a few years. Now the British were leaving Savannah, Kirkland was banished, and George Liele was “partly obliged” to follow, no longer a slave, and yet neither entirely free. Like everyone else, he had important preparations to make before his departure. Standing in the shallows of the Savannah River in the shadow of the city walls, Liele baptized Andrew, Hannah, and little Hagar Bryan, three slaves belonging to a loyal Baptist, bringing three new members into the church. As the Lord willed that Brother George would carry the word beyond American shores, now it was for Brother Andrew to continue his work among Georgia blacks.53

On July 20, 1782, Liele and his family sailed on the first convoy out of Savannah, bound for Port Royal, Jamaica.54 His reason for evacuating with the British might seem clear—to protect some limited freedom for himself and his family. But the moment Liele stepped on board he would have seen overwhelming evidence of why so many whites left: to protect their enslaved property. The sloop Zebra (a suggestive name given the racial breakdown of its passengers) and its twelve flanking ships carried a mere fifty white loyalists on board. The vast majority of its passengers were nineteen hundred blacks, almost all of them slaves.55 Whole slave communities sailed out together: more than two hundred belonged to governor Sir James Wright alone, the remnant of an enslaved labor force numbering more than five hundred souls that Wright had once put to work across eleven plantations. They had survived the war only to be transported to Jamaica in the custody of one of Wright’s associates, Nathaniel Hall, there to be hired or sold into the notoriously punishing conditions of Caribbean slavery.56

The next day, a second evacuation fleet left for St. Augustine. This convoy would also be numerically dominated by slaves; Georgia’s lieutenant governor John Graham took charge of no fewer than 465 black men, women, and children belonging to himself and others.57 Thomas Brown, meanwhile, escorted another, more unusual nonwhite contingent. About two hundred of the Creek and Choctaw warriors who had fought with him against the patriots were returning to their villages, after spending a year at war.58 Their presence on board represented a rare British concession to southern Indian allies, and a unique counter-flow within the exodus: for them, and them alone, this voyage out was a voyage home. The St. Augustine convoy also carried most of William Johnston’s extended family: his father Lewis Johnston Sr., his brother Lewis Jr., and his sisters with their husbands and children. The Johnstons had a strong reason to favor Florida. With seventy-one enslaved men, women, and children in his household, Lewis Johnston Sr. figured as one of the largest slaveowners among the Georgia refugees.

Elizabeth and William Johnston, though, joined the fleet bound for Charleston with William’s regiment. It was an unusual choice for Elizabeth to go to Charleston with William, rather than to St. Augustine with her in-laws—not least because she was then seven months pregnant, and passed up the offer from a patriot friend of William’s to stay in Savannah under his protection until she was “fitter for moving.” But the Johnstons had already been apart for much of their short married life, and Elizabeth wanted no more of it. She had suffered the loneliness of raising their firstborn son, Andrew—a “handsome sweet fellow” with a “large proportion” of his father’s “passionate temper”—while William was away at war. And she had acquired another reason to wish William close at hand. For beyond her watch, William had fallen into his old habit of gambling, “a vice so destructive and ruinous in its nature” that it threatened to wreck their growing family.59 He did not reveal the alarming extent of his losses to his wife, but wrote to her father with hangdog contrition, imploring Lichtenstein to support the family in their need.60 What was worse, William’s behavior opened a rift with his own father and sisters. “You know not how wretched you have made me,” Elizabeth opined, “and tis cruel to distress a Father whose sole wish & care, is to see his children happy.”61 Dr. Lewis Johnston, with his wealth and influential connections, was not a man to be alienated lightly. A rift with him would cut off the young couple from their best source of support and patronage.

So when British power collapsed around her in Savannah, Elizabeth Johnston followed her impulse and her spouse: “My husband would not like the separation, and I positively refused to remain.” Not once did she mention the issues of principle involved in leaving her home. Nor, more strikingly, did she note the obvious impetus for her extended family’s departure. Every single one of Johnston’s close male relations had been proscribed under the Georgia Confiscation and Banishment Act, including William Johnston, his father Lewis, and her father John Lichtenstein. In her own telling, Johnston did not leave for reasons of political sentiment but for emotional ones, the bond of conjugal love.

The Johnstons arrived in Charleston to find that city, too, in the throes of pre-evacuation mayhem. Day in, day out, British officials coped with shortages of food, rum, ships, and cash; rising disorder and falling morale; and more than ten thousand civilians clamoring for relief and reassurance. “The perplexity of civil matters here is so much beyond my abilities to arrange, that I declare myself unequal to the task, nor have I the constitution to stand it, from morning till night I have memorials and petitions full of distress, &c. &c. before me,” moaned Charleston commander General Leslie.62 Patriot advances had cut off the city’s food supply, forcing Leslie to send forage parties out to raid the countryside for grain.63 Soldiers grew restless and undisciplined, falling “into all kinds of dissipation,” and, increasingly, running away.64 An attempted deserter was hanged before a crowd of two thousand; two other men were flogged with “500 lashes each at the most public parts of the town and then drummed out of the garrison, for harboring two deserters.”65 Conditions among the impoverished refugees were not much kinder. From November 1781 to November 1782, a neighborhood coffin maker crafted 213 wooden boxes for the loyal dead: a poignant list of spouses, grandparents, and, especially, children; for a teenager named “America,” and for individuals of whom no more was recorded than their heights.66

Within a week of the publication of evacuation orders in August, 1782, 4,230 white loyalists announced their intention to depart with the British, along with 7,163 blacks, chiefly slaves.67 Following the Savannah precedent, East Florida was the destination of choice. But in Charleston, a far larger and more economically developed city than Savannah, the evacuation of so many slaves posed special complications.

During the British occupation, about a hundred patriot-owned estates with five thousand slaves had been “sequestered” and run for the benefit of the British military by the loyalist commissioner of sequestered estates, John Cruden. Now, with evacuation imminent, many loyalists whose own slaves had been seized by the patriots wanted to take sequestered slaves as compensation. Logical though the swap might appear, it was also illegal, since loyalists had no title to these patriot-owned slaves. To make matters more difficult, hundreds of black loyalists lived and worked in Charleston—David George and his family now among them—who had legitimate claims to leave with the British as free people. Patriots balked at the prospect of any of their valuable slaves, sequestered or freed, sailing off into the empire. How could Britain evacuate blacks so as to prevent wrongful seizure of patriot-owned slaves, on the one hand, while upholding promises of freedom to black loyalists on the other? Leslie wrote to Carleton for instructions. “In whatever manner we may dispose of such of them who were taken on the sequestered estates,” he felt, “those who have voluntarily come in, under the faith of our protection, cannot in justice be abandoned to the merciless resentment of their former masters.”68 Carleton emphatically agreed: “Such as have been promised their freedom, must have it.”69

With loyalists and patriots clamoring for fair allocation of property, and blacks both free and enslaved facing him with their plight, Commissioner John Cruden had his hands full and his capacities stretched. Not least, Cruden was terribly in debt: numerous people had failed to pay him for hired labor and produce from the sequestered estates, and his public accounts were £10,000 in arrears.70 (He and his younger brother had meanwhile racked up such personal expenses that their poor father, a Presbyterian minister in London, had asked his brokers to stop extending the boys credit.)71 But John Cruden had always been one to see the bright side of things—witness the proposal he had sent to his patron Lord Dunmore, after Yorktown, to raise an army of free blacks and continue the war. When provisions were running low in Charleston in the summer of 1782, Cruden equipped a flotilla of galleys and dispatched them into Low Country waterways to seize patriot grain supplies.72 In the months ahead Cruden would do whatever he could to ease loyalists’ distress—even when his ideas and methods became unconventional indeed.

Cruden prided himself on his management of the sequestered estates, many of which he averred were “in higher Cultivation than when I took them into my Charge, [and] would have been torn to pieces by needy Creditors” without his care. Surely, he thought, it would be simple enough to resolve disputes over slaves. Putting forward his own version of the golden rule, he endeavored to return all sequestered slaves to their patriot owners “in the hope & firm belief that it will produce a similar effect on them by Exerting them to restore the property of the British Subjects.”73 Cruden thus vigilantly policed loyalists from taking away patriot-owned slaves that did not belong to them. He trusted patriots to be equally respectful, in turn, of loyalist property and the freedom of black loyalists. To him there was no contradiction between upholding the rights of slaveowners in one domain and supporting the liberty of free blacks in another: that was what honor was all about.

As the first ships prepared to sail from Charleston in October 1782, Leslie and the patriot governor of South Carolina agreed on terms respecting the exchange of prisoners and the transfer of sequestered property. “All the Slaves, the Property of American Subjects in South Carolina, now in my Power, shall be left here, and restored to their former Owners,” ordered Leslie, “except such Slaves as may have rendered themselves particularly obnoxious by their Attachment and Services to the British Troops, and such as have had specifick Promises of Freedom.” To placate the patriots and “in order to prevent the great Loss of Property, and probably the Ruin of many Families,” he volunteered to pay a fair price for black loyalists whose former owners contested their cases.74 But the enormous numbers of blacks claiming freedom as loyalists made Leslie blanch at the “monstrous expense” that would be involved.75 Instead, Leslie appointed a board of inspectors to interrogate blacks who had “come in under the faith of various Proclamations and promises, in hope of obtaining their freedom,” and judge their veracity.76 American inspectors were given the right to search outbound ships for illicitly removed slaves. Leslie’s handling of this issue provided an important model for the still larger evacuation of blacks that Sir Guy Carleton would soon superintend in New York.

David George and his family were among those whose freedom was confirmed by the board, and numbered among an estimated fifteen hundred free blacks evacuated from Charleston.77 George was impressed to discover that his family, just like the white refugees, was entitled to free passage to other British domains. They sailed on one of the first convoys out of Charleston, at about the beginning of November 1782.78 Though the majority of ships were bound for New York or St. Augustine, the Georges had a more unusual destination. They and their five hundred or so fellow passengers were headed for Nova Scotia, where they would be among the first of thousands of loyalist refugees who flooded into the British North American province in the year ahead.79

Coincidentally, William Johnston may have been one of the officers who cleared George for departure. As one of eleven men appointed to Leslie’s board of inspectors, William spent some of his last days in Charleston hearing out the stories of black women and men who had fled from slavery. Elizabeth Johnston gave birth to the couple’s first daughter, Catherine, in the comfort of a stately sequestered house. Around her in the emptying city, “everything is in motion, and turned topsy-turvy.” “It is impossible to describe what confusion, people of all denominations, seem to be in,” one soldier noted. “The one is buying everything he can to complete his stock of goods, the second is searching for a passage to some other garrison of His Majesty’s troops; the third is going from house to house to collect his debts.”80 Though the Johnstons had no property to handle in Charleston, they also faced fresh choices. William’s regiment was due to ship out to New York City, along with most of the Charleston garrison. Far away and likely facing imminent evacuation itself, New York made little sense as a destination for Elizabeth and the children. This time they decided that she would head for St. Augustine separately and stay with William’s relatives until he could join them there, to establish their first real family home.81

In early December 1782, Elizabeth Johnston stepped into a small boat with her toddler son, infant daughter, and a black nurse, and rowed out into the harbor to board a Florida-bound schooner. It was like cruising into a jigsaw puzzle. Above her loomed the curved wooden walls of a city afloat, dark with slime and tar, the outlines of figures scurrying along decks and rigging, canvas sails stretched on a lattice of masts. Skiffs and rowboats traced ripples across the water, ferrying loyalists and slaves, barrels of food and supplies, furniture and livestock—even the valuable bells of St. Michael’s Church—to the waiting ships.82 More than twelve hundred white loyalists and twenty-six hundred blacks plashed out to join a convoy bound for Jamaica. Another group of two hundred black loyalist soldiers gathered to sail for Saint Lucia. A few hundred individuals, including various government officials, joined a convoy for Britain. Finally, on the afternoon of December 12, the soldiers began assembling on the city wharfs to board the transports for New York. Two days later, the Americans formally reoccupied Charleston, while the Johnstons swayed out to sea in opposite directions: he with the garrison to New York City, she to join the rapidly growing loyalist community in East Florida.83

Together, the evacuations of Savannah and Charleston set more than twenty thousand loyalists, slaves, and soldiers on the move: so many people separated, so much left behind, so many lives bent on unpredictable routes. What unfolded during these evacuations exposed contradictions that would follow the refugees into exile. Loyalists left for reasons of pique as much as principle, primed to find fault with the administrators they nonetheless relied on. Free blacks and slaves traveled on the same ships, leaving their status open to confusion and abuse. The Johnstons and the Georges, who had been evacuated twice, pointed to another recurring phenomenon: many of these refugees would end up moving again and again. Yet for all that their emigration, with its many uncertainties, could make loyalists worry about the worst, it could also promise change for the better—a chance to rebuild fresh lives as British imperial subjects. Though less frequently voiced than anxieties and laments, some refugees offered more optimistic assessments of evacuation. Out of so much loss, one might find something new. That was how John Cruden saw things when he sailed for St. Augustine, his dreaming not yet done. “This moment,” he felt, was “perhaps the most important the World Ever beheld.”84 And what was the value of being on earth at such a time as this, if not to capitalize on its opportunities?

AS THE SHIPS sailed out of Charleston, one year after Yorktown, loyalists had come to terms with the reality of defeat and begun, literally, to move on. The war was over, U.S. independence assured. At least eight thousand white and black refugees had already settled in other British colonies, notably East Florida. But there were still some loyalist hopes hanging in the balance. What would the United States provide for loyalists by way of protection against retaliation and compensation for their losses? It was up to the peace commissioners in Paris to hash out the answers, which would have great bearing on the decisions of loyalists still uncertain about whether to stay or go.

The terms of Anglo-American peace rested in the hands of a mere five men, each of whose personal attitudes would carry significant weight. The seniormost member of the American peace commission was Benjamin Franklin, who was joined in Paris by the New York lawyer John Jay and John Adams of Massachusetts. A fourth American commissioner, South Carolina planter Henry Laurens, would come to meet them later. The British side in the negotiations was superintended by just one man, Richard Oswald, appointed to the post by the prime minister, Lord Shelburne. Oswald had striking, not to say surprising, credentials for the job. Nearly eighty years old, the Glasgow-based merchant had built a fortune in the Atlantic trade, primarily shipping tobacco to Britain from the Chesapeake and slaves to America from a trading fort he and his associates owned on Bunce Island, in Sierra Leone. Oswald had invested significantly in East Florida land. Above all, he had many close American friends, including Franklin and Laurens. Indeed he was so much a “friend of America,” in this sense, that many did not think he could be trusted to speak loudly enough for British interests. Other government ministers sent a deputy to keep tabs on him, Henry Strachey, a deft civil servant who had cut his teeth as secretary to East India Company commander Robert Clive, and who, like Oswald, owned a sprawling estate in East Florida and had close ties with Laurens.85

In hotel suites, over dinner tables, and in letters crisscrossing the quarters of Paris, the negotiators wrangled over how to disentangle the thirteen colonies from the British Empire. By the late fall of 1782, only a few sticking points remained. Americans wanted access to the codrich shores of Newfoundland, and to clarify the western and northern boundaries of the United States. Many Americans owed money to British creditors, and there was some debate over how these debts should be resolved. But the most nagging outstanding question concerned the loyalists: what, if anything, would the United States do to compensate them? Bit by bit solutions were brokered. Oswald conceded the fishing rights. The two sides agreed to mark the western border of the United States at the Mississippi River. John Adams then helpfully observed that the question of debts should be treated separately from the question of loyalist property—a decision that “struck Mr. Strachey with peculiar pleasure; I saw it instantly smiling in every line of his face”—and insisted, as a point of Yankee honor, that all American prewar debts be paid.86

That left the loyalists. Moral responsibility aside, Lord Shelburne and his ministers knew that failing to secure concessions for the loyalists would open them up to attack from their political opponents, and he instructed Oswald and Strachey to take the issue seriously.87 But as they sat down to negotiate this last point—the only diplomatic obstacle left between war and peace—they may not have realized what firm resistance they would face in one of their American counterparts. Benjamin Franklin adamantly opposed granting anything to the loyalists. Even Jay and Adams were surprised by Franklin’s passion on the subject: “Dr. Franklin is very staunch against the Tories, more decided on this point than Mr. Jay or myself,” Adams noted.88 And as the weeks wore on, Franklin’s resolve seemed only to harden. If Britain demanded compensation for loyalist property, Franklin threatened, then he would demand that Britain pay reparations to the United States for all the damages of war. Loyalists had spent years “wantonly burning and destroying farm houses, villages, towns,” he said, and he flatly refused to give them anything back. “It is best for you to drop all mention of the refugees,” he declared to Oswald.89 Either accept his terms, or keep fighting the war. It was easier, apparently, for two nations to agree on every major issue defining their relationship than it was for one father to forgive betrayal by his son. Franklin’s resistance to compensating loyalists would be reflected in his own last act toward William. In his will, Franklin pointedly left William only the land he owned in Nova Scotia (the premier loyalist haven) and a clutch of books and papers. “The part he acted against me in the late war will account for my leaving him no more of an estate he endeavoured to deprive me of,” explained the embittered father.90

Franklin’s challenge worked. The preliminary articles of peace included only a limp nod in the loyalists’ direction. Article V stated that “Congress shall earnestly recommend it to the legislatures of the respective states to provide for the restitution of all estates, rights, and properties, which have been belonging to real British subjects.” That is, Congress would ask the states nicely to give loyalists their property back—but it was entirely up to the states to act as they saw fit. At Franklin’s insistence, the article was phrased only to extend to those loyalists “who had not borne arms against the said United States,” in a stroke excluding thousands of loyalist military veterans from consideration.91 The phrase “real British subjects” would also later cause friction among loyalists who saw it as setting up an invidious hierarchy among British subjects, instead of presuming them all to be equally “real.”

In late November 1782, as the final draft of the treaty was being drawn up, the fourth American peace commissioner arrived in Paris just in time to introduce one last self-interested clause. Henry Laurens had sailed for Europe two years earlier to negotiate a loan with Holland when his ship was intercepted by the Royal Navy and he was imprisoned in the Tower of London on a charge of treason. He endured fifteen months of confinement in a tiny stone cell, intermittently sick, closely monitored, taunted by guards who played “The Tune of Yankee Doodle . . . I suppose in derision of me.”92 He ultimately secured his release thanks to the lobbying—and bail money—of none other than Richard Oswald, his old friend and associate. Joining his colleagues on the eve of the treaty’s signing, Laurens proposed a further detail to be inserted into the text. Britain, he said, must agree to evacuate “without causing any Destruction or carrying away any Negroes, or other Property of the American Inhabitants.” Oswald, who had traded slaves with Laurens for decades, had no objections, and the phrase went in—with considerable consequences to come for black loyalists.

On November 30, 1782, the five commissioners gathered in Oswald’s suite at the Grand Hotel Muscovite to sign the preliminary articles of peace. Many contemporaries were surprised by Britain’s generosity toward the former colonies—but prognosticators saw things differently. At a gathering at Franklin’s house afterward, a Frenchman taunted the British delegation with the prospect that “the Thirteen United States would form the greatest empire in the world.” “Yes,” Oswald’s secretary proudly replied, “and they will all speak English, every one of ’em.”93 Whatever greatness the future might hold for the United States, language itself ensured that it would share with Britain a connection that no other major foreign power could match. In British eyes, the peace achieved an all-important goal, namely to secure the United States in a British sphere of influence, against its rival France. And there was something more. For if, as many then expected, the United States failed to cohere as a single nation, the treaty put Britain in a good position to pick up the pieces. The months of fighting after Yorktown had shown how surrender alone did not end a war. To those in the know, the generous terms of the treaty hinted that it would take more than this peace to end British ambitions in and around the United States.

With the American agreement in hand, British negotiators promptly concluded peace with France and Spain, swapping territories in a familiar eighteenth-century game of diplomatic poker. France and Britain agreed to return more or less to the status quo ante bellum. Of greater consequence to loyalists, Britain arranged to cede East and West Florida to Spain in exchange for continued possession of Gibraltar. In September 1783, Britain signed the definitive peace treaties with the United States, France, and Spain collectively known as the Peace of Paris. On parchment, the American Revolutionary War was over. But on the ground in North America, the evacuations were far from finished.

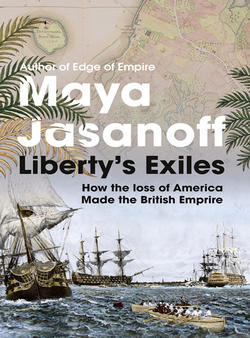

William Faden, The United States of North America with the British and Spanish Territories According to the Treaty of 1783, 1785.