Читать книгу Purple Hearts - Майкл Грант - Страница 12

Оглавление2

RIO RICHLIN—HAMPSHIRE, UK

“Two packs of smokes and the gin,” Rio Richlin says.

The corporal, a chubby young woman with a smiling face and cold eyes, leaning insolently against a jeep, sizes Rio up. “I can get gin anywhere. Give me your knife.”

Rio makes a thin, compressed smile. “I have a sentimental attachment to my koummya,” she says. “Besides, you wouldn’t like it. I haven’t cleaned all the blood from it yet.”

The smile disappears from the corporal’s face. She glances at the knife, then at Rio’s chest, then back at the knife. “Four packs plus the gin.”

“Done. I’ll have it back in twenty-four hours tops.”

Rio Richlin seldom wears her dress uniform, in fact, never recently, but there is one advantage in the remarkably uncomfortable get-up with its multiplicity of buttons, its impossible-to-keep-on cap and its khaki tie: in full dress one wears one’s medals.

The three stripes of the buck sergeant will impress precisely no one in a Britain neck-deep in the soldiers, sailors, coastguardsmen and airmen of a dozen nationalities. But the red, white and blue ribbon, beneath which hangs a pale gold star, is the Silver Star, (despite the baffling color of the actual star) and is given for Gallantry in Action. Quite a few Silver Stars have been handed out, but when Rio received hers it was the first time the medal had been awarded to a female combat soldier. Ever.

The star cuts down considerably on the number of leering, obnoxious, improper suggestions Rio has been on the receiving end of. Mostly you didn’t get the Silver Star unless you’d made a fair number of German and Italian widows and orphans, and that realization causes some male soldiers to . . . well, reconsider making a crude pass at Rio.

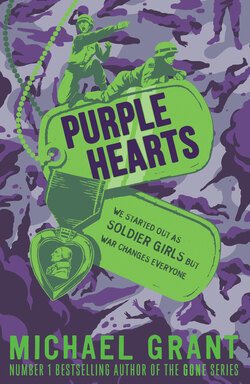

Alongside the Silver Star is a second medal, a purple ribbon above a gold heart, which has within it a lacquered purple valentine, all framing a gold profile of George Washington himself.

This is the Purple Heart, given to soldiers wounded in battle. On the back in raised letters the citation reads For Military Merit, which is a bit silly since to Rio’s mind there’s no great “merit” in getting shot or sliced up by shrapnel. But resting as it does beside her Silver Star, the combination sends a clear message in the language of the US Army: this is the real deal.

This is a combat soldier.

And that separates Buck Sergeant Rio Richlin from ninety percent of the men and women in uniform swelling the trains and roads and villages and village pubs of Britain.

The transaction complete, Rio hops in the jeep and drives away, moving fast because that’s how all the jeep drivers drive, fast, like gangsters trying to outrun the cops in a James Cagney movie.

It is forty-seven miles to the air base where Strand Braxton is based. It should be an hour’s drive at most, but the road through the damp-lovely springtime English countryside is jammed with every manner of military vehicle from jeep to truck to tank. Military Police man crossroads and try to direct traffic, sometimes in loudly profane ways, and at one point Rio is told she cannot take a particular road but must go far out of her way. Here too her medals (plus two packs of smokes and a silk scarf) convince the MP that the restriction somehow does not apply to her.

The slowness of the drive eats up hours of time she doesn’t have, and worse, leaves her free to think. Rio has a lot to think about—the imminent invasion and the role of her squad. It still seems strange to think of it as her squad. The squad, nominally twelve men and women led by a sergeant, in this case Rio, consists of her lifelong friend, Jenou Castain—Corporal Jenou Castain—as well as her long-time companions Luther Geer, Hansu Pang, Cat Preeling, Beebee, whose real name no one even remembered anymore, some replacements that didn’t yet matter, and Jack Stafford.

Jack Stafford with whom she shared a foolish kiss long ago. Jack with whom she had spent a horrible night lying in a muddy minefield, huddling together for warmth. Jack, the Brit who’d ended up in the American army. Devilish, witty, fearless Jack.

Jack who is now her subordinate and about whom she was not to think of in that way. Not that she ever really had, well . . . occasionally. But that whole thing was utterly impossible now. Over. Done with.

Which is one of the reasons she was going to see Strand Braxton, because if Strand and she were . . . well, whatever you called it, engaged, she supposed, then she would have one more mental defense against stray thoughts of Jack.

Stafford, Rio chides herself, not Jack. Private Stafford.

She arrives at the air base to find more MPs, and these are not quite so easily dealt with. So she gives her name at the gate, and Strand’s name, and after a phone call they decide she’s not likely to be a German saboteur or spy, and wave her through.

The airfield is a vast expanse of torn up grass and mud distantly ringed by trees on two sides, farm fields on one side, and the road itself. Rio pulls over to look, taking it in. She can see a handful of low buildings, a stubby control tower with a fitful windsock, a bristling antiaircraft gun emplacement, the usual cluster of jeeps and trucks and low-slung tractors, and beyond them the great behemoth planes, the B-17s. She counts six, but suspects there are more out of view.

She pulls up to the parking area and spots a tall, young officer trotting toward her. He looks serious until he notices that she is watching him and then breaks out a big grin.

Strand Braxton throws his arms around Rio, lifts her off her feet and swings her around. They kiss once, quickly, then a second time more slowly.

Yes, Rio notes, I do still like that.

“Gosh, it’s great to see you!” Strand says. “The MPs called me from the gate and I thought they were pulling my leg.”

“Sorry I didn’t give you any warning, but a pass came up and I grabbed it.”

“How long can you stay?”

“Well, I have temporary possession of a major’s jeep, so I’ve promised to have it back to his driver within twenty-four hours.”

“Twenty-four hours! But . . . but we’re on.”

The phrase confuses Rio for a moment. “You’ve got a mission?”

He nods and for a moment his smile crumbles before being replaced with some effort by a less-convincing smile. “Probably a milk run. We haven’t been briefed yet. Come on, I’ll get you a cup of tea and you can meet some of the boys.”

“I thought you fly-boys spent all your spare time drinking and carousing,” Rio teases as they walk arm in arm, taking exaggeratedly long, synchronized strides.

“I don’t know where that idea got started,” Strand says, shaking his head. “No one would want to be hungover. Or even low on sleep. Now, once you get past the Channel and the Messerschmitts start coming up . . .” He laughs, but the laugh is as off as his smile. “Well, then you might want a drink.”

Rio looks at his profile, but can’t read anything in particular, beyond the fact that Strand looks tired. Tired and older.

I suppose I do too.

“Hey, are you taking me to officer country?” Rio asks, hesitating at the door to what is labeled “Officers’ Dining Club and Dance Emporium.” The sign is in official block letters, but is also obviously not the official army designation. Below it a second, smaller, hand-lettered sign: “God’s Waiting Room.”

Strand waves off her concern. “We don’t stand on ceremony much. And we sure don’t get enough pretty girls dropping by to push one away!”

Inside, Rio finds a long, rectangular room with a grab bag of chairs ranging from stern metal office chairs to plush parlor chairs and a scattering of low tables. The room smells of tea—a habit some flyers have picked up from the RAF, the Royal Air Force—as well as the usual coffee and the inevitable smoke. Perhaps two dozen flyers are present, sprawled or sitting upright, many with books in their hands and attentive expressions on their faces. A radio plays Glenn Miller’s ‘Sunrise Serenade.’

“We just came from briefing,” Strand says apologetically. “We’ll be heading off soon.”

A very pretty redheaded pilot gives Rio a nod. Recognition? Comradeship?

Guilt?

“I know I should have waited till we had a time set, but you know how it is,” Rio says. “Bad timing. But your letter did say as soon as possible.”

“Well, I was hoping we’d have a few days in London,” he says. Addressing the room in a loud voice he says, “Boys, this is Rio, my girl, so watch your language and keep the wolf whistles to yourselves.”

Rio doubts that she is worth a wolf whistle. She hasn’t worn makeup or fingernail polish in a very long time. She’s dressed in a uniform that does not leave a lot of possibilities for showing leg, and her hair is the now-regulation two inches long.

And then there’s her koummya, which she should certainly have left with Jenou. But the koummya, a curved ceremonial-but-quite-functional dagger she’d picked up in the Tunis bazaar, has become something more than just a knife; it has acquired the status of talisman. It is her lucky rabbit’s foot. She knows it’s superstitious, but without it she feels vulnerable. Even in camp, where she shares a tent with three other NCOs, she keeps it by her cot, always within reach.

Many eyes in the room go straight to the koummya, but then they move on, checking out her face and her figure, neither of which Rio thinks likely to please anyone, but smiles break out, and waves and nods.

And one wolf whistle.

“How long do you have?”

Strand glances at a wall clock and says, “If I trust my first officer and crew to handle loading and fueling, I’ve got four hours free.”

Rio’s heart sinks. Four hours ? It’s too long for a chat, too short a time for anything deeper. She has come here to reach a decision. To reach it with Strand, hopefully. To decide what exactly they are to each other.

No promises have been made, no proposal offered or accepted. But somehow Rio has felt that it was there, implied, assumed. An understanding. But she’s not sure that’s how Strand sees it. Maybe what he understands is different from what she thinks.

More importantly, Rio has changed.

When she first enlisted it had almost been a whim. Yes, her big sister Rachel had died fighting the Japanese in the Pacific, and yes, that formed part of her motivation, but when she is honest with herself Rio knows that she really joined because Jenou was joining, and because like Jenou she was bored with life in Gedwell Falls, California. And because she’d felt swept up. Like the great tide of history had risen around her and carried her off, a piece of flotsam in a flood.

She had never meant to be near the front. No one thought when the Supreme Court handed down its decision making women subject to the draft and eligible for enlistment that women and girls would end up in the thick of the action. But the army, with much internal fighting and several high-profile resignations, decided to treat female recruits just like the men. Some of that was male generals hoping to see women fail. Some of it was women (and some men) interested in equality of the sexes. Much of it was just a rigid bureaucracy not accustomed to dividing assignments by gender.

Rio had lied about her age and signed up in the autumn of 1942, at the same time as her . . . what to call it? Friendship? Her friendship with Strand Braxton? Autumn of 1942 was almost two years ago. She’d been an average, barely-seventeen-year-old girl, a girl with homework assignments and chores. Then had come basic training. And a brief sojourn in Britain for more training. Followed by Rio’s first encounter with combat during the fiasco of Kasserine Pass in North Africa.

Since then she had been to Sicily and Italy and been shot at, shelled, strafed and bombed. She had marched many miles, carried many loads, dug many holes. She had used slit trenches and bushes, bathed in her helmet, changed sanitary pads in burning buildings.

Most profoundly she had gone from heart-stopping panic the first time she lined the sights of her M1 up on a human target and taken his life, to becoming a professional combat soldier. A professional killer.

And she had moved from a private, with no responsibility but to obey orders, to a sergeant, with her own squad of eleven soldiers to look after.

Any baby fat she’d ever had was long gone. She was tall, lean and strong, with calloused hands and stubby, broken nails. When she moved it was with quick economy, efficient, wasting not a calorie of energy. And something had happened to her voice: it was still hers, but now it carried undertones that spoke of confidence, control and command.

She had also acquired several unladylike habits. She still smoked less than many, but smoke she did because when it was cold in a foxhole a cigarette was life’s only small pleasure. And she drank on occasion, not usually to excess, but with enough devotion that there was now a flask of whiskey in her pack. When she ate it was like a starved wolf. When she spoke it was with less and less concern for curse words.

And then there was the fact that she had slept with Strand.

Yes.

That fact had never quite been . . . what? Figured out? Adjudicated? Processed?

The next time she’d seen Strand she had been leading a patrol that ended up rescuing a wounded Strand after his plane was shot down over Sicily.

And that too had not been processed.

War was hell on relationships.

“Four hours?” Rio says. “Well, let’s make the most of them.” Only when the words are out of her mouth does it occur to her that he may take this as a suggestion of sex. She blushes, but at the same time, would it be such a terrible way to spend the four hours? It would distract them both from the weightier questions. A pleasant way to avoid . . . well, to avoid the very reason she had come here.

“Listen, there’s a sort of gazebo behind the building, it’s a place where couples sometimes go to be . . . to have privacy.” He winces, obviously concerned that she is misreading his intentions just as she is concerned about him misreading hers.

The gazebo is more of a lean-to, a shelter enclosed on three sides but open to the airfield. Rio sees crew working on the planes, low tractors hauling trailers loaded with bombs, boxes of machine-gun ammunition being handed up through the belly hatches. Hoses crisscross the ground, pulsing with aviation fuel.

They sit side by side on a little bench, pastoral quiet contrasting with the feverish activity on the field.

“You know, Rio, I was quite proud of you when I heard about the Silver Star. Why didn’t you tell me? I had to read about it in Stars and Stripes ! One of the fellows showed it to me.”

“It’s not such an important thing,” Rio says.

“Nonsense, it’s a very important thing. It seems you are rather brave.” He smiles. But again, it’s not quite the right smile.

Rio shakes her head. “You know how it is. Everyone does their job as best they can, and one person gets singled out for a medal.”

“You saved my life,” he says flatly. He holds up a hand to silence her protest. “I won’t deny that I’ve taken some ribbing over that. How I had to be rescued by my girl. How my girl has a Silver Star.”

There is an awkward silence. Rio doesn’t know what to say. Is she supposed to be ashamed of having carried off her mission? She glances at him and tries to read his mood from the set of his jaw. Yes, she realizes with amazement, he does actually seem to resent her, a little at least.

Or am I just imagining things?

“Should I have left you there?” Rio asks.

He shakes his head slowly. “No, sweetheart, of course not. It’s just . . .”

“Just what?”

“Well, it’s hard, that’s all. See, I’ve missed the last two missions because of mechanical problems, all perfectly proper, I was following standing orders. But on top of, well, you, there’s that, and some of the fellows take the joke a bit too far is all.”

“I’m sorry, Strand. But there’s nothing I can do about that.”

“The story in Stars and Stripes even mentioned that I was delirious and singing Christmas carols.”

True enough. When Rio’s patrol had found Strand’s plane, he had been wounded and out of his head. But the detail rankles Strand. His mouth twists at the memory.

“I should think people would find that funny and endearing,” Rio says. She frowns at the sound of her own words. Is this how she speaks? In this diffident, apologetic tone? She has the sense that “endearing” may be the first three syllable word she’s spoken in months. Her sergeant’s vocabulary tends toward words of one syllable, generally either expressed in a low mutter or an irritated shout.

Jenou’s right: I have changed.

“I’m a B-17 pilot,” Strand says heatedly. “I’m not meant to be endearing or funny, Rio. I’m the youngest officer here, even my radioman is older, so, you can imagine.”

“Well, I’m sorry.”

“I never should have let you enlist,” Strand mutters.

“It wasn’t your decision.”

“Oh, believe me, I know that! I let Jenou talk you into this madness. I can’t imagine why they haven’t sent you home to sell war bonds, you’d be a natural.” He looks at her, forces a grin and adds, “Of course, they’d doll you up.”

“They offered,” Rio says.

He stares at her. “What? You mean they offered to send you home? Did you refuse?”

Rio shrugs. “I thought I’d be more useful here looking after my squad.”

That’s not quite the whole truth. She had been tempted to go stateside and had thought especially hard of refusing the promotion to sergeant, until an Army Intelligence sergeant named Rainy Schulterman, one of her fellow medal recipients, had guilted her into it. After painting a word picture of Nazi oppression, Schulterman had talked about green kids from Nebraska landing on French beaches and going up against the Wehrmacht.

“They’ll need people who know how to fight and how to keep guys from getting killed. What do we call those people, Richlin? What do we call those people, Rio Richlin from Cow Paddy or Bugtussle or wherever the hell you’re from?”

Schulterman had supplied her own answer.

“Honey, I hate to tell you, but they call those people sergeants.”

Now here I am, Rio thinks, Sergeant Rio Richlin, sitting awkwardly with her resentful . . . boyfriend? Beau?

Fiancé?

Strand looks down and shakes his head. “Do you have any idea how many of the flyers here would go home tomorrow if they could? You don’t . . . I mean, sure, I know you’ve been in the fighting, but you can’t imagine what it’s like for us.”

“You’re right,” Rio snaps, turning more sergeantly by degrees. “I don’t know what it’s like to come back at the end of a patrol to find a comfy bed and a hot shower.”

Strand waves a hand dismissively. “I didn’t mean it that way. It’s just . . . we lose men on almost every mission. You remember Lefty? You met him. Me 109, you know, Kraut fighter plane, caught him over Germany. Six of his crew were killed or injured in the first pass, two engines out. Lefty shot through the cheek but still trying to get his bird home. He went down in the Channel. Three of his crew bailed out and were picked up, but not Lefty.”

Rio is on the point of retorting that she knows quite well what an Me 109 is, having been strafed more than once, and with a list of the deaths of her own friends, but that’s nuts; surely, this is not some competition to see who is having the worst war?

“I’m sorry to hear about Lefty.”

“You’ll be sorry to hear about me soon,” he says with surprising savagery. He clasps his hands together and Rio sees that he is trembling. “Sorry. I didn’t mean . . . Never mind me. I’m usually in a foul mood before a mission.”

“There’s nothing wrong in being afraid,” Rio says. “In fact—”

“Who says I’m afraid?” he snaps.

“Everyone is afraid, Strand.”

He snorts derisively. “Everyone but you, Rio. Look at you. What would your mother have to say about that wicked knife? Have you sent them a copy of your citation? You charged a squad of Wehrmacht by yourself !” His voice rises toward shrill. “You blew up my old plane and saved the Norden bomb sight and came near to being blown up yourself. My God, Rio, you’ve become the very model for all the rabble-rousers who support this whole crazy notion!”

“Crazy notion?” The strange thing is that as she speaks those two words, she recognizes the silky menace in her tone. It’s pure Mackie, her sergeant during basic training. If things were not so tense she might laugh at the comparison. Mackie could terrify a recruit just by the way she walked.

“Yes!” Strand says. “Yes! I’ll say it: crazy notion. Just because you’ve become a good soldier does not mean that it makes any sense for women to be in this war!”

“You have women pilots, women air crew. I saw a rather pretty redhead . . .”

“Sally? At least she would have the sense to go home if the opportunity came up. She agrees with me, with, well, everyone really. Women are meant to be the gentler sex. That’s the grand design. Women aren’t meant to . . . to . . .”

“Kill Germans?” The same Mackie menace.

“My God, Rio, listen to yourself. You positively sound as if you are threatening me!”

Rio jumps to her feet. “You’re shouting at me, Strand.”

His look is cold. His hands remain clasped, squeezing to stop the trembling. “You’ve made me a laughing stock. Fellows ask me when we’re married whether I’ll be doing the cooking and cleaning.”

When we are married?

“I don’t recall agreeing to marry you. For that matter, I don’t recall you asking.”

He frowns, puzzled. “It’s understood, surely? You gave yourself to me; did you think I wouldn’t do the right thing?”

“So . . . you would marry me from a sense of obligation? Duty?”

“No, no, of course I didn’t mean that.” He retreats quickly, but the resentment still comes through. “I love you. Of course I love you. I just sometimes wish . . .” He hangs his head. “I just wish sometimes you were still the sweet, innocent young beauty I gave a ride to in my uncle’s old Jenny.”

“That was a long time ago,” Rio says. Her voice gentles at the memory. Strand’s uncle had a Jenny, a Curtiss JN-4 biplane he used as a crop duster. Strand had already known how to fly and he took her up over Gedwell Falls in what was the most thrilling moment of her life. Up till then.

She had squeezed into a single cockpit with Strand, leaning back against him, feeling for the first time what a man’s body felt like.

She wouldn’t, couldn’t lie to herself: many times she had wished she was back there, back then, being that version of herself. It wasn’t her lost virginal naiveté that made her nostalgic, but rather the feeling that she had changed so much there was no longer any going back. The male soldiers would return home some day and would be seen as more than they had been, stronger, braver. But the women? No one knew how women who had been to war would be received.

Strand pictured her in an apron. So had she, once. And who knew, maybe she would see herself that way again.

Mrs. Strand Braxton?

Mommy?

Baking cupcakes for the PTA fundraiser? Wearing a nice summer dress to church? Excusing herself from men’s conversation after dinner to go to the parlor with the other ladies to talk about hairstyles and movie stars and brag about little Strand Jr.’s A-plus in algebra?

That had been her mother’s life, a life that had once been inevitable, but now felt very, very far away.

But even as she drifts toward those melancholy thoughts, a part of her mind is elsewhere, wondering if she could transfer Rudy J. Chester out of her squad; wondering if Lupé was as tough as she acted; wondering whether Geer is working them hard in her absence.

The silence stretches on too long.

“I guess we won’t figure out what’s what until it’s all over,” she says.

Strand snorts derisively. “There probably won’t be an after, Rio. The Old Man says the Luftwaffe isn’t what it used to be, but just about every mission a bird goes down. It’s a matter of mathematics. Every mission . . . a Kraut fighter, ack-ack, mechanical breakdowns . . .”

“You can’t think about that,” Rio says. “You just have to focus on your objective.” She very nearly pronounces it OB-jective, the way Sergeant Cole always did.

Suddenly Strand stands too. He turns cold eyes on Rio. “No, that’s you, Rio. Not me. Me, I think about it. I’m not a machine.” He makes an effort to end things pleasantly. “Speaking of machines, I need to go and see to mine. It’s good to see you, Rio.”

“Yes. Take care of yourself, Strand. Goodbye.”

That last word is to his back.