Читать книгу Messenger of Fear - Майкл Грант - Страница 7

2

Оглавление“We have to help her.”

“She is past help,” the boy in black said.

“She’s standing, she’s . . . Can you hear me?” I addressed this to Samantha, knowing how foolish it was, knowing that my words would fall into the inconceivably vast chasm that separates the living and the dead.

No flicker of recognition in those brown eyes, no sudden cock of the head. I was inaudible and invisible to her.

Then she began to move, to walk. But backward. Away from us but backward, not awkward but with normal grace. As though she had always walked backward. Backward across what was now a suburban street. A car came around the corner, not fast, the driver seeming to check for addresses as he drove. If he saw Samantha, he gave no sign of it. I was sure, too, that he did not see me or the boy in black.

The car moved forward normally. Across the street a dog raced along its enclosure, moving forward as well, seeing the car but not us. Only Samantha was in rewind, only she moved backward to the sidewalk, to the flagstone-paved path, to a front door that opened for her. Now it was opened by her but all in reverse. It was a disturbing effect, part of what I was now sure had to be a strangely elaborate dream. Dreams could play with cause and effect. Dreams could show you bullet wounds and staring girls and people walking backward. Dreams could move you from black-hearted un-church to sunlit suburbia without effort.

“A dream,” I whispered. I looked again at the boy. He had heard me, I was sure of that, but his expression was grim, focused on Samantha.

The door of the house closed and should have blocked her from our view, but we were now inside that house, though we had passed through no door. We were in a hallway, at the foot of steps leading upward.

There were framed photos on the wall beside the steps: a family, parents, a little boy and Samantha. And other pictures that must have been grandparents and aunts and cousins. I saw them all as, without thinking about it, I began to ascend those steps. Even as Samantha walked backward up them.

She disappeared around the corner at the top, but the boy in black and I arrived at her room before she did. By what means we came there, I could not say, except that that’s how dreams are.

I felt sick in my stomach, the nausea of dread, because now I was sure that I knew what terrible event I would soon witness.

And oh, God in heaven, if there is one, oh, God, it was happening, happening before my eyes. Samantha sat on the edge of her bed. The gun was in her lap. Tears flowed, sobs wracked her, her shoulders heaved as if something inside her was trying to escape, as if life itself wanted to force her to her feet, force her to leave this place, this room, that gun.

“No,” I said.

She was no longer moving backward.

“No,” I said again.

She raised the gun to her mouth. Put the barrel in her mouth. Grimaced at the taste of steel and oil. But she couldn’t turn her wrist far enough to reach the trigger and yet keep the barrel resolutely pointed toward the roof of her mouth.

She pulled it out.

She sobbed again and spoke a small whimper, a sound so terrible, so hopeless, and then she placed the barrel against the side of her head, which now no longer showed the wound, the wound that was coming if she didn’t—

B ANG!

The noise was so much louder than in movies. I felt as if I’d been struck physically. I felt that sound in my bones and my teeth, in my heart.

Samantha’s head jerked.

Her hand fell away, limp and blood-spattered.

Blood sprayed from the hole for a moment, then slowed to an insidious, vile pulsation.

She remained seated for a terribly long time as the gun fell and the blood poured and then, at last, she fell onto her side, smeared red over the pastel floral print of her comforter, and rolled to the floor, a heap on the carpet.

The gunshot rang in my ears. On and on.

“I don’t like this dream,” I said, gritting my teeth, shaking my head, fighting the panic that rose in me.

The boy in black said nothing. He just looked, and when I turned to him for explanation, I saw a grim mien, anger, disgust. Simmering rage. His pale lips trembled. A muscle in his jaw twitched.

He crossed abruptly—his first sudden movement—to the desk in the corner of the room. There was a laptop computer open to Facebook. There were schoolbooks, a notebook, a Disney World cup holding pencils, a dozen colorful erasers in various shapes, a tube of acne medicine, a Valentine’s card curled with age, a photograph of Samantha and two other girls at a beach, laughing.

There was a piece of paper, held down at the four corners by tiny glass figures of fancifully colored ponies. The paper had been torn from the notebook.

The boy in black looked down at the paper and said nothing. He looked at it for far longer than it could have taken to read the few words written there in blue ink. I knew, for I, too, read the words.

I love you all. I am so sorry. But I can’t anymore.

—Sam

I found that I could not look up from the words. I felt that if I looked away, I must look at the dead girl, and I didn’t want to see her. She had still lived when she had written these words.

Then I realized that he was looking at me.

“Why is this happening?” I asked him.

He touched the note reverently with one finger.

“Why am I here?” I asked with sudden vehemence.

“The same reason we are all here,” the boy said. “To learn.”

But I had lost patience with cryptic answers. “Hey. Enough. If this is a dream, then I don’t have to put up with you!”

“Mara,” he said, though I had never told him my name. “This is not a dream.”

“Then what is it, huh?” My voice was ragged. I was sick through and through, sick with what I had just witnessed, sick with what I feared about myself. “What is it and what are you?”

“I am . . .” he began, then hesitated, considered, and again showed that slight lessening in the grim lines of his face. “I am the messenger.”

“Messenger? What’s your message, showing me this poor dead girl? I never wanted to see that. I don’t want it in my head. Is that your message? Showing me this?”

“My message?” He seemed almost surprised by the question. “My message? My message is that a price must be paid. A price paid with terror.”

I reached to grab him angrily, but he moved easily out of range. I had wanted to grab him by the throat, though I had instead reached for his arm. It was not that I blamed him for what I was now enduring, it was rather that I simply needed to hurt someone, something, because of what I had seen, and what I had felt since waking to find myself in the mist. It was like an acid inside of me, churning and burning me from the inside.

I wanted to kick something, to shout, to throw things, to scream and then to cry.

To save that poor girl.

To wipe the memory from my mind.

“You’re the messenger?” I asked in a shrill, nasty, mocking voice. “And your message is to be afraid?”

He was unmoved by my emotion . . . No, that’s not quite right. It was more accurate to say that he was not taken aback. He was not unmoved, he was . . . pleased. Reassured?

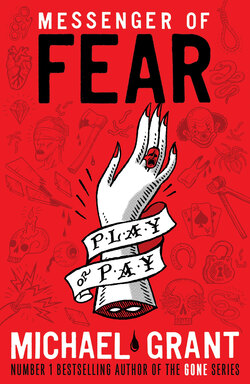

“Yes, Mara,” he said with a sense of finality, as though now we could begin to understand each other, though I yet understood nothing. “I am the messenger. The Messenger of Fear.”

It would be a long time before I came to know him by any other name.

Calmer now, having released some of my boiling anger and worry, I turned my unwilling eyes back to Samantha Early. Her life’s blood was running out, soaking into the carpet.

“Why did she do it?” I asked.

“We will see,” Messenger said.