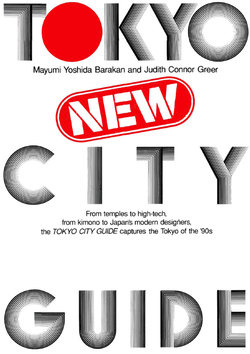

Читать книгу Tokyo New City Guide - Mayumi Yoshida Barakan - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

June 1996

Fifteen years ago, when I first came to Japan from America, I didn't buy a guidebook to the city. The books available directed the tourist to bus tours, expensive imported designer boutiques in Ginza, to ancient nightclubs and cabarets. It was just intuition at the time, but I knew there must be more than that going on in Tokyo, and I decided to find out what it was.

Over the years Mayumi and I have guided hundreds of friends through the city. We became experts at drawing maps and running off copied handouts on where to go, what to do, and where to find what. It was always fun, always great to see people get as excited about the city as we were. Still, we often wished that there was a single volume, collecting all the information, that we could give to visitors. The book should have been published long ago, and when no one else did it, we decided to do it ourselves.

In the past few years Tokyo has received more good PR overseas than any other city in the world. More and more people are coming to the city, most of them with different reasons and expectations from those that people came with ten or even five years ago. For some, the city is disappointingly westernized; for others, it's a super-technopolis of the future. For yet others it's simply frustrating. But few people fail to be intrigued, if not captivated, by the curious combination of new technology, internationalism, traditional behavior and aesthetics, and the cross-cultural kitsch that make up Tokyo's special brand of urban life.

The city casts its spell over even the most adamantly unhappy of its foreign residents. Conversations here turn with an almost predictable frequency to Japan and the Japanese. Much of the talk consists of complaints, accusations, stories about silly Mr. Suzuki, or games of one-upmanship as to who has read the most hysterical, the most bizarre, or the most obscene misprinted English phrase of the day. But whether arising from love or hate, the fascination never dies.

The repertoire of complaints is fairly standardized: the ugliness of the city; people rudely pushing and shoving their way through crowds; the noise pollution; the difficulty of getting around with no consistent system of addresses or street names; the constant pointing and staring at foreigners and the audible "gaijin da!" ("It's a foreigner!"); the pervasive belief that foreigners can't learn the impossible Japanese language. But most vehemently criticized is the general sense of regimentation and the overall lack of individuality in the people—the inability to do anything that doesn't go by the rules or isn't decided after lengthy discussion with the "group."

The criticisms are at least partially justified, the frustrations undeniable. You can go into a coffee shop and order a ham and cheese sandwich, hold the ham (or even just the mustard), and it provokes a major crisis. If you're feeling assertive, you'll get angry, wondering why something so simple can't be done. But that's how things work here so eat your sandwich ham and all, quietly take it off yourself, or leave Japan.

The aggressive individuality most foreigners were raised to believe in doesn't figure in the Japanese scheme of things. The Japanese do not believe in individuality, but in the concept of a group where every single person has his place, duties, and responsibilities. This one basic difference leads to more misunderstanding and frustration than any of the multitude of other cultural differences. Individualism is great and makes for a vibrant and actively creative society. But it's not the only way to organize lifeS, and certainly not the Japanese way. To their credit, the Japanese have managed to work out a system that keeps most of the population healthy, happy, and prosperous—if lacking in individuals. For skeptics it's worth noting that the state of Japan is analogous to a hypothetical situation where half the population of the United States would be squeezed into Southern California. All those American individuals would probably end up killing each other off within the week. You pay one way or the other.

The bad parts of the city are the most blatantly obvious, while the good parts are often found in the easily overlooked small things—the careful wrapping of the most humble purchase, the hot oshibori towel before a meal, the safety, the back streets swept spotlessly clean by the local residents—all of which are just day-to-day manifestations of the general Japanese attitude toward life. It may sound simplistic, but for us, the good parts of the city are a more than equal trade-off for the bad.

We both came to the city as temporary residents. Mayumi arrived as a college student in 1977 from Sapporo, a city in northern Japan. Her reactions were at first similar to those of any tourist and she often thought of leaving. But after spending a year in London, she returned with a new interest in things Japanese and an objective appreciation for Tokyo.

I came from Seattle, a provincial city on the West Coast of America. Tokyo was to be the first stop on a trip around the world. I stayed and learned the language. Curiosity kept me here as three months turned into four years, and I'm still curious.

We both have a great time in Tokyo. We like the technopolitan city that's built on an unshakably Japanese foundation. Tokyo lacks the glamour and sophistication of New York and Paris, but the combination of new and old, the ceaseless input of new cultural variables from around the world, the friction between what gets accepted and what doesn't, give the city an energy-the excitement of a contemporary urban culture constantly in the process of creation.

The Tokyo City Guide has been out of print since about 1990 and the question of updating or not updating has cast its shadow over our lives for about that much time. We were not really sure we wanted to take it on again, and more-or-Iess hoped that someone who had the spirit we had in 1984 would come out with something new and better. Every time we went to a party and were asked when the new edition was coming out-we cringed. After years of cringing and a few false starts, it finally happened.

In some ways, the revision has resulted in a more conservative book than its predecessors. This has been a hard thing to accept, but aside from the fact that we are no longer the wild and free young women we were in 1984, experience has taught us that too many of the new places go under and that no one wants to search out a place that maybe was interesting three years ago, but no longer even exists.

For better or for worse, this new version is perhaps more personal than our first edition. With so many new and good clubs, restaurants, and shops-we have had to make our selections based on personal choice. And, predictably, we have included a section on children which was missing from our earlier book and our art and architecture sections have grown.

Tokyo has changed since the first edition of the Tokyo City Guide was released in 1984, and so have our lives. With two children each, we no longer find ourselves at bars, discos, and restaurants after midnight. In our mid- to late thirties, we no longer shop on the back streets of Harajuku. For better or for worse, we experience the city in a different way.

When people hear I've been in Tokyo for more than a decade, the almost inevitable response is "So, you must love it!" I never quite know what to say. In some ways Yes, in others No. Mayumi feels the same. But I suspect that someday, when we both live in some other city, in some other part of the world, we'll both remember Tokyo as the city where we spent the most interesting and exciting years of our lives.